At a time when they were seemingly without hope, the Bottom family met a Winter Park doctor who transformed — perhaps saved — their lives. Had this not happened, the world would likely have never heard of the actor siblings River and Joaquin Phoenix.

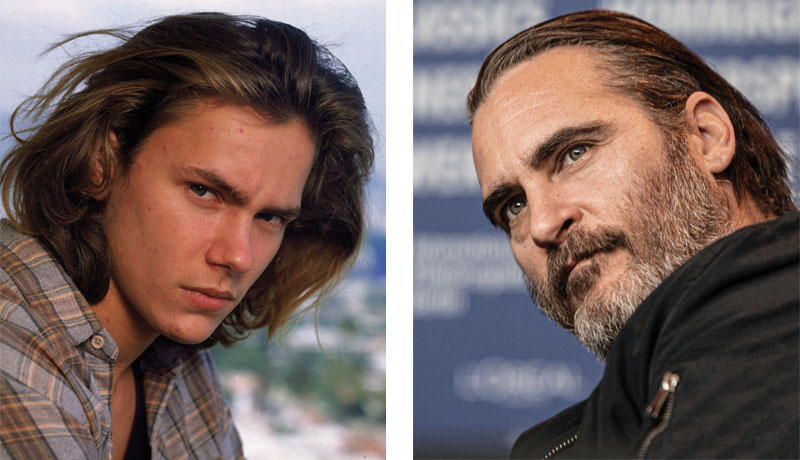

River — who died of a drug overdose in 1993 — was a 1988 Oscar nominee for Best Supporting Actor in the Sidney Lumet-directed drama Running on Empty, in which he played Danny Pope, a teen pianist who is hiding a dark family secret.

Joaquin — who for a time called himself “Leaf” since all his siblings had nature-themed names — won the 2021 Oscar for Best Actor in the Todd Phillips-directed Joker, in which he delivered a dark and disturbing tour de force as the film’s crazed title character.

For those performances and many others, film buffs can credit an obstetrician and gynecologist, Dr. Alfonso Sainz (pronounced SAY-nzz), who had formerly been a recording star of renown in his native Spain and happened to be vacationing in Caracas, Venezuela, in 1977.

“It was down by the beach, and two little kids were singing at the restaurant,” the physician later remembered. “I talked to them. I said, ‘I like you, you’re great.’” He asked the children — who introduced themselves as River and Rain Bottom — to return and sing again the following night.

Towheaded River, then age 7, already feeling pangs of responsibility to support his family, hoped something positive might come from such a meeting. He and Rain, then age 6, returned as instructed, along with their parents, John and Arlyn Bottom, and siblings Joaquin, then age 3, and Summer, then barely a year old.

“If you’re ever in Florida, look me up,” Sainz told the Bottoms, who looked like a hippified version of a scaled-back Brady Bunch. “I have a guest house in Winter Park.” Perhaps unexpectedly, the family would soon take Sainz up on his offer.

Patriarch John — who looked much like his adult son Joaquin does now — had become disillusioned with the Children of God — an authoritarian sect for which he and Arlyn were missionaries — and its practice of using offers of sex from female members to lure new members. There were also credible reports of pedophilia.

Said River in a 1991 interview: “My dad started finding out that the leader [founder David Berg, who died in 1994] was involved in fraud, a big hypocrite, and this group wasn’t as wholesome as they led people to believe.”

In fact, River later claimed to have been raped by cult members at age 4, although Joaquin insisted that his brother had been joking about assaults as a response to continued “ridiculous questions” from the press.

Whatever the case, Sainz’s invitation was like a knot at the end of the Bottom family’s rope. With nowhere else to turn, John and Arlyn decided to set their family on a new course back to the United States and then to Winter Park.

“A priest got us on this old freighter that carried Tonka toys,” River recalled. “We were stowaways. The crew discovered us halfway home, all of us running around, four kids.” Luckily for the Bottoms, the kindly crew welcomed the family and even threw a birthday party for 4-year-old Joaquin complete with damaged Tonka toys as gifts.

Upon their arrival, Sainz allowed the entire Bottom clan to live on his Winter Park estate, where they would remain for almost two years. During that time, their host would deliver yet another sibling, Liberty, who was born at Florida Hospital South (now part of AdventHealth).

Also while living with Sainz, the Bottom children — about whom countless words would eventually be written — were mentioned for perhaps the first time in a newspaper. The Christmas Eve, 1977 edition of the Orlando Sentinel noted that River and Rain had performed for female inmates at the Orlando Municipal Jail, courtesy of Thee Door (now the Center for Drug-Free Living), where John had found volunteer work.

The brief account, which described the Bottom family as “holiday guests” at the Sainz home, was accompanied by a muddy photo of the siblings — with River strumming an adult-sized guitar — against a backdrop of steel bars with inmates gathered around to listen.

This was nothing new for the youngsters, who had been raised off the grid as their highly unconventional (and frequently destitute) parents preached the gospel across the Caribbean and South America.

As a matter of necessity, they frequently performed for tips as a way for the family to buy food — and were doing so in Caracas when they met a man who offered them a new home and new hope.

Sunshine Days

By the autumn of 1977, the dashing Sainz — who some say bore a resemblance to his friend Julio Iglesias, the Spanish heartthrob, while others insist that he looked more like Cuban bandleader Desi Arnaz — estimated that he had delivered 3,000 babies through his thriving practice.

Sainz — recently divorced with three children — was also an accomplished musician who had recorded several million-sellers and continued to pursue a solo musical career even after becoming a well-established physician. “My dad lived the life of 10 men,” says daughter Diana. “Maybe 20.”

As teens in Spain, Sainz and his brother Lucas were attracted to the music of such American rock ‘n’ rollers as Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and Elvis Presley. They formed their own five-person group, Los Pekenikes, in 1958, and began to place hits — often Spanish-language covers of U.S. pop radio favorites — on the Latin charts.

On July 2, 1965, Los Pekenikes — which had by then synthesized flamenco music with rock ‘n’ roll and played mostly original material — opened for the Beatles during a performance staged in a bullfighting ring in Madrid. That show would go down in musical history as the Fab Four’s only concert in Spain.

During that same period, Los Pekenikes notched a pair of gold records in Europe and Latin America. Their biggest seller was “Hilo de Seda,” which Sainz later rewrote in English and was recorded by John Davidson and Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass as “Sunshine Days.”

Sainz later met Iglesias, a Los Pekenikes fan, who performed several concerts with the group. But not everyone was overly impressed — not even the man who gave Sainz, then age 15, his first guitar and bandurria (similar to a mandolin) and encouraged him to learn to play them.

“My father, who was a lawyer, thought that to be a musician [as a profession] was something that didn’t look too good,” Sainz recalled in a 1993 interview. “I appreciate that he was always reminding me that the most important thing in life was a good education.”

Sainz, however, managed to thrive in both worlds. Los Pekenikes remained together for 12 years, making records and playing concerts on weekends and holidays while Sainz powered through medical school at the University of Madrid, from which he graduated in 1970.

Later that year, Sainz came to the U.S. to complete a medical internship at Orlando Regional Medical Center (now the flagship hospital of Orlando Health) and began an obstetrics and gynecology practice with Dr. Henry Schilowitz.

According to Sainz, the professions of music and medicine required similar skill sets. “To be a good doctor you need to be an artist,” he often said. “Medicine is an art. You do something to help people with their problems. That’s the same thing you accomplish with music.”

Often, patients recalled, Sainz practiced what he preached by bringing his guitar into hospital delivery rooms and serenading nervous parents-to-be.

In 1975, enjoying the rewards that come with being a successful physician, Sainz bought “The Ripples” in Winter Park. The 6,789-square-foot West Indies Colonial mansion, located on Forest Road and built in 1923, is still considered one of the city’s most distinctive historic homes. (It was sold in 2021 for $1.045 million — a bargain even considering the substantial repairs and upgrades required.)

Situated at the top of a hill overlooking Lake Sue, the sprawling property then encompassed a 2,200-square-foot, two-story guest house where the Bottoms family set up housekeeping. The guest house — now long since razed — was surely the most comfortable place the nomadic family had ever lived.

In the meantime, another Winter Park resident, musician Tim Coons — who would later earn Grammy nominations and become best known for his work with the Backstreet Boys — met Sainz, who was itching to release a solo album that would finally crack the lucrative U.S. market. Would Coons like to help?

“We would say, ‘You’re a gynecologist and a pop star?’” recalls Coons. “And he had money. Back then, no musician had money.” Sainz also had famous friends, says Coons, who once jammed with José Feliciano while the legendary guitarist was encamped at The Ripples during a concert stop in Orlando.

Quedate, the solo album, came to fruition at Orlando’s legendary Bee Jay Studios — a state-of-the-art facility that was the original home for what would become Full Sail University. The final product — a polished, pop-infused collection of originals and covers in Spanish and English — was produced by Coons and his friend Tony Battaglia, who would gain fame as a rock guitarist and composer of the title song in the musical Hairspray.

In addition to Coons and Battaglia, a who’s who of other top local players — dubbed by Sainz as The Latin Connection — participated in the sessions. “Yeah, that was pretty funny,” admits Coons, whose vocals can be heard on several cuts. “None of us were Latin.”

Sainz also announced plans for a new company — International Broadcasting Systems (IBS) — that would serve as a record label and encompass a recording studio, a publishing company and production facilities for Latin-oriented television projects. A warehouse on Acme Street in Orlando was retrofitted to house the operation.

“It was all first-class,” recalls Coons. “Alfonso just had boundless energy and positivity. He had made it big already — his band had played a show with the Beatles — but he still acted like a young kid trying to break into the business. It was always fresh for him.”

However, IBS lasted only a few years and never achieved the grand goals set by Sainz. “My first priority is taking care of my patients,” he had told the Orlando Sentinel when the company was launched. But perhaps even Sainz — the ultimate multitasker — came to realize that he couldn’t be a physician, a recording artist and a music industry mogul at the same time.

Personal turmoil also churned around him. Sainz’s wife had left him just prior to the arrival of the Bottoms, and his inlaws had vacated the guest house shortly thereafter.

Daughter Diana, still in Glenridge Middle School, stayed with her father and spent time with him in his recording studio during the school year. During the summer, she traveled to Spain and visited extended family. However, when she returned to Winter Park in the fall of 1977, she found strangers living in the guest house.

“My dad had just returned from South America, and two weeks later, [the Bottom family] were on the doorstep,” she recalls. “They were in survival mode. A better opportunity presented itself to them, no strings attached, and they took it.”

Sainz, despite his marital problems, had stood by his word to host the Bottoms. “I thought they were coming to stay for a week,” he chuckled in a 2013 video interview at Coons’s studio. “They ended up staying for a year.” Diana, from behind the camera, added: “Two years.”

But she couldn’t help but feel affection for the odd brood that her father had brought home: “Joaquin was so cute,” she says. “He was my favorite of all of them. His little hand always held my hand when we went up and down the steps between our houses. That’s what I remember about him.”

Though they had only the few possessions that they could carry with them when they fled the cult, the Bottoms ended up giving Diana the warmth that was missing from her own life.

“Going down there and spending time with them, it was like being with family I didn’t have,” Diana adds, her voice quivering. “They were so united. My family had just broken up. I never felt that kind of love.”

She often joined River and Rain singing their favorite tune, “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.” Mother Arlyn, a devout vegetarian, taught Diana to make and enjoy eggplant Parmesan.

To be sure, Diana still adored her father, whose generosity of spirit was without question. Along with letting John and Arlyn and their children stay rent free in the guest house, he paid John to take care of the landscaping and Arlyn to assist the family maid with cooking and cleaning.

The couple, in a nod toward normalcy, also insisted that the eldest children be enrolled in school — a first for either of them. With that, River and Rain became the new kids at Audubon Park Elementary.

For River, acclimating was difficult. Not only had he never been to school, he hadn’t even watched television until he lived with Sainz. There had been nothing about his life that was similar to the lives of sheltered suburban children from Winter Park.

“When I was in first grade, everyone made fun of my name,” River later remembered. “[River Bottom] seemed goofy. I used to tell people I wanted to change the world and they used to think, ‘This kid’s really weird.’”

It’s doubtful that many, if any, of his first-grade peers — now in their early 50s — are aware that the curious classmate whom they remember as River Bottom went on to star as River Phoenix in such enduring films as Stand By Me, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and My Own Private Idaho.

Sainz even included the children in a handful of local performances to promote his solo album. Billing himself as “The Singing Doctor,” he asked River and Rain to perform with him in concert at the old Winter Park Mall. (He also performed benefit concerts at Rollins College.)

Coons, who also played live shows with Sainz, remembers River and Rain singing backup at the mall gig. “Alfonso never told us who these kids were and what their connection to him was,” says Coons. “We used to see the family around when we were at his house. But knowing the story now, it just reinforces what a giving, caring person he was.”

In 1978, Arlyn became pregnant with the couple’s fifth child. “The memory is very vivid,” Diana says of watching Arlyn’s pregnancy progress. “I’d never been around someone that pregnant before.” The arrival of little Liberty only strengthened the once-ruptured family vibe around The Ripples.

There were, of course, a few disagreements between Sainz and his guests. John — who hated cruelty to animals — was openly critical of his hosts for owning and wearing fur coats. At times Diana was made to feel guilty about having so many possessions, most egregiously an excess of clothing.

None of the Bottoms’ opinions and eccentricities ever stopped Sainz from being a generous benefactor. Yet, he had begun to grow restless: “I was tired of private practice, and I wanted a new challenge,” he said in 1993. “The world world was bigger than Orlando. Europe and the rest of the world was there for me to discover.” (Or, in the case of the worldly Sainz, to rediscover.)

In 1979, Sainz put The Ripples up for sale. That meant the Bottom family would also have to move along. But before they went their separate ways, Diana recalls her father telling John and Arlyn that they should consider taking their children to Hollywood. “My father recognized this talent with them,” she adds.

Shortly after ending this chapter of their lives, John and Arlyn changed their last name to Phoenix — an apt description of how they’d risen from the ashes and regained their footing, thanks to the Singing Doctor.

Triumph and Tragedy

Diana Sainz married young, had a baby and ended up moving with her husband to Denton, Texas, a suburb on the northwestern outskirts of Dallas. During a casual conversation with two teenaged neighbor girls, she mentioned the missionary family that had lived at their home in Florida.

She had neither seen nor heard from them since 1979, she said, but would always remember their unusual names: River, Rain, Joaquin, Summer and Liberty. “They looked at me funny,” recalls Diane. “Then they said: ‘Hold on a second.’”

The girls retrieved the latest issue of Teen magazine and flashed the cover — which featured teenage celebrities River and Joaquin. “My God, it’s them!” Diana exclaimed. The girls couldn’t believe it either: “No way! They lived in your guest house?”

In 1986, River Phoenix aced his breakout starring role in Stand by Me, director Rob Reiner’s poignant coming-of-age film based on a story by Stephen King. At age 15, his emotionally charged performance reflected a depth and intensity that foreshadowed his short but acclaimed career. At age 12, Joaquin had started acting in commercials, and was beginning to land guest roles on such television series as Hill Street Blues.

Ultimately the most famous Phoenix — an actor whose peculiar behavior often played out on late-night talk shows — the younger brother would later have audiences cheering as Johnny Cash in Walk the Line and shivering as a makeup-caked maniac in Joker.

After changing their last name, the Phoenix family had indeed gone to Hollywood to see if their children could find success in show business. After some lean years — at one point they lived in their car — the boys were stars. Who would have thought?

Well, who other than Alfonso Sainz? That’s why it’s a bittersweet memory for Diana, who couldn’t celebrate the news in person with her father, who was battling stomach cancer in Spain. “I called my dad and he literally almost cried,” she says. “He kept saying: ‘They made it.’”

Though his chances for survival were slim, Sainz — who remarried and continued his medical practice in Brevard County — went into remission following chemotherapy and other leading-edge treatments and lived to see the Phoenix siblings on the big screen.

Once he became a star and commanded more than $1 million per film, River bought a rural homestead for his family in Micanopy. River and Rain, as they had as children, began performing music together at clubs around the University of Florida in nearby Gainesville.

Their move back to Florida came, in part, to help River escape the drug culture in which he had immersed himself, first as research for 1991’s My Own Private Idaho, in which he played a gay street hustler. But his drug use didn’t end when shooting on the avant-garde film ended.

On Halloween night, 1993, River was back in Hollywood taking a short break from work on a new film, Dark Blood. While partying at the Viper Room, owned in part by fellow actor Johnny Depp, a musician from a well-known band gave River a drink containing lethal amounts of heroin and cocaine — commonly known as a speedball.

Rain and Joaquin, who were visiting, witnessed their brother being shoved out the door and convulsing on the street until his heart stopped. His death at age 23 was ruled accidental.

River’s ashes were spread during a private ceremony in Micanopy. From a distance, the Sainz family mourned the gifted boy they’d taken into their home and hearts. “When my dad found out he was devastated,” Diana remembers. “He saw so much talent in that kid and believed so much in him. He was saddened at the way it happened — and it has happened to so many.”

Sainz, writing a column for Florida Today in Brevard County following the tragedy, recalled his first meeting with River and Rain in Caracas: “The image of the two youngsters, with the pure innocence and clarity of song, will always remain in my heart. I cry for a return to their lost childhood. I only wish I could have had more influence.”

In 2013, Sainz’s cancer returned. With the time he had left, he reunited in Winter Park to make new music with another successful artist whose career he had helped to nurture, Tim Coons. But his time in the limelight had passed and his illness was progressing.

On April 17, 2014, The Singing Doctor died in his vacation home in Rockledge at age 71. Coons was with him to remember the good times spent together: “We were laughing — everybody else was crying, but we were laughing.”

Regarding Sainz’s importance as a musician, the Spanish edition of Rolling Stone ran a full-page obituary and photo. His former hometown newspaper, the Orlando Sentinel, wrote: “In one lifetime, Alfonso Sainz had mastered two worlds — music and medicine.”

After nine years, her father’s loss remains fresh and heart-wrenching for Diana: “My father had compassion. He had a heart. He was just a very giving person.” The Phoenix family would certainly attest to that.

Beatlemania and the Battle for Racial Justice in Florida

In 1964, the Beatles spent more time in Florida — nearly two weeks — than anywhere else in North America. Their second Ed Sullivan Show appearance, live from Miami Beach in February 1964, afforded them time to soak in the sunny beaches, magnificent homes and extravagant yachts.

They were back in September of that year to play a concert at the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, where they managed to thrill a packed stadium and strike a powerful blow against racial discrimination even as a pitched battle for civil rights raged throughout the region.

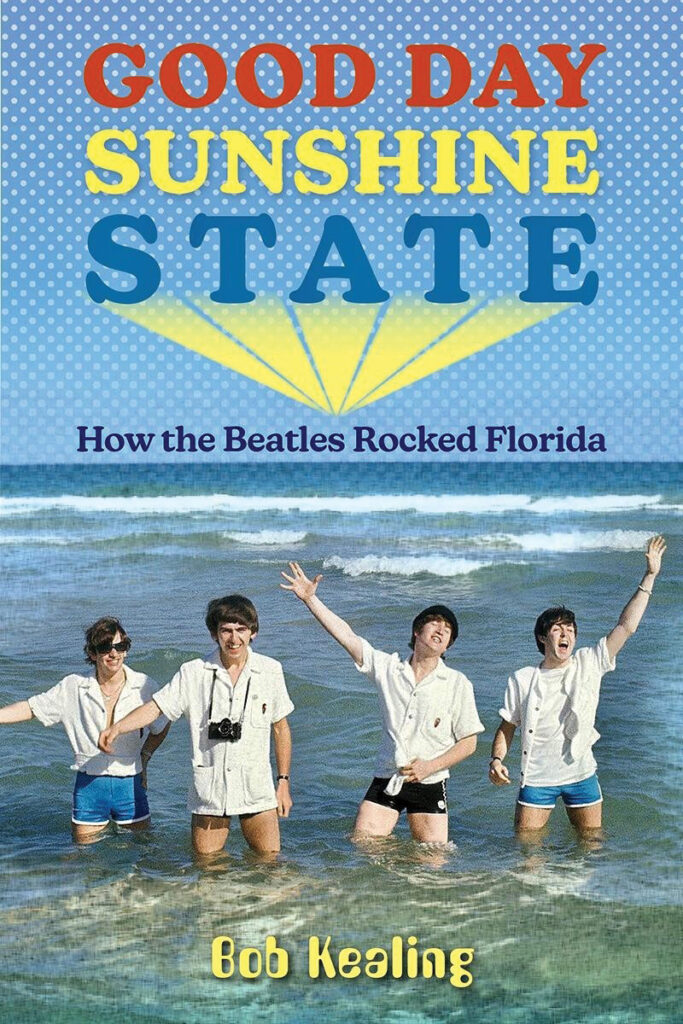

The Fab Four’s adventures in paradise are explored in Bob Kealing’s new book, Good Day Sunshine State: How the Beatles Rocked Florida (University Press of Florida).

Of special historic significance is the concert at the Gator Bowl. The Beatles — who had been unexpectedly diverted to Key West as Hurricane Dora passed over Northeast Florida — made it known just days before the concert that they would not play for segregated audiences.

That wasn’t welcome news to officials in Jacksonville, who enforced a policy of segregation in municipal facilities. The city relented just hours before the show was to go on. (The band’s opening act, The Exciters, became the first Black musicians to perform at the Gator Bowl.)

Kealing deftly juxtaposes the legendary concert with protests just months earlier in nearby St. Augustine, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. brought his “nonviolent army” to rally national support for passage of the federal Civil Rights Act.

Brutal attacks on protesters — and the arrest of King, who was held in the Duval County Jail in Jacksonville — garnered substantial media attention and may have hastened the act’s passage just 17 days later.

In writing Good Day Sunshine State, Kealing — a dogged researcher and a gifted storyteller — conducted more than 30 primary-source interviews and was given access to letters and memorabilia from the Beatles themselves.

The book recounts the experiences of journalists, fellow musicians and everyday people who encountered John, Paul, George and Ringo. The four lads from Liverpool could have had no clue how much they would change the world of music — and the world in general — in the decades to come.

Good Day Sunshine State: How the Beatles Rocked Florida is a highly readable and even important book — a must for fans of the band’s music as well as those interested in the social history of Florida. It’s available at bookstores and through online booksellers such as Amazon.

—Randy Noles