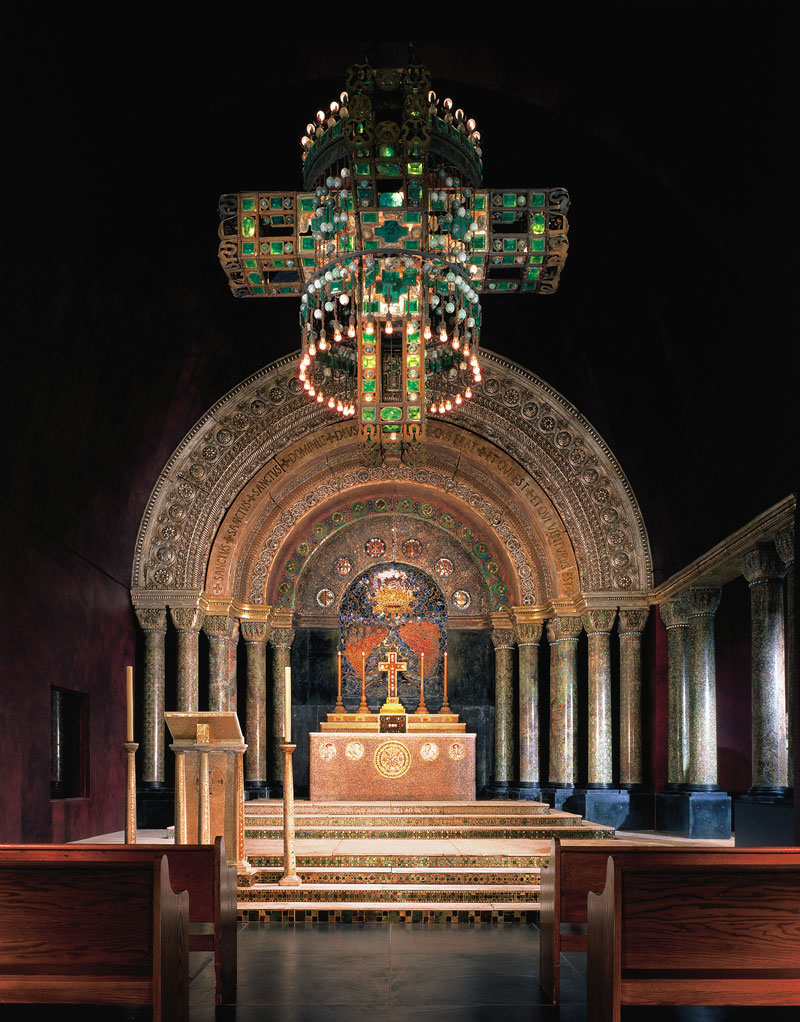

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago—also known as the Chicago World’s Fair—saw the debut of the Ferris wheel. Less over-the-top (but not by much) was a small jewel-box of a Byzantine-inspired chapel interior designed by an artist named Louis Comfort Tiffany.

The elaborate 800-square-foot showpiece was seen by an estimated 1.4 million people at the fair’s Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building, and established Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, 333 North 4th Avenue in Lower Manhattan, as the country’s premier studio specializing in art glass and architectural décor.

After the fair, however, the chapel all but disappeared from view for more than 100 years only to be rescued, reassembled and restored for the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, where it has dazzled visitors since 1999.

What a long, strange trip it has been.

“Like a cat, this chapel seems to have had nine lives,” says Morse Museum Director Jennifer Thalheimer, who will oversee a celebration of the born-again chapel’s 25th anniversary in Winter Park. Like a theatrical set piece, she notes, it was fashioned from inexpensive materials and never meant to last much beyond its stint in Chicago.

And yet, here it stands, as awe-inspiring as ever. To mark the chapel’s silver jubilee locally, the Morse Museum has mounted a new exhibition, After the Fair, which will trace the hair-raising journey of the eye-popping exhibition from the Windy City to the City of Culture and Heritage. Members may attend a reception on Monday, October 14, to celebrate the opening of After the Fair, which will likely remain on view throughout 2025.

Also on display will be a monumental mosaic, Fathers of the Church, as well as other surviving elements of the fair that opened 131 years ago. The mosaic was the first to come out of Tiffany Studio’s newly formed Women’s Glass-Cutting Department.

Fathers of the Church—crafted by a cadre of self-styled “Tiffany Girls”—will be on loan from The Neustadt Collection, a nonprofit decorative-arts archive based in New York that owns hundreds of Tiffany lamps and windows and the world’s largest trove of glass creations from Tiffany Studios.

In addition, the Morse Museum will bring back a Tiffany window, View of Oyster Bay, that it had loaned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City for display in its American Wing. The wing will undergo renovations next year, so this was an opportune time to return it to Central Florida.

Tiffany—who enjoyed a surge in both ecclesiastical and residential commissions as a result of the chapel display—designed the 5-by-6-foot window for a Manhattan townhome owned by industrialist William C. Skinner. Scholars say the artist likely borrowed a similar view from his own studio and added purple wisteria to this art-glass masterpiece of blues, lavenders and greens.

The events leading up to the Silver Anniversary celebration are truly cinema worthy—packed with unlikely characters, artistic intrigue, serious sleuthing and even a romantic relationship between two heroic visionaries whose shared objective was to rehabilitate the reputation of a now-iconic artist whose output had fallen out of vogue.

Here, then, is the well-traveled chapel’s whirlwind of a backstory encased in a hued-glass, faux-jewel-encrusted nutshell. As Robert Ripley would have said, you can believe it or not.

THE DIAMOND QUEEN

When the yearlong World’s Columbian Exposition ended, the opulent installation was disassembled and returned to Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company, where it was reassembled and put on display. It was purchased the following year for $50,000 by Chicago resident Celia Whipple Wallace—a wealthy widow with expensive taste in jewelry who was dubbed the “Diamond Queen” by the press.

Wallace, in turn, donated the chapel to the still-under-construction Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in New York City’s Morningside Heights neighborhood. Because negotiations regarding the gift’s particulars became protracted, the chapel wasn’t moved until July 1898, when it was again taken apart, packed into 81 crates and turned over to the Episcopalians.

However, because the church project was catastrophically over budget and behind schedule, Tiffany’s shimmering sanctuary—which Wallace believed would eventually be incorporated into a grand main worship space—was pieced together in a subbasement and used for smaller services until April 1911.

By then, Ralph Adams Cram—a proponent of austere gothic architecture—had been hired to complete St. John the Divine. Cram (who, coincidentally, later designed Knowles Memorial Chapel at Rollins College) wanted nothing to do with the gilded-age excess associated with Tiffany, whose style was the antithesis of his own.

Consequently, the now-unused chapel remained in the dank crypt and fell into disrepair before Tiffany himself reclaimed it in 1916, making some changes and additions and installing it in an outbuilding at Laurelton Hall, his estate in Oyster Bay on Long Island.

What did the Diamond Queen, the original donor of the chapel, think about all these goings on? The answer isn’t known, but Celia Whipple Wallace appears to have been dealing with more pressing matters of a personal nature. Having blown through her fortune, she died in 1916, at age 83, alone and broke in Savin Rock, Connecticut.

Wallace’s troubles—which remain cloaked in mystery—were of long standing and may have been related to legal battles with the family of her late husband, wealthy timber magnate John S. Wallace, during which her mental state was called into question.

A bizarre story from the Chicago Tribune in 1902 reported that Wallace had abandoned her room at the plush Auditorium Hotel—where she lived in “near-regal fashion’’—owing $444 in rent and leaving behind dozens of dresses and opera cloaks, 35 hats, nine boxes of shoes, an oil painting and such “bric-a-brac” as a guitar and a dagger from Japan.

“Why, I haven’t enough [money] today to buy a music box,” the erstwhile socialite matter-of-factly told reporters after she was located by friends 14 years later. If she explained why she had vanished and where her money had gone, it wasn’t reported in contemporaneous newspaper accounts.

The chapel remained at Laurelton Hall until Tiffany’s death in 1933, when the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation assumed management of the estate. By 1946, however, the foundation was in financial trouble and began to sell off property and the contents of the home. Elements of the chapel were donated to regional religious and educational organizations.

In 1957, a disastrous fire heavily damaged Laurelton Hall but spared the chapel outbuilding. By then, however, Tiffany’s work had been so maligned by the art world’s cognoscenti that it was considered virtually worthless. What was left of the once-imposing mansion—and the treasures it still contained—was set to be razed.

Hundreds of stained-glass windows (including View of Oyster Bay) and architectural elements would have been lost forever had Rollins College President Hugh F. McKean and his wife, artist and interior designer Jeannette Genius McKean, not intervened. To the McKeans—especially Hugh—it was a personal matter.

HUGH AND JEANNETTE

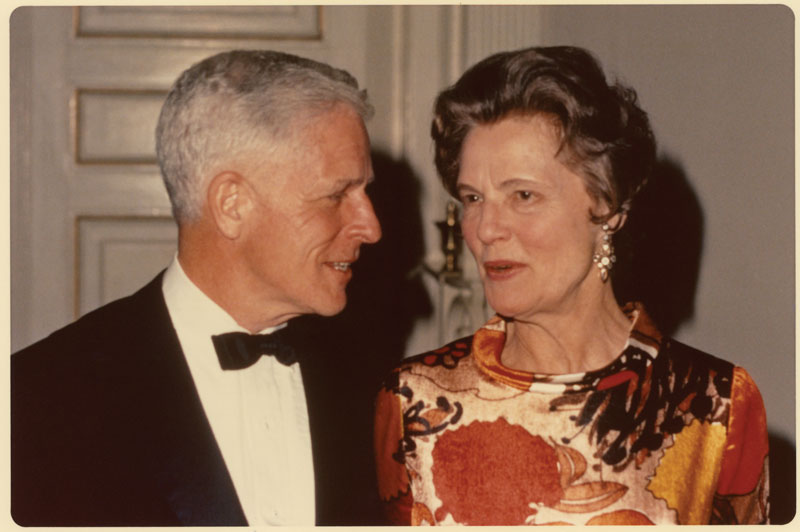

Those who spent any time with Hugh McKean likely remember him as a dashingly patrician older man with a shock of wavy white hair, a twinkle in his eye and a square jaw indicative of the matinee-idol good looks that he enjoyed in his youth.

They recall McKean’s wry humor, his courtly manner and his cultural pursuits, usually aimed at making art more accessible to people not generally inclined to visit museums. His endearing quirks, too, are well remembered—although he disliked being thought of as quirky.

In 1967, for example, McKean submitted to the Rollins board of trustees an annual report that was hand-lettered and illustrated with whimsical cartoons. And in his post-presidential years, he began salvaging and restoring signs—particularly garish neon ones—from defunct local businesses, including two from notorious strip clubs in Seminole County.

Others who didn’t know McKean personally still know of him through his vocations and avocations: educator, painter, philosopher, philanthropist, preservationist, college president and founding director of the Morse Museum, where the eclectic collection includes one of the world’s most impressive assortments of works by Louis Comfort Tiffany.

It was also Hugh and Jeannette who brought the first peacocks to Winter Park and opened the grounds surrounding their Spanish revival-style villa, Wind Song, to let the public see the noisy peafowl strut and preen. Today, a peacock is emblazoned on the city’s official logo.

Undoubtedly, McKean came to embody Winter Park in all its sophisticated yet egalitarian panache. But had he not become engulfed by the responsibilities of being Hugh McKean, community patriarch and cultural ambassador, he might have become as well known for his paintings as for his projects

For as long as he lived—and despite constant demands for his time and attention—McKean continued to create. Ensconced in an apartment above the Winter Park Land Co. overlooking Park Avenue, which he dubbed his “scriptorium,” he surrounded himself with canvases, brushes and tubes of oils.

He delighted in producing pictures that reflected his particular and sometimes puzzling vision of humanity in general, and Florida in particular. No mere dabbler, he produced strikingly realistic family portraits as well as haunting, impressionistic images that contained supernatural elements, such as ghosts and angels, often found in folk art.

Even the name he gave his sanctuary was vintage McKean: A scriptorium, literally “a place for writing,” is commonly used to refer to rooms in medieval European monasteries devoted to the copying and illustrating of manuscripts by monastic scribes.

McKean was a high-profile public figure, not a sequestered monk. So perhaps the moniker was nothing more than a reflection of his sometimes-ironic sense of humor. Or perhaps it was meant—in an unpretentious way, of course—to signal his belief that the work he produced while cloistered there had significance.

Born in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, in 1908, McKean was the second-eldest son of parents Arthur, an attorney who served for a brief time in the Pennsylvania legislature, and Eleanor (neé Ferguson), a homemaker. He had three brothers: John (1907–1993), Keith (1915–2007) and Vance (1917–2019).

Not surprisingly, Arthur was a man of many interests. In addition to careers in politics and the law, he roamed the sidelines for five seasons as head football coach at his alma mater, Geneva College, from which Eleanor had also graduated. While they weren’t wealthy, the McKeans were well-connected, socially prominent and solidly upper middle class.

In 1920 the family moved to Orlando, where they lived in an impressive home, since demolished, on Hillcrest Street near East Colonial Drive. According to U.S. Census records, the home was then valued at $40,000—the equivalent of more than $600,000 today. Arthur practiced law, became a municipal judge and ran unsuccessfully for mayor, as a Democrat, in 1930.

McKean graduated from Orlando High School in 1926 before enrolling at Rollins, where he majored in English and creative writing. His father had insisted that he earn an undergraduate degree in a subject other than art. That same year, he met a young woman who would become the love of his life—17-year-old Jeannette Morse Genius, a Chicago resident who had vacationed in Winter Park since childhood and was now taking summer classes at Rollins.

Jeannette’s maternal grandfather was Charles Hosmer Morse (1833–1921), the Windy City industrialist who shaped modern Winter Park and is remembered today as the city’s most important benefactor. A serious artist, Jeannette—who would become a Rollins trustee at age 27—had attended exclusive private schools and, like her future husband, would later study in New York at the Grand Central School of Art and the Art Students League.

This pair of kindred spirits—who would individually and separately dedicate their talent and treasure to energizing Winter Park’s cultural life—struck up a romance that blossomed like an iconic Tiffany daffodil.

“I learned to appreciate Tiffany through Hugh,” said Jeannette in a 1979 interview with the Orlando Sentinel. “He was an emotional and mental giant. I share his belief in the goodness of life. Hugh and I love nature, and that is the bond between Tiffany and us.”

SUMMER AT TIFFANY’S

McKean, though he didn’t major in art, spent the summer following his sophomore year in France, studying at L’École de Beaux-Arts in Fontainebleau. And while still a senior, he was named assistant instructor in landscape painting in the art department at Rollins.

He graduated in 1930, having followed his father’s wishes—at least nominally—by earning an academic degree. Arthur, perhaps resigned to having an artist in the family, then submitted two of his son’s paintings to the jury of the Tiffany Foundation.

One of those paintings, Ruins of Old Florida Mission, New Smyrna, earned McKean a Tiffany Fellowship, which allowed him to spend two heady months at Laurelton Hall, where Tiffany, age 82 and in failing health, hosted a sort of surreal summer camp for aspiring artists.

It was certainly inspirational to McKean, who later described the 84-room home and the 580 acres surrounding it as “a three-dimensional work of art, fabricated of marble, wood, plaster, winds, glass, copper, rains, light, sound, sunlight, flower gardens, running water, terraces, woods, hills.”

McKean also recalled the magnetism of Tiffany himself, frail but formidable, who spent evenings with his students offering kindly critiques of their work and “talking about the importance of beauty … I thought he was wonderful,” McKean later said of Tiffany, whose style even then was rapidly falling out of favor.

In the busy summer of 1930, McKean also studied at the Art Students League in New York, learning anatomy and figure drawing from George B. Bridgman, whose book Bridgman’s Complete Guide to Drawing from Life remains a classic in art instruction.

While in Manhattan, McKean somehow found the time for additional courses at the Grand Central School of Art, run by the Painters and Sculptors Gallery Association, a collective formed by painters Edmund Greacen, Walter Leighton Clark and John Singer Sargent. The following summer, he won a Carnegie Foundation scholarship to attend a series of art-appreciation lectures at Harvard University’s Fogg Museum.

Back at Rollins, McKean became a full-fledged art instructor. He returned to New York briefly in 1935 for a one-man show at Delphic Studios, a gallery established by a bohemian journalist, pacifist and patron of the arts named Alma Marie Sullivan Reed.

In 1937, McKean was named assistant to William H. Fox, chairman of the Rollins art department. Fox, previously director of the world-renowned Brooklyn Museum, undoubtedly shared with his young protégé a wealth of knowledge about collecting and exhibiting art.

Although McKean seemed to be leading a charmed life professionally, his family was in turmoil. After 1933, Arthur—who had invested in commercial real estate development and was devastated financially as a result of the Great Depression—no longer lived at the Hillcrest Street address, according to a city directory. By 1940, census reports showed his residence as New Kensington, Pennsylvania, where he operated a law practice.

In a turn of events no doubt facilitated by her son, 54-year-old Eleanor, who remained in Central Florida, went to work at Rollins. She spent three years—1935, 1936 and 1937—as what was then known as a housemother. Kappa Kappa Gamma, the sorority that employed her, would have supplied a salary and an apartment.

By 1938, Eleanor was no longer a Rollins employee. She was, for the time being, living with her son at 18 North Shine Avenue in a home valued at $7,500—the equivalent of about $125,000 today. (The two-story frame house, located near Thornton Park, last sold in 2015 for $400,000.)

In 1939, McKean enrolled in a one-year master’s program at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he earned a graduate degree in art history. Finally, with an art-related academic credential in hand,

McKean returned to Rollins, and shortly thereafter was elevated to art department chairman—a position he presumably would have happily occupied for the remainder of his career.

Although Arthur remained very much alive, Eleanor, who had by 1945 moved to an apartment on East Morse Boulevard, began referring to herself as a widow. No evidence can be found, however, that the couple ever divorced. In fact, Arthur’s 1957 death certificate lists Eleanor, who would die two years later, as his spouse.

Two of McKean’s former colleagues—both of whom considered themselves to have been close to him—say they’d never heard him mention a contentious situation involving his parents, even decades after Arthur and Eleanor were dead and buried (he in Beaver Falls, she in Winter Park).

Were they surprised by any of this? Not really. McKean, they agreed, was a private man who would have found it unseemly—worse yet, impolite— to dredge up family matters and discuss them with others. Besides, he was far more interested in looking ahead than in ruminating about years gone by.

COMING TO THE RESCUE

Jeannette, fatefully, decided in the late 1930s to fund construction of a facility on the Rollins campus that she would call the Morse Gallery of Art. It would honor the man who, in 1904, had bought much of Winter Park when its major landholders defaulted on a note.

But instead of maximizing the profit on his investment, Morse spent the rest of his life shaping what he considered to be an ideal small town—beautiful, well planned and brimming with cultural and recreational amenities. This project, thought Jeannette, would be an ideal tribute to her grandfather, who was low-key about his philanthropy.

Fortunately, she knew someone who would be perfect to run the gallery, which opened in 1942 on the site of the current Rollins Museum of Art. McKean, who shared his soulmate’s enthusiasm for collecting and sharing art with the community, got the director’s job—and kept it for the rest of his life.

Jeannette’s stature as both an artist and an heiress was undeniably a bonus for all involved since the gallery’s holdings quickly grew to encompass an intriguing assortment of fine art from America and Europe. Surely by now the couple was engaged, implicitly if not formally. But marriage would have to wait.

McKean, a lieutenant, junior grade, in the U.S. Navy Reserve, served three years in World War II, attaining the rank of lieutenant commander and spending at least a portion of his stint as an instructor at the Advanced Naval Intelligence School in New York.

The intelligence assignment was likely a result of his travel abroad; he and his friend John Tiedtke—later a philanthropist and primary patron of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park—had traipsed across Europe together in 1936, ostensibly to tour the continent’s great museums and concert halls. The navy’s intelligence units were actively seeking Americans who had spent time overseas.

Then, when McKean returned to Winter Park in 1945, he and Jeannette were finally wed. He was 37, she was 36, and their courtship—if such a prosaic descriptor is applicable—had spanned 18 years. The couple would have no children, but lavished attention on their hometown instead.

“Jeannette brought this huge fortune to the marriage, and Hugh brought all this knowledge,” recalled Keith McKean in a 1995 Orlando Sentinel obituary written about his brother. “So she learned more about art from him, and he and she together found ways to spend this fortune … They were wonderfully generous to the community.”

In 1951, McKean unexpectedly became president of Rollins following the brief, tumultuous tenure of a 33-year-old wunderkind named Paul Wagner, who had roiled the campus with massive faculty reductions and an autocratic management style.

The announcement of Wagner’s firing after less than two years and McKean’s subsequent elevation was greeted with outright glee. However, the beleaguered Wagner at first refused to vacate his office, forcing McKean to operate out of makeshift headquarters at the gallery.

When Wagner was finally deposed—and escorted from campus surrounded by police officers—McKean was carried around campus on the shoulders of celebrating students, many of whom had threatened to transfer or had gone on strike demanding the imperious president’s ouster.

(During the uproar, Jeannette, in her role as a trustee, at first recused herself from voting on her husband’s appointment. She relented only when other trustees convinced her that the vote should be unanimous.)

Although an art professor with limited administrative experience might have been an unconventional choice to run a college—particularly one so cash-strapped and steeped in intrigue—McKean went on to enjoy a successful 18-year presidency, which was followed by a stint as chancellor and chairman of the board of trustees.

McKean’s administration was not without controversy—he was never comfortable fundraising, for example, a chore he seemed to regard with particular distaste—but order was restored, budgets were balanced, courses of study were added and nine major buildings were constructed.

Enrollment soared (from 600 to 1,000) even as admission standards became more stringent. In addition, a business administration program that would become the Roy E. Crummer Graduate School of Business and an adult education program that would become the Hamilton Holt School were launched.

“A soft-spoken, artistic man with a penchant for philosophizing on any subject from the art of fishing to the meaning of art, McKean, with a gentle, unassuming manner, seemed an especially appropriate leader for the college in the post-Wagner years,” noted history professor Jack Lane in Rollins College Centennial History: A Story of Perseverance—which was written in 1985 but published in 2017.

McKean’s emphasis on instruction seemed to harken back to the days of President Hamilton Holt, who led the college to national prominence with his Conference Plan, which required extensive one-on-one interaction between students and faculty members.

As for the McKeans themselves, they had homes in New York, New Hampshire and California in addition to Wind Song, which had been built in 1936 on the shores of lakes Mizell, Barry and Virginia by Jeannette’s father, Richard Genius, who died in 1941. (Her mother, Elizabeth Morse Genius, had died in 1928.)

Hugh concentrated on the college, while Jeannette established herself as an interior designer and a businesswoman. (Her Center Street Gallery was a downtown fixture for nearly 40 years.) She also served as president of the Winter Park Land Co., founded by her grandfather, which still managed the family’s real estate holdings.

Both McKeans continued to paint, albeit in different styles. (Some of Jeannette’s works were abstract—a genre her husband never explored in his own art—while others depicted flowers and still-life arrangements.) They also involved themselves in countless civic activities, arguably becoming Winter Park’s preeminent power couple.

Then, in 1957, the already-diminished legacy of Louis Comfort Tiffany’s legacy suffered the ultimate indignity. Laurelton Hall burned and almost no one cared. Among the few who did care were the McKeans, who were among a handful of serious collectors who still revered Tiffany’s work. In 1955, they had defied convention by staging a Tiffany exhibition at the Morse Gallery comprised largely of pieces bought at bargain-basement prices from antique shops in Manhattan.

Although the proprietors were surely pleased to find anyone willing to buy their dusty art nouveau junk, they must have privately questioned the judgment of the apparently clueless Floridians who proved to be such eager customers. Tiffany? What could be more passé?

“Hugh once told me that if he just had some money, he could buy all this stuff Tiffany had done,” Keith McKean later recalled to the Orlando Sentinel. “He recognized its value immediately.” Now, because of his marriage, money was no longer an issue. And, because of the fire—a catastrophe, to be sure—he had an opportunity to become both a collector and a preservationist.

If, that is, there was anything left to preserve. Even as the ruins still smoldered, the McKeans (naturally) were asked by a Tiffany daughter, Comfort Gilder, to try and salvage what they believed to be important from the devastation. The couple hurried to Oyster Bay, where they were shocked and saddened at what they found.

“I shook something against a tree,” McKean wrote in his book The Lost Treasures of Louis Comfort Tiffany (Doubleday, 1980). “It rattled. The head of the wrecking company waiting to clear the property was with us. I asked him what it was. ‘That’s one of the old man’s windows,’ he replied.”

And not just any window. It was one of the Four Seasons windows, created in 1900 for the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Seeing this quartet of magnificent, fully restored panels today, it’s almost beyond comprehension that they were once regarded as little more than trash.

The McKeans, using a small fleet of rented moving vans, transported what would become the core of their collection—including the bulk of the chapel interior, pieces of which were stored in a maintenance shed near Wind Song. (The lush, 48-acre site where the McKean home still stands, frozen in time, is today owned by the Elizabeth Morse Genius Foundation.)

Among their chapel-related finds: Six plaster arches, 16 mosaic columns and, most showy of all, a cross-shaped, 15-foot-high electrified chandelier (called an “electrolier”) made from filagree, gilded pipe and “turtleback glass” (green glass blown to resemble a turtle’s shell). They paid $10,000 for the lot, and the estate was lucky to get it.

Over the next dozen years, the McKeans continued to track down such missing chapel pieces as candlesticks, leaded-glass windows, an alter and a lectern made of marble and glass and a dome-shaped baptismal font. But neither Jeannette, who died in 1989, nor Hugh, who died in 1995, would live to see the refurbished electrolier reunited with the resurrected chapel, where today it hangs in all its glory.

A MIRACULOUS RESURECTION

In 1977, the Morse Gallery of Art moved off-campus to a 6,000-square-foot repository on East Welbourne Avenue in downtown Winter Park. Two years later, it changed its name to the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art and became synonymous with Tiffany, who was by that time very much back in fashion.

But very little of the designer’s jewelry, pottery, paintings, art glass and leaded-glass lamps and windows could be displayed at any given time. Most of it was warehoused, along with hundreds of late 19th- and early 20th-century paintings, graphics and works of decorative art.

Then, in 1993, the city rejected McKean’s proposal to build a $29 million museum on the site of the Winter Park Golf Course, which undulated across 24.6 acres of land that had been inherited by Jeannette and was owned by the Elizabeth Morse Genius and Charles Hosmer Morse foundations.

Peevish in the face of pushback, McKean told city officials that the foundations “had no interest whatsoever” in building on the golf course “if it would cloud the century-long friendly relations between Winter Park and the Morse family.” If the city didn’t want a museum, he added ominously, he would “go someplace that does.”

Thankfully, a task force led by Mayor David Johnson identified a site on Park Avenue—the adjacent Fosgate and SunBank buildings—that could be transformed into a museum where the collection could be properly displayed. All parties agreed, and the foundations purchased the buildings in 1993 for $1.5 million. (The city bought the golf course for $8.1 million in 1996.)

McKean, by then suffering from cancer, remained intimately involved in every aspect of the project—designed by The Gantt Partnership, based in Orlando, and built by Walker & Company, based in Winter Park—but died just months prior to the new 16,000-square-foot facility’s grand opening. Near the end, he had refused his doctor’s offer of pain medication so that his focus on the task at hand could remain sharp.

“I never said that Jeannette and I had to live to see this,” an ailing McKean told the Orlando Sentinel as completion neared. The important thing, he added, was that the wonders within its walls could be shared with the community for generations to come. The story, then, might have ended with the ribbon-cutting ceremony that would perpetuate his generous vision.

But the chapel—elements of which still remained in storage—couldn’t be reassembled and displayed until considerable additional space was made available specifically for that purpose. Could this even be done? And, if theoretically possible, would such an audacious undertaking have met with the approval of Hugh and Jeannette? These questions were, of course, rhetorical.

In 1997, a $4 million, 4,300-square-foot expansion got underway to house the sumptuous but long-hidden sanctuary as it likely looked after being rebuilt at Laurelton Hall. That’s because there were only a handful of indistinct interior photographs that showed the display as visitors would have seen it at the Columbian Exposition, which meant replicating the original installation would have required too much guesswork.

While construction continued apace, groups of about a half-dozen artisans—supervised by Miami-based Rustin “Rusty” Levenson, a painting conservator who trained at Harvard University, and Pompano Beach-based John Maseman, an “object” conservator who trained at the Archeological Institute in London—got to work.

“There were so many aspects of this project that were amazing and not routine at all,” recalls Levenson, now retired, who was first told about the piecemeal chapel years earlier when she had met McKean. “I had seen it in crates—just shards of glass with no indication of how they came together. We solved it one step at a time. There were many unknowns, but we never reached a point when we thought it couldn’t be done.”

Levenson found those seemingly countless shards to be particularly enchanting. The tiny pieces of glass were layered, and each layer was painted to reflect light differently. The cumulative effect was to give mosaic-covered surfaces the illusion of movement. Adds Levenson: “How can you not be awed by that?”

Maseman—who died of cancer in 2012—restored the fragile plaster arches and columns and created duplicate forms when the scrollwork was seriously damaged. And teams of volunteers, including students, meticulously swabbed hundreds of thousands of semiprecious stones and postage-stamp-sized colored glass mosaic pieces that formed elaborate symbols and patterns, each holding a religious or spiritual meaning.

For example, in an entirely coincidental homage to Winter Park, a mosaic raredos showcases two peacocks facing one another beneath a radiant golden crown. In fact, because they molt every year and grow new feathers, even longer and fuller than before, peacocks often appear in early Christian art as a symbol of the resurrection and eternal life. Also, in Greek mythology, Hera, the queen of the gods, placed the eyes of Argus, her watchman, on the tail of a peacock.

Tiffany, as McKean once said of the chapel design, was “thinking in glass.” So, because there were no detailed plans to follow, Levenson and Maseman had, at times, been compelled to determine the artist’s intent by penetrating his psyche. Making matters more difficult, many stones had been jarred out of place during the apparently bumpier-than-expected journey from Oyster Bay to Winter Park.

Much of this under-the-radar undertaking—which combined months of tedium with moments of exhilaration—was carried out in the museum’s vacated prior location on Welbourne Avenue. Some project participants, including Maseman, became so immersed that they actually moved into the older building and slept on folding cots among the chapel’s broken remains.

Ultimately, in a marvel of arts, architecture and engineering, the conscientious cast of conservators overcame a cacophony of catastrophes and near-catastrophes—including damage to a priceless stained-glass window that warranted an urgent house call from restoration specialist Tom Venturella, who was flown in from New York. The installation was completed just in time for the scheduled grand opening in April 1999.

Was Tiffany’s ghost offering spiritual guidance from some opulent afterlife? Perhaps, but real-world credit for this feat goes in large part to the late Laurence Ruggiero, who was brought aboard as associate director of the Morse Museum in 1992 and took over as director upon the death of McKean.

Ruggiero, like many art experts, wasn’t initially a fan of the decorative arts in general and Tiffany in particular. “Tiffany wasn’t taken seriously,” he told Winter Park Magazine in 2014. “Nobody knew about Tiffany. Then I saw the collection and thought: ‘Oh my God! This stuff is gorgeous!’ I had no idea!”

A native New Yorker, Ruggiero held an M.A. and Ph.D. in art history from the University of Pennsylvania and an MBA in finance from Boston University. He had taught art history at the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle and later served as assistant to the president at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and executive director of the Oakland Museum Association in Oakland, California, before becoming director of the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota.

At the Morse Museum, Ruggiero oversaw the move to Park Avenue and, after McKean’s passing, led its expansion to accommodate the Tiffany Chapel. The exceedingly complex installation was designed by George Sexton, a Washington, D.C.-based consultant whom Ruggiero had hired a decade earlier to work on a top-to-bottom restoration of the Ringling Museum.

“Larry was one of the most brilliant museum directors I’ve ever worked with,” says Sexton, whose company, George Sexton Associates, maintains an ongoing relationship with the Morse Museum. “I knew this particular project would be a special experience just for the opportunity to work with him again. I would describe him as a Renaissance man.”

Mike McLeod, then a feature writer for the Orlando Sentinel, covered the project in depth through a series for the newspaper (which was later republished in brochure form) and found himself almost as fascinated with the rumpled Ruggiero as with the high-stakes project that he supervised with such single-mindedness. The two eventually developed a personal friendship.

“I just remember thinking what a perfect match Larry was for this whole thing,” recalls McLeod, now a contributing editor for Winter Park Magazine. “He was absolutely dedicated to both Tiffany and McKean. I can’t tell you how often I would hear him talk about ‘Hugh’s vision’ with both eloquence and reverence.”

McLeod describes Ruggiero as a courtly man with a droll (albeit sometimes irreverent) sense of humor and a genial manner when hosting inquisitive reporters. But when it came to the chapel and its delicate elements, he recalls, “Larry was the guard dog you didn’t want to mess with.”

During an after-hours tour of the construction site, for example, McLeod (innocently, he insists) extended an index finger in the direction of a Tiffany window: “Larry grabbed me by the arm and gave me a firm ‘no, no’ that I’ll never forget. I was just pointing—I wouldn’t have dared touch it.”

Virginia Ruggiero, whose husband of 53 years retired in February 2023 and died the following month, recalls the restoration as both exhausting and exhilarating. “Of course, Larry came home very tired, always,” she recalls. “He wanted everything to be perfect. And he was justifiably very proud when it was completed and pleased to have honored the wishes of the McKeans.”

But he was far from finished. In 2011, Ruggiero supervised the addition of a 12,000-square-foot wing for another permanent exhibition—also designed by Sexton—Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Laurelton Hall, which features 200 objects from or related to the estate as well as a re-creation of its light-drenched Daffodil Terrace. That expansion increased the size of the facility, including office space, to more than 40,000 square feet.

The Morse Museum—with Thalheimer now at the helm—receives no public funds (it never has) and continues to be owned and operated by the twin foundations. Annual attendance figures are no longer released, according to spokesperson Arielle Courtney, but it is believed that Hugh and Jeannette’s gift to the city is also its largest tourist attraction, which would likely have pleased an artist-cum-marketer like Tiffany.

In 1996, McKean was posthumously named Floridian of the Year by the Orlando Sentinel because, according to the newspaper, “he believed passionately that art and culture should be part of everyone’s everyday life—regardless of age. He felt that the soul and intellect would flourish when exposed to beauty and knowledge. To that, he devoted his life.”

Visitors can learn much about McKean at the Department of Archives and Special Collections at the Olin Library at Rollins, where there are boxes of McKean ephemera including everything from memos to articles to a polite but pointed admonition to a contractor whom he believed had been rude to his mother.

There are even dues statements for a square-dancing club and records of Winter Park’s barometric pressure, which for a time he faithfully measured using a vintage device manufactured by his grandfather-in law’s business, Fairbanks, Morse & Company. (OK, that qualifies as a quirk.)

But in one folder, there’s an untitled and undated essay, probably from the 1950s, in which he discusses his philosophy of art and what it means to the individuals who produce it. His belief in the power of art was certainly why he was so determined to share the art that he and Jeannette had collected.

“Art is a record of the artist’s discovery about life,” he wrote. “It has a special quality arising from his own experiences; it is a record of growth in his mind, testimony that he has lived thoughtfully and creatively; evidence that he has fulfilled his destiny as a man.”