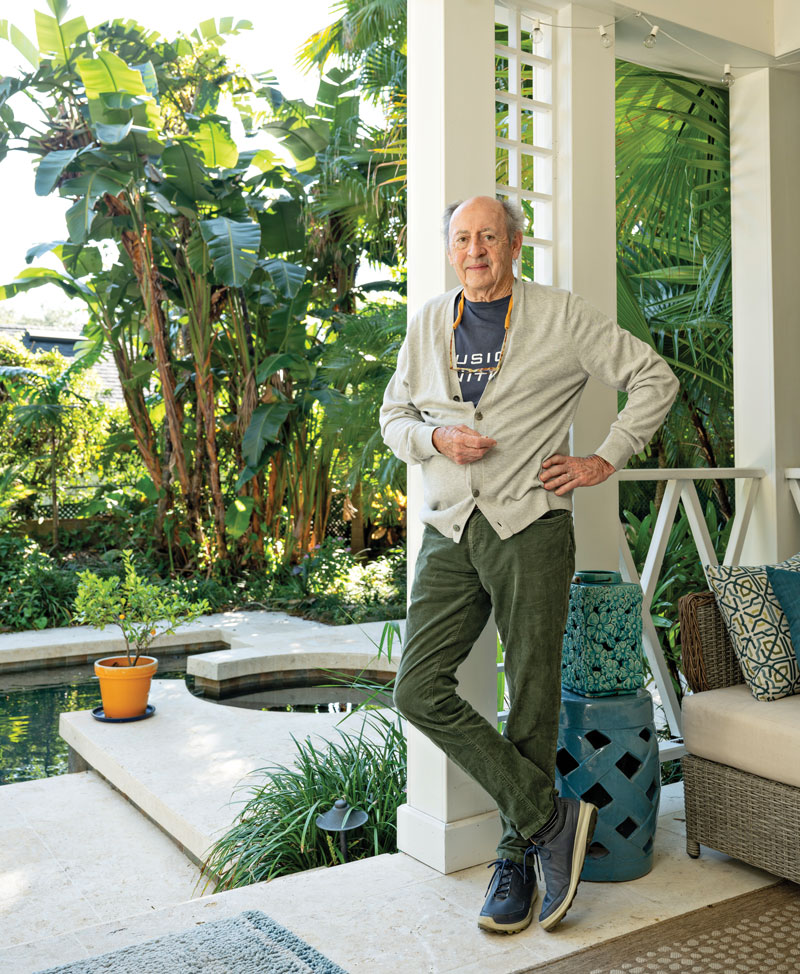

We tend to think of poets as laborers, unappreciated and suffering for their art. That’s hardly the case with Billy Collins, twice a U.S. poet laureate (2001 and 2003) who has been dubbed “the most popular poet in America” by The New York Times and happens to be a resident of Winter Park.

At age 83 (chronologically, at least), Collins has been adopted by locals as their favorite resident celebrity and the most important writer to have his royalty checks mailed to what’s now the 32789 zip code since novelist Irving Bacheller (Eben Holden: A Tale of the North Country) lived in the Isle of Sicily neighborhood before World War II.

Collins’s books have been bestsellers, his TED Talks have been viewed by millions of people across social media platforms and his in-person readings have been sold-out lovefests. In fact, Collins may be the only poet ever to have toured with an alt-rock star (Aimee Mann) and opened for a jazz icon (Dave Brubeck).

Just as Lynyrd Skynyrd’s audiences often shouted for “Freebird,” Collins’s fans have been known to call (more politely, perhaps) for the poet’s own greatest hits, such as “The Lanyard,” “The Death of the Hat,” “The Revenant,” “Questions About Angels” and “Another Reason Why I Don’t Keep a Gun in the House.”

Robert Frost, who, like Collins, enjoyed enormous popularity during his lifetime, once said: “There is a kind of success called ‘of esteem,’ and it butters no parsnips.” Collins, although he surely appreciates being “of esteem,” very much prefers his parsnips buttered.

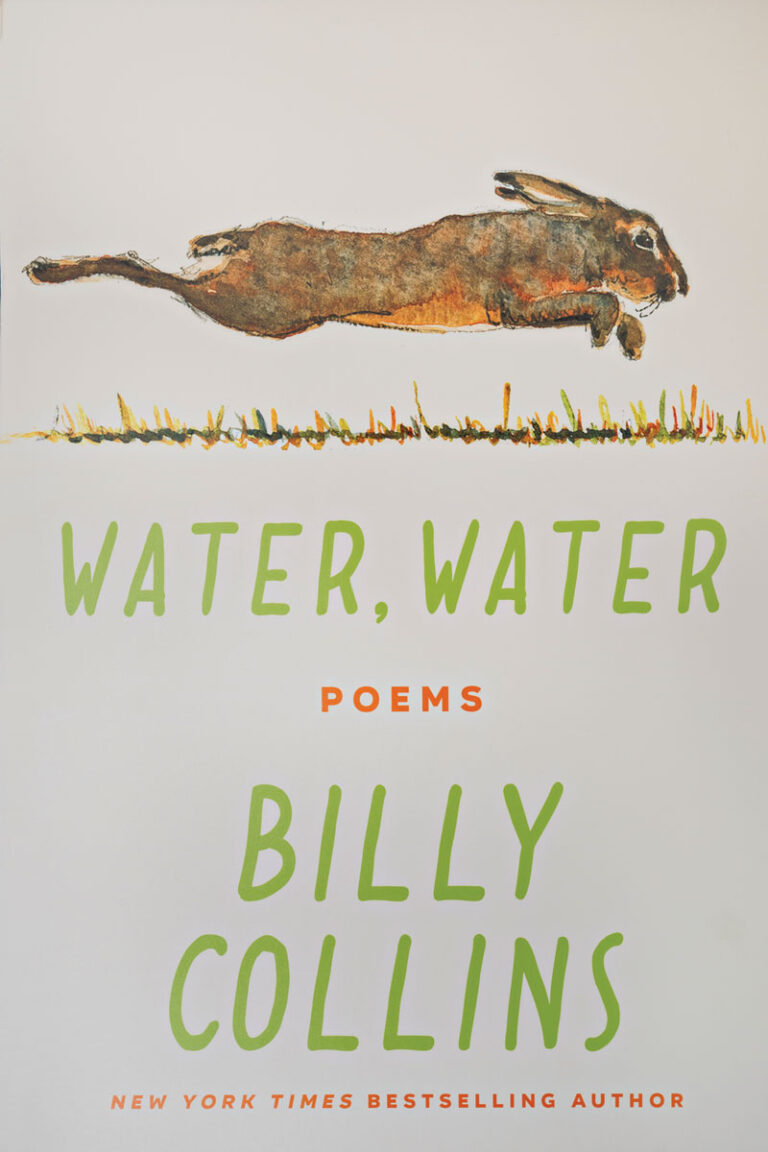

So, break out another tub of Land o’ Lakes! Water, Water (Penguin Random House, 2024), Collins’s most recent collection, will make a splash—and quench the thirst—of countless faithful readers who’ll know just what to expect when they crack open their copies: Poems that are, as John Updike has described them, “limpid, gently startling, more serious than they seem.”

Water, Water, as a title, is a nod to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, in which a sailor whose ship is stuck in an ice floe laments that there is “water, water, everywhere / Nor any drop to drink.”

In the book, Collins includes a poem of the same name that features not an ancient mariner but the author himself (who is the central character in most of his poetry) standing chin-deep in lake water—“where I do some of my best thinking”—and feeling thoroughly overwhelmed with happiness until a “doomsayer thought” invades his reverie. Writes Collins:

“This kind of thing can go on some time, / thoughts running around my head / like a stampede of antelopes / only sometimes, one of the young stumbles, / and is set upon by a pack of cheetahs.”

Collins’s previous collection, Musical Tables, included 125 playful and sometimes-profound “small poems” of no more than a few lines each. This minimalist masterpiece, released in 2022, marked a departure in form, but not one so drastic that the voice, even when distilled, wasn’t instantly recognizable.

In Water, Water, Collins—whom one critic has credited with “putting the fun back into profundity”—offers 60 works of various lengths that explore such subjects as birds, dogs, horses, love, loss, pineapples, jazz, the alphabet, the universe, the afterlife and Elsie the Cow—just for starters.

The collection opens with a lovely contemplation, “Winter Trivia” (see page 96), that is vintage Collins and demonstrates why he is a poet and most of us are not. The poem considers the homey interactions that occur between friends during the two hours required for a snowflake to fall from a cloud to the earth. Who else but a poet would even imagine such a premise?

In “While in Amsterdam,” Collins, an avid fan of jazz, visits the site of trumpeter Chet Baker’s mysterious death, which leads (circuitously) to a hilarious digression about the discordance of violins in jazz bands: “It always sounded like a violinist / had wandered into the wrong / recording studio and just / started playing along with the others / only slower and not as well.”

In “Being Sonny Rollins,” Collins confronts, and ultimately comes to peace with, the “blunt fact” that he is not, and never will be, the revered saxophonist. “I watch hundreds of scattered black birds / wheeling and squawking in the sky / but that cowbell intro to ‘I’m an Old Cowhand’ / reminds me that I am someone other than Sonny Rollins.”

Speaking of old cowhands, in “Poem Interrupted by Gabby Hayes,” the poet’s random musings about his hazy past are inexplicably and parenthetically crashed by out-of-the-blue exclamations from Gabby Hayes, the cantankerous screen sidekick of Roy Rogers. (“Well, I’ll be a possum’s grandpa!”)

Collins’s parents make cameos in Water, Water, nowhere more poignantly than in “The Thing,” in which he ponders a porcelain bowl “with its hand-painted pictures / of flowers and small birds.” The bowl is, even if only to him, much more than an inanimate object because it had belonged to his mother.

Less sentimental and more provocative is “Sunday Drive,” in which Collins happens upon a collection of congregants filing into a clapboard church. He resists an urge to stop and announce that neither believers nor non-believers will be disappointed (or smug) when they die “for the simple reason / that they will be dead at that point / and incapable of experiencing anything.”

Other selections good-naturedly lampoon melodramatic poetry (“Addressing the Heart”), ponder the preservation of literary legacies (“Display Case”), lament ugly romantic breakups (“Deep Time”), reminisce about the vicissitudes of teaching undergraduates (“Lesson Plan”) and celebrate the lack of ornamentation in modern typography (“Incipit”).

And yes, Winter Park—where Collins, a native New Yorker, has lived since 2008—makes an uncredited appearance via “The Peacock,” which describes the feathered exhibitionist crossing a suburban street “until the long concluding plumage, / with no reason to display its iridescent / fan of eyes, was dragged over the far curb, / following, as always, the resolute body of the bird.”

You get the idea. But can poetry that’s enjoyed by the masses (people like us), poetry that eschews traditional structures, poetry that’s often funny, truly be considered serious literature? Collins, who appreciates classical forms (even though he doesn’t use them) as much as any orthodox academician, doesn’t worry about such matters.

“If you break away from the pack and attract a broader audience, sometimes you’re derided by the very people who complain about a lack of readers for poetry,” he noted at a local reading several years ago.

Continued Collins: “If being accessible means it’s easier to get into the poem, then I’d compare that to an accessible building. It’s easier to get into—but once you’re inside, all sorts of interesting things can happen.”

A more apt description of Water, Water is difficult to imagine. But the same could be said of any collection by Collins, an eternally hospitable host for the genre in which he writes. All you have to do is open the book and wander around.

During your exploration, you’re guaranteed to experience some combination of goosebumps, misty eyes, ragged sighs and aha moments galore. Such reactions are amplified when you hear Collins read his own work—his often-droll delivery is masterful—so hopefully he’ll schedule a local event to do so.

In the meantime, we’re celebrating the release of Water, Water—Collins’s 13th collection—by asking “Professor Bebop” (as some fans have dubbed him) a breezy 10 questions about everything from his writing style to the impact on his poetry of becoming a Floridian (“What in tarnation?”). Sorry—we’ll try to keep Gabby Hayes from interrupting again.

What led to your becoming U.S. poet laureate?

The appointment of the U.S. poet laureate is something of a mystery. The Librarian of Congress makes the appointment. It’s perhaps the only purely autocratic decision made within the Beltway. Absolutely nothing to do with the White House. No application, no short list, no consensus—the phone rings and you’re it! My poetry output suffered drastically. I was moved from the solitude of composition into the spotlight of the public eye. I thought I might be the first Christian martyr to be interviewed to death.

You’ve been described as a poet for people who think they don’t like poetry. Earlier in your career, did you use a more formal and traditional style? If so, what influenced development of the distinctive, conversational voice in your work that attracts such a broad audience?

The only way to develop a distinctive voice in poetry (or playing the saxophone) is through imitation. I did not begin as a formalist, if by that we mean end-rhyme and set meter. I began imitating the Beats, who brought a new looseness to poetry. The major change in my poetry was from dead seriousness to a mix of the serious and the comic.

Some readers noticed what they thought was an unusual number of poems about mortality in your previous collection, Musical Tables. Was that on purpose?

All my books are about what I call “the thrill of mortality.” Carpe diem is the oldest theme in poetry. Readers are asked to seize their diems because only a limited number of them remain. The poet taps you on the shoulder with a cold finger. Some people need a near-fatal accident to remind them that life is precious. Readers of poetry don’t require such abrupt disruptions.

While you were poet laureate, you wrote a very moving poem called “The Names” that you read before a joint session of Congress on the first anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. How did you decide on the correct approach to writing about such a weighty (and still-fresh) tragedy?

It was a challenge that I overcame by making two formal decisions. I chose the elegy—a poem for the dead—as my genre, and I used the alphabet as guideposts to lead me through the poem. Only under those confines did I feel free to write the poem.

You were very vocal in your stance that Bob Dylan deserved his 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature. Do you have a similarly expansive view of what poetry is or is not? Are there forms and conventions that any work called a “poem” needs to display?

So many different kinds of written expression fall under the umbrella heading of “poetry,” it would be foolish to judge which ones are worthy of the title. But I think the line is crucial. Poetry comes in lines like gas comes in gallons. Once the poetic line is forsaken, as it is in the “prose-poem,” it might be time to find another name for what you’re doing.

Your poems—especially your short poems—are so finely wrought, with meaning behind every word and a wallop the end. I’ve got to think that the process can’t be as effortless as you make it seem, although I’m sure some come more easily than others. Can you make any generalizations about how easy (or how hard) writing a Billy Collins poem is?

One has to labor in order to sound spontaneous. Yeats put it this way: “A line may take us hours maybe; / But if does not seem a moment’s thought / Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.”

Any “Billy Collins’s Greatest Hits” collection would include “The Lanyard,” I imagine, and others that have been widely anthologized, such as “The Revenant,” “Introduction to Poetry” and “Another Reason Why I Don’t Keep a Gun in the House.” But do you have some personal favorites?

I sometimes hear from readers that they have favorites. I have no favorites because I have no interest in poems I’ve already written, only in what poem may come next, or the poem I’m in the act of composing. Once the poem is completed, it’s out of my hands. My door closes and the reader’s opens.

Many people who create art for public consumption say they do so with a type of person (or even a specific person) in mind who represents the audience. When you write, do you ever consider who your readers are, or do you write what pleases you and figure that it will resonate?

I think of my audience as a single person, no one in particular, but someone like me, who enjoys being alone and who reads poetry to feel even more alone. A stranger who will fall in love with me and whom I will never meet.

You’re a native New Yorker. Has working in Florida impacted your work in any way? Most of your poems are universal, but in your last few books I’ve noticed that more are set in the Sunshine State.

I typically locate my speakers in a specific natural environment. When I lived in Westchester County, there were deciduous trees, stone walls, gravel driveways and hydrangeas. Now, it’s palm trees, heavy rain, egrets, and tall, priestly herons. If I lived in Iceland, it would be ice. As they say, everyone has to be somewhere.

Your collections of poetry are very eclectic, from poignant to hilarious, and on subjects that run the gamut. How do you decide what to include in a book? Have you ever considered compiling a book in which the poems all relate thematically?

Like ball players who always say they’re going to take it one game at a time—as if there were another way—I write one poem at a time. I don’t consider a poem as part of a future book until I have about 60 good ones and it’s time to rake them into a pile and see if they add up to a book. My editor will help with that decision. I never think about the “theme.” That’s a question for the classroom. If I noticed that a poem I’m composing was developing a theme, I’d immediately turn it in some other direction.

BILLY COLLINS: A LIFE THUS FAR

Every morning, Billy Collins sits in the same chair—sometimes with an encyclopedia for inspiration—and reads poems “to get in the proper state of mind; something usually results.”

Collins writes only in Fabio Ricci notebooks and uses only Palomino Blackwing pencils—preferably the pearl edition. His lined notebook pages are filled with poems in various stages of completion, the scribbled words adorned with arrows and strikethroughs.

A native New Yorker, Collins was born in Manhattan and raised in Queens and White Plains. His father, William (Bill), worked for an insurance agency, while his mother, Katherine (Kay), was a nurse who quit her job to raise the couple’s only child.

Bill—a dapper extrovert who called his only son “Champ”—brought home editions of Poetry magazine, which made an impression on the writerly youngster, who recalls penning his first poem at the age of 10, about a sailboat he saw tacking up the East River.

After graduating from Archbishop Stepinac High School in White Plains, Collins attended the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, earning a B.A. in English. He then enrolled at the University of California, Riverside, earning an M.A. in English and a Ph.D. in Romantic poetry.

His first classroom post was as a teaching assistant at San Bernadino Community College. Then it was back to New York and Lehman College, part of the City University of New York (CUNY), where he taught English and composition. (Although he had stopped teaching years before, Collins remained affiliated with CUNY for a half-century, retiring in 2017 as a distinguished professor.)

Academia provided a steady paycheck, but Collins, from the time he was in high school, always thought of himself as first and foremost a poet. He assigned his students the task of memorizing a poem of their choosing, hoping that the work would remain with them for life.

Collins’s first book of poetry, The Apple That Astonished Paris, was published in 1988. The collection included some of his most anthologized poems, including “Introduction to Poetry,” “Another Reason Why I Don’t Keep a Gun in the House” and “Advice to Writers.”

He also published poems in The Atlantic, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Poetry Magazine and Rolling Stone, refining along the way a witty and at times sentimental poetic persona that Collins refers to as his “writing self.” That self, Collins notes, is “monastic, detached, doesn’t have a job—he drinks tea, I drink coffee.”

Collins the writer has thus far published 13 books of poetry, while Collins the personality has appeared regularly on A Prairie Home Companion—the first time in 1998, after which his book sales skyrocketed—and on other NPR programs, including Fresh Air with Terry Gross. The TED Talk in which he recites two poems about the inner thoughts of dogs has garnered nearly 1.6 million views.

Collins was still teaching at Lehman College in 2001 when he was asked by Librarian of Congress James Billington to serve as the country’s poet laureate. In that post he launched “Poetry 180,” for which he selected 180 poems (one for each day of the school year) to be read aloud to students, but not analyzed, at high schools across the country.

But following September 11, 2001, the largely honorary post gained unanticipated gravity. As the first anniversary of the terrorist attacks approached, Collins was asked to compose a poem commemorating the victims—and to read it before a joint session of Congress held in New York City. The now-iconic concluding line still resonates: “So many names, there is barely room on the walls of the heart”.

(Collins, not wishing to appear exploitative, initially chose not to include “The Names” in any of his books. It first appeared in The Poets Laureate Anthology, released by the Library of Congress in 2010. It was finally published in Aimless Love, the poet’s 2013 collection.)

Winter Park wasn’t on Collins’s radar until 2002, when he conducted a reading at Valencia College and met attorney Suzannah Gilman, a poet herself, who had previously written him a fan letter (well, an email).

In the book-signing line, when Gilman’s turn came, she reminded Collins about the correspondence. Then, much to her amazement, the visiting VIP pulled a printed copy of the email out of his jacket pocket.

At the time, Collins and Gilman were near the end of troubled first marriages. They struck up a friendship that became a romance—at first, a long-distance one—until Collins moved to Winter Park in 2008. (The couple married in 2019.)

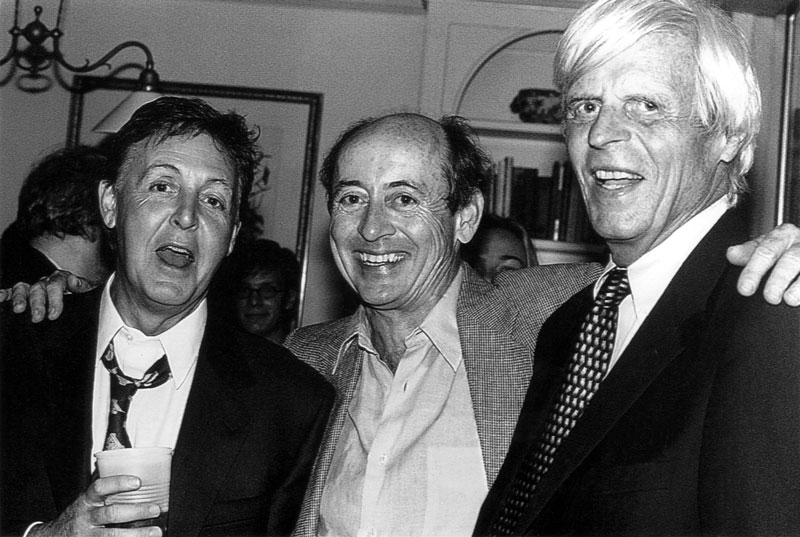

Soon after relocating, Collins accepted the position of senior distinguished fellow at the Winter Park Institute, then affiliated with Rollins College. His celebrity status attracted such big-name guest speakers as Sir Paul McCartney, Paul Simon, Garrison Keillor, Jules Feiffer and Jane Pauley.

The Winter Park Institute was discontinued in 2016, when President Lewis Duncan resigned, but was reinstated by incoming President Grant Cornwell, who in 2020 pulled the plug yet again, citing the financial hit expected from COVID-19. (The Institute exists today as a nonprofit separate from the college, and with no involvement by Collins.)

For decades an international figure, Collins certainly never needed an imprimatur from Rollins. Still, the pandemic also abruptly scuttled travel and personal appearances, prompting Suzannah to suggest launching The Poetry Broadcast over Facebook. Her husband, a warm and witty media-savvy personality, agreed to give it a try.

The format was similar to that of a late-night talk show, sans guests. Six days a week at 5:30 p.m., Collins would appear at a desk in the office of his home with a sheaf of papers and a pile of poetry books to conduct live-streamed readings (of his own poetry and that of others) and discussions for a global audience.

The Poetry Broadcast quickly took on a life of its own. During each 30-minute installment, thousands would log on and, in real time, post hundreds of comments and questions that Suzannah would monitor and often pass along. Collins continued the project, originally intended as a brief lockdown diversion, for 52 months, until August 2024.

Over the past several years, Collins has released more books, resumed his schedule of personal appearances and, with a nod toward his legacy, has placed his notes, diaries and other historical papers at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas in Austin.

His Fabio Ricci notebooks (among other things) will be in good company among the archives of such fellow literary luminaries as T.S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, Ezra Pound, E.E. Cummings, Anne Sexton and Dylan Thomas.

Collins has also donated $250,000 to create an endowed scholarship in classics at his alma mater, the College of the Holy Cross. He credits what he learned at Holy Cross about both the humanistic philosophies and rhythms of language invented by the ancients as bedrock to his success.

Not surprisingly, prestigious organizations are always bestowing upon Collins awards of one kind or another. Accolades include the Mark Twain Prize for Humor in Poetry (he was the inaugural recipient) as well as fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. In 1992, he was chosen by the New York Public Library to serve as “Literary Lion.”

In 2017, Collins was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters, an honor society of the country’s 250 leading architects, painters, composers and writers.

—Michael McLeod and Randy Noles