Additional Material by Leslie Poole

Additional Research by Paul Butler

A small white egret, eyeing glassy pond water in search of silvery minnows, balances on a rock. Two gopher tortoises wrestle head-to-head in a slow-motion battle of wills. A bicyclist takes a break, peering up into an enormous pine tree from which wafts a windborne tune.

These are the creatures of Winter Park’s Mead Botanical Garden—humans, birds, reptiles and fish—that have found relief and sustenance in its 48 acres of precious green space tucked among a municipal tennis complex, railroad tracks, apartment buildings and comfortable homes.

But beyond its shady bricked main entry, unobtrusively situated at the intersection of Garden Drive and Denning Drive, this urban oasis offers calm amid chaos and an opportunity to experience a different kind of park—one that combines planted gardens with restored natural areas.

It’s a quiet, verdant haven from harassment that allows the human spirit to rise while supporting natural habitats that have disappeared from much of Central Florida.

The garden welcomes about 70,000 people per year who picnic, birdwatch, meditate, practice yoga or thoughtfully wander around and soak up the sights, sounds and scents. While in the garden, it’s easy to forget that you’re just a jaunt from busy U.S. 17-92 and a bustling business district that includes Park Avenue.

“Winter Park’s Natural Place,” which celebrates its 85th anniversary this year, is owned by the City of Winter Park and, since 2012, has been operated by Mead Botanical Garden Inc. (MBG), an independent nonprofit. MBG and its stalwart volunteers are credited with revitalizing this under-the-radar refuge after the so-called “dark years” of management—some would say mismanagement—by the City of Winter Park.

“We stuck with it and that’s what it takes,” says Beverly Lassiter, a former Winter Park Garden Club president and the founding chair of MBG. “We cared, and we hoped that would make other people care. We were planning, dreaming and hoping that the garden would one day reach its full potential. Maybe now it’s finally the garden’s time.”

During the anniversary, boosters are revisiting the roller-coaster history of the garden. “It’s a miracle that it’s still here,” adds Lassiter. But they’re also looking ahead, and, in their ongoing partnership with the city, are implementing major enhancements.

Specifics are being codified in an ambitious new five-year strategic plan nearing completion with the support of the Washington, D.C.-based DeVos Institute for Arts and Nonprofit Management. (The DeVos family owns the NBA’s Orlando Magic.)

Of course, you could fill a bookshelf with the plethora of five-year plans that have been announced with great fanfare and subsequently ignored. But there’s every reason to believe that this time the outcome will be different, in part because you can already see the changes taking place.

“The plan is all about elevating the visitor experience,” says MBG Executive Director Cynthia Hasenau, who will retire this summer after 12 years at the helm. She supervises a full-time staff of just three: Emily Smith, programs and volunteer initiatives manager; Valerie Fetterolf, community engagement manager; and Olivia Brown, programs and social media coordinator. Phyllis Miller, the bookkeeper, is part-time.

The garden’s annual operating budget is about $400,000—less than $100,000 of which comes from the city. That’s little more than a rounding error in an overall city budget that now tops $214 million. MBG generates its earned income from donations, activities, rentals and memberships, while trowel-ready volunteers provide about 8,000 hours of service annually.

“An ideal budget would be about twice the amount that it is now,” says Tom McMacken, chair of the nonprofit’s board of trustees and a former city commissioner. “But I think it’s on our nickel to explain what we’re all about and to earn that kind of support.”

Arguably the centerpiece of the proposed enhancements will be the creation of a two-acre “Garden Within a Garden” that will enliven a now-unremarkable field northwest of the entrance. That’s where the current greenhouse sits catty-cornered from a charming but modest al fresco wedding venue.

The grassy expanse, known as the Legacy Garden, has admittedly not been the scene of much actual gardening apart from the carefully tended planted areas that surround the greenhouse. That’s because, until recently, the space has been used for event parking. Handy, perhaps, but hardly ideal for horticultural endeavors.

However, plans call for the promising parcel to be blanketed by a collection of themed display gardens that will contain tropical, native, edible and flowering plants and will connect the existing Camellia Garden and Yew Grove. A state-of-the-art greenhouse will replace the existing structure and become home to its collection of orchids, bromeliads, begonias and cycads.

“People love the natural landscape found throughout most of our property,” says Hasenau. “But this project will offer a much more cultivated, curated experience within a compact area. It will be inspirational and educational.”

Helping to design the Legacy Garden enhancement is Tres Fromme with Sanford-based 3. Fromme Design. Fromme’s extensive portfolio includes Georgia’s Atlanta Botanical Garden; Cheekwood Estate & Gardens in Nashville, Tennessee; the Huntsville Botanical Garden in Huntsville, Alabama; and the Tucson Botanical Gardens in Tucson, Arizona.

“We’re going to create spaces that people will recognize as gardens and not natural habitats,” says Fromme. There’ll be individual “rooms” of edibles and native plants as well as more exotic offerings. The wedding area, called the Celebration Garden, will be better defined by borders of flowers and foliage.

Also under construction is a new pathway that will originate at the Legacy Garden, then meander through the Camellia Garden and around the north side of the stormwater marsh before it completes a quarter-mile loop back to its starting point. It’s being built with accessibility in mind.

Existing trails, scenic though they may be, are mostly dirt (sometimes mulch) with tripping hazards from jutting tree roots and cypress knobs. This one will be surfaced with crushed granite that’s traversable even for those using wheelchairs or other mobility aids. Design consultants included the Winter Park-based Center for Independent Living.

The city, in the meantime, is using a $2.2 million grant from the federal Natural Resources Conservation Services (NRCS) program to conduct the Howell Creek Stabilization Project, which will stem erosion, stabilize creek banks, remove sediment and restore native vegetation following damage from Hurricane Ian.

Howell Creek—which delineates the garden’s eastern border—brings water from the wetlands near Orlando’s Spring Lake through Winter Park and into a lake system that eventually connects to the St. Johns River. The portion of the creek that runs through the garden is its longest uninterrupted stretch and provides an important habitat and travel avenue for wading birds, otters, turtles and fish.

“Our goal is to both restore the creek and armor it against future hurricanes,” says Gloria Eby, director of the city’s Natural Resources & Sustainability Division. In addition, a long-closed boardwalk through the garden’s wetlands will be restored by the city through a $500,000 grant from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection Recreational Trails Program.

The city put up matching funds of $125,000, which will enable work to begin this summer, according to Eby, who says that about 2,100 linear feet of boardwalk will be added. That means garden visitors will be able to explore dense and otherwise all-but-impenetrable sloughs adjacent to the wetlands around Lake Lillian.

In addition, a new pollinator garden has been installed on the north side of Alice’s Pond by Orange and Seminole County Master Gardeners, affiliates of the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Interpretive and directional signage has also been installed throughout the garden.

The greenhouse, too, has been upgraded and the Discovery Barn—home to an array of activities for children, including an annual Young Naturalist Summer Camp that attracted some 525 registrants last year—has been remodeled.

These newer initiatives complement projects completed during the pandemic years—when daily visitations soared—including the renovation and expansion of the “eco-chic” Azalea Lodge event space, construction of a new gravel parking lot and expansion of the stage at the frilly Little Amphitheater.

Other improvements were made as public health officials encouraged outdoor activities. For example, there was the construction of a substantial new picnic pavilion, replacement of a dilapidated creekside footbridge and installation of a garden by the Tarflower Chapter of the Florida Native Plant Society.

Some projects have been funded by the city, while others have been paid from the coffers of MBG. “We don’t work in isolation,” says Hasenau. “We plan and coordinate with our city partners.” For example, the city and the garden recently split the cost of replacing the wind-battered canvas “sails” that flank the stage at The Grove.

A major capital campaign will soon get underway to raise funds for new projects envisioned in the master plan. McMacken figures that the organization will need to raise about $3 million over five years to complete everything on the wish list.

“Just the greenhouse will be more than $1 million,” he says. “We’re going to do it in phases and stages as we’re able.” Not surprisingly, he adds, a major responsibility for the yet-to-be-chosen new executive director will be development.

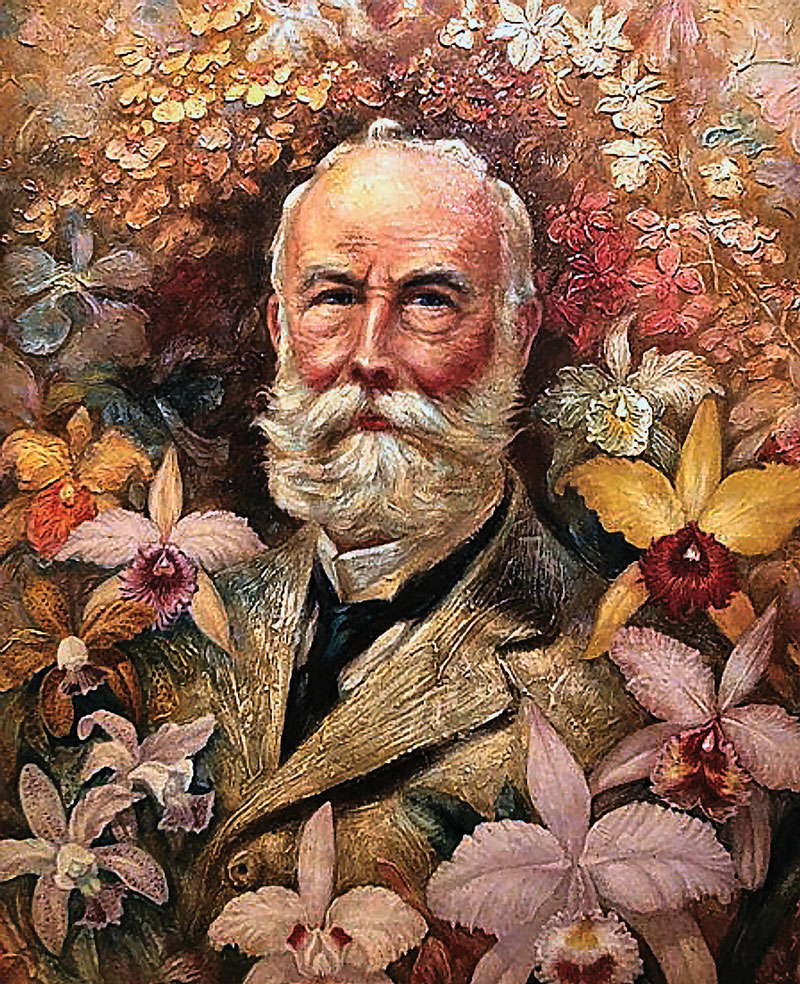

But you may fairly wonder why a swath of Old Florida wilderness even exists in a city that has been built out for decades and where property values are stratospheric. And who was Theodore L. Mead, the man for whom the garden was named?

The history of the garden—and the backstories of the people who launched such an audacious project—is in many ways as fascinating as the garden itself. But that history is, in stretches, as murky as the property’s heavily forested (and currently impenetrable) sloughs.

JACK AND UNCLE TEDDY

If you only know the Mead name through the garden—or perhaps through a ’70s-era subdivision in Oviedo called Mead Manor, where his groves once stood—then you’ll enjoy meeting the precocious youngster, the rugged adventurer, the pioneering citrus grower, the brilliant scientist and the beloved scoutmaster.

Theodore Luqueer Mead was born in 1852 to Samuel and Mary Mead in Fishkill, New York, 60 miles up the Hudson River from New York City. Mary was deeply religious, while Samuel, the well-to-do son of a wholesale grocer, might best be described as a freethinker. But the two made a congenial couple and were equally indulgent of young “Theo’s” interests in plants and insects.

In 1867, he and his mother enjoyed a seven-month tour of Europe, where the youngster became fascinated by exhibits of machinery at the French International Expedition. In Florence, he wrote, he was “rather intrigued by Galileo’s dried finger … and also by the stuffed skin of a saint.” Indeed, what 15-year-old wouldn’t be?

Fatefully, while in Europe he also wheedled his mother into buying him a large and comprehensive collection of butterflies—it cost $50, the equivalent of more than $800 today—and sparked a lifelong passion for studying and collecting the winged creatures. The family first visited Florida in 1868, where young Mead was thrilled to find and net a rare Papilio calverleyi around the town of Enterprise in what is now Volusia County.

The 16-year-old, wishing to learn from the best, wrote to William H. Edwards, author of Butterflies of North America, and was invited to spend the summer of 1869 as an apprentice at his home in Coalburg, West Virginia. Edwards, the country’s foremost expert in lepidoptera (the study of butterflies and moths), noted of Mead: “I can see with his eyes and hunt with his net quite as well as if I was out myself.”

In subsequent years, Edwards released two more volumes of Butterflies of North America, these with contributions from his now-frequent collaborator, Mead. Lavishly illustrated with hand-colored lithographic plates, the books are considered seminal works of natural history and cemented the reputation of Edwards—who had become to butterflies what Audubon, decades before, had become to birds.

After several months chasing specimens on the 30,000 acres owned by Edwards, the peripatetic Mead returned to New York and joined his brother, Sammy, at the Columbia School of Mines. Two years later, the Mead brothers accompanied the Edwards family on a government-sponsored mapping expedition of the Colorado Rockies.

There, Mead gathered 3,800 butterfly specimens—including 28 new species—several of which were named by Edwards for Mead. He also explored by horseback an area now called the Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument. There he found an array of fossilized insects—including a variety of termites that had previously been unknown.

In 1874, Mead enrolled at Cornell University, where he won $20 for the best lecture on a subject in physiology based on his butterfly research. But in 1875, he was devastated when Sammy, with whom he was extremely close, accidentally shot and killed himself while preparing for a hunting trip.

Still, Mead managed to graduate in 1877 with a degree in civil engineering. He and his parents then embarked on a six-month-long nature excursion to California, traveling by steamer from New York to Panama and up the coast to San Francisco, then returning via Salt Lake City and Chicago. Along the way he collected cacti and more butterflies.

In 1881, the Meads returned permanently to Florida, moving to the town of Eustis in what is now Lake County. Mead’s father bought his surviving son 90 acres for citrus growing and an additional 800 acres of pine forest as an investment.

The following year, Mead married Edith Edwards, daughter of his entomological mentor, after receiving assurance that she would not indulge in evangelism. Mead, much to his fundamentalist mother’s vocal dismay, was an adherent of Darwinism, as was Edwards.

Wrote Edith: “You won’t have to fear having chosen a ‘female revivalist.’ As you know, I don’t approve of that sort of thing. I believe in complete freedom of conscience, and shall never try to make you, dear boy, try to believe as I do where you can’t.”

After honeymooning in England, the couple returned to Eustis and became frontier citrus growers. Although Mead also began experiments with ornamental and subtropical plants, the operation was a financial drain that prompted the sale of his cherished butterfly collection to raise cash.

Several years later Mead soured on Eustis, which he described with unusual vitriol as “Philistine to the last degree, so much so that even I, who am most tolerant of almost every form of crudity, get tired and disgusted with it.” The couple moved in 1886 to Oviedo, an agricultural town south of Lake Jessup in what is now eastern Seminole County.

With financial assistance from Mead’s parents, the couple bought an 85-acre grove around Lake Charm and built a home that they whimsically dubbed “Wait-A-Bit.” Across the small lake, Henry Foster, a business-savvy homeopathic physician and part-time citrus grower, maintained a winter home. Foster’s wife, Mary, was Edith’s aunt.

The Fosters—tireless boosters of the area who had encouraged the Meads to relocate after taking them on a steam-yacht tour of Lake Jessup—also operated a sanitarium in Clifton Springs, New York, where the healing power of its sulfur springs attracted patients that included several of their neighbors on Lake Charm.

In 1887, Theodore and Edith had a daughter. Mead, however, had desperately wanted a son and wrote his parents shortly after the baby’s birth that “at present I don’t want to see her or hear her or have anything to do with her.” Soon, though, Mead was doting on the little girl, named Dorothy. But she contracted scarlet fever at age 4 and died. The Meads would have no other children.

Following this devastating loss, Mead spent even more time gardening. He ordered palm seeds from England and Italy and patiently waited years for them to germinate. By 1894, he had as many as 250 palms in pots. But he gave up on palms after losing them all in the Great Freezes of December 1894 and February 1895.

Mead did, however, deduce that overhead irrigation of citrus trees could protect fruit from freezing by covering it with an ice cocoon. Using a pump and irrigation system of his own design, he saved an acre of oranges in this manner and pioneered a technique that has continued to be used by growers today.

Still, Mead’s interests turned increasingly toward flowers. His approach to hybridization was to create new types of plants that combined beauty and commercial value—whether the process was difficult, as with orchids, or simple, as with daylilies.

“He would just give plants away to anybody,” says biographer Paul Butler, author of Orchids and Butterflies: The Life and Times of Theodore Mead (2017, Red Hen Press). “People would come from miles around to see his home and his plants. They’d admire a flower and he’d just say, ‘Go ahead and take it.’”

According to horticulturist Henry Nehrling, who then lived and worked in Gotha, his friend and sometime collaborator was a more accomplished hybridizer of plants than the much better-known Luther Burbank. So it’s no surprise that the grounds around Wait-A-Bit became a wonderland of exotic plants that included a variety of succulents and cacti.

Mead also took an active interest in the young people of Oviedo, many of whom affectionately called him “Uncle Teddy.” With his jolly demeanor and white beard, the botanist played Santa Claus in local Christmas pageants and became the city’s first scoutmaster. Edith, meanwhile, taught sewing classes, gave piano lessons and was a founder of the Oviedo Woman’s Club.

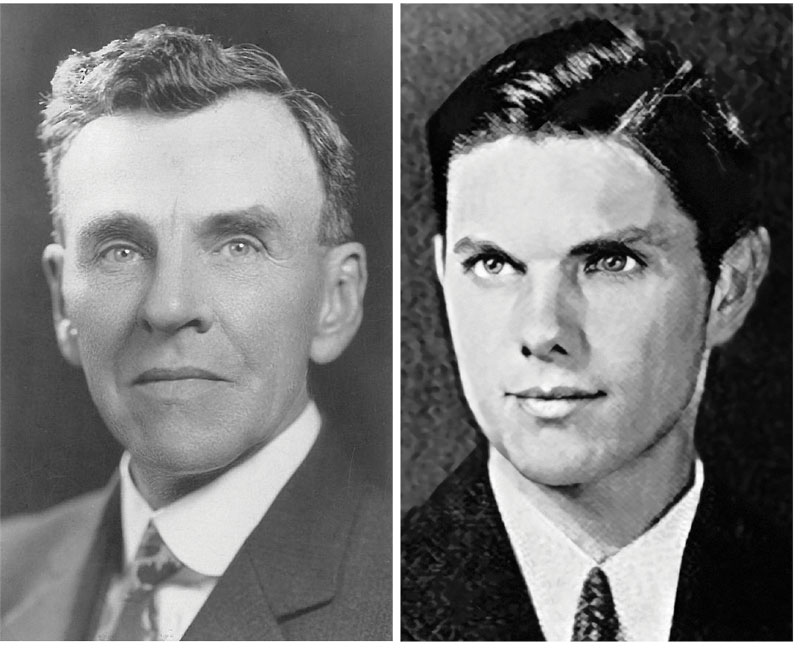

It was through the Boy Scouts, at a 1922 regional camp near Silver Lake in Sanford, that Mead met Jack Connery, a student at Orlando High School and a member of Orlando’s Troop 5 who would soon come to be regarded by Mead as the son that fate had denied him.

Just two years prior, Connery had moved with his family (which included his parents, four brothers and a sister) to Orlando from Chattanooga, Tennessee. Hone Connery, the brood’s patriarch, operated a photography studio on West Colonial Drive.

“Mead was a popular visitor [in scout camp] that year, energetically leading campfire singing and storytelling,” wrote Butler in A Life Touched by Nature: A Biography of Jack Connery (2022, Red Hen Press). Connery later visited Mead in Oviedo and received a tour of his greenhouse filled with orchids and other semitropical treasures.

Scouting also introduced Connery to another life science discipline, ornithology (the study of birds), when William F. Blackman, a former president of Rollins College and president of the Florida Audubon Society, addressed a scout gathering.

Connery’s interest was further piqued by his scoutmaster, Oscar Bayard, himself an accomplished ornithologist. Bayard took Connery—who in 1924 became an Eagle Scout—on several wilderness excursions to hunt for rookeries. He learned how to identify birds and their nests and the protocols for photographing eggs.

Indeed, Connery’s interest in the natural world knew no bounds. In 1930, he traveled to New York to seek out William Beebe, a celebrity naturalist and bestselling author affiliated with the New York Zoological Society. The enthusiastic 21-year-old persuaded the famed adventurer to designate him as the official photographer for an upcoming expedition to investigate marine life in Bermuda.

Adding to Connery’s excitement: During the six-month trip, Beebe planned a record-setting ocean descent in a newfangled bathysphere alongside engineer Otis Barton, who designed the metal vessel. Connery did, in fact, travel with the expedition and documented the historic dive. His photographs later appeared with an article written by Beebe in National Geographic.

In an account that later appeared in the Orlando Sentinel, Connery—who dove several times but not in the bathysphere—wrote: “I would never miss an opportunity to walk on the ocean floor; for the thrilling experience is unlike anything I could have imagined and leaves me unsatisfied in that longing for adventure and research that gets into a fellow’s blood and stays there.”

Certainly, life must have seemed tame back home in Orlando, where Connery gave presentations to schools and civic groups and pondered his future. How about college? The young adventurer had no money but in 1931, bartering for tuition, he donated his collection of birds’ eggs and nests to the Thomas R. Baker Museum of Natural History at Rollins.

While acting as student curator for the museum and teaching classes on ornithology, Connery formed an Explorers Club that garnered newspaper coverage when its members uncovered mastodon bones at Bon Terra north of Flagler Beach.

Most consequently, though, the intrepid overachiever renewed his acquaintance with Mead—now a widower—and helped at his greenhouse as a warm friendship developed. Connery left Rollins without graduating in 1933 and married a fellow student, Helen Galloway, the following year.

But the couple continued to visit Wait-A-Bit as often as possible. Helen, an aspiring writer of fiction, was permitted by the aging botanist to copy his diaries, letters and records about the parentage of his orchid hybridizations.

“Someday,” Connery told Mead, “I’m going to build a memorial garden for you.” Mead was surely flattered but could have had no idea that the well-traveled nature enthusiast—alongside Rollins Professor of Books Edwin Osgood Grover—would do exactly that. Regardless, the pie-in-the-sky project’s namesake wouldn’t live to see it come to fruition (or, more aptly, to bloom).

Mead, now in his 80s, was clearly failing. An admiring colleague, horticulturist Julian Nally, made the pilgrimage to Wait-A-Bit in 1932 and found the property to be “a tangled ruin” overgrown with plants of every description. But he viewed Mead’s disheveled appearance with even more alarm. Recalled Nally: “He had on a [knitted] cap, the jacket of a Boy Scout uniform and a pair of shorts over long wool underwear.”

When Mead was killed by a massive stroke in 1936, a headline in the Orlando Sentinel read: “Science Loses T.L. Mead—Well Known Oviedo Botanist Dies.” His legacy, according to Butler, is perhaps most significant in the development of the ornamental horticulture industry through his work to advance orchid-seed germination techniques.

He also created hundreds of new orchids—almost all forgotten today, says Butler—and his work with Nehrling led to the bicolored Mead-strain amaryllis. All strap-leaved caladiums owe their origin to Mead’s efforts and as an entomologist, he discovered many species of butterfly.

But, perhaps calling upon a degree of false modesty, Mead usually downplayed his achievements. “They call a fellow a wizard if he takes the trouble to cross-pollinate a couple of blossoms,” he once said. “But as a matter of fact, we do nothing more than the farmers who drops seeds in the furrow.”

Elaborated Mead: “We merely do systematically what the bees do for farmers instinctively and haphazardly and what the wind does because it cannot help it.”

SCHOLAR AND SCOUT

After Connery enrolled at Rollins in 1932, he met Grover, likewise a friend and admirer of Mead’s who had visited his home in Oviedo. Grover’s brother, Frederick, was a professor of botany at Oberlin College and the siblings had, coincidentally, discussed ways in which the increasingly frail botanist’s legacy might be preserved.

But Mead had willed his massive collection of orchids, caladiums and amaryllis flowers and bulbs to Connery. Although Grover had sought in vain to acquire the estate and its contents for the college, which would in turn transform the property into a world-class arboretum that could be run by his brother, it now only made sense that he collaborate with his former student to create a memorial garden.

Grover, born in Mantorville, Minnesota, in 1870, was raised in Maine and New Hampshire. While attending Dartmouth College, he worked as a reporter for the Boston Globe and edited the Dartmouth Literary Monthly. After graduation, he briefly attended Harvard but left and embarked on a nine-month journey through Europe and the Middle East. He later boasted that he had spent less than $400 on the whole adventure.

Upon his return, Grover became a textbook salesman for Ginn & Company in the Midwest and was shortly thereafter named chief editor of Rand McNally in Chicago. He later bought controlling interest in the Prang Company, a manufacturer of crayons and watercolors, and relocated the company from New York to Chicago.

Finally, after what he described as “serving a sentence of [almost] 30 years in the publishing business,” Grover was ready to retire. In 1926, however, a call from Rollins President Hamilton Holt prompted a change of plans. Holt wanted Grover as the college’s “professor of books,” making him (or so Holt proclaimed) the first academic in the U.S. to hold such a title. It was arguably the best hire ever made by Holt.

Grover helped students publish the college’s first literary magazine, Flamingo, in 1927, and for the next two decades was “editor” of the college’s Animated Magazine, which was not a published work but a series of lectures featuring national figures from politics, literature, the arts and even show business. He established the first bookstore in Winter Park, The Bookery, and began a boutique book-publishing venture, the Angel Alley Press.

In addition, Grover worked to improve racial inequities within the persistent confines of institutionalized segregation. He served as a trustee of Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach and was a mentor to folklorist Zora Neale Hurston, who dedicated two of her novels, Moses, Man of the Mountain and Jonah’s Gourd Vine, to Grover and his colleague, Rollins theater professor Robert Wunsch.

Grover also encouraged his wife, Mertie—who had been the principal of the Beach Institute, an African American school in Savannah—to help establish a day nursery for the children of working mothers on the city’s west side: The Winter Park Day Nursery for Colored Children (which is today called the Welbourne Nursery and Kindergarten).

After Mertie was struck and killed by a passing vehicle in 1936, Grover raised funds in her memory for the West Side Community Center, the Hannibal Square Library (which closed in 1979 when a new city library was built on New England Avenue) and the Mary Lee DePugh Nursing Home (which is now The Gardens at DePugh on Morse Boulevard).

But past accomplishments aside, the adventurer and the intellectual had a garden to build. Where could such a project be realized? Connery knew just the place. Near the college, he told Grover, was a low-lying area along Howell Creek that he believed would be ideal. The land even encompassed a rookery, he hypothesized, because he had seen hundreds of birds swooping toward the interior every afternoon.

The next morning Grover and Connery, accompanied by Robert Mitchell, a horticulturalist, chopped their way through the underbrush and discovered a small lake which was, as Connery had predicted, near a rookery filled with nesting herons and egrets. Deciding that this all-but-primal tract was, indeed, the ideal place for their nascent venture, Grover set out to secure donations of land.

In May 1937, a new private nonprofit, Theodore L. Mead Botanical Garden Inc., was formed to solicit property owners and to shepherd the staggeringly ambitious project. Elected officers were Robert Bruce Barbour, an industrialist, president; and Raymond W. Greene, a Realtor and city commissioner, first vice president. (Barbour occupied Casa Feliz, now a museum and events venue, while Greene would become mayor in 1952.)

Other officers included Isabella Sprague-Smith, an artist and educator, second vice president; and Harold Mutispaugh, a purchasing agent for Rollins, treasurer. (Sprague-Smith had founded the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park in 1936, while Mutispaugh, who was likely recruited for his financial expertise, would become a city commissioner in 1961.)

Connery, the executive secretary, was the only officer entitled to compensation since he was to supervise the project under the guidance of Grover, who had just been appointed vice president of the college. Later, with the blessing of Holt, his indispensable administrator also became president of the nonprofit.

There seems to have been some sort of contract between the city—which held the donated property in trust—and the nonprofit for supervision of the garden’s development and, once complete, for its ongoing administration. But such a document, informative as it would have been, could not be located by Winter Park Magazine.

Subsequent confusion about ownership was understandable. It was, after all, the nonprofit, not the city, that assembled the land, helmed the transformation and ran the garden on a relatively self-sustaining basis for nearly 20 years. The city—apart from the donation of a few lots and the granting of its imprimatur—was largely a passive player from the beginning.

This might explain, in part, the bitterness that would become evident in the 1950s, when the city moved to consolidate control of the garden and to remake it in ways that strayed significantly from its original purpose. The founders would come to feel that such meddling was not only misguided and destructive but also indicated ingratitude for their years of herculean effort.

But those contentious times were yet to come in 1937, when Grover visited the Angebilt Hotel offices of Walter W. Rose, a developer and state senator who owned 20 acres buffering his new subdivision, Beverly Shores. Undoubtedly, Rose had already reasoned, proximity to a botanical garden instead of a swamp could only enhance the value of his homesites.

Still, the man whose slogan was “Rose Knows Where the Money Grows” did not capitulate immediately. “Those are good building lots, worth $1,000 apiece,” he insisted, although he probably knew better, to Grover. The unflappable professor, who was an effective fundraiser for the college and remembered more than a few tricks from his early career in textbook peddling, was having none of it.

“They don’t look like it to me!” retorted Grover. “They’re too near the railroad. Besides, you want to have an Orlando entrance to the garden, don’t you, so that your people from Beverly Shores can have easy access to it.” Grover later referred to the time he spent haggling with Rose as “the best afternoon’s work I ever did.”

(The garden’s southernmost two acres were then in Orlando, not in Winter Park, with the Orlando entrance proposed for Beverly Shores at what is now Nottingham Drive. Although it is now unmarked with no parking area, this easy-to-miss “unofficial” entrance still offers access for walkers and bicyclists. Winter Park annexed the property in 1955.)

A Jacksonville beauty operator, Mary Bartels, was persuaded to sign over more than 15 acres of inherited pineland that now encompasses the main entryway and the Legacy Garden. Her motives for doing so remain unknown, although it may have been for tax reasons. “Jack and I made two trips to Jacksonville to see her,” wrote Grover, “not finding her at home the first time.” (Why they hadn’t simply called ahead was unexplained.)

James A. Treat, a former Winter Park mayor, contributed another six acres that included the heretofore hidden lake, which he insisted be named “Lake Lillian” for an undoubtedly grateful granddaughter. Smaller parcels, including 1.9 acres owned by Orange County and used to extract clay for road-building projects, were secured and helped to complete the puzzle.

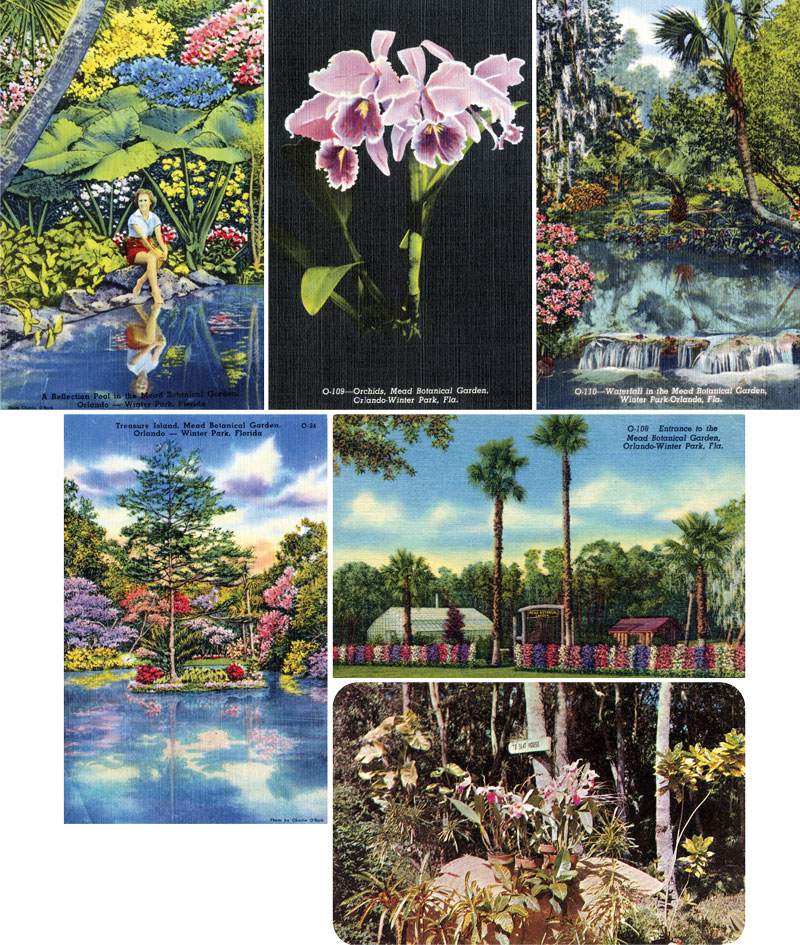

Now, with a site cobbled together, there remained considerable (and costly) work required to transform it into a proper garden. The tentative plan—much of it aspirational—called for miles of shaded trails, several greenhouses for exotic plants, an arboretum for native and imported trees and shrubs, and an aviary that would allow visitors to study bird life in a seminatural setting. There would, hopefully, even be an outdoor saltwater marine aquarium.

How would this all be paid for? Again, the ever-resourceful Grover suggested a way forward. Because the land was deeded by donors to the city, not to the nonprofit, the garden was a public project eligible for grants from the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The New Deal agency initially supplied $20,170 (the equivalent of about $450,000 today) to get things moving.

Awkwardly, however, the grant required that the city contribute matching funds—which it was unable to do. Connery, though, saved the day when he donated an assortment of palm trees and Mead’s plant collection, which was valued at more than $20,000. The agency agreed that the donated plants could be used in lieu of additional cash. Still, federal money could not be used for supplies and materials, meaning that the financial situation was always precarious.

Grover, then, came up with the idea of issuing “revenue certificates” for materials purchases. The certificates—which came in increments of $25, $50 and $100—offered 2 percent interest per year and matured following 10 years, at which time they would be repaid from gate receipts. Initially, the admission fee to the garden was to be 25 cents and gradually ramp up.

Many businesses gladly accepted the highly speculative notes, including a local truck dealership that provided a used vehicle for hauling trees and shrubs. In addition, a timely supplemental grant, this one for $42,000 (the equivalent of more than $920,000 today) was awarded in early 1939 by the WPA.

All the while, workers—under the supervision of the indefatigable Connery—fenced the property and built two landscaped entrances, one in Winter Park on South Pennsylvania Avenue (now a gated back entrance) and the other in Orlando, on Beverly Shores property donated by Rose. Wrote Butler: “[Connery] was immensely popular with all the workers, with his enthusiasm, personal warmth and friendliness, and was universally known as ‘Jack.’”

Swiftly flowing Howell Creek was deepened between Lake Sue and Lake Virginia, a distance of more than a mile, and three waterfalls were created along the route. Through dense undergrowth, three miles of sawdust-covered clay trails were built, while a winding half-mile trail was added along the creek from Lake Virginia to Pennsylvania Avenue.

Two greenhouses sheltered a selection of Mead’s plants, while a broad, sloping area was cleared in preparation for an amphitheater (which wouldn’t be built until 1959). Azaleas, daylilies, amaryllis, gladiolas, caladiums and gardenias were planted everywhere, along with hundreds of palm trees that were hauled by Connery to Winter Park from Mead’s property in Oviedo and from as far away as the Everglades.

The garden was open, informally at least, to inquisitive visitors during construction. One of them—who bought ink by the barrel and was perhaps the region’s most formidable power broker—would make the project a cause célèbre at a time when newspapers were the unrivaled arbiters of public opinion.

Martin Andersen was on an afternoon stroll with his two young daughters when he encountered Grover and Connery on the property. “This is the finest thing ever to happen to Central Florida,” Andersen told the duo. “Who is responsible for this?”

Andersen was not only the editor and publisher of the Orlando Sentinel; as luck would have it, he was also an avid gardener and a collector of orchids. Grover and Connery, from a chance meeting, had enlisted an influential patron in this civic heavyweight, who wrote a series of beseeching (and somewhat scolding) editorials all but demanding public support for the effort.

The message, distilled, was this: “If Winter Park and Orlando really desire to have something unique, beautiful and educational, now’s the opportunity.” As a result, about $11,000 (the equivalent of about $250,000 today) was contributed by duly chastened newspaper readers.

HOPE AND HARDSHIP

Mead Botanical Garden officially opened on January 15, 1940, in a formal ceremony that included local dignitaries, elected officials and 3,000 spectators—including both Florida U.S. Senators, Claude Pepper and Charles O. Andrews—as well 20 “hostesses” costumed as Cypress Gardens-style Southern Belles.

That idea, in fact, was proffered by Dick Pope, founder of the iconic Winter Haven attraction that was known for its waterskiing shows and its photogenic antebellum beauties. Pope, who had agreed to function as the garden’s publicity agent free of charge, told the Orlando Sentinel that the job “sort of challenges the spirit of adventure in me and aroused the old fight.”

The ceremonies, mostly speeches, were broadcast live over WDBO. Grover, who emceed the proceedings, invited Connery to share a few thoughts—which is precisely what he did. “This is a great occasion for us all,” he uttered before returning to his seat on the podium. Grover, who was an experienced presenter, noted: “As you can see, Mr. Connery is a doer, not a talker.”

Orlando Mayor Sam Way marveled that “what used to be a city dump is now a bond of beauty between the two finest cities in Central Florida.” Winter Park Mayor John F. Moody agreed and added that much of the work was not yet visible but “will someday be seen in all its glorious beauty.”

Hamilton Holt, who rarely missed an opportunity to rhapsodize and later served as “honorary president” of the nonprofit’s board, noted that “when Orlando and Winter Park get behind anything, it is sure to succeed.” A garden, he added, could never be truly completed but will “go on and on” for generations to come as it changed and evolved.

For years, the garden was indeed one of the most beautiful spots in Central Florida, and a fitting tribute to both the genius of Mead and the determination (and ingenuity) of Connery and Grover, who had—against all odds—managed to build a beacon to botany in a no-man’s-land during a national economic calamity.

Donations of plants came from all over the world, including 10,000 fresh tulip bulbs from Holland. Eventually, shipments of flowers, seeds and shrubs were received from donors in Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Curaçao, Panama, Venezuela and the Virgin Islands.

But Connery—who needed to earn more money and was concerned for Helen, who also worked as a part-time secretary for Grover and been briefly hospitalized for malnutrition—took a prolonged leave of absence in 1941 to oversee landscaping of the barren 60-acre U.S. Army Air Base in Orlando (formerly Orlando Municipal Airport).

Still, the garden benefited when Connery gave the base some 7,500 cubic yards of peat, the removal of which created new two picturesque bodies of water—one now known as Alice’s Pond—near Howell Creek. The water features offered a contrast to the tropical plantings and allowed the display of colorful water lilies.

When the military job was complete, Connery supervised a 1,500-acre farm growing ramie—a plant native to China that produced strong fibers suitable for use in textiles—in Belle Glade. This led to yet another ramie venture in Havana, Cuba, which ended when the project’s funding dried up after the death of the sponsor (oddly enough, the island nation’s minister of education) in 1950.

Connery had likely become interested in ramie because of Brown Landone, a local character about whom surprisingly little has been written. Although he operated a thriving psychiatric practice, Landone was known nationally as a guru of metaphysics and a proponent of self-healing through a quasi-religious movement called “New Thought.”

A Connery neighbor in Virginia Heights, Landone owned a ramie farm in Zellwood and frequently sought investors for his get-rich-quick ventures among Winter Parkers. (Given the labor-intensive process required to extract fiber—a problem Landone thought he had solved with a device of his own invention—ramie never caught on in the textile industry.)

But we digress. Back in Florida, Jack and Helen settled in the Volusia County town of DeLand, where they started a plant nursery and were hired to relandscape DeLeon Springs. Later, they became a major supplier of African violets to retailers such as F.W. Woolworth Company.

But the Connerys retained their connection to the garden and were board members in the convoluted and controversial years of 1952 and 1953. By then, the property boasted a mile of trails, five ponds and plantings of annuals, azaleas, amaryllis, caladiums, camellias, gardenias and Hemerocallis along with hundreds of tropical and subtropical shrubs, vines and trees.

There were also 10 permanent structures, including three orchid houses, a reception lodge and gift shop, and palm-log gatehouses at both entrances. Yet, attendance had been declining for years—most notably in the summers, when many Winter Parkers headed north—and the garden was already falling into disrepair due to lack of funds.

The nonprofit, however, continued to plod along until the city adopted ham-fisted financial leverage to gain full and iron-clad control. In 1952, city commissioners agreed to increase their paltry $500-per-year commitment to $7,500. They offered to re-up the $7,500 for 1953, but only if the nonprofit turned over control of the garden.

Onerous conditions were attached to make certain that such an outcome was assured. First, the city mandated that the garden’s creditors, among them Grover and Connery, who had advanced a combined $23,000, would agree to waive claims to repayment. In addition, the city, not the nonprofit, would collect all gate receipts—which amounted to about $10,000 annually—from that year forward.

These demands were “of humiliating magnitude and disdain for the founders of the garden” wrote Butler in another book, Hope Springs Eternal: A History of Mead Botanical Garden (2019, Red Hen Press). Still, in 1952 Grover and Connery—not wishing to see the garden fail—signed the waivers, as requested, breathed a sigh of relief and hoped that tensions would ease.

Still, the worst was yet to come. In the summer of 1953, the Orange County School Board offered to pay $27,500 for 13 acres of high pine land in the garden’s southwest sector (the Bartels tract), on which it would construct a new junior high school—now Glenridge Middle School—as well as a recreation complex with sports fields, a swimming pool and perhaps a youth center that would be shared with the community during non-school hours.

Now 84, Grover remained the garden’s fiercest defender although he had stepped down from the nonprofit’s board four years earlier. He editorialized in the Winter Park Herald that “today the garden appears headed for legal controversy and destruction” because of deed restrictions and reversion clauses on the donated land that forbade uses other than as a botanical garden.

“It is hard to believe,” opined Grover, “that this attitude represents the spirit or the wishes of the residents of Winter Park.” And yet, city officials did not dismiss the proposal out of hand, instead making a counteroffer of $3,000 per acre for as many acres as the school board needed.

Then the inevitable blowback began, causing reconsideration and recrimination. Ultimately, it was decided that a referendum—which offered political cover to everyone involved—should be held to decide the question: “Do you favor the use of the undeveloped portion of Mead Botanical Garden as a possible school location?”

Grover, who rallied garden supporters in opposition, warned that vandals had already ransacked the garden with impunity and the situation could only be exacerbated by the on-site presence of teenage hoards. In any case, he added, the property in question was worth at least $100,000.

The school board’s “land grab,” as it was labeled in the Orlando Sentinel, was roundly rejected by a tally of 923 votes for and 365 votes against, in December. The result promoted Grover to pen a letter to the editor, which was published in the always-supportive daily newspaper: “Mead Garden has met with many difficulties, but I am certain that its future is all before it—not behind it!”

Still, Grover’s optimism aside, the garden’s situation would get worse before getting any better. Despite this electoral victory, the nonprofit—lacking resources and receiving only token city support—continued to falter and the final outcome seemed inevitable.

Seeing no apparent alternatives, retired U.S. Navy Vice Admiral A.R. “Rocky” McCann—then president of the nonprofit—threw in the towel and asked that the struggling organization be relieved of its responsibility for the garden in the spring of 1955.

City Attorney Webber Haines noted that the city had “a moral obligation, if not a legal one, to accept the offer and certainly it is desirable to see that this property remain as garden property in the City of Winter Park.” In April 1955, via a quit-claim deed and renumeration of $1, Theodore L. Mead Botanical Garden Inc. signed away any claims it may have had on the property or its contents to the city.

But Connery, as should be apparent by now, was not easily discouraged. In a last-gasp effort, he sought to lease the garden from the city and operate it himself, and threatened litigation if his proposal was denied. This proverbial Hail Mary was, indeed, not favorably received, and Connery did not have the resources to further pursue the matter.

Now rendered effectively irrelevant, the beleaguered nonprofit—which was formed with optimism 18 years prior by Grover and Connery—was dissolved with disappointment. (The “city takeover” had been variously reported in the Orlando Sentinel as having taken place in 1951, 1952 and 1953, but some ambiguity seemed to linger. The quit-claim deed, which appeared to make it all official, was not executed until 1955.)

In the aftermath—and despite promises from the city that the garden would finally fulfill its destiny under new leadership—the expanse gradually morphed into a mishmash of elements that included repair sheds for city vehicles and a dump site for construction detritus when local streets were rebricked. Wrote Butler: “The city’s attitude to this once-beautiful garden was loutish and uncaring.”

The greenhouses fell into ruin and, according to alarmed neighbors on the west side of the garden, the clay pit—where, astonishingly, city garbage was being dumped and buried—became infested with deadly coral snakes. (City crews, dispatched to clean out the pit, were pleased to report—to the scant comfort of those who lived nearby—that they had uncovered only nests of rats.)

Wooden boardwalks were left to decay while garden maintenance consisted of mowing over native plants and leaving them unable to naturally grow and reseed. Mead’s orchids were entirely gone; many having died while others were spirited way by visitors. (Rumors persist, however, that a collection of these orchids still exists, albeit hidden in a warehouse somewhere.)

Now operated under the umbrella of the city’s newly created Parks Board (the precursor to today’s Department of Parks & Recreation), the garden no longer charged admission—which, considering conditions there, was just as well. In 1959, in fact, Grover went to so far as to pen an editorial in the Orlando Sentinel headlined “Dr. Grover Deplores Mead Destruction.” Strong words indeed.

Yet, it was not all doom and gloom following the city takeover. The Little Amphitheater was constructed by the Fashion in the Garden Society, a civic group that used the stage for a succession of successful fashion shows. The Garden Drive entry was bricked and landscaped. A new headquarters on a three-acre site was built for the Florida Federation of Garden Clubs.

But community members were beginning to take the city’s laissez-faire attitude to task. In 1960, the Center for Practical Politics at Rollins, headed by political scientist Paul Douglass, issued a blistering report on the situation. Doug-

lass, in his analysis, contended that “petty municipal politics, public apathy and absence of city planning combined to cause deterioration of the property.”

A master plan, one facilitated by a park specialist, should be funded and adopted, added Douglass, who warned that “failure to take this step can be considered a betrayal of public responsibility by those upon whom it is incumbent to act.” But, he added, “the disappointments and defaults of the past confer upon present city leadership the opportunity for high service.”

Such service was not forthcoming. A 1967 master plan, according to the Orlando Sentinel in 1971, “seemed to fizzle out, and an artist’s rendering of an aviary, aquarium and carillon have been relegated to a place behind the files of the parks and recreation director’s office, hidden from view.” Another plan was adopted in 1989 but that one, too, largely gathered dust.

Despite fits and starts of ideas and activity, neither a plan that was truly taken seriously nor adequate funding for a robust restoration ever materialized. By the early 21st century, the property had become not a botanical garden but an oversized and underused municipal park—still breathtaking in places but in a state of inexorable decline.

Butler summed up the situation succinctly in Hope Springs Eternal: “Mead Botanical Garden has been likened to an unwelcome rich little orphan left as a financial liability on the doorstep of the City of Winter Park, and for the bulk of its upbringing with the city it has been treated as such.”

RECLAMATION AND REDEMPTION

The garden needed new energy to revive the vision of its early champions like Grover and Connelly. Enter Friends of Mead Garden Inc., a nonprofit formed in 2003. The grass-roots (pardon the pun) group of concerned citizens, founded by Beverly Lassiter, president of the Winter Park Garden Club, organized volunteers for cleanup duty and advocated improvement plans to city officials.

The new nonprofit’s officers, in addition to Lassiter, included Jeffrey Blydenburgh, Linda Keen and Carol Hille, vice presidents; Bob Meherg, treasurer; and Jan Reker, secretary. The organization’s purpose: “To revitalize the garden in partnership with the City of Winter Park and the community.”

Lassiter and other volunteers went to work and remained undaunted even in 2004 after hurricanes Charley, Frances and Jeanne—three massive storms in six weeks—left the wetlands a mess and blew in more invasive species. The city and the volunteers, for once not at odds, joined forces to clean up the mess.

“The more I walked and climbed and crawled through the debris, the more it became evident that this was an opportunity for a major renewal of the garden” wrote John Holland, the city’s director of parks and recreation, in a 2005 edition of Mead News, a periodical published by the volunteers. Holland—a cooperative and conciliatory figure—added that yet another master plan would soon be underway.

That plan was adopted in 2007. But an economic storm—this time the Great Recession—caused funding for its implementation to be slashed. Still, volunteer “Weed Warriors” and “Butterfly Brigades” soldiered on, mostly on weekends, doing what they could with limited resources and motivated by their hope for the garden’s future.

Gradually, thanks largely to such efforts, locals began to rediscover the natural oasis literally in their own backyards. In 2012, The Grove—an amphitheater that is home to the Florida Symphony Youth Orchestra—was built for about $700,000. An anonymous donor contributed $250,000, the city allocated $200,000 and the rest was raised from individuals, organizations and foundations.

That same year, Friends of Mead Garden—now Mead Botanical Garden Inc. (MBG)—worked with the Department of Parks & Recreation to hammer out a multiyear agreement that essentially turned over operational responsibility to the privately funded nonprofit and its 16-member board. The city, under this agreement, would continue to provide maintenance and other services while leaving programming and planning to MBG.

“For anything to happen, we had to have control,” says Blydenburgh, a retired architect and a founding director of the Friends of Mead Garden. “Previously, we were just a support group. But being a separate entity gave us the authority to shape what the garden was going to be. And I would make the argument that, bit by bit, we’re getting there.”

Of course, the garden will never be as elaborate or carefully sculpted as Orlando’s nearby (and similarly sized) Leu Gardens, which has an annual operating budget of $2 million and, according to Blydenburgh, would cost at least $40 million to replicate. He adds: “There just isn’t the appetite for a project of that scope in Winter Park.”

But MBG does what it can with what it has. Most notably, in 2012 the late Randy Knight, previously owner of Poole & Fuller Garden Center, headed a project to rehabilitate the dilapidated greenhouse—the symbolic heart of the garden—with fellow volunteers Alice Mikkelsen and Ann Clement, who had previously led a team to restore the Butterfly Garden.

Another pivotal year in the garden’s renaissance was 2017, when legendary photographer Clyde Butcher—whose haunting black-and-white landscapes of the Florida Everglades are considered artistic masterpieces—agreed to bring his camera to the garden. He produced a stunning series of images that caused many viewers to take a second look at a place that they had, perhaps, begun to take for granted.

While he was in town, Butcher headlined a $100 per ticket fundraiser dubbed Lens Envy: An Evening with Clyde Butcher, at the Winter Park Civic Center on New England Avenue. The event, which quickly sold out, featured the amiable artist discussing his career and projecting images of his work. Butcher heartily endorsed the garden’s combination of untamed natural areas with “controlled spaces” that appeared well tended.

“You need to protect what’s in your own backyard,” said Butcher, then 75, a white-bearded happy environmental warrior known for wading waist-deep into alligator-infested muck to get just the right shot. “I would advise people who visit not to rush through it. Go slow. Watch what happens. You could easily spend a whole day and when you come back next, it’ll be an entirely new experience.”

Mead Botanical Garden, which began with such promise, has over the past decade been revitalized in a way that would have pleased (or, more likely, simply pacified) Grover, who died in 1965, and Connery, who died in 1978.

Even Mead, all modesty aside, would surely be gratified that the garden named in his honor was rescued by everyday people who simply loved nature. (He would undoubtedly ask, however, where his orchids had been hidden.)

Although Connery eventually moved past the disappointment, Grover relocated to Garden Acres, the subdivision developed across Denning Drive from the land to which he dedicated the second half of his long life. The venerable professor continued to seek white knights who shared his opinion that the garden was misused and were willing to help make it right.

Unfortunately, the scholar and the scout are today largely forgotten. In 1961, a “Grover Trail” was dedicated and marked with a modest plaque that provides no background or context. Why, a recent visitor asked, was there a trail named for the beloved blue monster from Sesame Street?

Connery, the equally important co-founder, fares even more poorly in the on-site recognition department. His name, unlike Grover’s, isn’t affixed to anything in the garden. In fact, until Butler’s recent book, no in-depth research had ever been conducted on Connery’s colorful life and significant accomplishments.

This just won’t do. Some sort of fitting (and overdue) installation—even an inexpensive explanatory sign—could and should commemorate both men and explain their historic importance. Hopefully, as they plan further improvements, MBG can consider how they might correct this relatively easy-to-remedy oversight.

As part of the garden’s continuing anniversary commemoration, the staff is collecting testimonials and memories to be used in a yet-to-be-determined tribute. To share your memories and photos, send them to info@meadgarden.org. And, most importantly, let’s take a moment to remember with gratitude everyone who made it possible to have such memories to share.

HIS TRILOGY OF BOOKS OFFERS A DEEP DIVE INTO MEAD HISTORY

Paul Butler first set foot in Mead Botanical Garden in late 2009, slipping through the little-used pedestrian entrance on South Pennsylvania Avenue. A retired professor who had recently relocated from England, Butler was an avid horticulturalist and was curious to see this 48-acre urban oasis, which was named for arguably the most skilled hybridizer of plants who ever lived.

“The years had not been kind,” says Butler, who taught materials science at Imperial College and the University of Oxford. So he joined a small army of volunteers under the auspices of Friends of Mead Botanical Garden Inc. (now Mead Botanical Garden Inc.). The group managed to rescue the garden from neglect and reestablish it as one of the city’s most important natural assets.

But what about Theodore Luqueer Mead (1852–1936), the garden’s namesake? “I was unable to find much published information about him,” says Butler, who began researching Mead’s life—at first a casual pastime that quickly became an obsession. “I wanted to find the essence of what made him tick.”

Butler credits his interest in Mead to the late Kenneth Murrah, a Winter Park attorney and history buff whom he had seen perform “a short but captivating historical reenactment of Mead” at a meeting of volunteers. “I left with the impression of just having met a fascinating person from the past who had lived in interesting times,” recalls Butler.

The subsequent five-year project undertaken by Butler resulted in the first-ever book about Mead and his (literally) groundbreaking work, Orchids and Butterflies: The Life and Times of Theodore Mead (2016, Little Red Hen Press). It is a monumental achievement within its relatively narrow niche, rightfully placing the low-key Mead among the likes of Luther Burbank in the pantheon of great horticulturalists.

The book, which is dedicated to Murrah, was a labor of love for Butler. Some hard costs were covered by a Rhea Marsh and Dorothy Lockhart Smith Winter Park History Research Grant, which is administered by Rollins College and the Winter Park Public Library.

But with thousands of hours invested—plus research trips to New York, Colorado and West Virginia—Butler is unlikely to come out ahead financially. “With something like this you have to struggle to stay on message,” he notes. “You find a new piece of information and before you know it, you’re off on a tangent.”

Butler found a wealth of material in the Rollins Department of Archives & Special Collections—most notably about 1,000 pieces of correspondence written by Mead to family and friends. Says Butler: “I’d photograph about 50 of [the letters], then spend the rest of the week deciphering and transcribing his distinctive writing style. I would repeat this each week for around two years.”

What truly matters, says Butler, is that at long last proper recognition has been granted to both Mead the scientist and Mead the man. “He was a true gentleman; an old-school gentleman,” says Butler. “He wasn’t a promoter. He didn’t name his creations after himself. That’s the main reason he isn’t better known today.”

Orchids and Butterflies is a fascinating—and undoubtedly long overdue—biography that’s a hefty 358 pages highlighted by dozens of never-before published photographs of Mead and his family, some vividly restored and colorized. Butler’s writing is direct and accessible, which is not always the case with books penned by academicians (particularly, one assumes, academicians with backgrounds in science).

Still, Butler was not yet finished with Mead Botanical Garden or the people who dreamed it up and made it a reality. He wrote a second book, Hope Springs Eternal: A History of Mead Botanical Garden (2019, Little Red Hen Press), after finding a 1995 letter from Helen Connery, wife of garden co-founder Jack Connery, to Donna Rhein, then archivist at the Winter Park Library.

Helen Connery, whom Butler describes as “one of the unsung heroes” of the garden’s founding, told Rhein that she was interested in possibly writing about her years with the garden now that her husband and the other principals had died.

She continued: “I felt that someday someone would be puzzled by all the misconceptions and misinformation—and lack of knowledge—floating around concerning Mead Garden.” Butler was among those puzzled by the lack of detailed information about the garden’s history, hence Hope Springs Eternal.

But the more Butler found out about Jack Connery, the more he wanted to find out. If he was known at all, the enigmatic Connery was known only as the Eagle Scout who inherited Mead’s orchids and joined Edwin Osgood Grover, the local college’s distinguished professor of books, to establish the garden as a tribute to his botanist mentor.

In fact, Connery was also an accomplished ornithologist, archaeologist and marine biologist as well as a visionary whose relentless work ethic allowed him to accomplish remarkable things at an early age. That means A Life Touched by Nature: A Biography of Jack Connery (2022, Little Red Hen) is truly revelatory since it’s essentially all new information.

Butler uncovered Connery’s story through his trademark relentless research and paints a portrait of a larger-than-life character who might have been portrayed as the hero in a pulp adventure novel (or in a comic book) had he not been flesh-and-blood.

In A Life Touched by Nature, the reader is swept along from adventure to adventure, from project to project, in awe of a man who never shied away from a challenge and remained throughout his life the prototypical All-American Boy.

The only significant garden founder that Butler hasn’t written about is Edwin Osgood Grover, and that’s only because someone else beat him to it. Retired psychiatrist Eduard Gfeller, who lived in Winter Park before moving to New Albany, Indiana, released a self-published book, Edwin Osgood Grover: The Business of Making Good, in 2017. Gfeller died in 2022.

Butler lived in Winter Park until early 2020, when the pandemic hit and airport shutdowns appeared to be looming. He and his wife, Jane, returned to England where they still live in Henley-on-Thames. Butler’s trilogy of books (and Gfeller’s book) are available on Amazon.

—Randy Noles

IN BRIEF

Mead Botanical Garden is open daily from 7:30 a.m. to dusk. It’s located north of Orlando, just off U.S. 17-92 in Winter Park. Coming from Orlando, turn right (east) onto Garden Drive just past the Winter Park city limits. Coming from Winter Park, turn left (east) onto Garden Drive, just past Orange Avenue. Garden Drive leads directly to the main entrance. In addition to being a beautifully unspoiled natural area, the garden boasts a number of facilities available for public use. Among them:

The Grove. This multipurpose, open-air venue hosts an array of musical and theatrical productions. It’s a great place to bring a blanket or a lawn chair and watch a performance in the glorious outdoors.

The Little Amphitheater. Built in 1959, the Little Amphitheater has for decades been one of the most popular settings in the region for weddings and other special functions. Outdoor bench seating can accommodate up to 300 people.

Picnic Pavilion. Looking for a place to hold a picnic, family birthday party or class reunion? The newest pavilion, located near the main entrance next to the parking lot, offers a shady setting and several tables.

The Azalea Lodge. This recently remodeled facility is the perfect indoor space for special events. The 2,400-square-foot reception hall, which has a capacity of 175, includes a foyer, a meeting space and a main hall. An outdoor terrace overlooks Alice’s Pond.

The Legacy Garden Wedding Venue. Near the greenhouse is a small wedding venue shaded by massive live oak trees. Plans call for the area around it to be planted with a variety of curated display gardens.

Mead Botanical Garden also has a community vegetable garden, a popular summer camp and a speaker series as well as birdwatching expeditions, guided hikes and such events as GROWvember (a fall plant sale) and the annual Great Duck Derby (the racing ducks are of the rubber variety) which supports the garden’s educational programs. For more information, call 407-622-6323 or visit meadgarden.org.