Former U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins’s new book lists 86 honorees on its dedication page. They have such names as Angus, Belle, Colonel, Dapples, Elektra, Lefty, Ollie, Peanut, Scrambler, Trigger and Willie. Given that all are dogs, it’s a bit surprising that their number includes no Rovers or Fidos—but it appears that those clichéd monikers fell out of favor decades ago.

Still, to paraphrase another famous poet, dogs by any other name still smell, well, as much like dogs as they ever did. But, at a time when humans can barely stand the sight of one another, they remain man’s best friend and his only reliable source of unconditional love and loyalty.

So it was only a matter of time before America’s favorite poet devoted an entire volume of verse to America’s favorite four-legged mammal. Dog Show (Random House, 2025) celebrates the bond between us and our furry friends. And it does so in a way that makes us both chuckle and choke up—sometimes in the same couplet—without ever succumbing to slapstick or schmaltz.

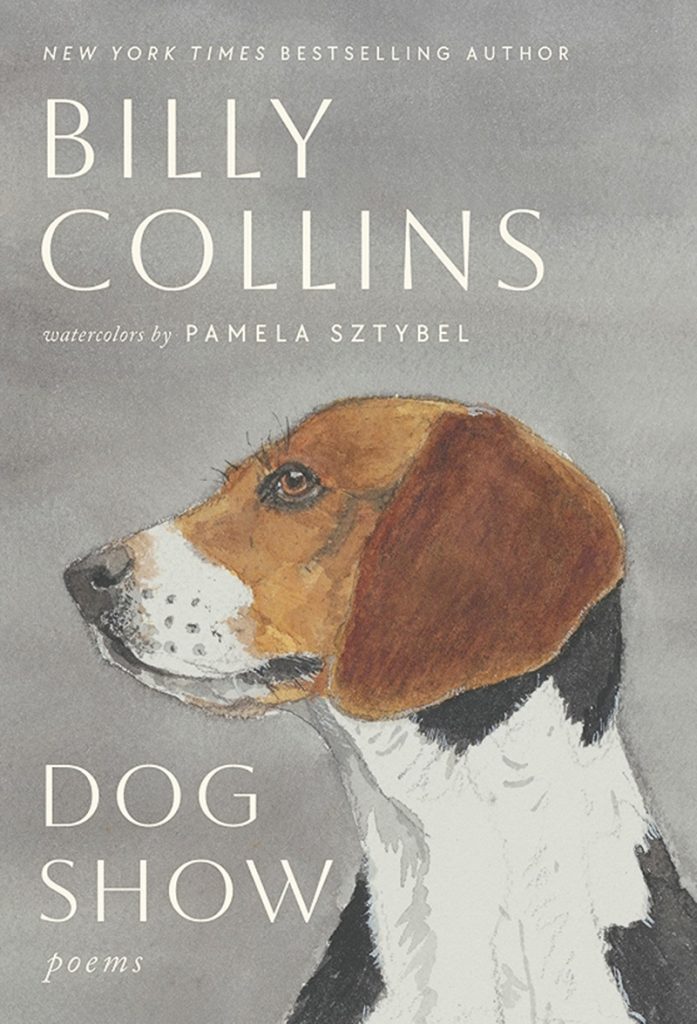

Not surprisingly, the compact volume—an ideal stocking-stuffer that encompasses just 25 poems, some of them familiar favorites—trotted to the top of several national bestseller lists prior to Christmas. The poems, as an added bonus, are accompanied by vivid watercolor portraits of dogs by renowned painter and printmaker Pamela Sztybel.

Although Collins’s books are always popular and well-reviewed, Dog Show got a nod from none other than Oprah Winfrey, who called it “a sweet gift for dog lovers” and added it to her annual list of “Favorite Things” on the website Oprah Daily. (Works by authors ranging from Toni Morrison to John Steinbeck have benefitted from “The Oprah Effect.”)

Oprah’s instincts were likewise spot-on about Dog Show. Indeed, anyone who has ever loved a dog (and who has been loved by a dog in return) will enjoy this collection because it manages to tug the heartstrings without losing its wit and whimsy. (That description, it should be noted, is applicable to any collection by Collins.)

For example, “Another Reason I Don’t Keep a Gun in the House” finds the poet increasingly annoyed by a neighbor’s barking dog. He tries, and fails, to mask the yapping by closing the windows and playing a recorded Beethoven symphony with the stereo’s volume amped up to a proverbial 11.

But the dog persists even as the record ends, “his eyes fixed on the conductor who is / entreating him with his baton / while the other musicians listen in respectful silence / to the famous barking dog solo, / that endless coda that first established / Beethoven as an innovative genius.”

In “The Revenant,” Collins uses his poetic powers to channel a dog who has been euthanized—a situation in which, one would think, pathos would be unavoidable and humor would be unthinkable. Yet, the poem’s words manage to convey, from the departed dog’s point of view, both regret and revenge.

From the afterlife (where dogs write poetry and cats write prose), the erstwhile pet’s emboldened spirit reveals to his former owner that “I never liked you—not one bit.” He then proceeds to innumerate the reasons why—adding: “When I licked your face, / I thought of biting off your nose. / When I watched you toweling yourself dry, / I wanted to leap and unman you with a snap.”

In “Trying to Write a Dog Poem with Two Cats in the House,” a pair of felines make a cameo appearance. Clearly under the shared assumption that Collins is writing yet another dog poem “rather than one about the two of them,” they stare at him in silence as he scribbles. However, as we soon learn, “they are actually / featured here, / an irony which is all / I have to compete / with their ceaseless gaze.”

Collins being Collins, poignance is also prominent in Dog Show. Oprah’s favorite poem in the collection (and my favorite as well) is “A Dog on His Master,” in which a perceptive pooch comes to realize that he is aging more rapidly than his human and that one day, inevitably, there will be no more walks in the woods.

After he is gone, the dog muses, if his relatively fur-free companion recalls these precious times, “it would be the sweetest / shadow I have ever cast on snow or grass.” OK, Billy, you got me (and, apparently, also Oprah) with those heartrending lines. Our dogs, if only they understood the concept of mortality and could write poetry, would undoubtedly express precisely that sentiment.

Indeed, several (or more than several) selections may make you misty-eyed. In “Good News,” a dog’s master learns that his pet doesn’t have cancer, as had been expected, and marvels at how, upon hearing this welcome report, “everything took on a different look / and appeared to be more itself than it usually is.”

The relieved master, while preparing ratatouille in his kitchen, even begins to admire the assorted utensils around him and comments on how perfectly formed a cheese-grater is “to grate cheese, just as you, with your long smile / and your smooth brown and white coat, / are perfectly designed to be the dog you perfectly are.”

Collins’s eclectic collections typically run the gamut and eschew overarching themes—which means that every turn of the page brings a new adventure. Dog Show, though, focuses his attention on a specific topic. A less deft poet might find it difficult, under those circumstances, to avoid repetition.

But Collins comes at canines (and their bond with people) from many angles. His poems are about old dogs, wet dogs, silly dogs, costumed dogs, working dogs, romping dogs and drinking dogs who hang out in pubs. (You’ve seen the paintings.) No two poems are alike and many take unexpected twists and turns.

Poetry books are for reading, of course. But, in any review of Dog Show, it would constitute critical malpractice not to mention Sztybel’s watercolors and the wisdom of the book’s graphic designer in using them discretely and effectively.

The left-hand pages preceding each poem display portraits of unnamed dogs—some of them adorably scruffy mutts—with their expressive faces backed by solid colors that perhaps reflect their personalities. The illustrations are small and centered on the page, which gives them more punch and lets them complement, not distract from, the airy pages of poetry.

Collins, a New Yorker, has since 2008 lived in Winter Park. Among his accolades are the Mark Twain Prize for Humor in Poetry as well as fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. In 1992, he was chosen by the New York Public Library to serve as “Literary Lion.”

In 2017, Collins—who is married to Suzannah Gail Collins, a former attorney who also writes poetry—was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters, an honor society of the country’s 250 leading architects, painters, composers and writers.