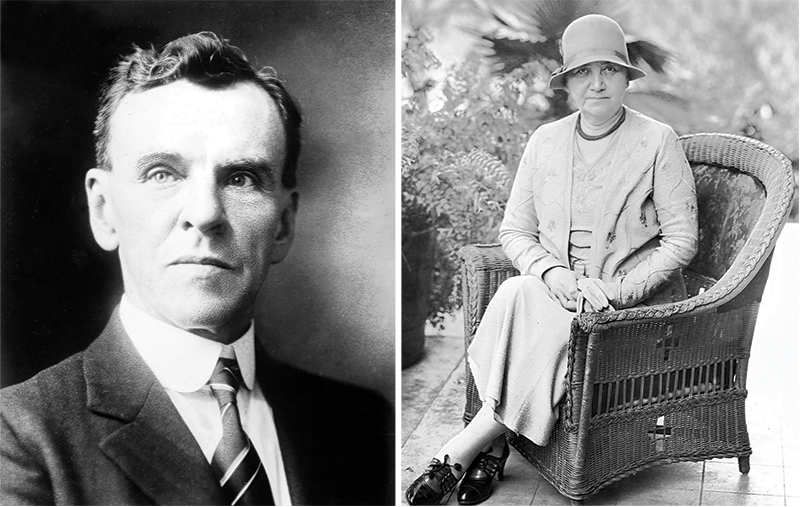

During its 139 years of existence, Rollins College has employed its share of controversial faculty members. But none could match John Andrew Rice Jr., a pugnacious professor of classics who offended the community, divided the campus and enraged President Hamilton Holt.

In 1933, when Holt fired Rice, the iconoclastic intellectual had been accused of traipsing about campus property while clad only in a jockstrap (it was a bathing suit, not a jockstrap, he later insisted), ridiculing his colleagues, damning fraternities and sororities, and “destroying youthful ideals without inculcating anything equally constructive and commendable in their place.”

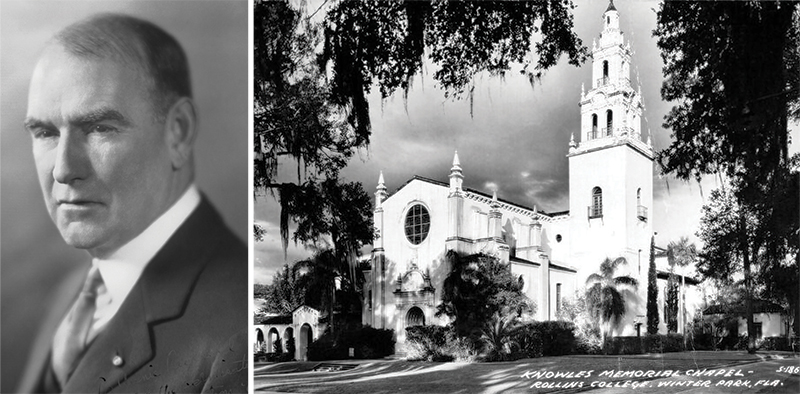

Rice had also ignored the material he was hired to teach—Greek and Latin—and had instead spent class time leading discussions about “irrelevant topics of religion and of sex.” Further, in an act considered by Holt to border on blasphemy, he had openly “scoffed” at services in Knowles Memorial Chapel—and had done so within earshot of the woman who donated the money for its construction.

While these things aren’t entirely true, neither are they entirely false. In any case, one might make the argument that none of these so-called transgressions ought to have been firing offenses at a purported bastion of free speech and intellectual inquiry such as Rollins.

After all, wasn’t Holt a prominent progressive who had himself taken controversial stances and defended the right of others to do so? Yes, without a doubt, he was. But Holt, like Rice (like all of us, really), was sometimes stubborn and wrongheaded. Neither man, in retrospect, behaved in an entirely heroic manner during this collegiate kerfuffle between the president and his tormentor.

Personalities aside, the impact of Rice’s dismissal was significant, ultimately causing the college to be censured by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) and leading to an exodus of eight highly regarded professors—fully one-fourth of the faculty at the picturesque 300-student institution then known informally as “The Harvard of the South.”

Some of those academic exiles joined Rice in founding a now-legendary experimental college near Asheville, in North Carolina’s Buncombe County. Black Mountain College, which operated for 27 years and still stirs the imaginations of academicians, embraced innovation and, for the most part, was governed by the kind of democratic principles that Rice had accused Holt of suppressing at Rollins.

Wherever he went, turmoil followed Rice, who was described as witty and engaging when he chose to be, but rude and sarcastic with those whom he judged to be intellectually lazy or hidebound by convention—populations that included his peers, his bosses, his students and even community supporters of the institutions where he was employed to teach.

In a 1977 oral history, John Tiedtke—who later became an agricultural magnate, a college vice president and a philanthropist who nurtured the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park—recalled Rice as a “very bright and an entertaining conversationalist.” However, continued Tiedtke, “I cannot say that I liked him very much personally, because he was kind of a smart aleck and enjoyed making controversial statements in order to disturb people.”

Holt, who took pride in his congenial (on the surface, anyway) faculty of so-called “golden personalities,” certainly foresaw no tumult when he hired Rice, an opinionated and unfiltered native South Carolinian who was to expose the president’s autocratic streak while testing his tolerance for dissension and disharmony.

The ill-fated relationship began in the summer of 1929, when Rice was on a Guggenheim Fellowship at Oxford University. Holt, who was also visiting England, met with the unorthodox educator at the behest of Rice’s friend (and brother-in-law) Frank Aydelotte, president of prestigious Swarthmore College near Philadelphia.

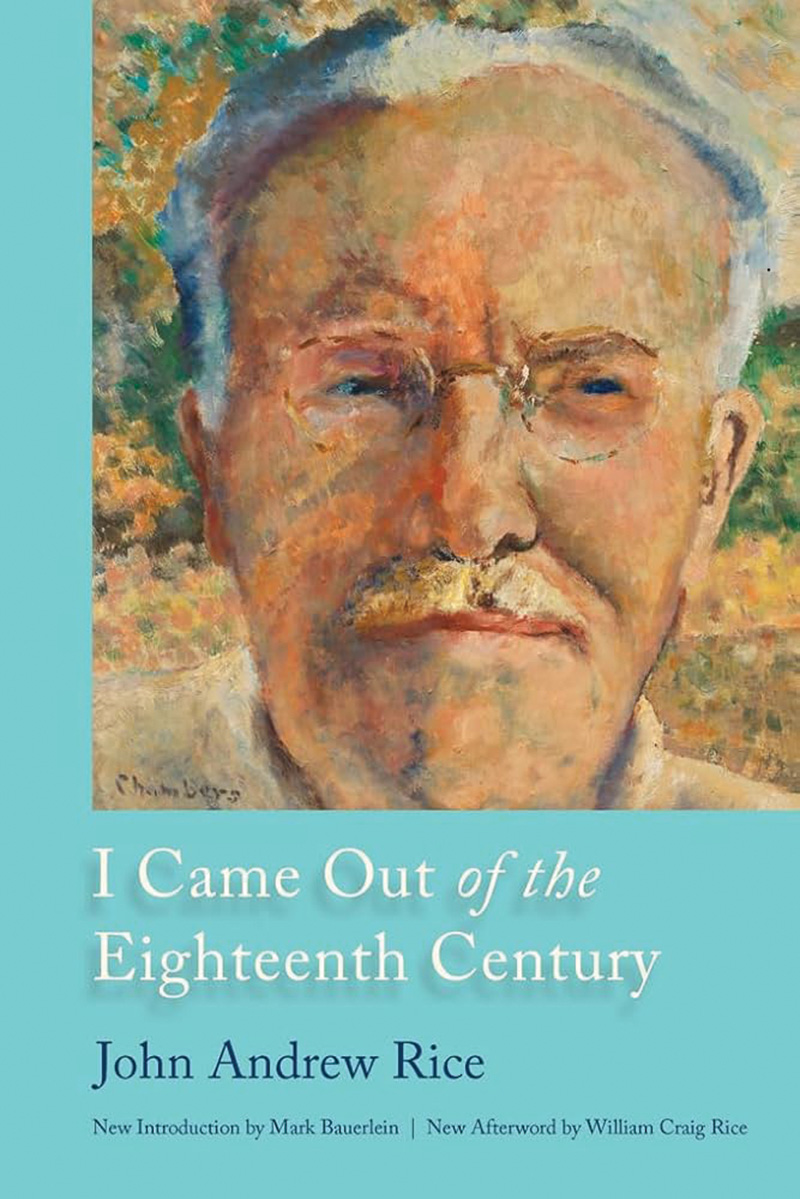

Impressed and intrigued, Holt soon thereafter proffered Rice a position teaching Greek and Latin in Winter Park. “I think it’s about time I had a liberal on my faculty,” said Holt, according to an account by Rice in his autobiography, I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century, first published (and quickly quashed) in 1942. “I haven’t got one now.”

(Holt was being facetious; his faculty included several notable liberals, including attorney Royal Wilbur France, a professor of economics who advocated for free speech and would later become chairperson of the Florida Socialist Party.)

“I had gone to England the year before in doubt as to whether I should ever teach again,” wrote Rice. “But when a letter came from Hamilton Holt, asking whether I should be interested in Rollins College, the answer again was ready. I had gone and left my girl, but when she crooked her finger, I came running.”

Indeed, Holt was favorably predisposed toward Rice in large part because of the recommendation from Aydelotte, who could actually have believed that the “smart aleck” to whom his sister, Nell, was married, might be a good fit for Rollins given the college’s growing reputation for challenging educational orthodoxy.

But upon Rice’s arrival at Rollins in September 1930, he spotted a smattering of proverbial red flags. When he presented himself at Holt’s office, he recalled “seeing on the next door a sign that in large letters read ‘Publicity Office.’ I thought, ‘Well, at least there is frankness here,’ and thought no more, at the time.”

Holt, president since 1925, had previously been editor and publisher of a liberal newsweekly, The Independent, and was, in fact, an adept marketer. His sometimes-shameless headline hunting was scorned by scholars, but his proclivity for publicity had succeeded in branding the college as an innovative, student-centered institution.

Rice, though, was already having doubts about all the hype. Admittedly disheveled (as he always was) and heavily perspiring in the searing heat, he claimed to have received an unfriendly reception. Holt’s secretary, wrote Rice, disliked him on sight and immediately “let me understand that something better was expected of professors.”

In any case, the president’s gatekeeper curtly stated, Holt was away from campus and therefore unavailable for a meeting. “Her manner was rigidly correct,” added Rice. “It was the tone of her voice that told me. But I did not hear. I was glad to be there and forgot what I had learned on my first boat trip; that if you want to know what the captain is like, the manners of the cabin boy will tell you.”

Later, while exploring his new hometown, Rice noted its air of languid affluence (which he took to be synonymous with pretension) and its profusion of churches. Absent any evidence except instinct, he also passed harsh judgment on the city’s populous of “second-class rich folks” whom he assumed held sway over the college and Holt.

On Interlachen Drive he observed “one over-length Lincoln after the other [rolling] along at a solicitous pace, with windows like the windows of a hearse, giving one full view of untroubled calm within, white hair and white blank faces.” Added Rice: “How, I reflected, was a liberal arts college to live in the midst of this? I was soon to find out.”

SOUTHERN DISCOMFORT

Rice was born in 1888 at the family home, a plantation called Tanglewood near Lynchburg, South Carolina, a state in which he wrote that “there were few or no rich, only the well-born—and they took no risk of contamination.” Although he was under no illusions about the South’s shortcomings and was appalled by its entrenched racism, he loved the culture’s storytellers and colorful characters—many of whom were members of his own family.

“The idea that states have distinctive character is quaint in our hypermobile society,” wrote Rice. “But throughout the nineteenth century, before the New South arrived, southern states had acknowledged social identities. For example, Virginia and South Carolina were considered the only states in which gentlemen resided. The other states remained ‘colonial.’”

Rice, to use his own words, was among the well-born. His father, John Andrew Rice Sr., was a Methodist minister who eventually became president of Columbia College, a women’s liberal arts institution in the state capital—a rough-and-tumble place with muddy streets, clouds of flies and a veneer of gentility that his son described as akin to “an awkward, overgrown village, like a country boy come to town all dressed up for Saturday night.”

Because Methodist ministers are itinerant and required to move every four years, the elder Rice, family in tow, hopscotched from pulpit to pulpit, parsonage to parsonage, in Montgomery, New Orleans, Fort Worth, St. Louis and Tulsa. In Dallas, he was a founding faculty member of Southern Methodist University and taught at its school of theology for a year before his attempts to reconcile evolutionary theory with biblical creationism ruffled so many feathers that he had to resign.

His son’s memories of his restless, black-bearded father were generally not fond. “Occasionally, [my father] tried to play with us, but it usually ended in tears, for he did not know how to play, with us or in any way at all,” wrote Rice. “A caress was a blow, and when he tried to tease, we slunk away in shame at his clumsiness.” He thought little better of the church in general, which he later described as “the most regressive institution” in the South.”

Rice’s mother, Annabelle Smith, was the sister of Ellison Durant “Cotton Ed” Smith, a virulent white supremacist who represented South Carolina in the U.S. Senate from 1909 to 1944. Wrote Rice: “[Smith] was an evangelical politician” whose speeches usually incorporated the purity of Southern womanhood and “the white man’s sacred right to lynch.”

Annabelle died in 1899. Two years later, Rice Sr., who had started but failed to complete doctoral work at the University of Chicago, returned to Lynchburg with a new wife, Launa Darnell, the daughter of a circuit-riding Methodist minister and the sister of two Methodist clergymen.

John, then 11 years old, “had read and been told the usual stories about the cruel stepmother—she was always cruel.” He was relieved, however, to find that his own stepmother was kind and caring. (Launa also had a master’s degree in education from the University of Chicago, where she met her husband-to-be, and would later establish one of the country’s first Montessori schools.)

Now with full charge of three children, all boys, Launa encouraged her precocious if peculiar stepson to attend the Webb School, a highly regarded college-prep boarding school in the tiny town of Bell Buckle, Tennessee. She was acquainted with the co-founders, brothers W.R. “Sawney” Webb and John M. Webb, both graduates of the University of North Carolina.

The Webb School was known for turning out a notable number of Rhodes Scholars as well as future luminaries in business, law, medicine, politics, science and the arts. During his time there, from 1905 to 1908, Rice was inspired by John “Old Jack” Webb, whom he would credit for many of his own views on teaching and learning—with the notable exception of the “gentle” part.

“Webb used to sit talking to himself and trimming his grey beard with pocket scissors,” Rice told Time magazine in 1940. “He taught Greek, English, history, math, everything—sitting in a split-bottom chair and gently posing riddles to his pupils.”

Rice then attended Tulane University (his father was serving as pastor of Rayne Memorial Church in New Orleans) where he graduated in just three years. “The diploma said I was a baccalaureus artium, and when the president handed it to me, he welcomed me into the ‘company of educated men,’” wrote Rice. “They were both liars. I had no art, and if I was an educated man, the words meant nothing.”

The Crescent City—with its oppressive humidity, above-ground cemeteries, strained levees, multicultural population and houses of ill repute—had fascinated but repelled Rice, who wrote: “The casual visitor goes back home and tells of the breathless gayety (sic) of New Orleans. If he had stayed a little while, he might have known that it was the cheerfulness of a sanatorium, where death hides in tubercular laughter.”

Degree in hand, Rice—in the grand tradition of Webb School alumni—won a Rhodes Scholarship. While studying jurisprudence at Oxford University, he met Frank Aydelotte—then a professor on leave from the University of Indiana—and Aydelotte’s sister, Nell, whom he wed upon graduation in 1914.

Rice began his teaching career at the Webb School but left after a year to pursue a doctorate in classics (never completed) at the University of Chicago. Nonetheless, he secured a position as an instructor in Greek at the University of Nebraska, where he, Nell and their two young children lived from 1920 to 1927.

Although Rice respected Chancellor Sam Avery—who, he observed, evidenced “a kind of gritty shrewdness” in dealing with regents and donors—he had only contempt for the university’s curriculum, which he compared “to a cafeteria table, except in the proportion of unpalatable dishes.” The university, he believed, “was not superior to high school, but in some respects inferior.”

Still, Rice was popular with students for his freewheeling classroom style, which favored the discussion of ideas over the memorization of facts. Not surprisingly, however, he won very few friends among other faculty members, many of whom he judged to be “incompetents, misfits, trash, and the intellectually lazy.” And he wasn’t shy about sharing this observation freely.

Avery, according to Rice, tried to tame him—or at least to prevent him from sabotaging his own career. “Why don’t you keep your mouth shut, Rice?” asked the exasperated chancellor, who genuinely liked his brilliant but blustery campus curmudgeon. “If you would just keep it shut for, say, six months or a year, I could raise your salary.”

Discretion, though, was simply too much to expect. When Avery, his powerful protector, retired due to ill health, Rice was shown the door. Then, after two years at the New Jersey College for Women (now Douglass Residential College at Rutgers University), he was forced to resign after again antagonizing administrators and colleagues.

In typical Rice fashion, he blamed his troubles on inferior intellects who failed to understand him. In I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century, for example, he described the dean in New Jersey as “an energetic butter-and-egg woman” who had been a poor student and founded the college primarily to exact revenge on professors.

Undeniably, Holt failed to conduct routine due diligence before hiring Rice. But even if he had realized how difficult a character he had taken on, it might not have made any difference. Holt, too, despised uninspired teaching and had condemned the lecture system—which he had endured as a student at Yale and Columbia—as “probably the worst scheme ever devised for imparting knowledge.”

Further, the genial administrator may have reasoned that the pacifying of eccentric professors was his specialty. After all, his lakeside campus dotted with new Spanish Mediterranean structures (the result of an expensive building spree) was something of an oasis for strong-willed intellectuals—and, from all outward appearances, he enjoyed their respect as well as their affection. Some of them even called him “Hammy.”

High-profile activists such as France, the socialist—who wrote that “being a college professor with liberal views in a place like Winter Park was not all honey and roses”—had indeed found a friend in Holt, a national figure who had been a crusader for world peace and who always seemed to strike a balance between supporting academic freedom and pacifying conventional and conservative locals.

But France, like Holt, was at least a gentlemanly sort. Rice, on the other hand, knew—or thought he knew—why he was such a polarizing figure. And, according to an account in I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century, he explained the phenomenon to Holt, who, following their epic clash, had asked, “Rice, why do people hate you so?”

“I think I know the answer,” he replied. “They know that, if I had the making of a world, they would not be in it. They take that thought as a desire on my part to destroy them. I don’t, as a matter of fact, want to destroy anybody, but I suppose the very thought is a kind of destruction, and I can’t blame them for hating.”

RECKONING AT ROLLINS

Not long after Rice’s arrival, when he and Nell settled in a rented house on Ollie Avenue, the outspoken professor began to make his presence uncomfortably felt. During a conference dubbed “The Place of the Church in the Modern World,” which he had been invited to attend, Rice provocatively elected to more specifically question the place of the church in Winter Park.

Addressing a roomful of clergymen, he wondered aloud what the impact might be if all the houses of worship along Interlachen Avenue—including First Congregational Church, which was instrumental in the secular college’s founding—vanished and were replaced by open space. “What difference would it make,” he asked, “and to whom?”

Although the religious leaders sputtered about the worthy causes that their generous congregations supported, none of the answers were adequate for Rice, who concluded that “the white-haired, frightened people of Winter Park” disliked their piety being subject to the “heretical questions.”

Yet Rice had no desire to abolish churches, wrote Thomas Edward Frank, a professor of religious studies at Wake Forest University and a scholar of Black Mountain College, in a 2015 essay for The Journal of Black Mountain College Studies, a digital publication of the Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center in Asheville.

“He was only seeking a searing honesty that ironically would make articulating and holding to an ideal very difficult,” according to Frank. “Indeed, this preacher’s kid’s antennae were always out for any kind of pomposity or inflated notions, which made it almost impossible for him to share fully in any human ideal.”

Even so, Rice’s hostility to overt religiosity hit even closer to home after Knowles Memorial Chapel was completed. Its inaugural Christmas service, which ended with an artificially lighted star that glowed over a darkened sanctuary, was described by Rice—in a voice loud enough for others, including the chapel’s benefactor, to overhear—as “obscene.”

The reason for the outburst, he later explained, was because a nondenominational Protestant service had been conducted in a sanctuary that he had deemed more appropriate for a Catholic mass. Harmony, he believed, required a balance between liturgy and architectural style. Such esoteric logic, however, failed to placate Holt, who considered the chapel to be his crowning achievement and had described it as his “gift to Winter Park.”

Rice, even after his tumultuous professorship had come to an end, continued to ridicule the majestic building in I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century: “A rich woman from Boston gave money for a chapel, had it designed by Ralph Adams Cram, and placed a bronze plaque at the entrance, which said it was erected to the Glory of God—this in small letters—and in the memory of—in huge letters—somebody Knowles.”

“Somebody Knowles” was, in fact, Frances “Fannie” Knowles Warren, one of the college’s most generous philanthropists and a daughter of Francis Bangs Knowles, one of its founders. She and her sister, Mabel Knowles Gage, had given $100,000 toward construction in memory of their father and mother, Hester Ann.

Holt was already prickly about whispered criticisms of the project—mainly from those who believed that the $250,000 (the equivalent of nearly $6 million today) required to build it could have been better spent bolstering the college’s finances and increasing recently slashed faculty salaries.

Rice, upon learning of Holt’s pique, insisted that he was never told about any sort of religious litmus test for faculty members. If the president “had been any kind of judge of men,” he wrote, “he had full opportunity to discover that I was not the kind of man he wanted” when the two met and spoke at length in England.

But criticism of a cherished landmark was not the only way that Rice goaded Holt. His pedagogical approach also caused uneasiness. While he had been hired to teach classical languages, Rice’s students weren’t taught much Latin or Greek. Instead, they were led on intense intellectual tangents that bore little relevance to the published course descriptions.

“[Rice’s] reputation on campus was that he spent most of his [class] time on general subjects such as politics, religion and morality,” recalled John Tiedtke. “He had ways of making statements and cross-questioning students that caused them to get completely confused about the beliefs that they had held when they came to Rollins.”

Challenging preconceptions and honing critical thinking is exactly the way in which the Socratic method (on steroids, perhaps, in this case) favored by Rice was meant to work. Rice, however, found it ridiculous that instruction in classical languages was required to graduate. “This was not the latest thing in education,” he wrote. “It was one of the oldest.”

Still, despite Rice’s increasingly overtly contrarian nature, in 1932 he was asked by Holt to chair a faculty committee that would recommend whether or not fraternities and sororities were compatible with the college’s democratic values. Wrote Rice: “One of my colleagues warned me earlier that if I would be secure, I would stand with fraternities and sororities, especially sororities.”

The warning went unheeded. Under Rice’s leadership, the panel—although not unanimously—called for abolishing the Greek system altogether because it “fostered elitism, exclusiveness, snobbishness, superiority, and promoted an unnatural and unhealthy relationship and even social discrimination.” A predilection for drunken parties thrown by such organizations was also duly noted by Rice.

Holt, a school-spirit booster of the first order, was aghast and chose to ignore the committee’s recommendations. But he surely couldn’t have expected that a group headed by Rice—who had made no secret of his belief that secretive (and rowdy) closed societies had no place in an enlightened learning community—might have reached a different conclusion.

Then in 1933, Rice, along with others on the college’s curriculum committee, proposed a resolution that would abolish the most sacred of Holt’s sacred cows: his highly publicized “conference plan,” which deemphasized lectures and required students, who proceeded at their own pace, to attend three two-hour classes and participate in one two-hour supervised extracurricular activity each day. “Two hours with bores,” wrote Rice, “is at least an hour too much.”

Holt, astonished at this apparent usurping of his authority, refused to budge. He insisted that the committee had been tasked only with recommending how to integrate the conference plan into previously adopted curriculum changes. He threatened to resign (or to dismiss those who opposed him) if a resolution that eliminated his signature program was passed. The proposal was, not surprisingly, indefinitely tabled.

Whatever else Rice was, he was no bore. When this rumpled, pudgy figure who wore thick, round-framed glasses strode to the podium, students didn’t know what to expect—a situation that some loved, while others loathed. But matters became more fraught when donors (and potential donors) began to question the wisdom of employing such a contentious figure.

“Holt was dependent on many of the wealthy residents of Winter Park for funds,” said Ted Dreier, a physics professor who had befriended Rice, in a 1993 interview with Rice biographer and University of South Carolina education professor Katherine Chaddock Reynolds. “And when Mr. Rice didn’t hesitate to say exactly what he thought about things, it caused great hackles and anger among some of the donors.”

John Tiedtke made a similar observation in 1977: “The fact that [Rice] questioned conventional beliefs … caused many people to conclude that he was an atheist, a communist and had no morals. This was not really the case. He was simply enjoying the discomfiture he could cause students by asking them questions which they could not answer. In the community he was pretty generally disliked.”

No single event seems to have led to Rice’s termination in February 1933. After several years of turmoil, the cumulative effect of his presence had simply become too much for a president who valued loyalty and congeniality and wasn’t accustomed to being challenged on policy. “Rice, I have been a liberal all my life and now you have me on the other side,” Holt marveled. “I don’t know how it happened.”

But Rice, to no one’s surprise, refused to accept his firing—or his “non-

reappointment”—without contesting it. When informed by Holt that he was not to return the following semester, Rice asked for another chance, vowing to moderate his behavior and even to consult with the school psychologist, by whom he likely meant Thomas Pearce Bailey, a professor of ethology and psychology and a fellow South Carolinian.

Holt agreed to take a week and think about it. During his deliberations, some progressive faculty members aligned themselves with Rice, even if they held him in personal disdain, as a show of support for academic freedom. Others, grateful to have employment during the Great Depression, tried to steer clear of the impending storm or aligned themselves with Holt.

Many of Rice’s students—who, it should be noted, did not have their livelihoods at stake—were more eager to make his ouster a cause celebre and sent letters in his defense to the man they sometimes affectionately called “Prexy.” Rice, wrote one student, “helped us to develop fine moral characters, to form intelligent philosophies of life which will motivate those beliefs, to appreciate wisdom and to understand art.”

Still others explained that, after being initially intimidated by Rice, they had come to understand that he was, in his unorthodox way, sharpening their minds. “Professor Rice has done more to encourage thought and a search for the truth than anyone else I have come in contact with,” wrote another. “To me, this dismissal is, in a way, symbolic; it expresses the fact that Rollins has given up the fight and is going to become a conventional school.”

Bailey, the psychologist, did intervene on Rice’s behalf, seeking to persuade dubious faculty members that their nemesis had experienced “a complete change of heart” and was “regenerate.” Bailey even composed a cloying letter of apology, ostensibly from Rice, that sought to strike a tone most likely to please Holt.

“I have mistaken license for liberty and incivility for frankness,” read the missive, which sounded nothing like Rice and was almost certainly never used. “I have sometimes forgotten the moral values of conformity. For all these aberrations and more, I am deeply sorry. … I desire to be summarily removed from my office if at any time I seem seriously to have departed from my promise of amendment.”

By the Friday following his first dismissal, Rice wrote, Holt “had by all reports, relented, and I was to see him on Saturday morning.” But on Friday night, Rice continued, Holt shared dinner with Fannie Knowles Warren, the chapel donor, and Irving Bacheller, the bestselling author who had originally recruited Holt. Neither of the president’s dinner guests, Rice speculated, would have been sympathetic to his cause.

“When I stepped into [Holt’s] office the next day his face was grim,” wrote Rice. “He said, ‘Have you anything to say before I give you my decision?’” He did not, replied Rice, “except I think that you are wrong.” Then Holt fired Rice again, this time backed by a resolution of support from the executive committee of the college’s board of trustees. He was ordered to gather his belongings and to vacate the campus within 48 hours.

“When [Holt] dismissed me, someone asked him, ‘How can you do that?’” wrote Rice. “His answer was, ‘Sometimes you have to throw away your principles and do the right thing.’ Freedom of speech offended the white heads of Winter Park, and it was from white heads, nodding toward the grave, that he must get gifts of propitiation.”

COMEDY OF (BAD) MANNERS

The American Association of University Professors had no official standing, as a union would today. But its roster included more than 5,000 members from 200 institutions of higher learning. At the very least, its castigation could cause embarrassment within the world of academia.

Educational reformer John Dewey, who had visited Rollins in 1931 to chair a high-profile conference on the future of the liberal-arts curriculum, had been a co-founder of the organization in 1915. Both Holt and Rice were great admirers of Dewey, who ranked among the country’s most respected scholars.

AAUP general secretary H.W. Tyler had heard about Rice’s dismissal from Swarthmore’s Frank Aydelotte—not from Rice or from another faculty member, as Holt had suspected—but didn’t act since its investigations generally related to matters of tenure. Shortly thereafter, however, when Rice’s formal letter of complaint was received, it accused the college of a tenure violation in his case.

Rice quoted verbatim his offer letter from Holt: “I call you [to Rollins] with the expectation that it will be permanent, but, as I told you, [with] either of us at perfect liberty to sever the connection at the end of one or two years with or without any given reason and no hard feelings on either side.”

Consequently, in May 1933 the AAUP sent a formidable investigative team consisting of Arthur O. Lovejoy, a professor of philosophy from Johns Hopkins University, and Austin S. Edwards, a professor of psychology from the University of Georgia, to Winter Park.

Holt, perhaps realizing that his tenure policy was vulnerable, decided that the hearing should focus on other issues that led to Rice’s dismissal. But, unlike the college, Holt didn’t control the AAUP and found—to his displeasure—that he was in no position to dictate the boundaries of any independent inquiry.

Katherine Chaddock Reynolds, in her 1998 research paper entitled An AAUP Investigation Southern Style: Arthur Lovejoy and the 1933 Rollins Fracas, was unsparing in her description of the fiasco that followed. She wrote: “Undoubtedly much to Lovejoy’s discomfort, the AAUP investigation at Rollins quickly took on a character generally reserved for family feuds in small southern towns, veering from fact finding to tale telling.”

During a hearing held in the vestry room of Knowles Memorial Chapel, Holt read aloud more than 50 affidavits that he and Winslow S. Anderson, dean of the college, had solicited from students, parents, staffers and faculty members who supported the dismissal of Rice.

The affidavits, wrote Reynolds in her 1998 paper, “echoed the gossip broadcast from wooden rockers on wide front-porch verandas” and passed along “third-hand information about who did what and who said what [that] led to a cacophony of personal venting.” Ultimately, this 11-hour spectacle, which Rice described as “a blunderbuss load of hate,” did the president’s case more harm than good.

Rice, accompanied by supporters Ralph Lounsbury, a professor of government, and Frederick Georgia, a professor of chemistry, was taken aback at Holt’s pettiness. “After I had recovered from the first shock, I began to find out how I felt,” wrote Rice. “Holt was determined to destroy me. There was no doubt about that, even if I had been willing to misread the look on his face, whose cruel mouth was matched by cruel eyes.”

But Rice also realized that Holt could not—or would not—attempt to defend the substance of the tenure complaint. Instead he would relate, for example, a father’s complaint that his daughter was subjected to “stinging remarks” in class and “came home in such of state of nervous irritability and so greatly excited that she was not herself at all.”

Or a mother’s observation that her daughter was taught by Rice “that when a student goes to college it is time to break away from the influence of one’s parents, and that the average conventions of life are really nearly all ‘hooey.’” Other parents wrote of similar concerns about perplexing “changes” that they had observed in their youngsters who had “fallen under the influence” of Rice.

Students, at least those who preferred less idiosyncratic professors, also weighed in. One lamented that Rice had “raked me back and forth over the coals and said I was the kind of man that he would like to put out of Rollins College.” A female student quoted Rice as saying, “Do you know what you are? You are something that rhymes with witch. And it isn’t ditch.”

Several students reported having their feelings hurt by caustic remarks and a handful griped (accurately) that due to Rice’s digressions, they hadn’t learned much in his class about Greek and Latin. Wrote one student: “His class seemed to be more of an open forum where economics, religion, world literature, sex, love and everything but Latin was discussed.”

Some professors likewise had their knives out. A math instructor wrote that her students were distracted by the “uproarious” behavior allowed by Rice in an adjacent classroom. When she confronted her colleague, she continued, he “threatened to throw a brick over the partition.” She considered Rice to be insane, but added, “of course, I am not an alienist (psychiatrist).”

A dean asserted that Rice’s “cutting remarks” in faculty meetings had become intolerable and “caused considerable suffering” among attendees. Prior to Rice’s hiring, he wrote, the college enjoyed a faculty and staff of “enthusiastic, harmonious and cooperative workers” who related to one another like members of a family, with only “occasional rifts.”

Rice, who tended toward physical indolence, vehemently opposed the college’s physical education requirement. So it’s no surprise that the director of women’s physical education declared that his criticism of her program “has always been destructive, with nothing constructive to build on. For immature college students to have a leader of this kind is disastrous.”

(Later, in I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century, Rice explained his distaste for physical exertion as a cultural manifestation of his boyhood in South Carolina. “Exercise, if one got any at all, was incidental to something else. As when one shot partridges or ducks. … No lady ever got up a good sweat. Muscle and tan were stigma of low origin.”)

Even a registrar skewered Rice for his neglect of paperwork and his rudeness during staff meetings. She wrote: “I would often return [from meetings] in such a state of resentment that I would say to the girls in the office something like ‘he ought to be punched in the face,’ or something equally violent.”

And there were still more allegations. Rice, it was alleged, had hung self-described “indecent” pictures in his classroom. (In fact, Rice responded, he had displayed innocuous images from a calendar bought at a local drug store to spark a discussion about what is and isn’t art. By calling them “indecent,” he had only meant that they were offensive to his sensibilities, not prurient.)

Further, he had shamelessly greeted visitors to his campus-adjacent home and “disgusted” fellow guests at Pelican House, a college-owned beach getaway, by wearing only a jockstrap in their presence. (Rice had worn bathing trunks, he insisted, and didn’t even own a jockstrap.) And, to make matters worse, he had carelessly left fish scales in the sink of the property at New Smyrna Beach. (Yes, he acknowledged, he probably had if that’s what the housekeeper claimed.)

Most egregiously, he had referred to the inaugural Christmas service at Knowles Memorial Chapel as “obscene.” (Yes, of course he had. Explained Rice: “You can’t put on a vaudeville show, pink spotlight, stunt singing, a choirmaster standing with his back to the altar in a Catholic-style chapel without incurring the charge of obscenity.”)

On and on it went. Rice, it was alleged, had demeaned students he didn’t favor and had allowed those in his thrall to behave in an “eccentric and queer” manner. He had influenced students to resign from fraternities and sororities and had “evidently amused himself by dabbling with the minds and emotions” of his young charges. Holt conceded that he had never actually attended any of Rice’s classes but had heard a great deal about them secondhand.

Although Holt had hoped to avoid the topic, Lovejoy and Edwards did indeed probe the college’s tenure policy, a subject about which they reported that Holt was evasive, contradictory and nonspecific—perhaps because he appreciated his vulnerability on the issue and perhaps because he believed that, regardless of tenure, he had ample cause to fire Rice.

Rollins did have a tenure policy, in which faculty members received one-year appointments with automatic reappointments after three years unless “reasonable notice” to the contrary was given. Holt, however, had long been accustomed to making his own rules. “If I hire a cook,” he later said, “I don’t call a committee of cooks to decide if I should fire him.”

Rice noted that the tenure policy currently in effect had been adopted after he had been hired. His appointment letter from Holt clearly stated that he would be granted tenure after two years—which he had exceeded—not three. In any case, even if he had been terminated for cause, 48 hours could hardly be considered “reasonable notice.”

After eight days of contentious and sometimes comical testimony and commentary, Lovejoy and Edwards had heard quite enough. They thanked everyone for their patience and promised a report as soon as possible. The entire affair, wrote Reynolds, “would mark a low point in the conduct of personnel affairs in higher education.”

A “preliminary report” released while the investigative team was still in Winter Park—and disseminated to the media—found that “the existing rules and recent practice of the college with regard to tenure and to procedure in removal seem to the committee unsatisfactory … and detrimental to the interests of the college.” Rice was still fired—the AAUP couldn’t compel his reinstatement—but the worst was yet to come for Holt.

Stung by Rice and the “rebels” who had supported him, Holt wasted little time in seeking signatures from faculty fellow travelers an oath of allegiance that read: “Will you give your loyalty and support to reducing the [dissension] on the campus and in carrying out policies of the trustees, the faculty or acts by [Holt] or any others in authority even though you may intellectually differ with them?”

Among this cadre of suspected subversives it was Lounsbury, a classmate of Holt’s at Yale, who persuaded his long-time friend to back down. “Look, Hammy, you don’t want to do anything like this,” said Lounsbury. “If you take my advice, you’ll collect these and not let anyone else see them.”

Holt did back down on the pledge as perhaps being a bridge too far for an erstwhile progressive. Still, eight faculty members—including Lounsbury and Georgia, who were described as “disturbing elements” by Holt—were soon fired or had resigned. In the wake of the high-profile faculty exodus, an Orlando Sentinel headline, playing off the “golden personalities” label, read: “Rollins Goes Off Gold Standard.”

Indeed, publications everywhere ran with the irresistible story, which anyone with a background in publicity and journalism, as Holt had, would certainly have expected. Time magazine opined that Holt “seemed doggedly intent on getting his own way even if it meant decimating his faculty and losing leading students. The New Republic observed that “loyalty to Holt is clearly put above loyalty to the individual’s educational ideals.”

Holt surely anticipated a skewering by the AAUP—and he got one. The organization’s final report, released in November 1933 exonerated Rice and censured Rollins, placing the college on the organization’s “unacceptable institutions” list. Holt, it said, had acted in a manner “humiliating to the faculty [and] incongruous with the spirit of cooperation in an educational experiment ostensibly characteristic of the college.”

This report enraged Holt, who loudly contended that the AAUP—especially Lovejoy—was biased against him. But it delighted Rice, whom the investigators described as “a teacher who appears on the one hand to have done more than any other to provoke questioning, discussion and the spirit of inquiry among his students, and on the other hand to have aimed, with exceptional success, at constructive results in both thought and character.”

Tenure issues aside, Rice’s firing probably could have been justified—his refusal to teach the courses that he had been hired to teach would likely have been reason enough. And even the scathing report, while praising Rice’s skills as a teacher, admitted that he had done himself no favors with “frequently vehement, sometimes intemperate, and in several instances discourteous language.”

But Holt’s strategy—to deluge Lovejoy and Edwards in a toxic maelstrom that encompassed both the serious and the silly—demonstrated real malice. Holt actually was trying to destroy Rice. And Rice, although he was unquestionably abrasive and divisive, wasn’t alone in his views about Rollins. A consensus had already emerged even among cooler heads that Holt had simply become too stubborn and dictatorial.

Later, when the college sought to mend fences with the AAUP, Lovejoy—who appears to have been far more indignant over the matter than Edwards, his investigative partner—privately lobbied against reinstatement, writing that Holt was “uniquely misguided, rambunctious and untrustworthy” and had waged a continuing “libelous campaign of abuse and misrepresentation” against the faculty members whom he had dismissed.

“Rollins is Holt and Holt is Rollins” was generally accepted as a statement of fact. But, as Rice never hesitated to point out, that was hardly the mantra of a democratic utopia. Holt, he wrote, “believed, and practice had beguiled him, that if he said a thing three times and nobody called him a liar, then he had spoken the truth.”

When telling him goodbye, Rice recalled, “[Holt] was gracious again; all the hate was gone from his face, except from the hard lines around the mouth. When we had exchanged regrets, it spoke: ‘This thing has cost me at least fifty thousand dollars.’”

Led by the unrepentant Rice, three of the banished professors—among them Lounsbury, Georgia and Ted Dreier—went on to found Black Mountain College. They originally dubbed their venture “New College,” today, coincidentally, the name of an institution at the center of the culture wars in Florida.

“I like the ones leaving better than the ones who are staying,” Holt said, at least according to Rice. But even if Holt never uttered those precise words, there’s undoubtedly truth in the sentiment. The departure of Lounsbury, his long-time friend who died suddenly of a stroke less than a year after his arrival at Black Mountain, must have been particularly painful.

Losing Dreier was also unfortunate for Holt, and for Rollins. Dreier’s family was quite wealthy, and he had many wealthy friends. Among them was Malcolm “Mac” Forbes, a cousin of the publishing entrepreneur, who had been a professor of psychology at the college but had left prior to the controversy regarding Rice.

Together, Dreier and Forbes bailed out Black Mountain several times in the 1930s and ’40s. Dreier’s aunt, Margaret Dreier Robbins—an activist for women’s rights—resigned from the Rollins board of trustees in 1934, after her nephew was fired.

Robbins had suggested that Holt elect a faculty committee to decide Rice’s fate so that responsibility for whatever happened in the aftermath could be shared. Doing so, she pointed out, would avoid a damaging rift on campus and be consistent with his “own liberal policies.” Reasonable as that all sounds in retrospect, it was a message that Holt was unable to hear.

RICE’S GRAINS OF WISDOM

“Poverty is the seedbed of piety.”

“From them I learned what awful things silence can say.”

“When it comes to people, clarity unwed to charity can be an evil thing.”

“A man may remember his childhood with pleasure, but where is the one who does not wince at the memory of his adolescence?”

“There is no way to describe existence. It can only be felt.”

“Every man carries around inside himself two pictures, patterns, ideas; one of the human being he is, one as he ought to be.”

“You cannot change middle-aged men: they have to change themselves, and middle-aged teachers cannot change themselves.”

“A man is a good teacher if he is a better something else.”

“People think they want something new and different, think they want freedom, but what they really want is old things changed enough to make them feel comfortable.”

“The young, the real young, have not yet learned that they have a stake in not seeing the truth.”

“What we are is what we were, changed and added to, but still what we were.”

“I found my way into a Presbyterian church and was amazed to see that a man could praise the Lord without a drop of sweat,

or even perspiration.”

“Of all the arts there was only one, the one that comes to flower in a decaying civilization, and not till then: oratory, the poetry of death.”

Excerpted primarily from I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century.

EDUCATIONAL ADVENTURE

In the meantime, Black Mountain College began inauspiciously. Furnished buildings were rented from Blue Ridge Assembly, a Christian summer camp that was unoccupied in the off-season. (In 1941, the campus was moved to nearby Lake Eden.)

A $10,000 donation—seed money—was made by Mac Forbes and classes got underway in the fall of 1933 with roughly two dozen students, some of whom had come from Rollins, and half as many teachers. A 1936 Harper’s article noted that professors “pooled their personal book collections and called the result a college library.” Rice, who was featured in the magazine, was described as “intelligent, well-informed, fantastically honest and candid.”

That glowing article—and others in the popular press, which usually offered enchanted perspectives about this supposed academic dreamland—generated favorable publicity for the school but angered other faculty members by focusing heavily on Rice, thereby creating a rift that led to the departure of Frederick Georgia.

Rice and his fellow dissidents believed that a college should be owned and run by its faculty and students. There would be no board of trustees, no dean, no president and limited administration beyond a secretary, treasurer and the lead role of “rector”—a position held by Rice—all of whom would teach classes as well.

There was also a “board of fellows” composed of several professors and a student representative that would primarily make business decisions on the college’s behalf, as well as a “disemboweled” advisory council with no real authority, as Martin Duberman describes it in Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community (Northwestern University Press, 2009).

As for the curriculum, there wasn’t one to speak of. Professors taught what they wished, and students graduated when (or if) they wanted. Only about 55 of the 1,200 or so students who attended Black Mountain in its 24-year existence attained a formal degree—as long as they passed two sets of exams, one roughly at the halfway point and the other before the end of their educational adventure.

Students often performed chores as part of the “work program,” with afternoons left free for activities outdoors. Chores might have included chopping wood, clearing pastures and planting, tending or harvesting crops. (Generally, students were poor excuses for farmers, conceded Rice.)

Manual labor aside, among Black Mountain’s most visionary notions was to put art “at the very center of things.” Rice believed that the study of art taught students that the real struggle was, in his words, with one’s “own ignorance and clumsiness.”

But, despite its emphasis on art, Black Mountain was not an art school. It was, instead, “a liberal arts college that placed the arts at the center of the curriculum,” states a description in the Black Mountain Museum and Arts Center in Asheville. “The idea was that, for students across any discipline, the ability to see the world through clear eyes would open up new possibilities of learning and developing as an individual within the community.”

Yet, for his idea to succeed, Rice needed a visionary to head the art program. The problem was, he didn’t know many artists himself. So he went to meet with young Philip Johnson—later a legendary modernist architect but then a curator at the Museum of Modern Art—who suggested Josef Albers, an abstract artist and popular professor at the celebrated Bauhaus in Germany, which was, arguably, the world’s most famous art school.

In 1933, in the face of Nazi harassment, the Bauhaus faculty elected to shut down and refused to comply with requirements for reopening, such as hiring Party members to teach. In addition, Albers’s wife, Anni—a master weaver and former Bauhaus instructor—was Jewish in an increasingly menacing atmosphere.

But there seemed to be one obstacle. “I don’t speak English,” Albers admitted when Rice telegraphed an offer for the couple to join the faculty in North Carolina. Rice replied: “Come anyway.” It’s widely agreed that the hiring of Albers, now regarded as one of the most influential visual arts professors of the 20th century, was Rice’s most savvy move. (The only classes required at Black Mountain were Rice’s course on Plato and Albers’s course on the foundations of art.)

But all this cost money and Rice, by his own admission, was a terrible fundraiser. He wrote: “When I walked into the room of a rich man, I said, without opening my mouth, ‘You’ve got no business with all that money. Now shell it out.’ It never worked.”

As must now be apparent, Rice had more than one fatal flaw in terms of interpersonal relations. These flaws converged in 1940, when he was removed by the board of fellows from his role as rector. “I began to see, but slowly and with reluctance,” he told Time magazine, “that I must live apart from people, for their good and mine. A teacher should bring peace.”

In I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century, Rice discussed his time at Black Mountain in a somewhat cursory manner, perhaps because the events were too fresh for reflection. He did claim that his dismissal was, in part, because the faculty had come to regard itself as a family, and him as the father figure.

“Most of the men [on the faculty] had been unhappy in their childhoods and hated their fathers,” opined Rice, who added that he “knew too much” about their personal lives because they had confided in him. In response, he had spoken uncomfortable truths—and then they had despised him for it.

Despite the internal political turmoil—and the departure of Rice—Black Mountain, while never conventionally successful, grew in stature with its revolutionary approach and its own revolving faculty of golden personalities.

Among the well-known names who had cameos in Black Mountain’s history were painters Leo Amino, Franz Kline, Jacob Lawrence, Robert Motherwell and Ben Shahn; photographers Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind; art critic Clement Greenberg; social critic Paul Goodman; and literary critic Alfred Kazin.

Among the most enduring and evocative images of Black Mountain are several photographs of R. Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller, the eccentric inventor and designer, attempting to construct his first large-scale geodesic dome. (It collapsed, but Fuller was eventually successful.)

That was in the summer of 1948, when Fuller was a faculty member in residence at the school along with Willem and Elaine de Kooning, abstract expressionist painters; John Cage, composer and music theorist; and Merce Cunningham, dancer and choreographer.

Plenty of students, as well, would make names for themselves. Among them were Ruth Asawa, sculptor; Robert De Niro Sr., photographer (and yes, father of that Robert DiNiro); and Francine du Plessix Gray, writer and literary critic.

Other notable students included Ray Johnson, collagist; Kenneth Noland, painter; Arthur Penn, film director; Robert Rauschenberg, graphic artist (and pop art pioneer); Susan Weil, mixed-media artist (and spouse of Rauschenberg); and John Wieners, Beat poet.

Not unexpectedly during the Red Scare of the mid-1950s, the FBI took notice and investigated the school for potentially spreading communist ideology. Agents—whose supposedly undercover presence was, by all accounts, quite conspicuous among the close-knit bohemians of Black Mountain—concluded primarily the obvious.

Black Mountain, according to investigators, was indeed “a very unusual type of school; for example, a student may do nothing all day and in the middle of the night may decide he wants to paint or write, which he does, and he may call upon his teachers at this time for guidance. They advised that everything is left to the individual.”

Was it a hotbed of communism? The FBI report concluded that such an assessment was “indefinite.” In the end, the school found itself, like so many institutions, mired in internal disputes and administrative conflicts. It closed in 1957 for the same reason others have: lack of money.

But its legend lives on. In the end notes of his chapter on Rice in the book Rollins College Centennial History: A Story of Perseverance, 1885–1985 (Story Farm, 2017) professor of history emeritus Jack Lane writes that “the open, receptive venue at Rollins College was one of the few places where progressive ideas were given the freedom to germinate.”

Adds Lane: “Nevertheless, it may be said that without Rollins there would have been no Black Mountain College. Ironically, Holt’s imperious resistance to radical progressive reforms was responsible for the conditions that led to the creation of those reforms elsewhere. Holt seemed to take pride in Rollins’s role in Black Mountain’s success, as long as such experiments occurred some other place.”

NO MORE IDEALS, ILLUSIONS

Although the best college professors teach students to become critical thinkers by challenging them to defend their beliefs and preconceptions, it wasn’t an approach that all professors (or all parents and students) appreciated at Rollins College in the 1930s. At least, they didn’t all appreciate the way the process was undertaken by John A. Rice, the provocative professor of classics.

How did Rice approach teaching? When he was attempting to mend fences and save his job, he visited Edwin Osgood Grover, the professor of books whom he would later ridicule in I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century. But Rice knew that Grover was close to President Hamilton Holt and might therefore be of aid.

Grover recalled the meeting and recounted it in an affidavit used against Rice by Holt in a hearing before an investigative committee of the American Association of University Professors. Here, according to Grover, is Rice’s description of his role as a teacher:

––––––

We then had a very frank discussion of [Rice’s] general philosophy of life, and his acknowledged efforts to ‘remake’ the minds of his students.

He stated that his first effort was to destroy the ideals, illusions and loyalties of the students so as to leave their minds empty. With this accomplished, he could begin to rebuild their minds on the basis of independent thinking and the establishing of their own codes of convictions, morals and loyalties.

I asked him how long a time this process took and he said from a year to a year and a half. I asked him if they all got it in time and he said “No, but if you give me two years I can remake anyone’s life.”

When I asked what happened if, after “emptying” a student’s mind it was not “refilled,” his reply was “he’s out of luck, that’s all!”

RICE’S REVENGE

In the summer of 1940, Rice—now essentially banished from the academic world—started working on I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century, an autobiography that was published in 1942 by Harper & Brothers (now HarperCollins).

The work, which was chosen for the publisher’s 125th Anniversary Prize and was excerpted in three issues of Harper’s Magazine, earned glowing reviews from such national publications as Newsweek, which called Rice “a skilled and deadly writer,” and The Nation, which called the book’s language “vigorous, persuasive and epigrammatic.”

Rice’s magnum opus—as insightful and hilarious today as when it was released—was praised as both a lively and dishy personal reflection from a brilliant but self-sabotaging eccentric and a perceptive insider’s exploration of social conditions and race relations in the Jim Crow South.

But I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century vanished from the marketplace seven months after its initial release when Holt threatened a libel suit and the publisher halted distribution. In a chapter called “Rollins Was Holt,” Rice committed what Holt must have viewed as an unpardonable sin: He portrayed the president as an autocrat and described his college as a decidedly unserious place.

To a modern reader, the chapter reads as funny and caustic—Rice was, indeed, skilled and deadly with words—but hardly libelous. Of particular offense at the time was his mockery of Holt’s tendency to bestow fanciful titles on faculty members and his unflattering observations about the people who held those titles.

Among them was Corra Mae Harris, a celebrated Southern writer who was the college’s “professor of evil.” Harris’s course, according to her own description, examined “the history and philosophy of evil as contrasted with virtue.” However, claimed Rice, the class had met only once, to have a picture taken.

In fact, Harris was an unrepentant racist whose essays should have offended any enlightened person, even by the standards of the day. Holt, in most respects ahead of the curve on civil rights and a founder of the NAACP, not only published her writing—most memorably “A Southern Woman’s View,” which attempted to justify a lynching in Georgia—but also praised it as “genius” when he was managing editor of The Independent.

Surely if Rice had known anything about Harris, he would have used her presence on campus to eviscerate Holt and to ascribe a darker meaning to her academic sobriquet. It certainly would have been uncharacteristic of him to pass over such a tantalizing opportunity. But Holt escaped further embarrassment because Rice seemed unaware of Harris’s previous literary output.

Rice also ridiculed Fleetwood Peeples, a swimming instructor and director of aquatics who was also dubbed “professor of fishing and hunting.” The worst he could say of Peeples was that he was inept at catching speckled perch. Of course, Rice couldn’t have known that Peeples, who also taught swimming to community members, would posthumously be accused by multiple women of molesting them when they were children and subsequently be scrubbed from the histories of the college and the city.

Likewise, Rice lampooned the presence of a “professor of books,” from whom, he mused, he “might learn new uses to which books might be put.” He also questioned Holt’s claim that the college had the world’s only professor of books, pointing out that other colleges had such faculty positions. If so, said Holt, then Rollins had the only Emersonian professor of books.

But while Harris and Peeples were easy targets, Rice missed the mark when he trained his rhetorical sights on Edwin Osgood Grover, the local—if not only—professor of books who created the Animated Magazine for Rollins and spearheaded the creation of Mead Botanical Garden for the City of Winter Park.

Rice claimed that Grover—who had called his antagonist “arrogant and intolerant” in his AAUP affidavit—had been merely a “salesman” for Rand McNally. This was true, as far as it went; as a young man, Grover had sold textbooks for the company. Subsequently, however, he had ascended to the post of editor and vice-president—a professional accomplishment that was notably (and perhaps intentionally) unmentioned.

Rice also stated that, just before being hired by Rollins, Grover had been an “advance agent” for Billy Sunday, a baseball player turned evangelist whose fundamentalism led him to oppose the teaching of evolution, immigration from southern and eastern Europe, and such popular amusements as dancing, playing cards and attending the theater.

No evidence of a connection between Grover and Sunday can be found, although it’s difficult to believe that Rice simply concocted it out of whole cloth. It’s possible, then, that the reporting of this detail was simply sloppy or that the author was simply misinformed. In either case, an irritated Grover insisted that Harper & Brothers remove the allegedly erroneous passage—which the publisher agreed to do in a second edition.

But, under the threat of legal action from Holt, there would be no second edition for 72 years. In the two copies now held by the college’s Department of Archives and Special Collections, Holt’s handwritten comments reveal the extent to which Rice’s words had stung: “Untrue,” “lies,” “never happened,” “doubt that occurred” and similar sentiments can be found scribbled in the margins.

It’s clearly true that Rice—like most dyed-in-the-wool Southerners—was a raconteur willing to sacrifice academic rigor for the sake of a more compelling narrative. It’s equally true that Rice felt deeply wronged by Rollins—as he did about everywhere he worked—and wished to present the college in the worst light possible. So, while the overarching events he described are verifiably true, certain snarky details must be taken with a proverbial grain of salt.

I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century was reissued in 2014 by the University of South Carolina Press through its Southern Classics series. In an afterword to the most recent version, Rice’s late grandson, William Craig Rice—then director of education programs at the National Endowment for the Humanities—was adamant that the manuscript, while biting in places, contained no libel.

“The suppression of his first book, five years in the making, became a grievous loss for John Andrew Rice, especially after the disappointment of Black Mountain,” wrote his accomplished grandson. “It also deprived general readers of an American autobiography of a distinctive voice during a period of literary and cultural ferment in the South.”

Indeed, Rice’s views on race relations in the South are among the most interesting passages in I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century. His unvarnished observations can seem a bit jarring to modern readers, but he remained steadfast that “white trashery” was the biggest social problem in the region—and placed his criticisms of African Americans, who were often only one or two generations removed from slavery, within the context of an oppressive system fostered by whites.

As for Rice, he divorced his first wife and, in 1942, married Dikka Moen, with whom he had two more children. He then began a new career as a writer of fiction, contributing pieces to such publications as Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, Harper’s and the New Yorker.

Rice also published a book of short stories, most of them about the day-to-day lives of African Americans, entitled Local Color (Dell, 1955). The book, now out of print, boasts a foreword by novelist Erskine Caldwell (God’s Little Acre, Tobacco Road), who writes: “This is the South I know, stripped bare of its magnolias and manners.”

The stories in Local Color bear some resemblance to those of Zora Neal Hurston—whom Rice and a handful of other professors had befriended during her visits to Rollins—in their use of vernacular language. The writing is richly expressive, but the persistent use of dialect by a white author—even a sympathetic white author who had heard such speech since childhood—can seem off-putting today.

Rice, who was never again offered a teaching position, found contentment in retirement and died in 1968 at his home in Maryland. Although his progressive views and values appear better suited to modern times, he never shook the notion that he was born a century too late and might have found more kindred spirits in an earlier era.

He told Time magazine that if he had his life to live over again, he would “choose the 18th century for its violence, yet touched with grace … for its long, clockless days … for its passionate belief that the world would be better, perhaps tomorrow … for its simple faith in simple words: justice, freedom, happiness; and belief in the rights of man, and faith in man.”

‘I’M SO (NOT) SORRY’

Among the papers related to John A. Rice in the Rollins College Department of Archives & Special Collections is a typewritten apology that seems to have gone undelivered.

It’s labeled “A Suggestion for a Letter from Professor Rice to President Holt,” but scrawled across the top of the page are the words “Copy of Bailey Letter.”

Bailey is Thomas Pearce Bailey, a professor of ethology and psychology, who composed what he hoped would be a job-saving missive for Rice to send to President Hamilton Holt.

Although Bailey pushes all of Holt’s hot buttons about “loyalty,” “incivility” and the “moral value of conformity,” it’s highly unlikely that Rice agreed to use the letter. But the tone would surely have pleased Holt—had it been sincere and actually written by Rice.

––––––

When a man has been judged by his friends to have acted in a manner that is unseemly, a manner that has given the impression of hatred and disloyalty, he is in duty to himself and others bound to change his attitude and conduct so as to conform to the standards held by good citizens, spiritual sportsmen, gentlemen and practical idealists.

I am such a man, and the consequences of my actions have caused me to recognize my derelictions and to make amends as I can. I have mistaken license for liberty and incivility for frankness. I have sometimes forgotten the moral values of conformity.

I have sometimes given strong meat to babes. For all these aberrations and more, I am deeply sorry. And I ask that my sincerity be judged by my actions in the future. I am ready to ask forgiveness of anyone whom I have offended.

I desire to be summarily removed from my office if at any time I seem seriously to have departed from my promise of amendment. And I request that you send a copy of this letter to all whom I have offended.