PHOTOGRAPHY BY CARLOS AMOEDO

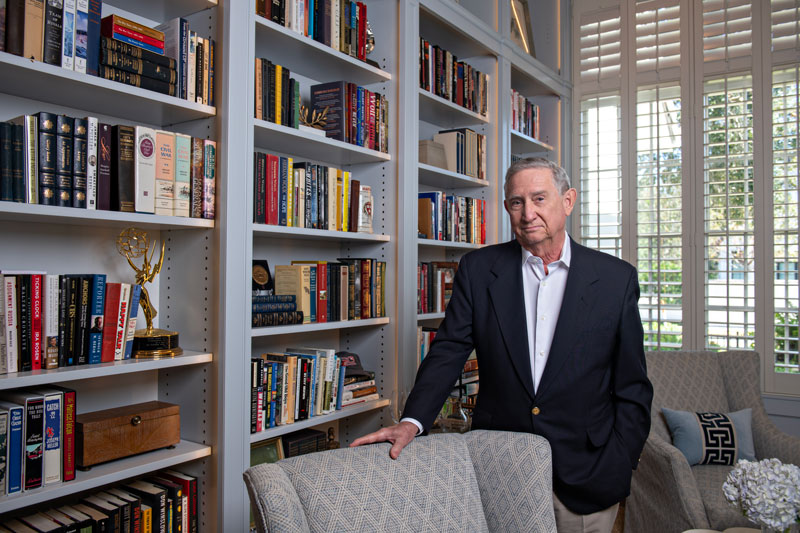

Lounging in the floor-to-ceiling library of his Winter Park home, sharing an easy chair with his kinetic Havanese puppy, Gracie, retired CBS News correspondent Jim Stewart leans in toward an inquiring reporter and confides: “I’m losing my hearing quickly. I had hearing aids. Gracie ate ’em four days ago.”

Then, in an instant, decades of obsessive devotion to fact-based reporting compels Stewart to correct the record. “She didn’t swallow,” he clarifies. “She just chewed ’em apart.”

Stewart, 76, and his wife, Jo, 68, a retired banking executive, moved to Winter Park in 2020 from Sandestin, a golf and beach resort area in the Florida Panhandle. It was their first stop following the end of Stewart’s distinguished 27-year career as a correspondent for the CBS Evening News. He was also a regular contributor to 60 Minutes II.

“There were just too many tourists and too many hurricanes in that part of Florida,” says Stewart, who was obliged to stay put because his elderly mother lived in a nearby assisted-living facility. As it turned out, Stewart’s mother ended up living for another decade and passed away just prior to her 100th birthday.

With no more familial ties to Sandestin, Stewart says that Jo — who had built a successful second career selling luxury real estate — wasted little time in arranging for a move further south.

Recalls Stewart: “I came home from playing golf one afternoon and she said, ‘I’ve sold the house, the packers will be here next week.’”

There was, after all, no reason to delay. The savvy Stewarts — who could have chosen to live anywhere — had spent considerable time vetting various destinations and had made up their minds.

“We went to quite a few other places that were either too crowded, too Florida, too Georgia, too much this or that,” notes Stewart. Proximity to first-class healthcare and a sophisticated college-town vibe, among other factors, weighed heavily in favor of Winter Park.

Adds Stewart: “Of course, we liked the old oak trees, we liked the brick-paved streets, and my wife — being a pretty darn good judge of real estate — saw this as a place where you cannot lose money.”

So, just like that, Winter Parkers had a another famous neighbor, albeit an unpretentious one who politely forbade Winter Park Magazine’s photographer from using his Emmy Awards as props and declined even to pose next to them.

Although it took a year of renovations to get the house in shape, Stewart says he offered very little input during the process.

“My wife designed everything in the house,” he says. “I told her the only thing I wanted was a library where I could get all my books in one place. I got most of ’em here. There’s still a bunch upstairs.”

THE TERRORISM BEAT

Even the most casual longtime newsies will instantly recognize Stewart’s muted Alabama twang — unusual for broadcasters, most of whom adopt a linguistically neutral style of delivery — and his distinctive visage, which he describes as “a face for radio.”

Indeed, with his slightly tilted head, quizzically furrowed brow, moderately protuberant ears and the ever-present hint of a twinkle in his eye, Stewart resembles an uber-vigilant elf on the shelf.

But the best reporters aren’t necessarily matinee idols. And Stewart, who upon his retirement was described as “a highly intelligent, eminently fair and doggedly determined reporter” by Sean McManus, president of CBS News and Sports, was inarguably one of the best.

Working out of the Tiffany Network’s Washington, D.C., bureau, he covered the Justice Department, the FBI and the CIA — beats that took on added gravity and visibility following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

That infamous morning, Stewart recalls, he was making his daily phone rounds of contacts when a senior FBI official on the other end of the line said, “My God! What was that?” Stewart turned on his TV and saw smoke billowing from the windows of the World Trade Center’s North Tower.

Both assumed that an errant small plane had struck the iconic building. Then, 17 minutes later, another aircraft slammed into the South Tower. “Al-Qaeda,” said the horrified official — which didn’t surprise Stewart.

“Everybody I’d been hanging around with in Washington had been singing the same song for months,” he says more than two decades later. “They’re coming if they’re not already here. It’s fair to say people in government knew. But it’s not something 60 Minutes is going to do a story on, saying, ‘Something may happen.’ It’s not their style.”

Stewart notched several high-profile exclusives during the ensuing months, including reports on the role of accused “20th hijacker” Zacarias Moussaoui and the FBI investigation of a terrorist cell in Lackawanna, New York, the members of which had attended an Al-Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan prior to the strikes on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center.

He also reported on the Gulf War, U.S. humanitarian and military missions in Somalia and Haiti, Hurricane Andrew in South Florida, the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City and the Centennial Olympic Park bombing in Atlanta.

Among Stewart’s many scoops: In 1996 he broke the news that the FBI was about to arrest a former mathematics professor named Ted Kaczynski, who was suspected (and later convicted) of being the Unabomber.

Although Stewart had the goods, he held the story to ensure that the raid on Kaczynski’s cabin in rural Montana would be a surprise. Not that he didn’t sweat it out until Kaczynski was in cuffs.

“I had a good story,” he recalls. “I was afraid I might lose it.” The FBI later praised Stewart and CBS for acting “in a memorably responsible manner.”

Delaying the immediate gratification of breaking a major news story out of deference to the FBI goes to the heart of Stewart’s professional modus operandi: the care and feeding of sources and the nurturing of mutual trust and respect.

“You have to understand the culture of the people you’re covering,” he says. “I went to their holiday parties and retirement and promotion parties. I would celebrate those moments with them. Gossip with them.”

Adds Stewart: “If you were lucky, you got their phone numbers so when there was blood on the sidewalk and you were about to go live to a national audience, you could call a secret number and say, ‘Jack, what the hell is going on?’”

SOUTHERN EXPOSURE

Among books, framed photos and objects d’art on Stewart’s soaring shelves are four gleaming gold Emmy Awards. He also picked up four Pulitzer Prize nominations for his newspaper work before TV came calling.

For Stewart — who was born in Dothan but grew up in Montgomery, Alabama — the journalism bug bit early. It happened, he recalls, when he was 8 or 9 years old and his cousin Paul, a rookie sportswriter, took him to a minor-league Birmingham Barons baseball game.

Cousin Paul flashed his press credentials and the two were waved through to the catbird seats in the press box, where free hot dogs and soft drinks awaited.

“I thought, ‘You know, this is a pretty nice deal,’” says Stewart. It proved to be a very nice deal indeed for his cousin and role model, the late Paul Hemphill, who would earn the moniker “the Jimmy Breslin of the South” for his books about football, country music, stock-car racing and blue highways strewn with unforgettable characters.

Except for one not-so-shining moment, sportswriting wasn’t a stop on Stewart’s media odyssey, which he began as a police reporter for the Montgomery Advertiser, his hometown newspaper.

He had grown up reading the Advertiser and sometimes bought his own copy of The New York Times as an added sensory treat, drawn as he was to the feel of newsprint and the ambrosia of printer’s ink. Naturally, the budding newsroom junkie majored in journalism at Auburn University.

Recalls Stewart: “I was sitting in class and the professor said he’d heard gossip that UPI (United Press International) had fired all its staff in Alabama and brought in a new bureau chief, and he was hiring. Serendipity!”

He borrowed a friend’s car and drove to Montgomery, nearly 60 miles to the southwest, where he was hired by UPI to work weekends and later the noon to 9 p.m. shift on weekdays. He adjusted his schedule at Auburn to include as many 7 a.m. classes as possible so he would have at least an hour to get to work on time.

It was usually at least 10 p.m. before he returned to campus, where he would study or write papers into the wee hours before another 15- or 16-hour day dawned. “Looking back now, I don’t know how I did that,” says Stewart of his senior year.

Stewart’s assignments would include coverage of the civil rights movement and the presidential ambitions of Alabama Governor George Wallace. But his first significant story involved a personal hero, Chief Judge Frank M. Johnson of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama.

“Anything [Johnson] opined about became instant news around the country,” Stewart says. “He came out with a big decision one weekend. I ran down to the courthouse to look at this long decision. I didn’t have a clue what I was looking for.”

Much to Stewart’s surprise, Johnson’s secretary invited the baffled rookie into the judge’s chambers, where he found himself in the presence of the man whose landmark civil rights rulings helped end segregation and the disenfranchisement of African Americans in the South.

Recalls Stewart: “Judge Johnson said, ‘Let me explain it to you in simple terms.’ He did, and I got the story — and I got it right.”

Not destined for the scrapbook — since it produced no scraps — was Stewart’s first sports assignment for UPI: a home basketball game between Auburn and Kentucky. He was asked to fill in at the last minute for a more experienced but ailing reporter based in Atlanta.

“I got there, and they ushered me down to the floor to a little table and chair,” says Stewart. “You’re right there, the game’s right in front of you. It goes by so quick. The final buzzer went off, then I picked up the phone and called Atlanta. I said, ‘Auburn won, 58–55!’ They said, ‘Yeah. And?’ I said, ‘Well, it was a hell of a game!’ I thought they just wanted the score.”

Adds Stewart: “Atlanta never asked that kid reporter in Montgomery to ever cover another sporting event.”

After graduating from Auburn in 1969 with a fistful of UPI clips, Stewart — who had participated in the campus ROTC program — was obligated to serve two years of active duty in the Army. As a first lieutenant, he was sent to Europe and Panama before leading a platoon in South Vietnam.

“If you were lucky, you got their phone numbers so when there was blood on the sidewalk and you were about to go live to a national audience, you could call a secret number and say, ‘Jack, what the hell is going on?'”

Stewart would return to that war-ravaged country at the behest of the morning Atlanta Constitution, where he landed his first newspaper job after mustering out in 1972.

“About three months in, the editor tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘How would you like to go back to Vietnam?’ I almost said, ‘What in the hell are you talkin’ about?’”

But the offer was to return as a columnist, not a reporter, which Stewart found appealing. “A one-man bureau cannot cover the daily goings on of war,” he says. “But you can come up with three columns a week giving a sense of the flow of events.”

After the war ended, Stewart moved into editorial management roles as special assignments editor then assistant managing editor in charge of news operations at the Constitution and the Atlanta Journal, which merged staffs in 1982 and emerged as the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2001.

In 1985, Stewart joined Cox Newspapers as national security correspondent in Washington and earned four Pulitzer Prize nominations for his work on that beat. As an old-school newshound — a proverbial workhorse, not a showhorse — he certainly never expected to become a TV glamor boy.

Of course, the glamor boy part never happened. But the TV part did — much to Stewart’s amazement.

THE TIFFANY NETWORK

When CBS called in 1990, the wordsmith at first had none with which to reply. “I was stunned,” Stewart says. “Honest to God, I went through the first conversation and part of the second one believing that they were asking me to be a producer, which would have made more sense from my perspective.”

Stewart knew that he didn’t look — or sound — like most TV reporters. But, as it happened, his stern, gimlet-eyed demeanor on camera was well-suited to the gravity of the subject matter that he covered.

Granted, there were performance issues to overcome. Says Stewart: “The president of CBS News at the time was very blunt. ‘You look like a deer caught in the spotlight, boy.’ I said, ‘I’m workin’ hard to get over that,’ and he said, ‘Well, keep workin’.”

And that’s exactly what he did for the next 27 years. His accent, over time, smoothed out like barrel-aged bourbon, and his presentation became polished but never showy.

Then, in 2007, shortly after turning 60, Stewart retired from CBS. That’s early for anyone, but especially for a journalist who’s still at the top of his game. Pentagon correspondent David Martin is still chasing down tips at age 69. Ditto Scott Pelley (65), Bill Whitaker (71) and Lesley Stahl (80).

“The war in Ukraine gives me regrets every day. It’s the first [morally] unambiguous war we’ve seen since World War II. But at 76 you don’t run as fast as you used to, and believe me, there’s still a certain amount of physical activity required to cover a war.”

Sure, TV is increasingly a young person’s medium, and the journalists listed — all of whom remain among the best in the business — are chronologically more the exception than the rule. But Stewart was unquestionably every bit as good, and could have had an even longer career.

So why step aside? Call it battle fatigue. “I had done nothing but terrorism since I took over the FBI beat in 1993,” Stewart says. “Waco, Ruby Ridge, Oklahoma City. Then the world’s attention pivoted to Osama Bin Laden and the whole string of events that led to 9/11.”

In 2006, Stewart’s three-year “personal services contract” with CBS, standard in TV news, was up for renewal. “I just did not want to do another three years,” he says. “Was it hard to walk away from a really nice salary? Yes. Was it hard to walk away from the excitement of being in the center of things in Washington? Yes. But my wife and I had always planned a second career in Florida. It was time.”

In Sandestin, Jo slid into her second career in a New York minute. “She specialized in high-end real estate and dominated the market,” Stewart says. “Meanwhile, I did very selfish things. Many days, I just started reading a book and finished it. I played a lot of golf. We traveled extensively.”

His own second career — as if the first one hadn’t been challenging enough — was proving elusive. Well, who better than a legendary reporter — who was a 1981 Nieman Fellow at Harvard University along with his other professional honors — to teach journalism?

“When I first got to the panhandle some people at the local community college wondered if I’d be interested,” he says. “I said no. I don’t have the patience. I had a friend who taught after he left CBS. He quit after two or three years because he couldn’t stand it. You have to jump through so many hoops with the faculty to come up with curriculum that meets their criteria.”

OK, then, how about writing his memoirs? “In my interview for the Nieman Fellowship, a professor asked what I wrote when I wrote simply for pleasure and not on deadline,” he recalls. “I said, ‘I don’t write for pleasure, I write for money.’”

Stewart did, in fact, come up with a way to write for money — indirectly — that he thought would be tolerable if not an actual pleasure.

“I naively thought I could be of assistance to Jo in the real estate business, that I could write the property descriptions, I could do the advertising,” he says. “We were dabbling in rental properties and I would manage those and oversee their maintenance.”

Jo fired her well-meaning husband after he ordered that a house be power washed before it was properly prepped. “The water went through one end and out the other,” says Stewart. “So pathetic. I just wasn’t very good at it.”

Stewart never found a second career — fate found it for him. There is something besides reporting and writing that he’s very good at it, but it never crossed his mind as he searched for something to occupy his time that didn’t involve the use of machinery like power washers.

It turned out that the man who once kept the country abreast of terrorist activity was very good at cooking. How good? He once prepared a barbecue dinner for Julia Child and scored a rave review. “Delicious!” he chirps in a tremulous, high-pitched warble that echoes Dan Aykroyd’s impersonation of Child in the classic Saturday Night Live “French Chef” skit.

Stewart’s close encounter with Child came in 1981, during his Nieman Fellowship in Boston, when Child and her husband Paul lived near the Nieman House where Jim and Jo were ensconced.

“We decided to do a Southern barbecue for the class and staff — chicken, baby-back ribs and potato salad,” Stewart says. “I went to buy the baby-back ribs and couldn’t find them anywhere. The curator of the program said to ask Julia, who said, ‘Don’t worry — I’ll take care of this!’”

Child called her personal butcher and made sure that Stewart got what he needed for the barbecue. The next day she joined the party and delivered a five-star verdict on the feast: “Top that story!” exclaimed the renowned author, cooking teacher and TV personality.

The self-taught Stewart was particularly giddy at getting kudos from a celebrity chef. “My mother couldn’t scramble an egg,” he says. “I learned how to cook out of self-preservation and found that I just truly enjoyed it. I do all the cooking here. I buy all the food and do all the cooking and all the kitchen cleanup.”

Later, settling into Sandestin, Stewart became aware of elderly neighbors, many afflicted with terminal illnesses, who could benefit physically and psychically from a home-cooked meal. So, on his own, he began preparing and delivering cuisine that he describes as “comfort soul food.”

“I still watch the evening news, but it’s more out of curiosity to see who has survived and how they handle a particular story. I never watch it anymore to fulfill my mantra as a journalist: ‘Tell me something I don’t know.”

Among the most popular dishes on Stewart’s menu: Greek lemon soup (facing page), chicken and dumplings, pasta with sweet Italian sausage, seafood gumbo and Brunswick stew. “I could turn those out in mass quickly,” he says. “I could do it in my sleep.”

Because he derived great satisfaction from cooking and sharing, Stewart hoped for opportunities to continue doing so in Winter Park. But because he and Jo arrived at the height of the pandemic, when vulnerable populations were in isolation, the activity mostly fell by the wayside.

These days, Stewart plays golf, perfects recipes and watches history unfold from a safe distance. But does he ever wish he was out there reporting it? Sure, he admits, of course he does.

“The war in Ukraine gives me regrets every day,” he says. “It’s the first [morally] unambiguous war we’ve seen since World War II. But at 76 you don’t run as fast as you used to, and believe me, there’s still a certain amount of physical activity required to cover a war.”

NEWS DUMBS DOWN

As for today’s media landscape, Stewart is astonished — and not in a good way — about how much has changed. He holds social media in particular contempt and eschews having a personal presence on any of the platforms from which so many people consume their news — fake and otherwise — these days.

Because of social media, he says, anybody can pretend to be a journalist, regardless of whether they have the requisite qualifications, “and tell any lie they want to tell” because many people — as anyone who engages on Facebook can readily attest — lack the critical thinking skills to discern fact from fiction.

“Every old codger is going to say it’s not the same as it was when I was there,” Stewart admits. But he laments the fact that networks no longer hired people who, like him, had been totally immersed in the subjects they were expected to cover.

Nowadays, he says, networks hire younger people — generalists, not subject-matter experts — who can think on their feet and look good on TV. Some, he says, are “extraordinarily talented in stressful situations,” but many lack the depth of knowledge that comes only with decades of experience.

“I still watch the evening news, but it’s more out of curiosity to see who has survived and how they handle a particular story,” Stewart says. “I never watch it anymore to fulfill my mantra as a journalist: ‘Tell me something I don’t know.’”

The veteran newsman still has The New York Times — the print version — delivered to his doorstep. And every day he reads Politico, the Washington Post and other news sources via apps on his smartphone. He notes: “It’s not bragging to say that it’s hard to tell me something I don’t know.”

Here’s something Jim Stewart doesn’t know: In the history of Auburn-Kentucky basketball games, there’s never been a 58–55 result. He might be thinking of a 74–73 Auburn victory over No. 8-ranked Kentucky in the Tigers’ gym in January 1968.

Stewart can be forgiven for not remembering the score of a game he never wrote about. It turned out the kid who went from the press box to the Pentagon had bigger fish to fry. Sportswriting’s negligible loss was TV journalism’s immense gain.

JIM STEWART’S AVGOLEMONO

GREEK LEMON CHICKEN SOUP

“This was the favorite of COVID-19 patients, all others suffering from respiratory illnesses and my wife at any time. Two steps are important to note. First is the ratio of liquid to rice or orzo (rice-shaped pasta) to get the right consistency. Second is the necessity to temper your egg yolk and lemon juice with a ladle of hot soup before adding the mixture to the soup pot.”

—Jim Stewart

Ingredients

6 cups chicken stock, or six cups water fortified with two tablespoons of Maggi or Herb Ox chicken stock powder dissolved

2 bay leaves

2 chicken breasts, bone-in, skin-on

3 egg yolks

Juice from one medium-sized lemon

2 lemon zest strips finely minced

1 medium onion, diced

2 celery stalks, diced

1 small carrot, grated finely

1/2 cup long-grain uncooked white rice (orzo will do as well, but add a bit more.)

2 tablespoons butter

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

Salt and pepper to taste

Directions

- Bring stock with bay leaves to a low boil. Add chicken breasts and cover. Cook approximately 15–20 minutes until chicken is done. Remove to a colander and reduce heat to a simmer.

- With a fork, lightly beat the egg yolks, lemon juice and zest until incorporated. Add two to three small ladles of the stock, one at a time, to the egg mixture, stirring constantly.

- When the mixture has been tempered, add it to the soup pot. The point is not to curdle the yolks with too much hot liquid to start.

- Now add all the rest to the pot: onion, celery, carrot and rice. Bring to a low boil, then immediately lower to simmer. Cover and let the rice do its thing.

- Meanwhile, chop the chicken into bite size portions. Add it to the pot, cover again and let simmer for approximately 30–45 minutes.

- The finished product is a thick, almost stand-up-spoon soup that’s finished with butter, parsley and salt and pepper. Taste frequently at this stage, adjust seasonings and maybe add more butter. Serve with toasted ciabatta or crackers.