On February 3, 1926, a troupe of stagestruck Central Floridians—alongside student members of the Little Theater Workshop at Rollins College—presented four one-act plays before a packed house at The Beacham Theatre in downtown Orlando.

The inaugural production from the Orlando Little Theatre Players may not have been exceptionally polished, but it was, according to the Orlando Sentinel, “well balanced from beginning to end and without a dull moment.”

Under the direction of Orpha Pope Grey—head of the college’s dramatics and expression department and organizer of its on-campus Little Theater Workshop—students starred in Everybody’s Husband and The Camberley Triangle, while community members—friends and neighbors—starred in The Valiant and Thank You, Doctor.

Newspaper advertisements leading up to opening night had simply promised “four good one-act plays.” That low bar appears to have been comfortably cleared. Thank You, Doctor, for example, was described by the Sentinel as “so hilarious that the audience was laughing from start to finish.”

Although several of these plays were popular at the time, none—with the possible exception of The Valiant—is still performed a century later. But the Orlando Little Theatre Players (which was founded in 1925, hence its centennial celebration in the 2025-26 season) is still around and stronger than ever in its eighth—yes, eighth—iteration as Orlando Family Stage.

But the role of Winter Parkers in founding and nurturing a theater in adjacent Orlando is perhaps underappreciated. There was, of course, a Rollins connection from the very beginning; the college troupe presented some of its own shows under the new organization’s umbrella, while several other shows using only community casts were directed by Mrs. Grey.

The Oberlin (Ohio) College graduate would leave Winter Park three years later to supervise the department of dramatics, speech arts and expression at Seaborn Academy, a posh and private prep school on Davis Island in Tampa. Nonetheless, Mrs. Gray earns the distinction of being director of the first shows presented by the Orlando Little Theatre Players.

Two other Winter Park women, however, were integral, in their own ways, in the evolution of this seat-of-the-pants enterprise into a cultural asset that would, despite its roller-coaster history, persevere for a century and counting. If one were compelled to name the two godmothers of Orlando Family Stage, these women would surely be the primary candidates.

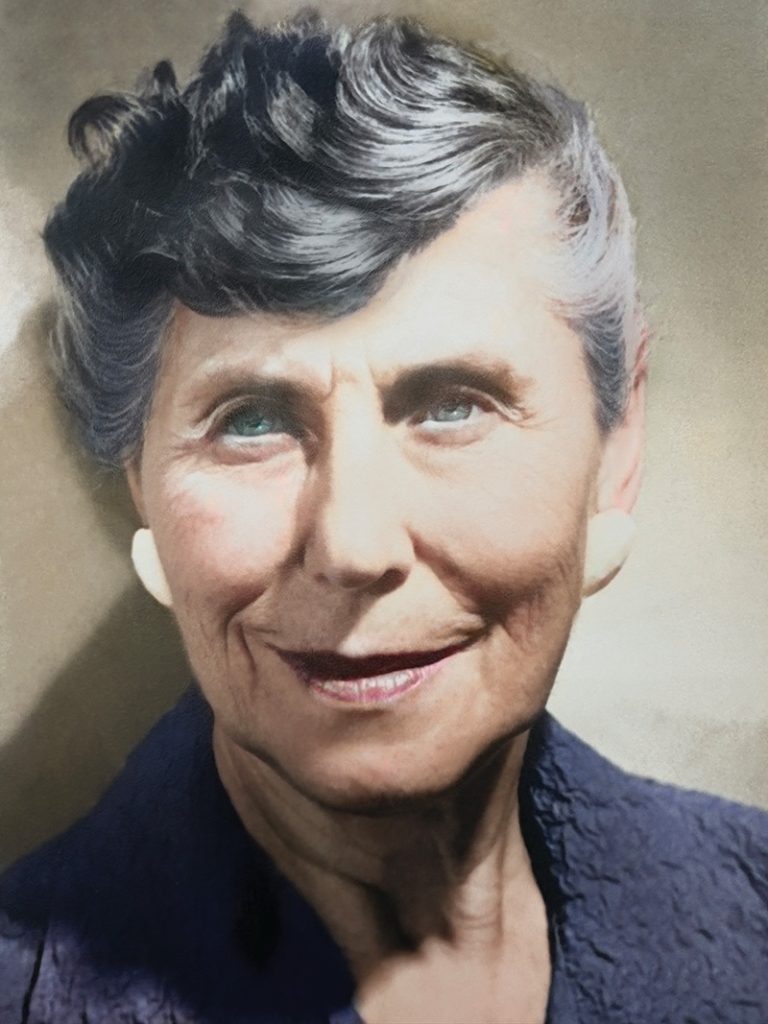

One was Evelyn Cole Duclos, a socially prominent and determined (but lovable) drama diva, while the other was Edyth Bassler Bush, a former dancer and actress whose legacy of good works is carried forward today by the Winter Park-based Edyth Bush Charitable Foundation. Both would undoubtedly be pleased at how far the theater has come, but baffled (or bemused) by the surreptitious route it took to get there.

ACT 1: NO LOFTY PRETENSIONS

No one active during the theater’s precarious early years could have imagined that this once-itinerant institution—which had no venue of its own until 1959—would become a nationally renowned mecca for youthful creativity and a leading-edge educational innovator affiliated with the largest university in Florida.

But, somehow, that’s exactly what happened. Since 2000, Orlando Family Stage has partnered with the University of Central Florida to host an innovative Master of Fine Arts program in Theater for Young Audiences (TYA)—making UCF’s the only such master’s program in the state (and perhaps the country) that offers training at its own off-campus professional community theater.

At the helm is Chris Brown, executive director, who has served for 15 years as production manager, general manager and interim executive director before “interim” was dropped from his title in 2019. The genial Brown, who successfully steered the operation through COVID-19 and oversaw a return to growth in the pandemic’s aftermath, was named one of the Orlando Business Journal’s 40 Under 40 in 2023.

“My comfort level is being backstage and pulling the rope that no one sees,” says Brown, who earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from UCF and an MFA in technical design and production from the Yale School of Drama (now the David Geffen School of Drama at Yale University). “I don’t want to be in the spotlight.”

Indeed, Brown correctly notes that, cumulatively, hundreds of people over the decades can claim a share for the success of Orlando Family Stage. Not least among them is his immediate predecessor, Gene Columbus, a retired Walt Disney World executive who, during his 11-year tenure, navigated the economic collapse of 2008 and 2009—and, at a crucial time, engineered a $200,000 grant from Bank of America.

Banner years during the past few decades is all the more impressive when you consider that, for most of the theater’s history, there was plenty of passion but no master plan—or, perhaps more accurately, there were many master plans that failed to reach fruition. A (not-so) brief review of the theater’s complicated and ill-documented saga reveals an institution that survived booms and busts, but at times—especially prior to its affiliation with UCF—struggled to find a niche.

The original effort, inspired by the “little theater” movement that swept the country following World War I, was a project not of the arts community but of the City of Orlando Board of Public Recreation and Playgrounds. The movement is often described as a challenge to commercial theater business models through the formation of small theaters that could be more artistically daring.

Orlando, however, had no such lofty pretensions. Donald A. Cheney, the first judge in Orlando’s juvenile court and an organizer of the theater, believed that such an organization could offer a wholesome diversion for young people who might otherwise get into mischief. Still others sought to elevate the city’s cultural quotient or to enjoy personal fulfillment through creative expression.

In early 1925, after the city sought to gauge interest through an announcement in the Sentinel, several hundred people attended an organizational meeting at the Sorosis Club, a women’s civic and social organization, where they heard a presentation and saw two one-act plays, Nevertheless and Mrs. Oakley’s Telephone, presented by the Rollins Little Theater Workshop.

And so it began. The assumption was that the fledgling Orlando Little Theatre Players would remain under the auspices of the city indefinitely and that a “theater specialist” would be hired to supervise the operation, start a children’s program and offer training for other civic organizations wishing to promote dramatics. The private sector, though, would have other ideas.

ACT 2: EAGER BUT ITINERANT

Following the success of the inaugural public performance—and with the blessing of the city—theater boosters formed a private membership organization and elected a slate of officers that included Henry S. Jacobs, who was a performer in The Valiant and a principal in the oddly-named Orlando Suburban Amusement Co., a real-estate concern that initially developed the neighborhood of College Park.

For years, plays were held mostly in school auditoriums, civic club halls and, for a time, a chapel at the old Orlando Army Air Force Base (later the Orlando Naval Training Center and now Baldwin Park). Early seasons usually encompassed eight to 10 performances—generally a triple- or quadruple-bill of proven one-act crowd pleasers—that were presented wherever a stage could be secured.

In 1934, the theater dropped the superfluous word “Players” and filed for incorporation as the slightly simplified Orlando Little Theatre. That year, Martin Flavin’s Broken Dishes, staged at Sorosis House, proved to be such a hit that it encored the following year at the Orlando Municipal Auditorium (later the Bob Carr Theater) and sold some 3,000 tickets.

What was all the fuss about? It seems that the romp about the travails of a henpecked husband, which premiered on Broadway in 1930 and featured a young Bette Davis, was apparently quite funny. It had been a big hit on stage and served as the foundation for several film adaptations, the first of which was Too Young to Marry in 1930.

But, well-received shows aside, the theater was inactive from 1942 to 1946 because of World War II and the resulting scarcity of male actors. When it reemerged in 1946, lying in wait was a splinter group of former participants calling itself the Community Players. The feuding groups negotiated a truce, merged operations, and the Orlando Little Theatre became the Orlando Players in 1953.

That same year, New York City residents Evelyn Cole Duclos and her husband, Aeneas—a painter, an occasional actor and a semiretired patent-maker with Western Electric—began to spend their winters in Winter Park. They were comfortable, not wealthy, and bought a relatively modest home near Aloma and Lakemont avenues.

Mrs. Duclos, a graduate of the University of Chicago with a degree in education, had been a prep school drama teacher and served as director of the Washington Square Church Players, an experimental Off-Broadway company based in Greenwich Village that was emblematic of the little theater movement’s avant-garde roots.

Naturally, then, the flamboyant native of Toronto was interested in opportunities to involve herself in local community theater. She quickly joined the Womans Club of Winter Park and was named drama chairman at a time when the club presented skits, readings and plays that involved members or guest artists.

In 1954, Mrs. Duclos directed a play for the club called The Orange Juice Quartet, about which no information could be found, and then a play or two every year, including several that she wrote, among them The Mouth of the Gift Horse in 1958. (The play would be restaged at the club in 1975—just a year prior to Mrs. Duclos’s death—and would star Orlando native and Miss Florida of 1974 Delta Burke.)

Mrs. Duclos also discovered the Orlando Players and landed a role in a 1954 staging of Tennessee William’s Summer and Smoke. “In those days, we were rehearsing in someone’s living room, a garage, or Ivey’s drug store,” she told the Sentinel in 1973. “I told them they’d never get anywhere until they found a permanent place for their plays.”

Still, the theater soldiered on and did the best it could with what it had. Among its greatest hits of the 1950s: The Bad Seed, presented in 1957 at the Syrian-Lebanese American Club and directed by Peter Dearing, a theater professor at Rollins. Dearing cast precocious Anne Hathaway, an 11-year-old junior high school student, who was said to have chewed up the scenery as pigtailed psychopath Rhoda Penmark.

In 1959, according to Sentinel columnist Jean Yothers, the theater’s name was changed yet again—to the Orlando Players Little Theatre—because “local yokels thought ‘Orlando Players’ was a ball club.” (In truth, the local yokels made a valid point.) By then, Mrs. Duclos—who, with her husband, had relocated permanently to Winter Park—was the theater’s president and had made finding it a proper home a priority.

ACT 3: BE IT EVER SO HUMBLE

It didn’t take long. The determined Mrs. Duclos located a modest bungalow at 813 Montana Avenue (now the Vajrapani Kadampa Buddhist Center), which under her leadership was converted into a modest 124-seat venue. “I knew it was only a steppingstone,” the get-it-done doyen told the Sentinel. “We wanted a theater in Loch Haven Park.”

Indeed, the city had already designated a site for a new theater in the 45-acre expanse. Board members, led by Mrs. Duclos, had even broken ground and installed a sign on the site that read “Help Us Grow.” As it happened, however, the all-too-literal “little theater” building would have to suffice for the next 14 years.

On October 14, 1959, John Van Druten’s Old Acquaintance—a frothy comedy that had enjoyed a Broadway run in 1940, and three years later had been adapted into a film starring Bette Davis (there she is again!)—became the first production staged at Montana Avenue and opened a six-show season.

Generally, the theater’s offerings in the coming years were well-reviewed—

especially by the Sentinel’s Sumner Rand, who also acted in several productions. At times, though, the box office was juiced by augmenting local talent with such dimming stars as Claire Luce, Julie Haydon and Harry Blackstone Jr.

In 1960, children’s summer programs began and, later, acting classes were offered for both children and adults. Children were taught by Howard Davis, who had appeared in numerous local productions and was a teacher at Union Park Junior High School. Adults were taught by Ginny Cortez and Sara Daspin, who would become icons in the local theater community as actors and directors.

Mrs. Duclos—who also acted in several of the theater’s productions, sometimes snaring scene-stealing roles as dotty eccentrics—continued to hold fundraising events and to bend the ear of Orlando Mayor Bob Carr about the viability of the Orlando Players Little Theatre. “Evelyn kept interest in the theater up at a time when it could have died down,” a friend told the Sentinel.

Indeed, Mrs. Duclos’s charm and determination won her friends and admirers but never enough money—at least not during her tenure—to move the theater from Montana Avenue to Loch Haven Park. The seeds that she had planted, though, would soon come to blossom. And, thankfully, she would live to see her vision become reality.

In 1964, Mrs. Duclos stepped down as president and became president emeritus. She remained deeply involved in the theater as a performer and a booster. And she accumulated a slew of accolades from other service clubs and civic groups in which she was involved, from the Daughters of the American Revolution to the Orlando Council of Beta Sigma Phi.

Perhaps the award that meant the most to her, though, was the theater’s Lillie Stoates Award as “Best Bit Player” for her role as “Nanny” in its staging of The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds. Still, as anyone who knew her can attest, Evelyn Cole Duclos, who died in 1976, was never a bit player in any endeavor she undertook.

(The Lillie Stoates Awards, first presented in 1998, are named for an Oxford, Mississippi-based rainmaker who came to Orlando in 1939 to rid local orange groves of a drought. The story goes that Stoates, who received tongue-in-cheek coverage in such publications as Time magazine, was successful and the citrus trees flourished as a result.)

Actress Virgina “Ginny” Light, who from the 1970s to her death in 2001 was a local theater stalwart who often played formidable ladies of a certain age, wrote warmly about her friend and colleague in a printed program for The Duclos Society, a luncheon series established in 1986.

(The invitation-only society was formed in 1969 under the auspices of the Civic Theatre Guild, an organization dedicated to supporting the theater’s mission. For a time the guild was the sponsoring entity for the theater’s children’s plays.) Light’s tribute, perhaps as colorful as the grande dame to whom it was dedicated, reads in part: “[Mrs. Duclos] was shameless in her pursuit of money for our theater. She sweet-talked, cajoled, bullied and enchanted dollars out of her friends and strangers.”

Added Light: “As sure as there’s a heaven, Evelyn has organized a theater group and, if they need a place to put on their plays up there, God had better watch out—he’s never had an angel like ours before.”

ACT 4: BOOM AND BUST

In 1968, the theater’s name was changed again, to the Central Florida Civic Theatre, and boosters renewed their push to raise money and move to Loch Haven Park. A $350,000 fundraising effort was initiated in 1969—but everyone involved realized that much more would be required. (The final cost came in at more than $450,000.)

Influential journalist Joseph L. Brechner—who had succeeded Mrs.

Duclos as president of the theater’s board and was a founder of WFTV-

Channel 9, the local ABC affiliate—kicked off the ambitious campaign with a thoughtful opinion piece in the Sentinel that encouraged financial support and asked: “What role will you play?”

Public backing for the effort, during which Brechner served as the “last lap” chairman, was strong, with hundreds of donations in smallish increments (usually far less than $1,000) with the exception of the Orlando-based Tupperware Corporation, which chipped in $60,000. By 1971, the grassroots effort had yielded $373,000.

Ground was broken for the state-of-the-art venue—designed by Nils Schweizer, a protégé of Frank Lloyd Wright—on April 18, 1972. But the following year brought a game-changing windfall that appeared to ensure the project’s completion as planned and its sustainability going forward.

The gift was thanks to Edyth Bassler Bush—an erstwhile actress and dancer who was the wife of 3M chairman Archibald “Archie” Granville Bush. The Bushes, like the Ducloses, were initially seasonal residents. They first visited in 1949, and the following year purchased the distinctive Asian-themed home that was originally occupied by bestselling author Irving Bacheller on the shores of Lake Maitland.

(In 1956, the couple demolished the home and replaced it with a modern showplace designed by the now-legendary James Gamble Rogers II. The home still stands in the exclusive Twelve Oaks neighborhood, a posh private peninsula off Park Avenue).

Archie, who started as an assistant bookkeeper for then-struggling 3M in 1909, was a sales manager for the company in 1919 when he met—and was smitten by—Edyth during a business trip to Chicago. The couple married that year, well before Archie amassed a fortune mainly through his early investments in 3M stock. (He even used Edyth’s $15,000 dowry to snare some additional shares.)

Edyth had given up her stage career—which appears to have been successful and included some international appearances—for life as a homemaker (albeit a homemaker who supervised a staff of 11.) But, like her savvy husband, she also became a philanthropist whose impact continues to reverberate through the Edyth Bush Charitable Foundation.

For several decades, most of her attention was lavished on her own Edyth Bush Little Theatre in St. Paul, Minnesota. Opened in 1940, the jewel box of a venue, which seated 275, had been a birthday gift to Edyth from Archie—so, as might be expected, no expense had been spared in its design and construction.

Recalled Mrs. Bush in a 1940 interview with the Minneapolis Star-Tribune: “It was after La Gamine [a play that she wrote and starred in at the Minneapolis Woman’s Club in the late 1930s] that Mr. Bush and I first talked about building a theater.” At least initially, she said, she demurred—after all, there was already a small theater on the ground floor of her home—but Archie was insistent.

Mrs. Bush continued: “I guess I looked at every old house, barn and garage for miles around, thinking I could find something that could be made into a little playhouse. Last year on my birthday, [Archie] said that he was going to give me my theater.” The project ultimately cost the “Scotch Tape King” more than $100,000—the equivalent of more than $2.3 million today.

The Edyth Bush Little Theatre began staging productions, some of them written by Mrs. Bush and some of them also starring the theater’s colorful namesake. During World War II, she dealt with the shortage of male actors by starting a children’s theater program, for which she wrote and directed the performances.

(The venue was donated to Hamline University in 1964, two years before Archie’s death and Edyth’s subsequent decision to live year-round in Winter Park. It was sold by the university to the Chimera Theater, another local performing arts company, in 1975, but now houses offices and is known as the Edyth Bush Building.)

The Central Florida Civic Theatre first reached out to Mrs. Bush via letter in 1967, when she was likely nearing 90 years of age. (1900 census records report her birth date as being 1879; but by 1910 the date had been changed to 1885 and then, by 1920, had again been nudged forward, to 1887.) In any case, according to a note written on a copy of the letter in the theater’s archives, her response was “positive.”

But what Mrs. Bush actually donated at the time—if anything—is not known. In 1970, following a series of strokes and other health issues, her fortune, estimated at $81 million, was placed under guardianship of the Commercial Bank of Winter Park, which had been founded by her husband. She died on November 20, 1972.

An existing Edyth Bush Foundation, which had been formed following Archie’s death, was reincorporated as the Edyth Bush Charitable Foundation in 1973 with a mission to “alleviate human suffering and to help people help themselves” as well to assist arts, education and human service organizations. (The foundation, headquartered in downtown Winter Park, has over the past five decades distributed more than $114 million.)

“Mrs. Bush believed that theater instilled skills that benefited children personally and, as adults, professionally,” says David Odahowski, the foundation’s president and CEO. “Following her passing, the foundation sought a meaningful way to honor her legacy.”

Meaningful? We’ll say! The amount was $332,375, a sum so generous that the building’s 330-seat proscenium-style auditorium was named the Edyth Bush Theatre. She never saw the venue—perhaps, as her health failed, she wasn’t even aware of it—but no one doubted that she would have been thrilled to take the stage for just one more earthly bow.

(The Tupperware Children’s Theatre, which opened in 1974, became a black-box space when the Ann Giles Densch Theatre for Young People was added on in 1990 to accommodate the program’s burgeoning growth. That 340-seat venue, now called the Universal Orlando Foundation Theater, was revamped and relaunched in 2000.)

The Edyth Bush Charitable Foundation was, and remains, the theater’s most important and consistent benefactor. From 1972 through 2025, it has given the operation more than $1.8 million—including most recently $500,000 to support various activities related to its centennial, among them the first Florida Children’s Book Festival in February. (See page 32).

But the question lingers: Who has been in charge of the Pearly Gates Little Theatre, Mrs. Duclos or Mrs. Bush?

If their lives are any indicator, then presumably Mrs. Duclos is the general manager, rustling up afterlife audiences for a promised-land production of La Gamine, which, as always, will star Edyth Bassler Bush in her signature role as Carolotta le Couvrier. But if that play also offers a showy bit part for an elderly eccentric, you can bet that no one will overlook Evelyn Cole Duclos.

ACT 5: BUTTERFLIES AREN’T FREE

On October 18, 1973, the first event at the brand-new Central Florida Civic Theatre was a gala preview for donors of Butterflies Are Free, which featured Julia Meade—a stage and screen actress perhaps best known for her live commercials on TV—as Mrs. Baker, the overprotective mother of a young blind man who, against her wishes, moves into his own apartment and begins a romance with his freethinking neighbor.

That inaugural performance was notable, in part, because actress Gloria Swanson (Sunset Boulevard) quietly entered and just as quietly exited—although no one knew of her presence except a few tight-lipped theater insiders. Miss Swanson, who had played Mrs. Baker on Broadway, didn’t want her attendance to distract from the performance of her friend Meade.

The rest of the season included Anything Goes, The Lion in Winter, Our Town, Arsenic and Old Lace and The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds. All were sellouts well in advance; the theater had notched some 1,500 season ticket holders fully four months before opening its doors. (There had been 410 season ticket holders at Montana Avenue.)

More good things began happening. The first season of children’s plays was launched in 1975, while a second-stage series that offered more provocative fare was introduced in 1978, both in the Tupperware Children’s Theatre. A drama academy was created with separate programs for young people (grades one through 12) and adults.

Stalwart local actors became audience favorites in the mainstage productions, among them Gail Bartell, Alan Brune, Trudy Brunner, Jesse Charles, David Clevinger, Ginny Cortez, Violet Curry, the DeWoodys (Steve and Sandy), Mark Ferrera, Betty Fenner, Susie Findell, Connie Foster, Mary Fraizer, Patrice Gilbert, Denise Gilman, Ray Hatch, Tommy Keesling and Ginny Light (and her daughter, Davin).

Also John McComb, the Mitchells (Ray and Liz), the Mansfields (Ted and Geri), Terry Newby, Pam O’Bannon, Peg O’Keefe, Bob Niemyer, Jason Opsahl, Fred Pappia, Janine Papin, Katrina Ploof, Sumner Rand, Peter Rocchio. Jim Sayers, Mark Edward Smith, Bryant Simms, Patrice Shirer, Paul Vogt and Bryce Ward among many others who are fondly remembered by theater patrons.

Soon-to-be-celebrity alumni include Wayne Brady, a Dr. Phillips High School graduate and an improv specialist who became a star of TV and Broadway; and Delta Burke, a Colonial High School graduate and former Miss Florida who won fame as Suzanne Sugarbaker on ABC’s Designing Women.

Also Davis Gaines, an Edgewater High School graduate who played the title role 2,000 times in Phantom of the Opera; Mandy Moore, a Park Maitland School and a Bishop Moore High School graduate who achieved pop music stardom; and Tom Nowicki, a Winter Park High School graduate who has appeared in more than 160 films and TV shows (most recently Bad Monkey on Apple TV+).

In 1997, when an agreement was inked with the Actors’ Equity Association that allowed the theater to hire union-represented actors—albeit at decidedly non-union rates—the theater advertised its “first full equity season” for mainstage shows, which included Tom Kushner’s provocative Millennium Approaches, the first half of his Pulitzer-winning Angels in America.

ACT 6: A DEGREE OF DIFFERENCE

At the same time, however, newer (and perhaps more edgy) live-entertainment options had already begun to erode the theater’s audiences and divide its donors. Dwindling attendance, combined with crushing debt and staff resignations led to what might have been the theater’s demise.

In fact, the entire complex was closed in the summer of 2000 because of its poor physical condition. The venues would remain dark for three years.

“Nobody has been sure what kind of theater the company has been trying to be,” wrote Sentinel arts critic Elizabeth Maupin during the turmoil. “And the kind it used to be, a small-town theater with amateur actors, no longer works in a community as expansive and diverse as Orlando.”

Clearly, a reinvention that went beyond a facility upgrade and another name change was required. So Orlando Mayor Glenda Hood and UCF President John Hitt formed a community coalition that engineered a just-in-the-nick-of-time merger with the theater department of UCF’s College of Arts and Sciences, which needed a home for a proposed theater-related MFA program.

(To elaborate: Central Florida Civic Theatre Inc. assigned its land lease with the city—which still owned the run-down buildings—to UCF, which in turn made $2 million in repairs and renovations. During the transition the prior nonprofit under which the theater operated was disbanded, the board was asked to resign and private donors were sought to satisfy a debt load of $340,000 that UCF did not wish to assume.)

Although some local theater aficionados feared that their still-beloved community playhouse would become an academic unit of the university and lose its hometown focus, their concerns proved unfounded. A generic placeholder name was chosen: the UCF Civic Theatre, which debuted as the Orlando Repertory Theatre—with a season of all children’s shows—in 2003. (It remains the state’s only professional theater dedicated to young audiences.)

The Rep, as the operation was then colloquially known, became fully integrated with UCF’s MFA program, which had expanded its focus to embrace TYA. Many students—who collaborated with professional artists, technicians and administrators—graduated from the program and were quickly hired as executives of other nonprofit youth-oriented theaters around the country.

“I get calls all the time from professional theaters looking to hire our graduates,” says Jeff Revels, who joined the organization in 1995 as a box office assistant, then became education director and was appointed artistic director in 2006. “We have people [working] at places like Lincoln Center and the Kennedy Center.”

So thoroughly joined at the hip are the theater and the university’s theater program that some Orlando Family Stage employees are also adjunct faculty members at UCF, including Brown, the executive director; Tara Kromer, the props manager; and Emily Freeman, the senior director of development.

In 2023, following in-depth market research, the Rep changed its name to Orlando Family Stage to better reflect its exclusive focus. The new handle didn’t indicate a change of direction—the theater was never, by definition, a repertory theater—as much as it affirmed the existing mission: “Empowering young people to be brave and empathetic through quality theatrical productions.”

In addition to its seasonal productions, that lofty goal is reinforced by such successful ongoing programs as the Youth Academy, which offers classes and workshops, and Theater for the Very Young, which offers immersive experiences for early learners such as “Baby & Me” and “Toddler Story Strolls.”

Also in 2023, the theater purchased MicheLee Puppets, a beloved puppetry organization with a rich 38-year history, to ensure the artistic legacy of its founder, the late Tracey Conner. The puppet troupe, which makes presentations about such topics as nutrition, exercise, science, making friends and dealing with bullies, fits the theater’s mission and speaks to its demographic.

During its 100th anniversary season, Orlando Family Stage—which has a $4 million annual operating budget—plans to focus on enhancing the guest experience with building upgrades, both cosmetic and functional, funded by a $4 million grant from Orange County’s Tourist Development Tax.

It will likewise bolster fundraising through its “100 Seats for 100 Years” program, in which donors—corporate and individual—will be solicited to invest $2,500 each to provide theater experiences for 100 children. That would be a 60 percent increase over last year’s effort.

A major anniversary-season success has been A Charlie Brown Christmas, which set attendance records locally and necessitated adding shows. The theater, in partnership with New York-based Gershwin Entertainment Corporation, also sent a touring company of the Peanuts gang to such cities as Cincinnati; Brooklyn; Washington, D.C.; Denver; Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

“Reaching 100 years is more than a milestone—it’s a testament to the power of storytelling, education and the arts to unite and inspire,” says the Edyth Bush Charitable Foundation’s Odahowski. “Orlando Family Stage has nurtured creativity, sparked imagination, and built community for a century.”

He adds: “We’re honored to support its celebration and ensure its legacy continues to thrive. It has not only stood the test of time—it has helped shape the cultural identity of our region.”

ORLANDO FAMILY STAGE

Address: 1001 East Princeton Street (Loch Haven Park), Orlando, FL 32803

Phone: 407-896-7365

Website: orlandofamilystage.com

Venues: Edyth Bush Theatre (capacity 330); Universal Orlando Foundation Theatre (capacity 340); Black Box Theatre (capacity 100)

Upcoming Shows: Tiara’s Hat Parade (February 9 to 22, Universal Family Theatre); Lilly and the Pirates (February 20 to March 20, Edyth Bush Edyth Bush Theatre); Disney and Pixar’s Finding Nemo (April 2 to May 8, Universal Family Theatre).

Upcoming Events: Orlando Children’s Book Festival (February 20 to 26, various locations); Prom: Step Into the Story (March 27, annual fundraising gala, Winter Park Library)

OFS SALUTES WONDER-YEARS WORDSMITHS

The Florida Book Festival will debut as one of the few kid-lit events in the U.S.

The Florida Children’s Book Festival will make its entrance at Orlando’s Loch Haven Park as the first of its kind in the state and one of only a few such child-centered book festivals in the country. It’s being presented through a partnership of 100-year-old Orlando Family Stage and 11-year-old Writer’s Block Bookstore in Winter Park.

It seems to be a match that was simply meant to be. The theater and the bookstore have a “shared belief in the power of stories to bring families together,” says Lauren Zimmerman, owner of Writer’s Block, a plucky independent operation with retail locations in Winter Park and Winter Garden and an outpost slated to open sometime next year in the remodeled concession area at Orlando International Airport.

The book festival is slated for Friday, Saturday and Sunday, February 20, 21 and 22, with author talks, book signings, live readings, stage performances and more. The exact schedule of events had not been finalized at press time.

Some two dozen children’s-book authors are expected to attend, half of them from Florida. Friday has been designated Teacher Appreciation Day and will include sessions addressing literacy and classroom engagement.

Over the long history of Orlando Family Stage—including eight iterations and name changes since 1925—almost 90 percent of its plays have been drawn from children’s literature, says Chris Brown, the theater’s executive director.

And, thanks to its Target Family Theatre Festival—which began in 2007 and was produced annually over the course of several summers—the theater has experience producing major crowd-pleasing events. Brown says that a casual conversation sparked the collaboration with Writer’s Block.

“Lauren and I were talking one day and she said, ‘I hate that we don’t have a children’s book festival in Florida,’” recalls Brown. “We realized that we have this beautiful park and decided to do the festival, have it spill out into the park and to include our other arts partners over time.”

The three-day event will be an intentional celebration of books and reading at a time when there’s contention over what books are appropriate for children and when reading tests scores haven’t recovered since the pandemic.

Zimmerman says that she is grateful for the theater’s willingness to envision the festival on a meaningful scale. She notes: “Orlando Family Stage embraced this concept in every aspect—creative, logistical, planning, digital presence and making the event a priority.”

Highlights of the event will include two productions from the theater’s centennial season. Book characters will jump from the pages in Tiara’s Hat Parade, a play adapted from a 2020 picture book by Kelly Starling Lyons, and Lilly and the Pirates, a musical adapted from a 2010 middle-grade book by Phyllis Root.

Tiara’s Hat Parade, commissioned by Orlando Family Stage in partnership with four out-of-state children’s theaters, tells the story of an African American mother and daughter and their family’s hat shop. In Lilly and the Pirates, an adventuresome 10-year-old heroine sets off over the sea to save her shipwrecked parents and meets up with a wacky band of pirates.

Admission to these productions will be free during the festival—but both have longer regular runs in February and March with tickets available for purchase. Lyons will be at the festival although Root’s attendance hadn’t yet been confirmed at press time.

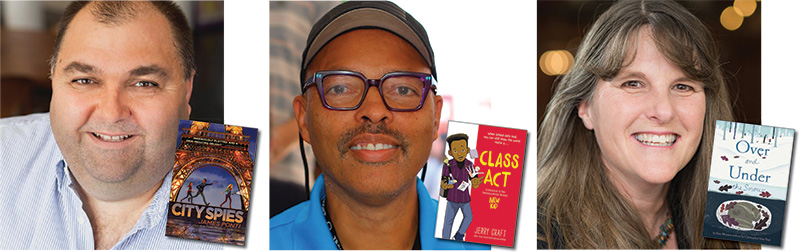

Among the Florida authors who will appear are James Ponti, an Orlando resident whose bestselling middle-grade book series include City Spies and The Sherlock Society, and Jerry Craft, the Newbery Medal and Coretta Scott King Award-winning author/illustrator of the graphic novels New Kid and Class Act.

“A thriving and sustaining children’s book festival is an incredible gift for a community,” says Ponti, who has participated in such festivals around the country.“It takes hard work and time, and I’m so excited that Central Florida is taking this step. I can’t wait to be a part of it.”

Also attending will be Kate Messner, an award-winning author of the picture-book nature series that began with Over and Under the Snow and the middle-grade book The Brilliant Fall of Gianna Z., which snared the E.B. White Read Aloud Medal. Messner, who lives in Vermont along Lake Champlain, was a TV reporter and English teacher before becoming a kid-lit luminary.

Other participating authors will be equally familiar to youngsters (and their parents), including Nicole D. Collier, Meghan McCarthy, Audrey Perrott, Rekha S. Rajan, Amar Shah, Taryn Souders and Salina Yoon.

“Children, very aware of these authors, come into the bookstore asking for their series,” says Liz Fleming, general manager and buyer for Writer’s Block. “To the kids, they’re celebrities. While the festival is for everyone and meant to be family-focused, the heart of it is giving kids the chance to meet and connect with the people who make the stories they love.”

Sometimes, says Brown, the theater tells stories and sometimes it educates. But it always seeks the fuller development of its young audience members. Live performance, he adds, is just a tool through which this overarching goal is accomplished.

“I think what is going to come out at the end of February is going to be really special and something we continue to do for a long time,” notes Brown. “I think it helps us be more important in the world. We’re not just here to do shows and plays. We are here to make kids love books and reading.”

For more information, call 407-896-7365 or visit orlandofamilystage.com.

—Catherine Hinman