Do you want to hear some juicy insider information about what’s happening at Rollins College? Well, you can always ask the delightful but dauntingly discreet Lorrie Kyle Ramey. Not that she has anything juicy to share. Not that she’d share it even if she did.

Kyle (as she is known professionally) doesn’t even like to talk about herself, although she’s one of the most interesting and accomplished people on campus: administrator, playwright, historian, literary scholar and aficionado of clouds in all their vapory variety.

Her job title — which seems inadequate to describe what she means to the college — is executive director, office of the president. She has held more or less the same role, but with increasing levels of responsibility, for 33 years and through the administrations of four presidents.

Her bosses have included Rita Bornstein, from 1990 to 2004; Lewis Duncan, from 2004 to 2014; Craig McAllister (who served as interim president), from 2014 to 2015; and now Grant Cornwell, who has presided over a building boom that rivals any at the college since the Hamilton Holt era in the 1920s.

Although Kyle has told all the presidents since Bornstein that she’d step aside if they wished to select someone else — perhaps, given the nature of the job, someone with whom they’d previously worked — obviously none have taken her up on the offer.

They were quickly sold on the uniquely qualified Kyle — who had graduated from Rollins in 1970 and whose mother-in-law, Phyllis Ramey, had for decades held various administrative positions at the college, among them executive assistant to President Jack Critchfield.

So, following the hard-charging Bornstein — a prolific fundraiser who today considers her former executive assistant to be a cherished personal friend — Kyle remained in her accustomed position as an administrator, a counselor and a confidant for Duncan, McAllister and Cornwell.

In addition to valuing her administrative savvy and unflappable demeanor, each president has found that access to Kyle’s storehouse of institutional knowledge has been critical when they addressed vexing problems or challenges.

“Lorrie is never not working,” says Cornwell. “There are no degrees of separation between Lorrie and Rollins. She has lived a life of service and has had tremendous influence on everything that makes the college what it is today. Her humility means that most of her influence and contributions go unnoticed.”

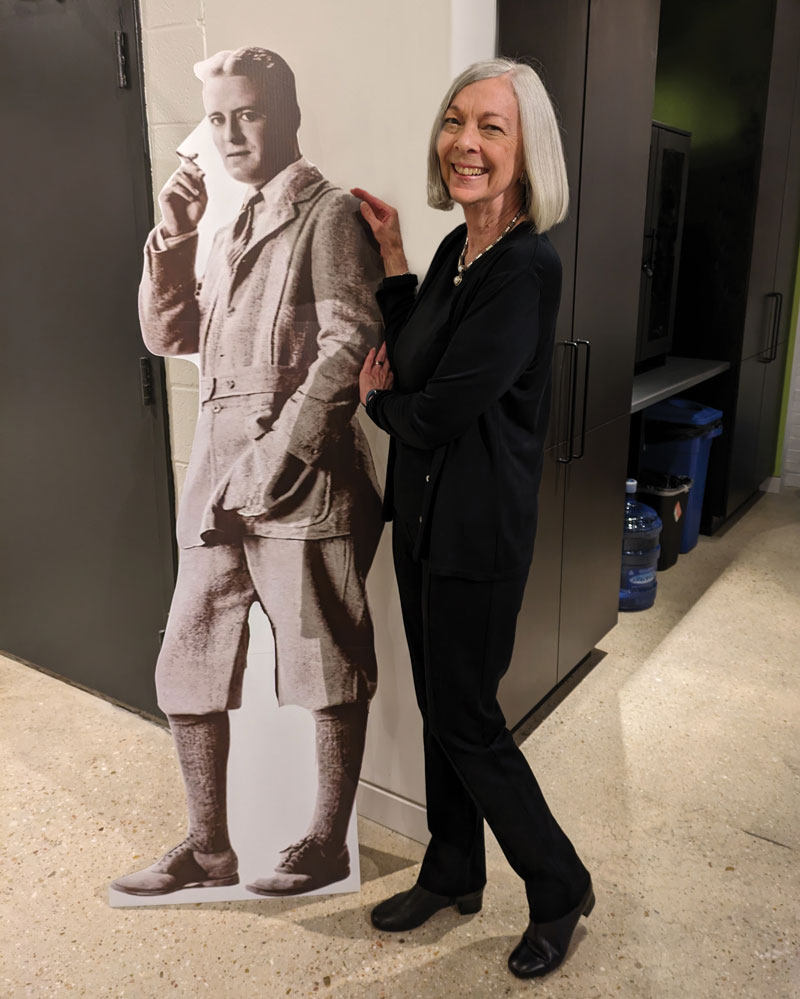

That’s fine with Kyle, who describes herself as “an under-the-radar” type of person who isn’t defined solely by her job in the Warren Administration Building. She’s also a writer whose play based upon correspondence between F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald has received two staged readings and will likely be produced when rights issues are resolved.

In addition — and perhaps more unexpectedly — she’s a dedicated cloudspotter and a member in good standing of the U.K.-based Cloud Appreciation Society, whose website was once described by Yahoo! as “the most weird and wonderful thing on the Internet.”

But before you dismiss this as a literal head-in-the-clouds pastime for idle daydreamers, a descriptor that decidedly does not fit the uber-conscientious Kyle, then you should know that in 2017, thanks to the society, the World Meteorological Association added a new cloud — dubbed “asperitas” — to its International Cloud Atlas.

Says Cornwell: “This is just another example of Lorrie’s quiet attentiveness to, well, everything.”

Developer Allan Keen, the longest-serving member of the college’s board of trustees and chairperson from 2006 to 2008 and again from 2016 to 2019, attended Rollins at the same time as Kyle and her future husband, Dan Ramey (son of Phyllis), although they weren’t then acquainted.

Away from home for the first time and holding down an off-campus job while carrying a full schedule of courses, Keen remembers Phyllis — who spent nearly 30 years at the college and became legendary on campus and in the community — as being “warm and welcoming; she took care of me on a number of personal matters and was a special lady.”

As fate would have it, Keen would come to depend on Phyllis’s daughter-in-law even more, albeit for different reasons, in his later role as a trustee member and chairperson. “I describe Lorrie as a quiet leader, an exceptionally detailed leader,” he says. “She never seeks the limelight but is the true keeper of knowledge.”

Adds Cornwell: “I count on Lorrie as a sage counselor. Hard things pass over a president’s desk, and I count on her as a trusted conversation partner.”

LEARNING HOW TO LEARN

“There’s something special about this place,” Kyle says of Rollins. “I learned how to learn here.” Her circuitous journey to Winter Park began in Canada, where she was born, and continued through Miami, where her family moved when she was a child to be near her maternal grandparents.

She came to Rollins because of its strong theater department, then headed by Robert Juergens, a creative force of nature who chaired the Theater Arts Department and was director of the Annie Russell Theatre. But Kyle — not surprisingly — preferred technical theater to performing on stage.

“I was intrigued by lighting and stage managing,” says Kyle, who initially pursued a double major in technical theater and English. “That’s what I like to do — keep the train on the track.” She stage-managed five plays, including her favorites: Black Comedy (with playwright Peter Shaffer in the audience) and Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Kyle was also accepted into Theta Alpha Phi, the national theater honor society, and was routinely named to the Dean’s List and the President’s List. She was rush and social chairperson for her sorority, Phi Mu, while serving as editor of The Flamingo, the campus literary magazine, and literary editor of The Sandspur, the student newspaper.

In addition, Kyle was a member of Omicron Delta Kappa, the campus chapter of a national leadership honor society. Because ODK didn’t accept women when it was chartered in 1931, the college had founded its own whimsically named “Order of Libra” several years later. The only male member: President Holt, a long-time social-justice crusader.

The complementary confederations had merged in 1975, when ODK’s national office voted — belatedly, to be sure — to extend eligibility to women. Kyle, however, believed that gender equity should be retroactive, and marshalled an effort to persuade ODK headquarters that past Order of Libra members should be “grandmothered in.”

That phrase may be taken both literally and figuratively. “The first person we initiated was from the class of 1940,” recalls Kyle. “She was living in Winston-Salem and was initiated on her 90th birthday. It was fascinating to hear her, as well as other women, talk about their experiences at Rollins.”

Kyle has remained active in ODK at Rollins as a faculty/staff initiate and “circle coordinator” for more than two decades. In 2022, she was a recipient of ODK’s Eldridge W. Roark Jr. Meritorious Service Award.

The other recipient that year was presidential spouse Peg Cornwell, who works in college and community relations and was a faculty/staff initiate and circle coordinator at her alma mater, St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York. Naturally, she has been supportive of Kyle’s efforts at Rollins.

Ultimately, Kyle decided to forgo her double major and concentrate only on English, with the goal of becoming a literature teacher. She graduated from Rollins in 1970 — with distinction, of course — and was then off to Nashville and Vanderbilt University, where she earned an M.A. and a Ph.D.

Yet, even after accumulating three degrees in English, she switched gears and became — of all things — a commodities broker. Teaching, it turned out, was the one thing she couldn’t seem to master.

“I learned from my graduate teaching assistantship that I wasn’t comfortable in front of a class,” says Kyle, who still avoids teaching despite her impressive credentials. “I’m a perfectionist. I wouldn’t want students not to have the best experience that they could.”

In 1979, Kyle returned to Orlando and became a trading assistant with ContiCommodity Services, the brokerage subsidiary of Continental Grain Company, and quickly worked her way up to broker. “I like to tell people that I left Nashville because my country music career didn’t work out,” she deadpans.

The following year, Kyle and Dan Ramey — now retired but then a special markets representative for Dean Witter — reconnected at their Rollins 10-year reunion and were married. Along with a husband, Kyle also got a mother-in-law who would soon change the course of her life and set her career at the college in motion.

But not quite yet. After several years working for brokerages, Kyle and Ramey set out on their own — barnstorming the country and delivering financial seminars primarily for doctors. Kyle at first thought that business travel would be glamorous, but soon found it less exciting and more exhausting.

So, making another career change, she came off the road to take a leasing management job with Houston-based RIDA Development Corporation, a commercial real estate company that was building the first phase of the Renaissance Centre just west of the Altamonte Mall.

Meanwhile, back at Rollins, President Thaddeus Seymour — a beloved figure and among the college’s most consequential presidents — announced his retirement. (He would go on to teach at the college for 19 years and, with his wife, Polly, become an iconic community volunteer.)

Phyllis, too, had just celebrated a fond farewell from the workaday world. Then, in a twist of fate that would have enormous ramifications for the college in general — and for the world’s most overeducated commercial leasing manager in particular — the veteran administrator was asked to stay on a while longer and staff the search committee for the college’s 13th president.

RIGHT PLACE, RIGHT TIME

Rita Bornstein, vice president for development at the University of Miami, was ultimately offered the presidency and became the first woman to hold that position at Rollins. She was the ideal choice, according to Phyllis, who had identified the no-nonsense native New Yorker as her personal front-runner beginning early in the search process.

“After I was offered the job, Phyllis came to me and said, ‘I know the perfect candidate to be your executive assistant,’” recalls Bornstein. “She said it was her daughter-in-law.”

Perhaps partly out of courtesy and partly out of the regard in which she had come to hold Phyllis, Bornstein agreed to meet the Rameys — Dan, Phyllis and Lorrie — for breakfast at a local restaurant. “But I just couldn’t quite get a bead on Lorrie,” recalls Bornstein, who was no shrinking violet. “She was so quiet. I just wasn’t sure.”

So, she invited the Rameys — this time a foursome that included Phyllis’s husband (and Lorrie’s father-in-law), Deem — to have lunch at the president’s residence, where Bornstein was settling in with her husband, Harland G. Boland. “I cooked the only meal that I would ever cook at Rollins,” says Bornstein. “It was meatloaf.”

Still, Kyle — perhaps nervous because she knew that the luncheon was essentially an audition — spoke little. “So, I decided to conduct a search for an executive assistant,” adds Bornstein. “But I just couldn’t find a good fit and decided to go with Lorrie. It turned out to be the best hire I ever made.”

Confirming the cliché that still waters really do run deep, Kyle quickly proved that she would be no run-of-the-mill office administrator. Bornstein recalls being amazed by Kyle’s depth of knowledge and credits her with “introducing me to the college; she understood its values and principles, and knew everything about its history, its strengths, its weaknesses and its relationships. That was priceless for somebody new coming in.”

Kyle’s perfectionism was immediately put to appropriate use when Bornstein — who has a master’s degree in English literature — was horrified to discover that official correspondence from the college was often sent out containing misspelled words and grammatical errors. Says Bornstein: “Lorrie fixed that.”

It seemed to Bornstein that the multitalented Kyle could do just about anything: “To Lorrie, nothing was impossible,” she says. “Whenever I came up with a new idea, she could make it happen. No job was too challenging or too menial for her. She also has a wicked wit, which more than once rescued us from our excessive solemnity.”

The two women — despite (or because) of their contrasting personalities — did indeed make quite a team. Bornstein even came to depend upon Kyle to help shape the tone of her responses to absurd requests or demands from various college constituents — including, in one case, an irate parent who demanded that his son’s low grade in a class be raised.

In moments such as this, Bornstein admits that she might have replied in a less filtered manner had she not eased her exasperation by first talking it through with the ever-calm (and ever-calming) Kyle. “Those kinds of things happened a lot,” says Bornstein. “I can’t tell you about most of them.”

Kyle says that her favorite technique to reorient her boss following irritations and annoyances was to suggest that she simply roam the campus and absorb its energetic, intellectual vibe. “By the time she came back, she’d see things differently,” notes Kyle.

Today, Kyle and Bornstein are warm personal friends. “We have a very special relationship,” says Bornstein, who grew the college’s endowment from $39 million to more than $200 million by the time she stepped down. Kyle, who still assists her former boss with personal business matters, adds: “Rita taught me so much — and has helped me to grow in ways I can’t number.”

After Bornstein retired, however, Kyle had to reorient herself to an entirely different sort of leader. Lewis Duncan, who enjoyed many successes during his 10-year stint, was nonetheless censured by faculty members in 2011 after he established a new school — the College of Professional Studies — without their input.

Duncan was given a vote of no confidence in 2013 and resigned — not under pressure, he insisted — in 2014. But Kyle will only praise Duncan’s eagerness to draw upon his background as a physicist to help students with science-oriented research projects.

Known for never saying anything negative about anyone — at least not in public, and certainly not to a reporter — she’ll concede only that there may have been “a communications disconnect” in the case of Duncan’s ongoing faculty feuds.

Craig McAllister, the interim president who followed, was a known quantity as dean of the Crummer Graduate School of Business. Kyle describes him as “totally focused on students and fun to work with.”

As for Cornwell, she notes, he’s the first of her four bosses to have previously been a college president — a decided advantage. “Grant and Peg really embrace Central Florida,” she says. “They value collegiality and welcome input — and there’s a sense of trust.”

As for Kyle’s job, it has evolved — the title has been upgraded from “executive assistant” to “executive director” — but still encompasses many of the same elements: stage-managing events, researching background information for speeches, coordinating the president’s schedule and helping to resolve various issues on behalf of students and parents.

Perhaps her chief responsibility, though, is to organize the complex and often confidential work of the board of trustees as the college’s designated board professional — a position required of all colleges and universities.

In fact, that position is typically held by someone with a law degree, often the institution’s general counsel. But Kyle — the proud holder of those multiple degrees in English — is one of the most respected designated board professionals in the country.

She’s a member of the Council of Board Professionals, part of the Washington, D.C.-based Association of Governing Boards, and past chairperson of the organization’s Professional Leadership Group. “Lorrie has a national reputation in this regard,” notes Cornwell. “She’s the most trusted name in the field.”

JAZZ-AGE LOVE LETTERS

Despite holding down a demanding job, Kyle has recently gotten back to her literary roots. She’s the author of a play, Devotedly, With Dearest Love, which traces the doomed relationship between F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald through their love letters.

The play, which weaves its tragic tale almost exclusively through the couple’s own words, had its genesis in 2006, when the Albin Polasek Museum & Sculpture Gardens welcomed one of the first public exhibitions of Zelda’s paintings.

English professor Gail Sinclair, an active member of the F. Scott Fitzgerald Society, heard about the project and proposed that Rollins, where she taught, concurrently host a Fitzgerald symposium during which noted experts would discuss these icons of the Jazz Age.

To help pay for the event, the college could tap into the Thomas P. Johnson Distinguished Visiting Scholars Fund, for which Kyle was the manager and Sinclair was the academic coordinator.

As the pieces came together, Kyle and Sinclair decided that a staged reading of letters between the Fitzgeralds — some passionate and some poignant — would make an ideal symposium offering

In 2002, Fitzgerald scholars Jackson R. Bryer and Cathy W. Barks had published a chronological collection of those letters — which numbered 333 — in Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda: The Love Letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. The missives trace the ups and downs — mostly downs, sadly — of the couple’s tumultuous marriage.

“Lorrie picked up the gauntlet,” recalls Sinclair, now an author and private scholar. “This presented a perfect opportunity to meld her two academic passions — American literature and theater — and she did so beautifully.”

In the three months leading up to the symposium, Kyle — with structural input from Bryer and Barks, who gave the project their blessing — produced 15 drafts and joked that she “had spent my weekends with an alcoholic [Scott] and a schizophrenic [Zelda].”

One of her challenges: relating relevant events that the Fitzgeralds didn’t happen to write about. That was solved by using a magazine piece written by Zelda, letters that the couple wrote about one another but not to one another, and — in the case of Scott’s death — a contemporaneous newspaper account from the Los Angeles Times.

The play was staged in Tiedtke Concert Hall using a spare set. A Rollins student played period music during selected transitions as a venue filled with Fitzgerald specialists — including Bryer and Barks — watched and listened.

Kyle says reviews from the toughest audience imaginable were encouraging — but she put the project aside when complex rights issues emerged that involved the F. Scott Fitzgerald Estate and the holders of an option to make a film about the life of Zelda.

“The play remained on the bookshelf, but never out of my mind,” notes Kyle. “In 2021, a fresh reading left me as convinced as I had been 15 years earlier that the letters were too compelling to be left silent. I wrote to Jackson Bryer and Cathy Barks, and a new chapter opened.”

In 2023, with special permission from the estate, another reading was held in conjunction with the 27th Annual F. Scott Fitzgerald Literary Symposium in Rockville, Maryland.

The mini-revival was staged by The Rose Theater Co., a performing-arts nonprofit in Bethesda, Maryland, dedicated to fostering new plays. Hopefully, says Kyle, the recent reading won’t mark the play’s finale.

Eventually, if the estate’s cooperation is secured, Kyle hopes the play will be published and performed widely. “I’d especially like it to be available for high schools and colleges,” she says. “I’d like people to have the opportunity to hear that language.”

Sinclair agrees: “What Lorrie has produced is a wonderful tribute to [the Fitzgeralds], to their interesting and adventurous lives together and to the artful use of language that both Scott and Zelda demonstrated in their separate as well as their jointly written publications.”

WORTHY OF MEATLOAF

There’s more to say about Lorrie Kyle, who is arguably the most interesting person you’ve never met, unless you’ve had dealings with the president’s office at Rollins. And even if you have been to see Cornwell in person, you might have mistaken Kyle for his receptionist.

People used to say of Hamilton Holt: “Holt is Rollins and Rollins is Holt.” That phrase might well be adapted to substitute Kyle’s name, but the college’s legendary eighth president was — let’s face it — a shameless publicity hound who tried to reshape the institution that he dominated in his own larger-than-life image.

Kyle — who was, conversely, shaped by the college — has sought only to serve the presidents who have followed Holt, and to do so quietly and competently. Nonetheless, she has been both an integral part of the college’s history as well as one of its more prolific historians.

Her lively articles — including an entertaining chronological recounting of significant (and not-so-significant) events from 1885 through 1985 — routinely appear in campus publications and on websites. Just don’t ask her to teach a course about them.

In 2003, at commencement, Kyle was presented the Rollins Decoration of Honor by Bornstein, who said: “You personify the best of Rollins.”

And she meant it. After all, Kyle is the only person Bornstein ever prepared a meal for as president. “I know that’s true,” recalls Kyle. “I remember when Rita retired, and I related that story at an event. I could see her family gasp.”