After Amy Melder became a Christian at the age of 6, she set out to evangelize everyone she cared about. One of the names on the top of her list was a person whom she’d never actually met: Fred Rogers.

Amy was a frequent viewer of PBS’s Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and had formed a deep connection to the gentle host who made her feel “safe and accepted in his tiny staged living room.”

So she penned Rogers, who died in 2003, a letter to “make sure he knew he was going to heaven.” Within weeks, she received a lengthy response from a man who personally answered every piece of fan mail he received.

He thanked her for the colorful drawing she sent him, which “is special because you made it for me.” And then he addressed the matter that most concerned Amy:

“You told me that you have accepted Jesus as your Savior. It means a lot to me to know that. And, I appreciated the Scripture verse that you sent. I am an ordained Presbyterian minister, and I want you to know that Jesus is important to me, too. I hope that God’s love and peace come through my work on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”

Fred Rogers was an ordained minister, but he was no televangelist, and he never tried to impose his beliefs on anyone. Behind the cardigans, though, was a man of deep faith.

Using puppets rather than a pulpit, he preached a message of inherent worth and unconditional lovability to young viewers, encouraging them to express their emotions with honesty. The effects were darn near supernatural.

He was Protestant. But if Protestants had saints, Mister Rogers might already have been canonized.

When Rogers decided to pursue a career in television, it wasn’t fame he sought. While watching TV during seminary, he “saw people throwing pies at each other’s faces,” which he believed was both “demeaning behavior” and a missed opportunity.

In the wake of World War II, thousands of veterans returned from battle and started families. These shell-shocked heroes risked creating a generation of emotionally stunted children. Television was a perfect vehicle for teaching kids to cope with life’s difficulties and express their feelings, but it was used mostly for mindless entertainment.

“After graduating from seminary, the Presbyterian Church didn’t know what to do with Fred,” says Amy Hollingsworth, author of The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers. “So the presbytery gave him a special commission to be an evangelist to children through the media.”

Fred’s faith surfaced in subtle, indirect ways that most viewers might miss, but it infused all he did. He believed “the space between the television set and the viewer is holy ground,” but he trusted God to do the heavy lifting.

The wall of his office featured a framed picture of the Greek word for “grace,” a constant reminder of his belief that he could use television “for the broadcasting of grace through the land.” Before entering that office each day, Rogers would pray, “Dear God, let some word that is heard be yours.”

Rogers told kids they mattered, that they were worthy of love, and that emotions were to be embraced, not buried. He spoke to children like grown-ups, and helped them tackle topics such as anger, trust, honesty, courage and sadness.

“The world is not always a kind place,” Rogers once said. “That’s something all children learn for themselves, whether we want them to or not, but it’s something they really need our help to understand.”

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood helped young viewers process stress incurred during intense periods of cultural upheaval. When it would have been easy to demonize villains, Rogers instead forced viewers to tussle with a question Jesus himself was asked in the gospel of Luke: “Who is my neighbor?” While the question felt different depending on the circumstances, Rogers’ answer never wavered.

“His definition of ‘neighbor’ was whomever you happen to be with at the moment, especially if they are in need,” Hollingsworth said.

Rogers took an artisan’s approach to television production. Each show was designed to meet the psychological needs of children by giving them “a neighborhood expression of care,” in consultation with a team of experts. Rogers thought of himself as something of a surrogate parent, which is why he often utilized puppets and rarely featured other children—he didn’t want to create a sense of “sibling rivalry.”

His hard work helped his show hold its own against flashier, more expensive children’s programs in competing time slots. Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood pushed beyond surface-level entertainment and instilled children with a sense of joy, peace and kindness.

Researchers who compared viewers of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood with viewers of Sesame Street even found that Fred’s fans developed a greater level of patience.

In 1969, The Atlantic documented how the dialogue on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood often felt so personal that it would trigger a “byplay” from young viewers, in which they “may respond vocally to a question and Rogers, anticipating the reply, may follow through to his next point.”

But for some viewers, the connections went even deeper.

In 1998, Esquire reported the story of a young viewer of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood with an acute case of autism. The child had never spoken a word until one day he uttered, “X the Owl,” which was the name of one of Mister Rogers’ most popular puppets.

And the boy had never looked his father in the eye either, until the day his dad said, “Let’s go to the Neighborhood of Make-Believe.” After this, the boy began speaking and reading, which inspired the father to visit Fred Rogers personally to thank him for saving his son’s life.

Lauren Tewes, the actress who played the cruise director on the television show Love Boat, left the show in 1984 while struggling with a cocaine addiction. One particularly dark morning, the actress says she glanced at her television screen and saw the signature opening of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

Something inexplicable happened inside of her, which Tewes later attributed to “God speaking to me through the instrument of Mister Rogers.” She spent the next several decades sober.

Later in Rogers’ life, he recounted the story of a child who was being abused by his biological parents, who reportedly “wouldn’t even give him a winter blanket and wouldn’t give him a bed to sleep in.” Through encountering Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, the child began to hope that there were kind people in the world and became convinced that he too should be treated with respect.

The child called an abuse hotline and was rescued. If the story doesn’t seem exceptional enough, consider that the hotline operator who answered the phone adopted the boy.

These are anecdotal accounts, impossible to verify. But they’re of a piece with the stories often told about saints. In that, they reflect the remarkable connection that so many viewers formed with Rogers, and the extent to which many came to regard him not just as an entertainer, but as something very much more.

Rogers affected the lives of millions of children, and I count myself among them. On many afternoons, I sat in front of a television screen where Mister Rogers told me that I was lovable and I was enough. He said he was my friend, and I believed him. My life still bears the fingerprints of his influence.

I can still hear him signing off his show similar to the way he concluded his letter to Amy Melder: “You’ve made this day a special day by just your being you. There is no person in the whole world like you, and I like you just the way you are.” Some have suggested that this message sought to instill children with a sense of self-importance, but to believe that is to fundamentally misunderstand Fred Rogers. At the core of Rogers’ mission was the paradoxical Christian belief that the way to gain one’s life is to give it away.

“The underlying message of the Neighborhood,” Rogers once said, “is that if somebody cares about you, it’s possible that you’ll care about others. ‘You are special, and so is your neighbor’ — that part is essential: that you’re not the only special person in the world. The person you happen to be with at the moment is loved, too.”

He was right, of course, that everyone is special. But so was he. There was also no person in the world like Fred Rogers, and given the current state of American television, there might never be again. For nearly 40 years, he entered homes to bandage broken psyches, mend fences of division and preach peace.

Mister Rogers was not just special; he was a saint. He’ll never be officially offered that title, and he’d probably want it that way. Instead, he has been canonized in the hearts of his viewers — Saint Fred, the patron saint of neighborliness.

Jonathan Merritt is a contributing writer for The Atlantic and a senior columnist for Religion News Service. He has written more than 3,000 published articles in such publications as The New York Times, USA Today, Buzzfeed, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. He is the author of Jesus Is Better Than You Imagined and A Faith of Our Own: Following Jesus Beyond the Culture Wars. Copyright 2015, the Atlantic Media Company, as first published in The Atlantic. All rights reserved. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

PARTING WORDS

I would like to tell you what I often told you when you were much younger: I like you just the way you are. And what’s more, I’m so grateful to you for helping the children in your life to know that you’ll do everything you can to keep them safe and to help them express their feelings in ways that will bring healing in many different neighborhoods.”

— From the final episode of

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood

WINTER PARK WAS HIS NEIGHBORHOOD

Fred Rogers — or, as his fans knew him, Mister Rogers — was born in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. But Winter Park claims him as one of its own, in part because he graduated from Rollins College in 1951 with a degree in music composition.

It was at Rollins where he met his future wife, Joanne Byrd, and participated in an array of campus activities, serving on the chapel staff and as a member of the Community Service Club, the Student Music Guild, the French Club, the Welcoming Committee, the After Chapel Club and the Alpha Phi Lambda fraternity.

But he also formed enduring friendships in the city, and visited here regularly for the remainder of his life.

When in Winter Park, he nearly always dropped by the campus, swimming in the pool nearly every day — he was an intramural swimmer in his college days — and sometimes slipping into classes that interested him.

He counted John Sinclair, chairman of the Department of Music and artistic director of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, as one of his closest friends. Rogers’ nephew, renowned composer Daniel Crozier, continues the legacy as a professor of music theory at the college.

Suddenly, it seems — perhaps because of the turbulent times in which we live — Mister Rogers is more popular than ever. Certainly, his message of kindness and civility, which may have seemed corny to cynics 20 years ago, has never been more timely.

In 2018, marking the 50th anniversary of Rogers’ iconic children’s program, PBS broadcast a poignant documentary called Mister Rogers: It’s You I Like. Another documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in January, and will be released to theaters later this year. A U.S. postage stamp bearing his likeness was recently unveiled.

Oh, and there’s more. Tom Hanks has been signed to star in a big-budget Tristar biopic, You Are My Friend, inspired by a real-life friendship between Rogers and journalist Tom Junod.

In the film, Junod is shown as a hard-bitten reporter who reluctantly accepts an assignment to write a profile on Rogers for Esquire — and finds his worldview transformed in the process. The article, now considered a classic of magazine journalism, ran in 1998.

A release date for the film has not yet been announced. In the meantime, though, here are five things you may not have known about Fred Rogers:

- His testimony helped save the VCR and paved the way for Netflix.

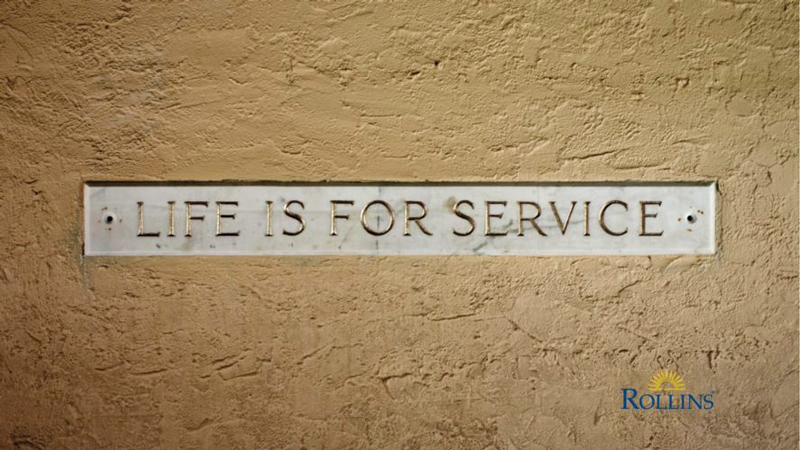

In 1976, Universal Studios filed a lawsuit against Sony Corporation to halt sale of the Betamax — the precursor to the VCR — claiming that home recording would damage television and film producers. When the case came before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1983, Rogers testified for Sony, saying he didn’t object to people taping his shows and watching them at a more convenient time — particularly if they were able to do so in a family setting. The court — which cited Rogers’ testimony — ruled in favor of Sony, and the case has served as a precedent for the popular recording and streaming technologies we enjoy today. - He was inspired by the “Life Is For Service” motto he saw at Rollins.

The talented music composition major — who transferred to Rollins from Dartmouth — took a photo of the inspirational engraving, which is on a wall near Strong Hall, and carried it in his wallet for years. It was finally framed and prominently placed on his desk. - He spoke at a kid-friendly speed of 124 words per minute.

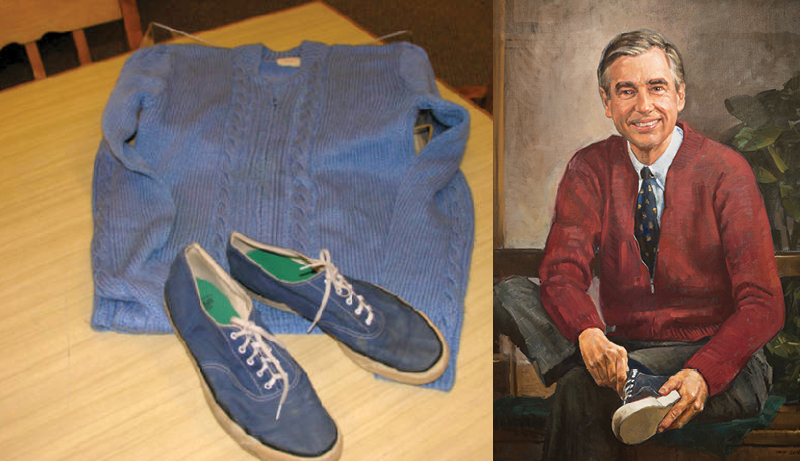

According to research, one reason why children were so captivated by Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood could be that Rogers’ speech was the perfect pace for children ages 3 to 5 to process. The average adult prefers to listen to speech at a pace of 150 to 160 words per minute. - His sweater and sneakers are housed in the Campus Library.

Rogers famously wore zip-front cardigans that were knitted by his mother. A blue cardigan and a pair of sneakers are among Rollins’ most treasured possessions, and may be seen in the college’s Department of Archives and Special Collections in Olin Library. Another cardigan — a red one — is kept at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. - He weighed exactly 143 pounds for the last 30 years of his life.

Rogers lived a healthy life and was disciplined in his daily routine. Journalist Tom Junod explained that Rogers found beauty in his weight of 143 pounds because “the number 143 means ‘I love you.’ It takes one letter to say ‘I’ and four letters to say ‘love’ and three letters to say ‘you.’ One hundred and forty-three.”

A version of this list originally appeared in Rollins 360, the campus magazine.