Despite its founding by progressive New Englanders and its reputation for enlightenment, genteel Winter Park was inexorably part of the Jim Crow South. That fact manifested itself in many ways and in many settings—including swimming pools.

Although Cady Way Pool today is owned by the city, that hasn’t always been the case. Planning for the project, in fact, began in early 1958 with formation of the nonprofit Recreation Association Inc., an ad-hoc consortium of well-regarded citizens and representatives of local civic organizations.

The goal, seemingly, was a noble one: to find a suitable location on which to build and operate a first-class swimming pool for the benefit of the community—and to do so without using taxpayer dollars. But one of the reasons for structuring such a project as a private nonprofit was, shall we say, less noble but not unusual for the time.

In 1958, a pool owned in this manner could legally exclude African Americans. An Orlando Sentinel story about an early meeting of pool proponents matter-of-factly described the association’s purpose as “specifically to build a pool for white children.” Private ownership was required, organizers explained to a reporter, to “eliminate the possibility of future integration.”

Language in the association’s charter was somewhat more carefully phrased. One of its missions, according to the document, was “to make possible at a minimum cost membership in [the] organization to any desirable person or family.” What, precisely, characterized a “desirable person or family” would have been well understood.

Such a situation was not, at the dawn of the civil rights era, unique to Winter Park; between 1950 and 1962, more than 20,000 private swim clubs opened in white suburbs across the country for similar reasons. Some existing municipal pools, in the meantime, were beset by violent racial confrontations. Others simply shut down swimming pools, public parks and other recreational facilities rather than extend their use to Blacks.

Against this backdrop, local pool boosters—whose racial attitudes, it must be said, were relatively mainstream for the era—estimated that their project would cost about $125,000, the equivalent of about $1.4 million today. Fundraising, however, was surprisingly tepid, especially considering apparent public enthusiasm.

Indeed, a healthy 1,300 memberships in what was called the Winter Park Swim Club were sold in advance. A “lifetime” membership cost $100 per family, while a renewable annual membership cost $5 per family. There would also be “nominal” individual usage fees. And the location—inside the just-annexed Winter Park Pines subdivision—was easy to access.

Further, more than 200 people served on various pool-related subcommittees, indicating considerable grassroots support. Yet, by the end of 1961, the association had raised only $43,000—about one-third of its goal—through door-to-door solicitations, “pool parties” at private homes and general appeals through the media.

Pool construction, which had begun that summer, ceased due to a lack of funds. Then, in spring 1962, some 35 boosters guaranteed bank notes of $2,000 each and clinched a $70,000 loan to the association from the Commercial Bank of Winter Park. Additional collateral included a mortgage on the site itself, which had been donated to the association by Winter Park Pines Ltd.

Cady Way Pool opened in June 1962 to great hoopla, with several thousand people attending dedication ceremonies that included exhibitions of swimming and diving, as well as live music and a fashion show. Citizens of the west side, however, knew that none of this was meant for them.

“We’d go to Dinky Dock, Franklin Park in Eatonville and out to New Smyrna Beach,” says Mary Daniels, 80, who was born on the west side and remains among the neighborhood’s chief historians. “As Black people, we knew where we could go and where we couldn’t. Nobody had to tell us. That’s just how it was.”

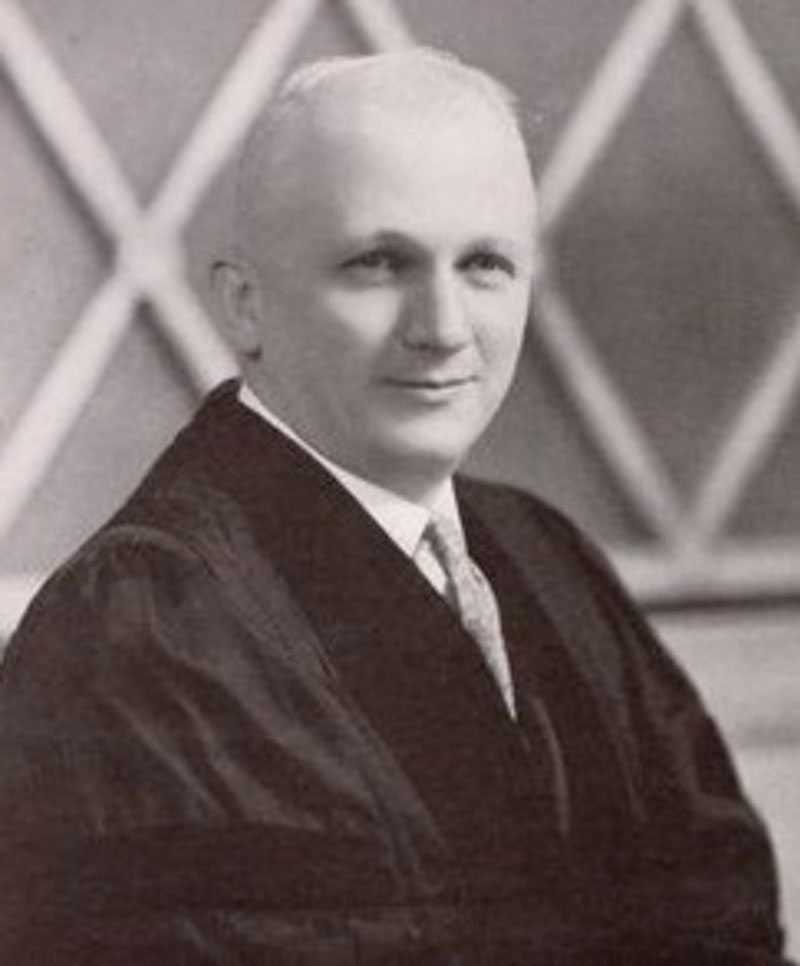

But in December 1961, a retired (and respected) academician, Dr. Paul L. Thompson, had joined forces with African American community leaders to form the biracial West Side Swimming Pool Association (WSSPA). Thompson—who had served as president of Kalamazoo (Michigan) College—was active in the University Club, the Rotary Club and the First Congregational Church of Winter Park.

WSSPA’s goal was to raise $50,000—the equivalent of about $540,000 today—for construction of a Junior Olympic-sized pool “for the use of the Negro community,” according to the Orlando Sentinel. Noted Thompson: “The Negroes have started this effort on their own initiative. This fact is most significant. We must not fail to help carry this through.”

Within weeks, there were hundreds of individual donations—mostly from white residents—and the city quickly agreed to provide matching funds of up to $25,000 (or more, if necessary) to make certain that the pool was built. The finished facility would be owned by the city and operated by its Parks & Recreation Department. No fees or memberships would be required for usage.

The West Side Pool opened in October 1962—four months after Cady Way—with ceremonies that included bands from Jones High School in Orlando and Hungerford Preparatory High School in Eatonville. Several hundred people gathered to celebrate this separate (but not exactly equal) facility located in city-owned Lake Island Estates—which would in 2012 be renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Park.

To add a layer of vexing backstory, the 23-acre tract—previously a neighborhood for Blacks—had been acquired by the city in bits and pieces during the 1950s through purchases and, in the case of those who refused to sell, condemnations and relocations. This uncomfortable fact remains a source of indignation for some long-time west side residents.

The plan for the property was to develop a host of cultural and recreational amenities—perhaps including a convention center—that would attract corporate meetings and draw tourists who patronized the plethora of mom-and-pop motels that lined nearby U.S. 17-92’s so-called “million-dollar mile.” Yet, for a variety of reasons—including, but not limited to, competing visions and ballooning costs—the grand scheme never materialized.

“We were all just ecstatic to have the pool,” says Daniels, who remembers having previously discussed the matter with her family physician, a beloved figure in the community, who agreed with her that the status quo was unacceptable. That same physician, however, also led the drive to organize segregated Cady Way. At the time, few would have detected any dissonance in these seemingly contradictory positions.

Why would they? Surely the well-respected physician and most of his peers did, in fact, strongly believe that Blacks who had no place to swim in the city were being dealt an injustice. But the remedy, most reasonable white people agreed, was simply to build another pool—not to integrate the pool that already existed.

After all, during the segregation era, white largess had funded the Hannibal Square School (1890), the Welbourne Avenue Nursery and Kindergarten (1931), the Hannibal Square Public Library (1937) and the Mary Lee DePugh Nursing Center (1956). Further back, the city had been founded by abolitionists who encouraged homeownership among Blacks.

Although support of west side civic projects may now be seen as paternalism, benevolence or a combination of both, there is no question that white residents were usually generous when rallying around such efforts. Almost certainly this history of philanthropy contributed to at least a veneer of comity while other cities experienced upheaval.

“Winter Park always thought of itself as setting a tone different from the rest of the South,” says Julian Chambliss, a former professor of history a Rollins College who made an ongoing case study of the west side during his years in Winter Park. “In various ways it tried to avoid open conflict and locally there was never a flash point. But the underlying tension was there.”

With the adults, sure. But the kids, it seemed, mostly just wanted to swim. In fact, the first notable instance of aquatic race-mixing in Winter Park happened not at Cady Way but at the West Side Pool.

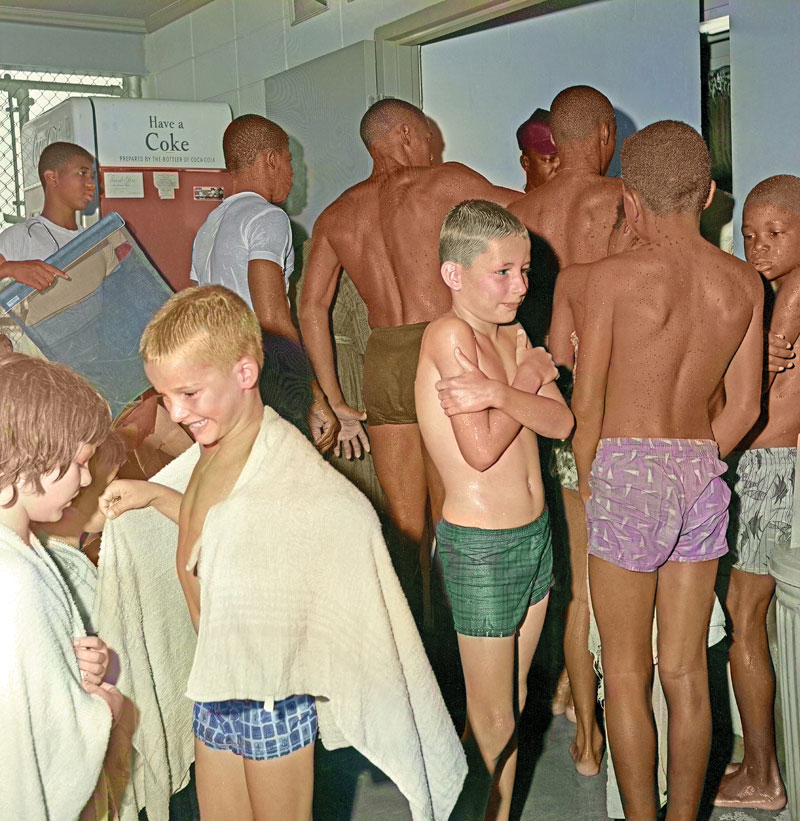

In June 1963, an odd story headlined “Winter Park White Children Integrate Pool” appeared in the Orlando Morning Sentinel. The story, which has no byline, explains that “five unidentified white children used all the facilities of the pool in an unselfconscious manner and aroused no signs of resentment or even curiosity from the Negro children.”

This event was so notable that someone called Chief of Police Carl D. Buchanan, who, according to the story, arrived and asked the white children if they had parental permission to be at the pool. After the white children affirmed that their parents knew where they were, the chief “said no more and left,” almost as if on cue.

The white children, it was dutifully reported, then resumed playing and “did not stay in a group together, but mixed completely with other children their age, about 6 to 10 years old.” At the top of the page is a photograph—snapped by a Sentinel photographer—of the anonymous (but surely recognizable) interlopers and their new west side friends, dripping and smiling.

That was it. That was the whole story. Except, of course, it wasn’t. The all-too-convenient circumstances were almost certainly orchestrated—with the city and the newspaper in cahoots—by someone who wished to make a point about the ability of youngsters to ignore the prejudices of their parents.

Perhaps the instigator was Thompson, who had previously received favorable news coverage for his pool crusade. Two months later, perhaps not coincidentally, Thompson spoke to the Winter Park Rotary Club about the dangers of racial stereotyping. “I’m often labeled as for the Negroes,” he told the Rotarians. “I’m not for the Negroes or for any other race. I’m for decency in the world.”

Meanwhile, as the Bob Dylan song points out, the times they were a-changing. First, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in public accommodations—a step in the right direction—and many city-owned pools (including those in Orlando, which had integrated its parks but closed its pools the prior year) were officially open to everyone.

But the act left a loophole for private clubs that many swim clubs, including the Winter Park Swim Club, exploited. Finally, in 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court specifically prohibited swim clubs—which it described as essentially operating neighborhood amenities—from denying membership to those who lived in the facility’s service area based on their race.

In 1980, Recreation Association Inc.—and by extension the Winter Park Swim Club—became insolvent and the corporation was “involuntarily dissolved” when the city took over ownership of Cady Way. It is unclear whether or not the club, in light of the ruling, had ever formally rescinded its policy of segregation. In any case, once the facility was publicly owned, the issue became moot.

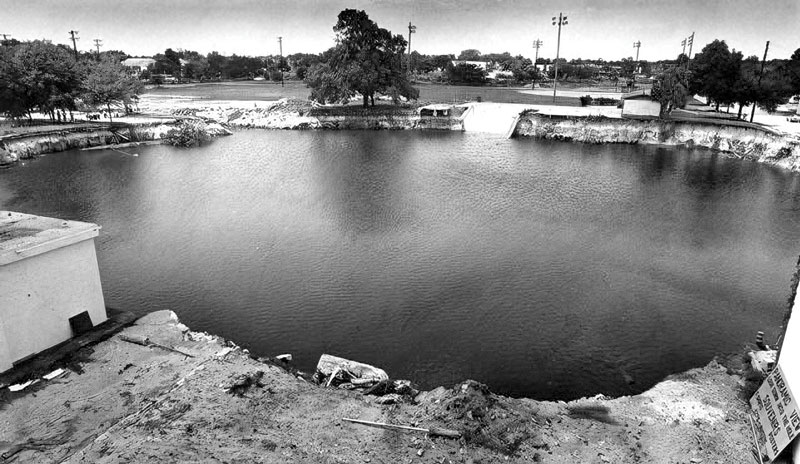

Today, you won’t find any sign of the place where children of different races made news (well, perhaps manufactured news) by swimming together in the same water. On May 8, 1981, the pool—along with a home and, famously, several Porsches—was swallowed whole by the infamous sinkhole known today as Lake Rose.

In 1982, using a $250,000 state grant, the city built a replacement West Side Pool adjacent to the Winter Park Community Center on West New England Avenue. In 2011, that 40-year-old building was demolished and replaced by a $9 million, 38,000-square-foot multiuse facility with a new, improved pool behind it instead of alongside it.

Although the original West Side Pool had been free to use, that was no longer the case once the first iteration of the sinkhole’s successor opened. That’s when the city—after receiving some (rather ironic) gripes from white east side residents about unequal treatment—adopted fees that mirrored those in place at Cady Way.

Happily, at both municipal facilities, the only color that matters any more is sparkling blue. Yet the legacy of segregated pools continues to linger. Numerous studies show that Black children are disproportionately more likely not to know how to swim, which is reflected in drowning rates.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, African American children between the ages of 10 to14 drown at rates 7.6 times higher than white children, and are more likely to drown in public pools. These race-based disparities in drowning deaths have persisted in the U.S. despite a 32% decline in total drowning rates since 1990.

“In the beginning of the 20th century, Blacks swam more than whites—at the end of the century, whites swam more than blacks,” says Jeff Wiltse, a University of Montana history professor who has studied the issue. “I mean, this is a historical problem.”