Folks are enamored with opera in Winter Park. So much so that the grassroots efforts of local residents were pivotal in the launch of a thriving new company, Opera Orlando, following the ignominious collapse of its predecessor company, Orlando Opera. (Yes, the names are confusing.)

Opera Orlando—a solid success in its landmark 10th season—has overcome the overwrought backstory that describes the genre’s soaring soprano highs and baffling basso profundo lows in Central Florida.

“Winter Park has been absolutely crucial to our success,” says Gabriel Preisser, general director of Opera Orlando. “We have programs specifically for Winter Park as a way of thanking the residents for their support. We might not be here without them.”

Locals are accustomed to the opera’s Summer Concert Series, which began in 2022 at the University Club of Winter Park. During the intimate event, attendees enjoy a diverse selection of songs, arias and duets from artists to be featured in the upcoming season along with pre- and post-show receptions.

One such program will be a reprise of The Secret River—a commissioned work based on a children’s book by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings—at Mead Botanical Garden’s Grove Amphitheater on Friday and Saturday, March 6 and 7, with both performances at 7:30 p.m. (See page 42.) Here’s how it all came to be, with no intermissions.

Let’s start by meeting Preisser, an Apopka native who occupied two seemingly disparate planets in the stratified universe of public education. At West Orange High School—where his dad was principal—the teenager was a football player who, while wearing his pads, would sing the national anthem prior to games. And he would just as eagerly participate in the school’s musical productions—an extracurricular activity not often associated with jocks.

But this seeming incongruity made perfect sense in the Preisser household because patriarch Gary’s storied career also included stints as a football coach at Apopka, Bishop Moore, Dr. Phillips and Edgewater high schools. Matriarch Gerry, however—who had charge of the couple’s five boys and one girl—insisted that all the kids take piano lessons and sing in church.

“Singing came naturally to me,” says Preisser, who was an all-county

offensive lineman. “But I always thought I would go to college at Florida State and walk on and play football. Luckily, I got a full ride for the music program instead and didn’t get killed.”

Lucky, indeed, for both Preisser and for opera fans in Central Florida. Today, Opera Orlando has reached new heights under Preisser and his older brother Grant, who was previously the company’s creative director and is now its artistic director. (The sympatico siblings are often mistaken for one another, which they accept with good humor.)

FLUCTUATING FORTUNES

Reaching this point has had its share of grandiose drama. Opera as a genre has traveled a long and winding road in Orlando that began in 1958 with the Junior League of Orlando’s Gala Evening of Opera at the Orlando Municipal Auditorium (later the Bob Carr Theater).

For that auspicious event, four stars of New York’s Metropolitan Opera—soprano Lisa Della Casa, mezzo-soprano Elana Nikoliadi, tenor Richard Tucker and baritone Robert Merrill—appeared with the Florida Symphony Orchestra in a concert that the Orlando Sentinel called “one of the biggest musical events in the history of Central Florida.”

Tucker returned in 1963 to star in a fully staged production of La Bohème. Then, following a lull, the Junior League passed the proverbial baton to the new Orlando Opera Guild of the Florida Symphony Orchestra.

In 1974, the guild presented a then-unknown Jessye Norman singing the lead in Aida. It was considered groundbreaking at the time to showcase an operatic performance by an African American. It seemed, after such a string of notable successes, that there really was an audience—and a sophisticated one, at that—for opera in Central Florida.

So, in 1990, Orlando Opera, now a separate nonprofit, became a professional company for the first time. Under Robert Swedberg, general director, it staged some 80 productions, concerts and recitals over a span of 17 years and engaged still more marquee names—including Cecilia

Bartoli, Placido Domingo, Jerry Hadley, Same Ramey and Denyce Graves.

Swedberg resigned abruptly in 2007, but Orlando Opera nonetheless celebrated its 50th anniversary with a fully staged version of Don Giovanni, which was reset in New Orleans and starred Peter Edelman and Inna Dukach. Yet, all was not well. During the Great Recession of 2008—which strangled fundraising and slowed ticket sales—the company’s structural weaknesses were laid bare.

After operating at a six-figure deficit for years, Orlando Opera suspended operations in 2009. To fill the void, the Orlando Philharmonic Orchestra (which was formed in 1993 following the dissolution of the Florida Symphony Orchestra) stepped up and began to offer semistaged versions of operas as part of its regular season in the Bob Carr Theater.

First up was Carmen and Porgy and Bess—with free tickets for those who had paid for Orlando Opera’s doomed 2009-2010 season—followed by La Bohème in 2011 and Rigoletto in 2012. “We can’t afford to lose a single person in this community who’s interested in the arts,” said Margot Knight, then president of United Arts of Central Florida, to the Orlando Sentinel.

The Phil’s efforts, although appreciated and well-reviewed, were really rarified concerts, not full-fledged, over-the-top operas. Considering recent history, however, no one was eager to invest in extravaganzas. As the 18th-century French dramatist Molière put it: “Of all the noises known to man, opera is the most expensive.”

CAREFUL COMEBACK

The best way to come back, boosters believed, was to start small and rebuild an audience for opera in its intended form. So Florida Opera Theatre, the predecessor of Orlando Opera (and later Opera Orlando), was organized within months of the prior company’s collapse by several dozen determined (and undaunted) volunteers whose passion for the art compensated for their inexperience.

Orlando resident Ann Fox, president of the Opera Guild when Orlando Opera disbanded, became Florida Opera Theatre’s first president, and helmed it though an organizational period that included applying for and receiving nonprofit status. After her term was complete, Fox stepped aside and was followed by Maitland resident Judy Lee, who would go on to serve five terms.

“We didn’t do any full operas for several years,” says Lee, whose group initially helped to support opera concerts from the Phil. “We couldn’t afford operas. And because of what had happened [with Orlando Opera], we were very careful. We knew that the first time we couldn’t pay a bill, we were done.”

Still, the volunteer-run Florida Opera Theatre began to gain trust and gather momentum. When the company decided that it was ready to launch fully staged productions, members foraged through their garages and closets for costumes and stage props. They also dipped into their personal bank accounts to hire singers, directors and accompanists—most of whom agreed to work for less than their accustomed fees on behalf of the cause.

And because the company couldn’t afford to rent theaters for every production, members also had to scout out inexpensive—and often ingenious—locations. In fact, its first full-scale opera, Menotti’s The Medium, which featured Vero Beach-based soprano Susan Neves, was performed in December 2011 at the Winter Park home of Steve and Kathy Miller.

(Steve Miller, cofounder of Sawtek Inc., a manufacturer of custom-designed electronic components, died in 2025. Kathy Miller is a classically trained vocalist who has sung in the chorus for several productions by Orlando Opera and remains a major supporter of Opera Orlando.)

Subsequently, the upstart outfit presented The Telephone, a one-act comic opera by Gian Carlo Menotti, at the Germaine Marvel Building near the Maitland Art Center and (appropriately) its adjacent Telephone Museum. The opera was paired with A Musical Revue of Ringing Proportions, in which several cast members performed a selection of arias.

An opera-singing troupe also startled a few lounge lizards and drew double-takes from moviegoers by creating a pop-up, open-air concert at Eden Bar outside Enzian, the art-house cinema in Maitland. (They sang—what else?—“Drink, Drink, Drink” from The Student Prince.)

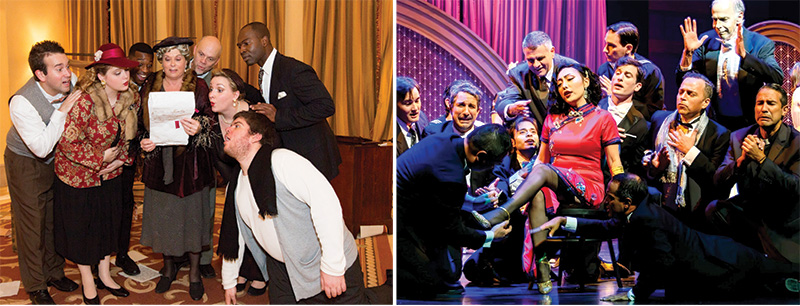

In March 2015, when it came time to debut in the just-completed Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts, the company presented Mozart’s comic opera Così Fan Tutte in the cozy confines of the 300-seat Alexis & Jim Pugh Theater with a chamber orchestra of musicians from the Phil.

After years of performances in unusual spaces, Lee considered the well-received, two-show stand in a real theater to be a coming-out party. “I won’t say none of us knew anything about running an opera,” says Lee. “We had some board members from the previous company who were knowledgeable. But I will say none of us were music majors.”

OPERATIC ENCORE

Who, then, could take this grassroots effort to the next level? Well, as fate would have it, Preisser—the football player-turned-performer—had earned not a concussion (or perhaps worse) but a degree in vocal performance and commercial music from FSU and a master’s degree in music from the University of Houston.

Over the course of his career in opera and musical theater, the charismatic baritone with leading-man looks had notched more than 40 roles—ranging from the title part in Sweeney Todd to Professor Harold Hill in The Music Man—with companies that included, among many others, Helena Symphony, Colorado Symphony, Minnesota Opera and Opera Philadelphia.

He had married his high school sweetheart, Christina, a nurse, who traveled to gigs with him for the first several years before they decided to begin a family and chose to settle back home in Orlando. (The Preissers have two children: Grayson, 11, and Cora, 8.)

Preisser had been hired by Florida Opera Theatre several times as a performer and attended board meetings as an adviser. Perhaps, he recalls jokingly, “I spoke up too much.” Whatever the case, he was soon named executive and artistic director (now general director).

Perfect! A permanent opera job that required no accumulation of frequent flyer miles. Immediately, Preisser recommended rebranding the company as Opera Orlando, a change that was announced in January 2016. Brother Grant, who also attended FSU and majored in voice, joined the newly energized company in 2017 and brought with him skills that both mirrored and complemented those of his brother.

Grant’s impressive resumé includes a master’s degree (one of three advanced degrees) in interior design as well as various executive positions at the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD), including helping to open and serving as dean of the college’s campus in Hong Kong. He has also been a performer, a director, and a sought-after expert in technical theater and production design.

The rest, of course, is history still in the making. Today, with a $3.1 million annual budget, Opera Orlando has a three-show Opera on the MainStage series that typically draws audiences of 1,000 or more per performance to Steinmetz Hall at Dr. Phillips Center. (This season will conclude with a separately ticketed “season extra” at Steinmetz Hall—a one-night-only concert called A Decade of Divas—in May.)

It also presents a three-concert Summer Series at the University Club in Winter Park, on-site operas at unexpected locations, a touring opera in schools and community venues, and multiple special events and educational programs throughout the season. Last year, such programs reached 100,000 people for the first time in the company’s history.

Best of all, Opera Orlando operates in the black. With an eye toward remaining fiscally solid, an endowment fund has been established with a $1 million gift from philanthropist and opera-lover Helen Hall Leon. That gift served as a catalyst for other major contributions, bequests and pledges to the fund, which now totals more than $3 million with a goal of reaching $10 million.

And the company has moved to a larger space in southwest Orlando, thanks in large part to a $125,000 grant from Edyth Bush Charitable Foundation that will support expansion of the scene shop plus the addition of a full-time marketing director.

“Opera is just musical theater on steroids,” says Preisser on the company’s expansive (and sometimes playful) approach to a genre that some still view as stuffy. “We don’t do museum opera.”

FIND A SECRET RIVER AT MEAD GARDEN

A young girl’s ingenuity is tested in a magical musical steeped in Old Florida.

An opera based on a book by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings? Most of us know of Rawlings through her stories about backwoods Florida in the 1930s, among them such classics as Cross Creek and The Yearling. But The Secret River, the author’s only children’s book, remains perhaps her least-known work.

The book’s whimsical musical adaptation, which was commissioned by Opera Orlando, debuted in 2021 in the Alexis & Jim Pugh Theater at Dr. Phillips Center. Audiences were so enchanted that the company is bringing the show back for an encore on Friday and Saturday, March 6 and 7. Both performances will be at 7:30 p.m.

This time, though, the setting will be bucolic Mead Botanical Garden’s Grove Amphitheater. Yes, the performance will be outdoors. And considering the story’s theme, a location surrounded by what remains relatively pristine upland hammocks and forested swamps makes perfect sense.

In Cross Creek, Rawlings wrote: “Someday, a poet will write a sad and lovely story of a Negro child.” This idea—which her editor, the legendary Maxwell Perkins, encouraged her to pursue—eventually took form in The Secret River, a slim illustrated volume that was published posthumously in 1955.

The book (and the opera) tells the story of Calpurnia, a bright young girl, a writer of poems, who ventures out into the wilderness to find a secret river where she hopes to catch fish for her destitute family. Not the sort of grandiose premise that might be expected from an opera, but charming nonetheless and ideal for families.

The ambitious work, three years in the making, was bolstered by grants from Opera America and the National Endowment for the Arts. It was composed by Stella Sung, a professor of music at the University of Central Florida, with a

libretto by Mark Campbell, who won the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for Music for Silent Night, a modern opera about a spontaneous but short-lived 1914 Christmas truce between enemy combatants in World War I.

Sung, who grew up in Gainesville, remembers childhood field trips to Rawlings’s home in nearby Cross Creek, now restored and maintained as part of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Historic State Park. When she learned about The Secret River, she read it and found it “irresistible”—particularly because of its roots in Florida.

In his retelling, Campbell expanded upon Calpurnia’s desire to be a writer and introduced a new character—none other than Rawlings herself. Sung’s score, although written for operatic voices, “manages to recall American musical theater in many wonderful ways,” says Campbell. “Some critics clutch their pearls at such populist notions; audiences never do.”

Soprano Kyaunnee Richardson will again lead the accomplished cast as Calpurnia. She’ll be accompanied, as she was in 2021, by players from the Orlando Philharmonic Orchestra and vocalists from the Opera Orlando Youth Company under the baton of Everett McCorvey, chair of opera studies at the University of Kentucky and founder and music director of the American Spiritual Ensemble.

Stage Director Ayòfémi Demps is a highly respected local performer and director whose recent directorial credits include White People by the Lake (Orlando Shakes Playfest); The Light in the Piazza (Central Florida Vocal Arts), Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grille (Theater West End); and Appropriate (The Ensemble Company).

Dennis Whitehead Darling, the stage director in 2021, had been scheduled to return this year. Tragically, however, Darling was killed in a motorcycling accident in May. The March performance will be dedicated to his memory and to that of Tracy Conner, founder of Orlando’s MicheLee Puppets, who died in 2023.

Those dazzling puppets—including many fish and a larger-than-life Florida panther, black bear and Great Blue Heron—will again enliven Calpurnia’s perilous journey home. The production will also feature dancers from Inez Patricia School of Dance.

The Secret River stands out as a rare operatic vehicle for an African American ensemble, note its creators. Opera Orlando, then, can rightfully celebrate its role in diversifying the genre. After all, according to the lyrics of one aria from the production, “Each new day is a reason to sing.”

In the segregated society of 1955, the race of the characters in Rawlings’s Newbery Medal-winning book was never mentioned. The first edition was printed on coffee-colored-paper so the illustrations would be racially ambiguous.

Rawlings, according to biographers, was a brilliant but eccentric writer who swore, chain-smoked and drank too much. She tended her groves, hunted and fished in the untamed backwoods and, accompanied by a friend, explored the St. Johns River in a small wooden motorboat.

She also recognized her own racial prejudices—and worked to overcome them—after forging a friendship with folklorist Zora Neale Hurston. Eventually, the sometimes-ornery author became a vocal critic of racism and an advocate for racial justice.

“I hope that audiences find commonality, truth and inspiration from this positive depiction of an African American family during one of the worst economic times the country has ever faced,” said Darling prior to the debut in 2021. “The more we tell stories that include characters of color, the more we give a voice to those marginalized and oppressed groups.”

Mead Botanical Garden is located at 1300 South Denning Drive, Winter Park. Attendees are encouraged to bring blankets or lawn chairs and stay after the show for a talkback with the cast and the puppeteers. Tickets, which are $39.50, can be purchased through simpletix.com or by calling 407-512-1900.

—Randy Noles