Jon Gnagy was a TV star before Milton Berle, before Lucille Ball, before Kukla, Fran or Ollie. At the height of Gnagy’s popularity, Manhattan bartenders handed out paper and pencils to patrons who put down their martinis to sketch along with ‘’America’s Television Art Instructor.’’

Gnagy’s weekly, prime-time series, You Are an Artist, premiered on NBC radio’s newfangled television network in the fall of 1946. The first episode established a basic format that the goateed artist (didn’t all artists have goatees?) stuck with for more than a decade.

The camera would pan a charcoal drawing of basic geometric shapes to the strains of Strauss’s ‘’Artist’s Life.’’ Then the personable Gnagy, usually wearing a plaid shirt and shown in glorious (well, grainy) black and white, would assure viewers that they could just as easily draw a log as fall off one.

“Friends, I’m here to prove to you that you can draw your way to fame,” said Gnagy (NAY-gee), who would then sketch some archetypically American scene — haystacks beneath a full moon, wild geese in flight, boys sledding down a snow-covered slope.

Kids at home — and more than a few adults — drew along with him as he confidently slashed a thick-tipped charcoal pencil across an oversized sheet of white paper, explaining every mark he made as he worked. In just 15 minutes, he created workmanlike images from a handful of strategically shaded geometric shapes.

Gnagy’s mantra: “Ball, cube, cylinder, cone. By using these four shapes, I can draw any picture I want. And so can you!” And Gnagy didn’t want to hear the excuse, “I can’t even draw a straight line.” Well, of course you can’t, he’d explain. Nobody can draw a straight line. That’s what rulers are used for.

Very few performers from TV’s earliest days are remembered at all. Gnagy, who died in 1981, is not only remembered — he’s beloved, respected and still marketable. To this day, Jon Gnagy “Learn to Draw” sets are sold by Martin F. Weber Co., a Philadelphia-based manufacturer of artist supplies.

The refreshingly low-tech contents still include four art pencils, three sketching chalks, a kneaded eraser, a blending stomp, a sandpaper sharpener and a laptop drawing board as well as sketch paper and Gnagy’s classic 64-page book, Learn to Draw. (There are likewise two Gnagy-branded sets for would-be painters).

And a hardcover biography, Jon Gnagy: America’s Art Teacher, was self-published this year by Charles M. Province, a California-based military veteran and the author of several books about General George S. Patton. The book combines a narrative about Gnagy’s life with appreciations from present-day artists and articles written during his lifetime by and about Gnagy.

Province is also founder of the fledgling Jon Gnagy Society, which he hopes will encourage interest in the work of the trailblazing creator and marketeer who was Bob Ross before there was a Bob Ross. “Gnagy was the first and he was the best,” says Province, who adds that he watched the artist’s show in the late 1940s. “He showed everyone how it should be done.”

An Accomplished Daughter

Of course, no one appreciates Gnagy’s importance more than Polly Gnagy Seymour, 93, a beloved Winter Parker and wife of the late Thaddeus Seymour, president of Rollins College from 1978 to 1990. The ebullient educator, a community giant both literally and figuratively, died in 2019. But Polly remains sharp, funny and engaged.

“I felt as though I knew my father well, but of course I mainly knew him as a father,” she says. “His great days were when he was at the top of his health, his energy and his talent — he was completely committed to his television show and his vision. I was busy with my own life and I didn’t always understand that at the time.”

Being the wife of one high-profile man and the daughter of another, Polly has nonetheless built quite a legacy of her own. When the Seymours arrived at Rollins, she quietly went to work sprucing up the threadbare campus and making it a more welcoming place for visitors and students alike.

She haunted used furniture stores to find chairs, couches and tables to adorn the neglected lounges in the residence halls. She also reorganized the food service in what was then called The Beanery, improving the ambiance, the food and the service.

And when trustees or donors were entertained, it was Polly who usually did the cooking and serving at the couple’s modest home on Lakewood Drive. From ice cream socials for honor students to lavish dinners for VIPs, she impressed everyone with her sophisticated charm and her droll sense of humor.

Following her husband’s retirement in 1990, Polly’s behind-the-scenes style proved just as effective in the broader community. In 1993, the Seymours helped launch Habitat for Humanity of Winter Park-Maitland, and during construction of the eight homes sponsored by the college, the former first lady provided lunch for workers every Saturday.

She also increased her involvement with the Winter Park Library — she had previously served as president of its board of trustees and chair of its annual book sale — and conceptualized the New Leaf Bookstore (now the Polly Seymour New Leaf Bookstore), which opened its doors in 1995. Since then, the bookstore has raised more than $1.3 million to support the library.

In 1997, the Seymours were named Citizens of the Year by the Winter Park Chamber of Commerce. And in 2017, Polly was honored by the Florida Library Association with its Outstanding Member Award.

Still, in the mid-1980s, she also became determined to increase the profile of her father, who had died in 1981. Her home, after all, was crammed with artwork that she had retrieved following the subsequent death of her mother, Mary Jo Hinton — a talented artist and calligrapher in her own right — who had survived Gnagy by only a year. Shouldn’t these paintings and drawings be seen?

She had a series of four lithographs of twisted desert flora, loose-line drawings of New York’s Central Park, and a minutely detailed oil of a blacksmith’s hammer and anvil that was her father’s favorite. She had two oils, one dominated by an ear of corn, the other by a monarch butterfly, from a never-completed Cycle of Life series.

She had soothing watercolor landscapes and an intense, pop-art like tempera painting of a potted palm. She had the palette-knife painting of a vase of flowers that her father had completed for the Federal Communications Commission to test the relative merits of CBS and RCA’s color-TV systems.

Hanging in a frame that produces an aquarium effect was a painting Gnagy created to illustrate a first-person fishing story for True magazine in 1959. A lake-bottom view of fly fishing, it shows a swarm of fish, led by a golden grouper, frenetically twisting toward Gnagy’s lures.

Polly had nothing of her father’s earliest work and few examples of his commercial illustrations from the 1930s. Nor, regrettably, did she have much of the work for which he is best known: the TV sketches. She said her father was generous to a fault — he usually gave away the drawings he did on camera to fans or studio hands.

Each piece — some 200 individual works, plus prints — was named and described by size and condition in preparation for an exhibition, The World of John Gnagy, at the Maitland Art Center. ‘’I feel that I owe this to my father,” Polly said at the time. “I really think he was good, and I think he was a fascinating man at a fascinating time.”

In a 1986 promotional video made about the exhibition, Polly strolls through the art center’s studios and affectionately describes the variety of works on display, from finely wrought scratchboard images of fish to lonely but vivid farm landscapes.

There’s also a strange oil painting of Louis Armstrong, who had recently died, playing his trumpet in heaven — a work Polly describes as “indicating my father’s particular interest in the psychosymbolic.”

Then she points out her personal favorite — a work she still owns. It’s a small oil painting, the prototype of a wine label that her father had designed, which shows lustrous grapes in the foreground, green vineyards fading into a horizon, the brilliant blue twilight embracing a mystically pale moon.

James “Gerry” Shepp, then the museum’s executive director, also appears on camera and marvels at the number of exhibition visitors who retain fond memories of watching Gnagy on TV and learning to draw from him. “People come in and say, ‘Wow! John Gnagy! I remember seeing him every Saturday morning,” says Shepp. “It makes you realize what a small world it is.”

The works in The World of Jon Gnagy spanned some 40 years and amply demonstrated that Gnagy was amazingly versatile. And for Polly, the project and the response to it was something of a revelation.

“One of the things I discovered was that a lot of people knew about my father, but they didn’t know he was my father, so in some ways it gave me a new identity in the community,” she now says. “I sold one painting, which more or less covered the cost of mounting the show. That, really, was more than I had ever hoped for.”

A Television Pioneer

Gnagy was born into a strict, righteous farming family in 1907. His trademark Vandyke beard was no arty, beatnik affectation but rather a gesture of respect for his Mennonite upbringing in Pretty Prairie, Kansas.

His parents, especially his father, an expert cabinetmaker, encouraged young Jon’s yen to draw and paint as long as he rendered barns and corn shocks and windswept prairie landscapes — images he later would share with millions of pupils.

Portraits were another matter — at portraits, his folks drew the line. Their Mennonite beliefs held that portraits were graven images, a form of idolatry. Wildlife and rustic scenes dominate Gnagy’s TV sketches and his fine-art works; people’s faces are rare.

At least, that’s how Gnagy told it. While the family was Mennonite, Polly’s daughter Liz Seymour, a writer who has researched the artist’s life, says that the Gnagys practiced a more worldly version of their religion and that her grandfather, who knew how to spin a compelling yarn, may have exaggerated their piety by engaging in “myth making.”

In any case, Gnagy left the farm at age 17 to move to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where the following year he became an artist — and, after just a year, the art director — at an advertising agency. He also met and married a talented young apprentice, Mary Jo, forming a union that would last for more than a half-century.

The couple then moved to Wichita, Kansas, and then to Kansas City, Kansas, where Gnagy continued to work in advertising. He also enrolled in the Kansas City Art Institute’s commercial art program, where he clashed with an instructor who criticized his self-taught methods but enjoyed the creative energy he absorbed from other students.

Gnagy never graduated, however. Instead, in 1931, he sent Mary Jo and their daughter Polly to live with Mary Jo’s family in Texas while he struck out for New York City to seek his fortune. The Depression was at its height, but so was Gnagy’s confidence. Before his $24 stake ran out, he finessed a freelance assignment from Alcoa for full-page ads that ran in the Saturday Evening Post and Fortune.

Soon, Gnagy brought his wife and daughter to New York — to a small apartment in Pelham, near New Rochelle — where they bore a son, Steven (who died in 1997). But at a time when more than one-third of adults were unemployed, Gnagy soon found that his early freelance successes weren’t a harbinger of prosperity.

Unable to afford Gnagy’s commutes into Manhattan, the family moved to more economical quarters above a steam laundry in Flushing, Long Island. But there was no work to be found and the hustling that it took to make ends meet took its toll. In 1937, Gnagy suffered a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized for seven months.

The diagnosis was “dementia praecox,” a catch-all phrase then used to describe severe mental illness — including what medical science now recognizes as schizophrenia — and treated with electroshock therapy.

Yet, despite the crude medical regimen, Gnagy recovered and was released. Most likely, then, he had experienced an episode of severe anxiety or perhaps manic depression that had resolved itself over time.

Shortly thereafter, Gnagy managed to land an art director position at an ad agency in Philadelphia. He did well enough to buy a home in sophisticated New Hope, a culture-rich haven for artists and intellectuals about 30 miles north of the City of Brotherly Love.

During his daily round trip into the city via a commuter train, Gnagy later wrote, he read books about art, theater and philosophy “in an effort to obtain the requisite know-how and to find if I could that elusive, intangible key to the aesthetics I sought.”

Gnagy also started a small school and gradually perfected his teaching methods. Like Paul Cézanne, one of his inspirations, Gnagy emphasized the basic shapes — ball, cube, cylinder, cone — and incorporated them into a simple, easy-to-follow teaching technique.

‘’The classes were very successful,’’ Polly says. ‘’As soon as he realized he could teach, he also realized there would soon be a wider medium available in which he could do the same thing.’’

The medium was television, a demonstration of which had captured Gnagy’s fancy at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. America’s entry into World War II, coincidentally, allowed him to hone the skills he would need to succeed on the small screen.

During the war, Gnagy taught camouflage techniques for the U.S. Army as an art director for the War Services Committee, which was responsible for posters displayed in production plants. Through the development and delivery of training sessions, he became a polished audiovisual educator.

After the war Gnagy hit the lecture circuit, where he practiced drawing demonstrations in front of student groups and club luncheons. He also lectured on such subjects as “The Science of Color and Harmony” and “The Psychology of Color Vision.”

When NBC finally got around to erecting a 61-foot television broadcasting antenna atop the Empire State Building in May 1946, Gnagy was ready. “It was one of those wonderful combinations of the right person at the right place at the right time with the right characteristics,’’ says Polly.

Gnagy’s first TV appearance, a segment of a variety show called Radio City Matinee, earned him congratulations from NBC founder David Sarnoff and Vladimir Zworykin, the inventor of the television camera and the picture tube.

The comment Gnagy treasured most that historic day came from Warren Wade, the pioneering show’s production manager. “Jon, you were great,’’ Wade said. Then, coining a phrase that has become a cliche, he added, ‘’Your show is pure television.’’

In addition to Gnagy, Radio City Matinee included a comedian, a gossip commentator and a chef who presented the first-ever televised cooking demonstration — the progeny of which can be viewed, almost constantly, 70 years later. The show was seen by only about 200 TV viewers who lived within a 60-mile radius of the studio — but it was a start.

Three years later, there were roughly 11 million TV sets across the country and nearly all of them, at some point, had tuned in to Gnagy’s 15-minute stand-alone program, You Are an Artist, which aired at 11:45 a.m. on Sundays. Many viewers, at Gnagy’s urging, had sent the network their own creations for him to critique.

The critics, in that simpler time, were kind. Gnagy’s “thoroughly engaging set-side manner” was praised by The New York Times, while the host’s low-key charisma and the show’s “air of authenticity” was lauded by TV Guide.

Kudos notwithstanding, NBC canceled You Are An Artist in 1949 and replaced it with The Mohawk Showroom, sponsored by the Mohawk Carpet Company and hosted by singer and bandleader Morton Downey — whose son would gain fame in the 1980s for his lowbrow televised screamfest.

Gnagy, however, became even more visible without network affiliation. He and William Einhorn — advertising manager of Arthur Brown & Company, a now-defunct New York City-based art-supply distributor — co-produced a new show, Learn to Draw, which soon blanketed the country via syndication and cemented Gnagy’s celebrity.

Learn to Draw, which cost about $450 per episode to produce, was offered to individual stations free of charge. But Gnagy — who might rightly be credited with creating the first infomercials — was able to promote the sale of his drawing kits to some 60 million households every week.

“Remember folks,” Gnagy would say, “you can buy my books and kits at any quality art supply store near you.” At least 15 million kits had been sold by the mid-1980s.

“Not only did Jon invent the technique of televised art instruction, but he also invented the art of direct television marketing strategies,” says Province, the artist’s biographer. “He was not just a great artist, nor was he just a great art teacher. He was an advertising genius.”

As always, when a creator — regardless of the genre — becomes broadly popular, certain circles in academia protest that anyone so beloved by the great unwashed must be some sort of hack. That was the case with Gnagy in 1951, when members of the Museum of Modern Art’s committee on art education sent a critical letter to The New York Times.

They wrote: “The use of superficial tricks and formulas found in the Jon Gnagy type of program is destructive to the creative and mental growth of children and they perpetuate outmoded and authoritarian concepts of education.”

Instead of following rigid guidelines, the educators contended, a child should be encouraged to “use his or her own experience, and to explore new media and techniques.”

Gnagy’s response was muted. He defended his methods, saying that the idea of art being based on a handful of geometric shapes could be credited to Cézanne and other post-impressionists. As a practical matter, he added: “If someone will subsidize me for 15 minutes a week on television, I’ll be glad to teach sheer imagination. But there just aren’t enough people interested in such a show to make it financially feasible.”

Although Learn to Draw ceased production in 1960, previously taped episodes remained in syndication until 1971. By then, half-hours were the smallest increment a station would run, and Gnagy’s show remained black-and-white after color TV had become ubiquitous.

Off and on for the rest of his life, Polly says, her father ‘’tried to perfect a technique that would permit him to do a half-hour show in color in a way that other people could follow with an acceptable result. And he never really got back into television.’’

Gnagy, in the meantime, had long since retreated permanently to Southern California, where he had set up a studio at Idyllwild, in the heart of the San Jacinto Mountains. There he painted — for the sheer pleasure it brought him — and offered art lessons at an adjacent café because he still loved to teach.

Liz, the eldest grandchild who now lives in Greensboro, North Carolina, remembers visiting Idyllwild as a girl and noting that her grandfather’s boots were almost entirely pink. Gnagy, it seems, had been pouring out pink paint and stomping the color-soaked surface as an artistic experiment of some sort. “Not everybody’s grandfather did things like that,” Liz notes.

Gnagy also spent considerable time fishing — his favorite pastime, next to drawing and painting — and accepted some professional commissions, including as an illustrator and editorial contributor to fishing magazines and other outdoors-oriented periodicals. He died of heart failure, at age 74, in 1981.

A Lasting Legacy

Gnagy’s legacy has continued through those who’ve had successful — even legendary — careers in art as well as through hobbyists who draw and paint only for relaxation.

The drawing kits don’t sell as well as they used to, but Polly say she still hears from fans. “I get emails a couple of times a year from people who remember my father and credit him with encouraging them to make art,” she says.

And she’s still learning new things about her father. The Province biography, for instance, included some of the illustrations Gnagy did for his high school yearbook in Hutchinson. “I had never seen them before,” she says. “They’re very good.”

Gnagy inspired future artists as diverse as Andy Warhol and former Orlando Sentinel cartoonist Jake Vest. Warhol once declared that Gnagy “taught me to draw. I watched his show every Saturday morning and I bought all his books.” Vest, now a teacher in Lake County, says Gnagy “is the reason I’m drawing trucks instead of drivin’ ’em. I didn’t know I could draw until he told me I could.’’

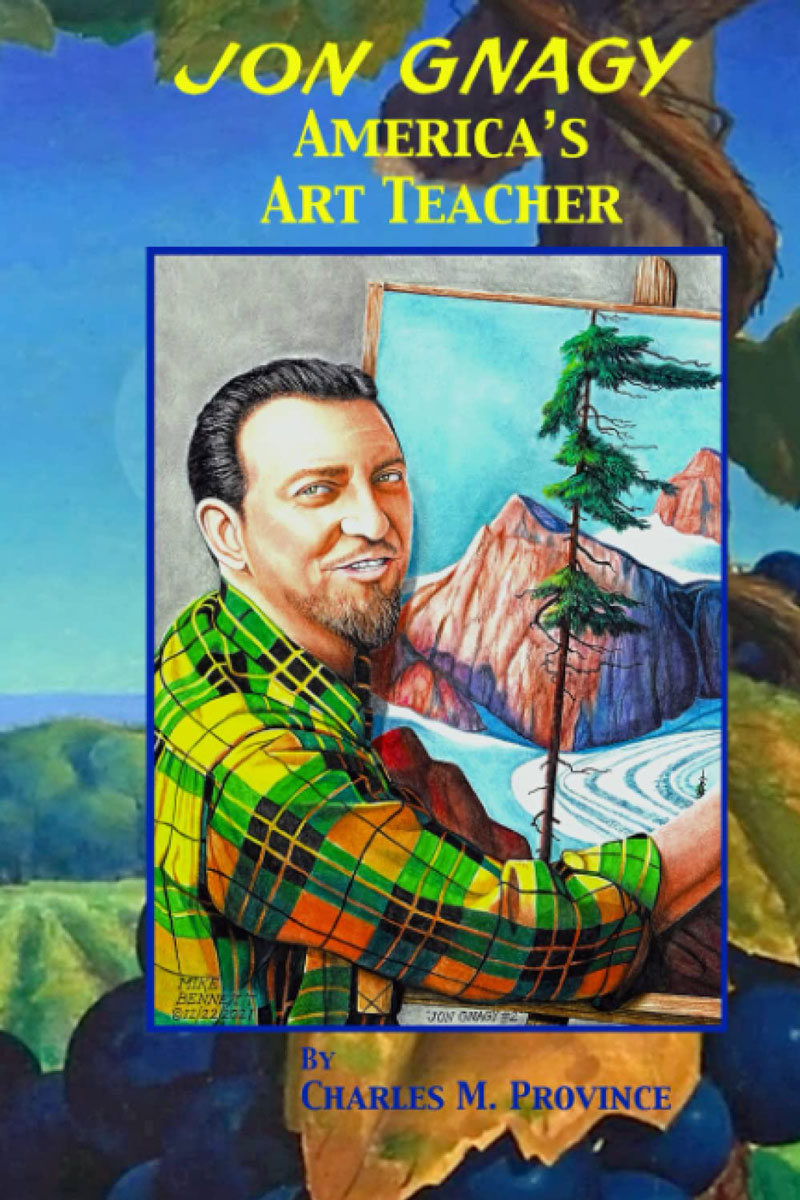

Two California artists, Mike Bennett and Henry Balzer, credit Gnagy’s influence for their careers and contributed chapters to Province’s book. Bennett, in fact, painted the cover in Gnagy’s style.

Polly, who now lives in Westminster Towers, certainly did her part to keep Gnagy’s name in the pop-culture consciousness. “I’m not really involved in promoting my father now,” she says. “I do enjoy hearing from people who say how much his show and his kits meant to them. Mostly I’m just passing along the artwork that I have to family and friends.”

Somehow, one expects that Jon Gnagy — who gave away much of his work to fans — would approve of that approach.

To learn more about Jon Gnagy, read Jon Gnagy: America’s Art Teacher, by Charles M. Province. (The cover features a painting of Gnagy by Mike Bennett, who rendered it in Gnagy’s style.) The 430-page book, a thorough biography filled with illustrations as well as tributes to Gnagy by other artists, can be ordered from booksellers such as Amazon or by visiting Province’s website, pattonhq.com. To find out more about the Jon Gnagy Society, visit pattonhq.com/gnagy.html.