Every once in a while, a story in Winter Park Magazine, such as “Water Line” in the Fall 2025 issue, makes a major splash (no pun intended). According to Facebook analytics, some 94,000 people on that platform viewed the story because it was shared so many times. Hundreds of others commented on the post—generally in thoughtful and articulate ways.

“Water Line,” which delved into the decidedly uncomfortable history of swimming pool segregation in Winter Park, pointed out that Cady Way Pool in Winter Park Pines was built in 1962 not by the city—which didn’t take over ownership until 1980—but by a private club for the express purpose “of avoiding the possibility of segregation.” (Restricted access to public recreational facilities such as swimming pools had become a racial flashpoint across the country.)

Three months later, the West Side Pool—a project originally initiated by a grassroots biracial organization but ultimately owned and operated by the city—was completed for the use of children who were then unwelcome at Cady Way.

Shortly after the West Side Pool’s debut in what is now Martin Luther King Jr. Park, a group of white children surprisingly showed up to swim there—an occasion so noteworthy that the city’s chief of police, Carl D. Buchanan, personally investigated a call from (as far as we know) a concerned citizen.

In addition, there was significant coverage of the curious event in the

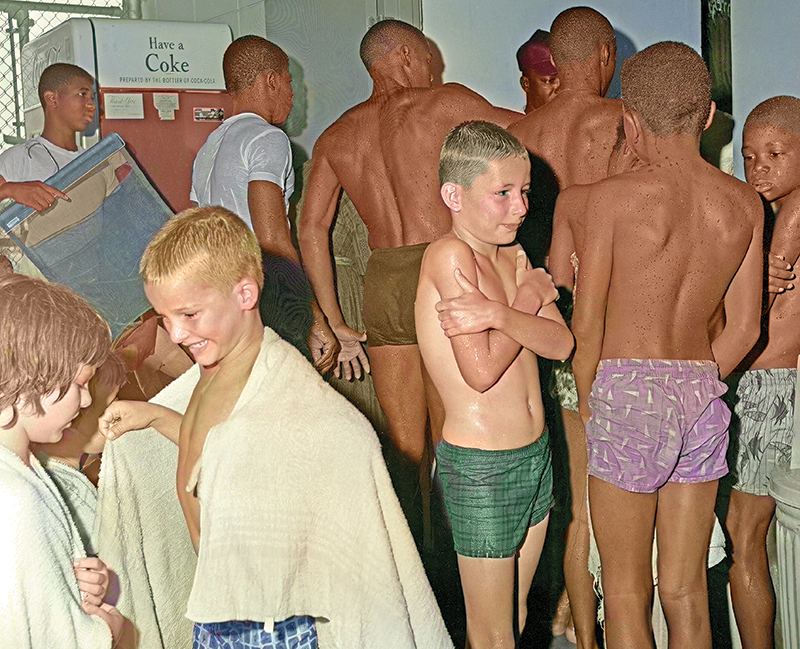

Orlando Sentinel, including a large photograph that showed a mixed-race gaggle of dripping youngsters accompanied by a story that pointedly described how well the children played together “in an unselfconscious manner.” We ran an artistically colorized version of that same photograph in our fall story.

I wondered: Who were these children? What compelled the chief of police himself to respond to a call about their presence? How did a Sentinel photographer happen to be on hand? It appeared to me (and I speculated about this possibility in my story) that the situation may have been arranged by adult activists opposed to segregation.

Or, as it turns out, maybe it wasn’t that complicated. Shortly after the magazine came out, I heard from one of the children in the photograph, Carl Berkey, who was 8 years old at the time and is now retired and living in Vancouver, Washington.

Carl saw the story—someone sent him a copy—and called me to identify himself as the towheaded little boy in the foreground wrapped in a white towel. He was accompanied that day by his late brother, David, shown on his right, and his sister, Suzie, shown on his left.

The Berkey family lived on Pennsylvania Avenue near the railroad tracks (the small house is still standing) and both parents worked. So the children had a Black babysitter who watched them after school. It was she who, somewhat audaciously, suggested that her charges might want to swim in the city’s new pool, where her boyfriend worked as a lifeguard. A real pool? You bet they did!

Carl doesn’t know who saw them there and summoned the police—“just somebody who was curious, maybe”—but he recalls that the chief quizzed Suzie, who explained the situation. Just to be sure, a call was also made to the childrens’ mother, who worked at the Ben Franklin Five & Dime on Park Avenue. She confirmed that, yes, she knew where her brood was and had no concerns. Buchanan, according to the Sentinel, “said no more and left.”

Notes Carl: “We weren’t taught racial hatred or anything like that. None of us thought anything about [the West Side Pool] being a pool for Black people. I’m not sure we even knew that. You could have told us that it was a pool for Martians and we would have just been excited to swim in nice, clear water.”

I also heard from Gary White, son of the late Nick White, who was the Sentinel photographer who took the photo and wrote the accompanying narrative. Nick White worked for the newspaper, mostly through its bureau in Winter Park, from 1961 to 1966. (Yep, until 1998 the local daily had a bureau here staffed with at least one reporter and a photographer.)

In 2023, Gary White curated a sampling of his father’s news photographs and collected them in an informative time-capsule of a book, Winter Park in the 1960s, which was published by Arcadia Press. (Documented in the book’s pages are the construction of a new city hall, the openings of new businesses and various civic goings-on.)

Probably, Nick White was there because he—like most reporters at the time—monitored police radio calls. If so, he would have heard a dispatcher describe a suspicious incident involving white children at the West Side Pool. Being a good newsman—and considering the fraught racial tensions of the era—he would have certainly checked it out.

But instead of deciding that there was really no story, the Sentinel shutterbug astutely realized—and his bosses agreed—that the complete lack of angst over this seemingly subversive (for the time) incursion was itself an important story that needed to be told and shown.

They say every picture tells a story. The Berkey children, of course, weren’t crusaders. They were just local kids who wanted to swim and didn’t care whether the other swimmers were black, white or green. Still, the image snapped that day sent a message of hope in a turbulent time. To understand it, all any grownup really had to do was to look at young Carl’s smiling face.