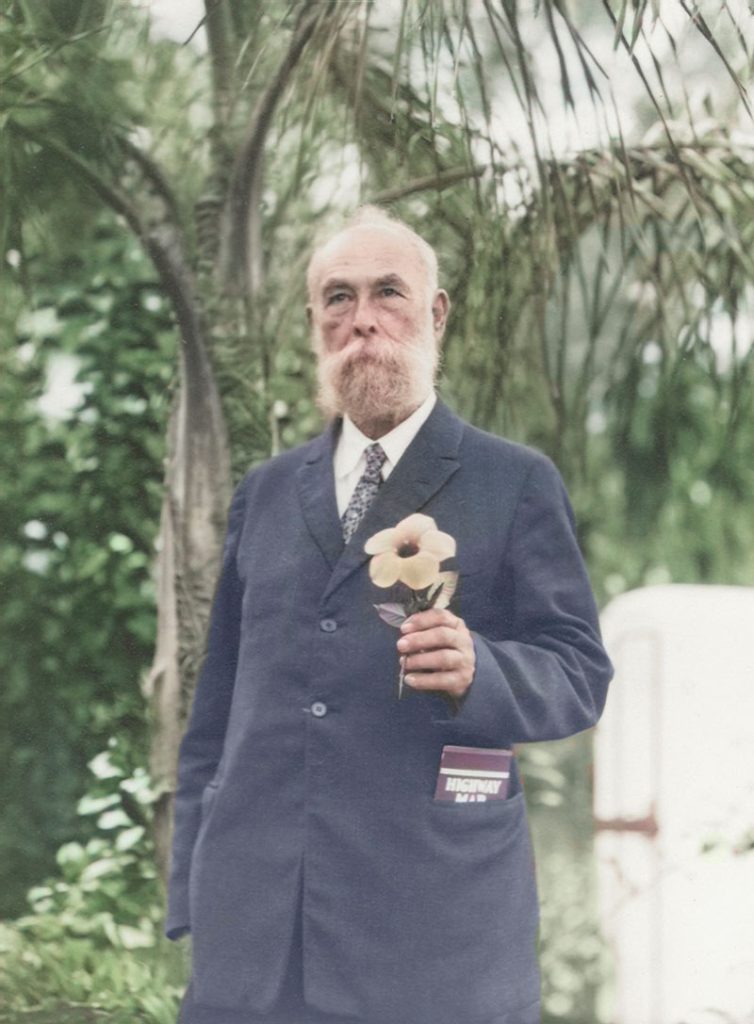

Leonardo da Vinci once said: “The orchid, with its many forms, is a reminder that life is full of surprises.” If that’s so (and would anyone argue that it’s not?) then even Theodore L. Mead must have been surprised, at least sometimes, by the lush and sensual flowers that he hybridized at his Oviedo estate, dubbed “Wait-A-Bit.”

Mead, of course, is the botanist for whom Mead Botanical Garden in Winter Park is named. Much of this issue is dedicated to the past (and the future) of the remarkable 58-acre expanse, which Mead himself, who died in 1936, never saw.

The garden was opened to the public 85 years ago, thanks in large part to the herculean efforts of Edwin Osgood Grover, the professor of books at Rollins College, and John “Jack” Connery, the erstwhile Eagle Scout, who joined forces to create this verdant open-to-the-public tribute to a man whom they both admired.

For all Mead’s accomplishments, however, one that he missed was being the cover artist for Winter Park Magazine (which, it must be noted, didn’t exist at the time). Still, the oversight has been remedied with this issue, which features a stunning hybridized orchid that Mead photographed around 1904.

First and foremost a scientist, Mead never intended for this or other such images to be stunning artistic creations in and of themselves. He photographed the results of his experiments for documentation, using 5-by-7-inch glass negatives that he developed in a small darkroom at Wait-a-Bit. He then printed and hand-colored the images.

An album of these dreamlike works of art (excuse us, we mean works of documentation) can be found in the Rollins Department of Archives & Special Collections. The always-accommodating Wenxian Zhang, director of the archives, allowed us to peruse the college’s Mead-related files and to select several images from the album to be scanned.

We, in turn, provided the scans to Will Setzer, owner of Circle 7 Design Studio, who carefully eliminated the tatters, stains and blemishes that you’ll inevitably find on photographs that are more than 120 years old. He then adjusted the color to compensate for fading. The results, we think you’ll agree, are spectacular.

What, then, is the species of orchid shown on the cover? Well, to be honest, we have no idea. Usually, Mead scrawled the names that he gave his hybridized orchids (“my children,” as he referred to them) directly on the images. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, he didn’t label this one.

We consulted Paul Butler, author of the definitive Mead biography (see page 24), but even he didn’t recognize this particular flower. That’s quite understandable, since there are at least 25,000 species of orchids (10,000 of which are found in tropical climates). Many of those developed by Mead, a prolific hybridizer, never went into wide circulation.

All we can say for sure is that it’s a real beauty. And we can leave you with this fun fact: The word “orchid” comes from the Greek word “orchis,” meaning testicle, because of the shape of the root tubers in some species. But before anyone tries to censor this issue, please remember that we’ve shown only the petals, not the naughty parts.