Jonathan Rich and Phil Eschbach are cradle Episcopalians. After both men retired from their respective careers — Rich as a corporate attorney and Eschbach as a commercial photographer — they began spending more time than ever in church. Neither had become more devout but they had, by any definition, become evangelists.

Rather than saving souls, however, they became obsessed with saving historic Carpenter Gothic-style Episcopal churches.

You’ve likely seen these spare but elegant buildings here and there around the state: small, slender, wooden structures — usually painted white — with stained-glass lancet windows, steeply pitched gabled roofs and asymmetrically placed bell towers with spires that reach toward heaven.

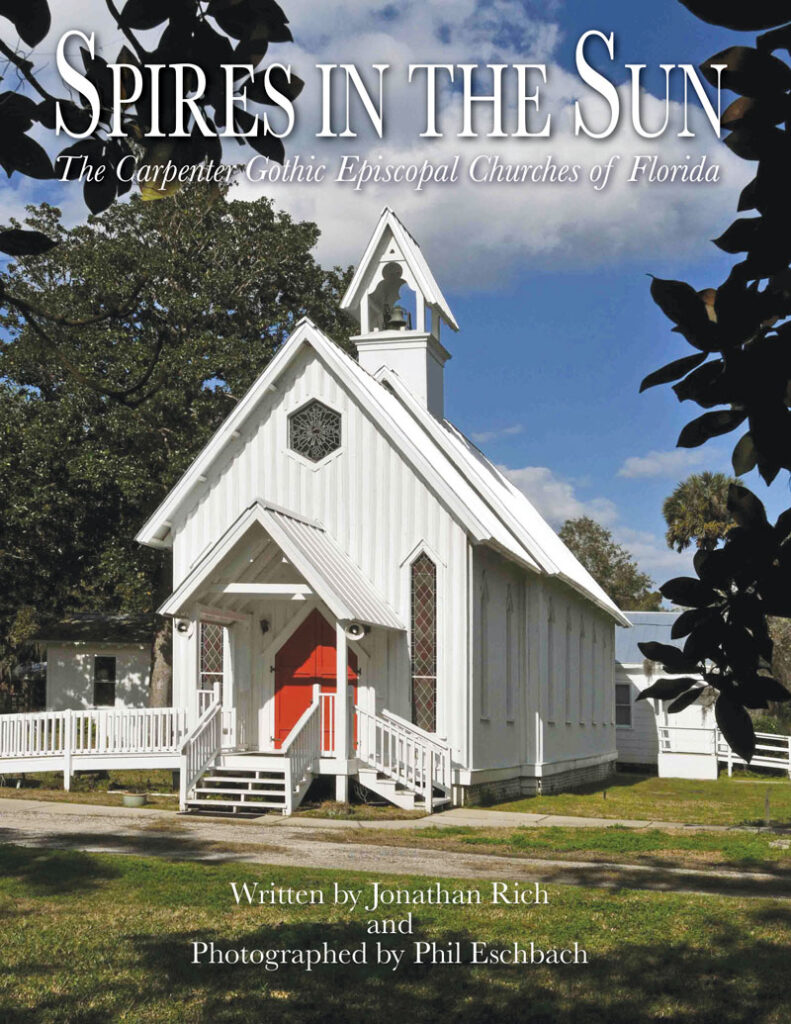

Their years-in-the-making book, Spires in the Sun: The Carpenter Gothic Episcopal Churches of Florida (Frederic C. Beil, Savannah), contains tightly written and meticulously researched histories of the 39 such churches that still survive — many of which still look essentially as they did when they were first completed.

In addition, the book offers a scholarly but accessible exploration of Anglicanism in Florida and an introduction to the indomitable characters who designed and built these surprisingly sturdy buildings in rustic subtropical outposts during the second half of the 19th century.

To tell and show it all, Rich (the author) and Eschbach (the photographer) required a 572-page tome that weighs in at five pounds. It could have been twice as long, Rich says, if they had included churches built after 1900 and churches that were still standing but drastically altered in appearance.

Recently, Rich and Eschbach have been making presentations throughout the state about their work and earning kudos from those who marvel at the sheer merit and magnitude of their achievement. In April, Spires in the Sun won the Florida Historical Society’s Charlton Tebeau Award as the best general-interest book on a topic related to the state’s past.

KINDRED SPIRITS

For Rich, the adventure started in 2005 — three years before he retired as an equity partner from the Holland & Knight law firm — when he began traveling to towns along the St. Johns River to research and photograph the distinctive little houses of worship that had fascinated him as a young man.

Sometimes, when in North Florida, he would establish a base of operations in a pop-up camper at Mike Roess Gold Head Branch State Park in Keystone Heights, since most churches he needed to visit were located within a few hours of there. “Florida has not been neglected by writers and artists,” notes Rich. “But nobody had done a book on these churches.”

At the same time, though, Rich had a busy law practice. His clients included publicly held companies, major financial institutions and Enterprise Florida, the recently dissolved public-private partnership that for three decades led the state’s economic development efforts. Today he serves as chairman of the board of Members Trust Company, a national bank that provides trust services to members of credit unions.

And his community volunteerism included presidency of the Central Florida Civic Theater (now Orlando Family Stage) and team leader for the Eatonville Initiative of The Jobs Partnership of Florida, a coalition of churches and businesses that provides workforce training in underserved communities.

Rich worked on his “project” — he hadn’t dared call it a “book” until years into the process — sporadically until he retired in 2008. Yet, although he had more time, the job of completing the work become more daunting since he had decided to include churches throughout the state, not just those near the St. Johns River.

Then, in 2014, Rich bumped into his longtime Lake Chelton neighbor, Eschbach, at the Winter Park Post Office. “I knew we were both amateur historians, so I told Phil about what I was doing,” recalls Rich, who now envisioned a definitive book richly illustrated with current and archival images. “I sprang on him the idea of joining me to do the photography. He said yes on the spot.”

Eschbach, a ninth-generation Floridian, likewise had a thriving professional life with Eschbach Photography. His civic activities had included the city’s Parks & Recreation Advisory Board, the Winter Park Public Library Board, the Tree Preservation Board, Keep Winter Park Beautiful, the Winter Park Historical Association and the Casa Feliz Foundation.

He had also published two travel photography books — The Wonders of Egypt and The Wonders of Jordan — and had written articles for historical journals on such under-the-radar topics as postal rates in Florida prior to statehood in 1845. (In 2019 he published a book, Pioneers of Florida, 1776–1860, about his ancestors, the Williams family.)

“Because I did so much architectural photography, I was interested in these churches,” says Eschbach. “I was concerned that unless there was more awareness of them, they might not be preserved. So we plotted routes, scheduled visits for when people could see us, and tried to get to two or three churches on weekends.”

During their work, the collaborators discovered that they were kindred spirits. From birth, Rich was a parishioner at All Saints Episcopal Church in Winter Park, while Eschbach, in his youth, had been a member at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Cocoa. Both churches were founded in 1886 and both were originally housed in Carpenter Gothic buildings.

(All Saints remains in the same location, but now occupies a Gothic Revival building designed in 1942 by Ralph Adams Cram. St. Mark’s, while retaining most of its original interior woodwork and stained glass, was slathered with stucco and remodeled to such an extent that it wasn’t included in the book.)

Although neither Rich nor Eschbach still attended an Episcopal church, both were steeped in the traditions of the denomination, which was formed following the American Revolution when Anglican churches in the 13 colonies declared their own independence from the Church of England.

Rich went to Holderness School, an Episcopal boarding school in Plymouth, New Hampshire. Then he majored in English at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, before earning his J.D. from Stetson University’s College of Law.

Eschbach went to St. Christopher’s School, an Episcopal boarding school in Richmond, Virginia. Then he majored in English at Sewanee — also called the University of the South — an Episcopal college in Sewanee, Tennessee, known for its highly regarded School of Theology.

During the course of researching and compiling the book — the pace of which escalated when Eschbach also retired in 2020 — the pair individually discovered personal ties to the churches that they hadn’t previously realized. “In hindsight,” writes Rich, “it seems impossible that we didn’t know about them from the beginning.”

Rich learned that his great-grandfather, the Rev. Arthur John Rich, first headmaster of the Hannah More Academy — an Episcopal boarding school for girls in Reisterstown, Maryland — had erected a Carpenter Gothic church, St. Michaels (also known as Hannah More Chapel), on the campus in 1853. It remains standing today.

He also learned that his grandfather, the Rev. Ernest Albert Rich, had moved from Maryland to Florida in 1925 to take a temporary post as rector of one of the Carpenter Gothic churches featured in the book: St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Fort Pierce. This was, as it happened, a fateful decision.

Rich’s father, John Oliver “Jack” Rich — a child during his family’s nine-month sojourn in Fort Pierce — was determined to one day return to Florida. Eight years later, he enrolled at Rollins College and, following graduation and service in World War II, became dean of admissions at his alma mater in 1949. He also married, built a home and started a family.

The elder Rich was 96 years old in 2012, when his son offered to take him to revisit the church that had made him a Floridian. Only now the sanctuary was in Satellite Beach — in 1959 it had been moved via barge up the Indian River — and was known as Holy Apostles Episcopal Church.

That poignant visit is described in the afterword of Spires in the Sun, where the younger Rich writes that his father — despite not having set foot in the building for 87 years — remembered many details and even noted that different stained-glass windows had been installed.

“He placed his hand on the pulpit where his father had preached,” the account continues. “Shaking his head, he looked back at me, his pale blue eyes watering. ‘Sometimes nowadays, my dreams are so lifelike,’ he said. ‘I can’t tell them apart from reality anymore. Then he smiled and added, ‘But if this is a dream, it’s a good one.’”

Eschbach, in the meantime, discovered that he was the great-grandnephew of Charles T. McBride, one of the founders of Holy Trinity Church in Melbourne (1885), where stained-glass windows that the McBride family donated can still be seen.

He also learned that he was the second cousin three times removed of the Rev. William Eppes, rector of Christ Church in Monticello (1886), and an even more circuitous relative of Lewis and Margaret Seton, founders of St. Margaret’s Church in Fleming Island (1875), which is thought to be one of the smallest churches in Florida.

All three churches still look pristine, and Spires in the Sun tells their stories. Holy Trinity, in particular, describes one of several potential happy-ending scenarios for jewel-box buildings that have outlasted their utility as a congregation’s primary meeting place.

When Holy Trinity’s membership outgrew the original sanctuary on Free Avenue in the late 1950s, a new one was built about a mile further inland on West Strawbridge Avenue. The old building was deconsecrated and neglected but, fortunately, not torn down.

In the early 1960s, the women of the church raised the funds needed to move the structure to the Strawbridge campus, where it was renovated and has been in use for more than 60 years as a chapel and event venue.

Episcopal church congregations were (and are) overwhelmingly white. But Spires in the Sun does spotlight a church that was originally built for a congregation of African Americans, who by and large were far more likely to affiliate with less formal and more demonstrative denominations.

St. Mary’s Episcopal Church (originally St. Philip’s Episcopal Church) in Palatka was built in 1883 as an outreach of nearby St. Mark’s Episcopal Church. Writes Rich: “In Palatka, at the turn of the century, St. Mary’s was a church of the nation’s emerging [Black] gentry.” Both St. Mark’s and St. Mary’s remain in use as houses of worship.

In Jacksonville, the Kidane Mihret Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church was built in 1885 as All Saints Episcopal Church in Huntington, a now-forgotten unincorporated community near Palatka. The building was barged to Jacksonville’s west side in 1971 and was bought by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in the early 2000s.

The church’s founders, writes Rich, would be “dumbfounded, and no doubt thrilled to learn that the church [building] was presently owned by a congregation of African Americans who, unlike the grove workers they had once known and helped in Huntington, were educated, independent and equal under the laws of their adopted land.”

But what about Central Florida? The region has its share of Carpenter Gothic churches: Christ Episcopal Church in Longwood (1880), Church of the Holy Spirit in Apopka (1886), Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Fruitland Park (1888), Christ Church Episcopal in Fort Meade (1889), St. James Episcopal Church in Leesburg (1889) and St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Haines City (1894).

And then, in our immediate vicinity, there’s Church of the Good Shepherd in Maitland (1883), where services were led by the Rt. Rev. Henry Benjamin Whipple, first Bishop of Minnesota whose advocacy for Native Americans and work among the Dakota and Ojibwe tribes had earned him international acclaim and a nickname from tribal leaders: “Straight Tongue.”

Whipple, in poor health by the 1870s, wintered in Maitland with his wife, Cornelia. He personally bought the property for Church of the Good Shepherd, selected the architect and preached there every season for the rest of his life. “Man,” Whipple once wrote, “being essentially active, must find in activity his joy, as well as his beauty and glory; and labor, like everything else that is good, is its own reward.”

In 1967, the congregation built a new church — designed by Nils M. Schweizer, a former protégé of Frank Lloyd Wright — alongside the lovingly restored original building, which is now used as a chapel and boasts 18 original stained-glass windows donated by the Diocese of Minnesota to honor the founding rector and his family.

There are as many stories as there are churches, and Rich has told them in a way that perhaps only a research-savvy attorney whose literary skills transcend the ability to compose cogent legal briefs could have done.

In his prose — which is weighty with facts and insights — Rich also finds several occasions in which to wax philosophical, as he does when pondering the eventual fate of the churches featured in Spires in the Sun:

“If it is true that we are losing our instinct for public beauty, it follows that we might be capable of lapsing into failure to protect legacies like our Carpenter Gothic churches without even realizing it.”

He continues: “It strikes me as a reason to be doubly prudent when we think about making changes to the churches. Perhaps only by renewing our commitment to their preservation can we expect to pass on to future generations the traits that made them exceptional to begin with.”

And Eschbach has enhanced Rich’s stories with his photography, which makes it easier to visualize the distinctive (perhaps divine) architectural features described in the text and to marvel at the beauty of the stained-glass windows and intricately carved altars, baptismal fonts and prayer desks.

Exteriors are shown in the context of their surroundings — usually quite tidy — while interiors evoke the scent of stained heart pine and the feel of volume in spaces that usually seated only 50 or so worshipers. As Rich describes them, the churches “radiate an ineffable dignity and repose” that Eschbach has effectively captured with his lens.

A VISION FULFILLED

Call them obsessive — they wouldn’t deny it — but Rich and Eschbach cumulatively drove thousands of miles to meet with church archivists, to rifle through dusty files and to tromp through rustic cemeteries looking for the final resting places of prominent church founders.

At St. James Episcopal Church in Leesburg, they even shimmied beneath the building wielding flashlights to see for themselves if the floorboards, scorched in a long-ago fire, had really been turned over and reused as had been claimed. (They confirmed this was true.)

Yet, despite their passion for this particular topic, both Rich and Eschbach are the kind of people who are interested in everything — and are, therefore, interesting people apart from their encyclopedic expertise on frontier church architecture in Florida.

Rich, who with his wife, Beth, has three adult children and six grandchildren, has been a gold-medal winning rower in the USRowing Masters National Championships, and head of the Crew Boosters of Winter Park and the Millennium Rowing Association, both of which support the crew program at Winter Park High School.

Eschbach, who with his wife, Elizabeth, has two living adult children (a son died in 2005) and one grandchild, was a top-ranked tennis player in college — he still plays and has shared the state doubles championship several times — and an avid horseman. He has staged photography exhibitions throughout the region, including a series at the Winter Park Library.

Coincidentally, the fact that Spires in the Sun exists at all as a physical book in such an impressive (and expensive to produce) format is thanks to Episcopalian contacts and connections.

The Rev. Canon H. Douglas Dupree of the Episcopal Diocese of Florida suggested a publisher to Rich and Eschbach: Frederic C. Beil in Savannah. Turns out, both Dupree and Beil were Eschbach’s classmates at Sewanee. Beil, enchanted by the project, told the pair: “I want to fulfill your vision for the book.”

Music to an author’s ears! A contract was signed in 2021 and only then, after years of work, did Rich and Eschbach know for certain that their massive collection of stories and pictures — “a love letter to Florida,” as Rich describes it — would see the light of day.

“If I’d known then what I know now, I probably wouldn’t have started this,” says Rich, who at times thought the manuscript might simply gather dust in an archive somewhere. “This book was the hardest thing I’ve ever done.”

But he’s gratified, he adds, to return to the churches that he had visited — some of them perhaps years earlier — and share with amazed parishioners the resulting product.

Eschbach says he, too, was prepared for the possibility that a book might not be in the offing. “We told ourselves that we might end up sending it to Rollins, UCF or the University of Florida and that would be it,” he says. “But for me, either way it was a chance to engage my professional know-how and to do it my way artistically.”

Most important, both agree, is that Spires in the Sun illuminates these surviving architectural gems of Florida’s past and, hopefully, enhances appreciation of them and bolsters efforts to preserve them. Writes Rich: “If this book were to play even a slight role in the churches’ rediscovery and reevaluation, our efforts will have been rewarded.”

Spires in the Sun is available at the All Saints Gift Shoppe, 338 East Lyman Avenue., Winter Park, or may be ordered via jaxcathedralbooks.org.

A DENOMINATION WITH TASTE AND TREASURE

Why were so many Carpenter Gothic Episcopal churches — perhaps more associated in the public mind with New England — built in Florida, of all places?

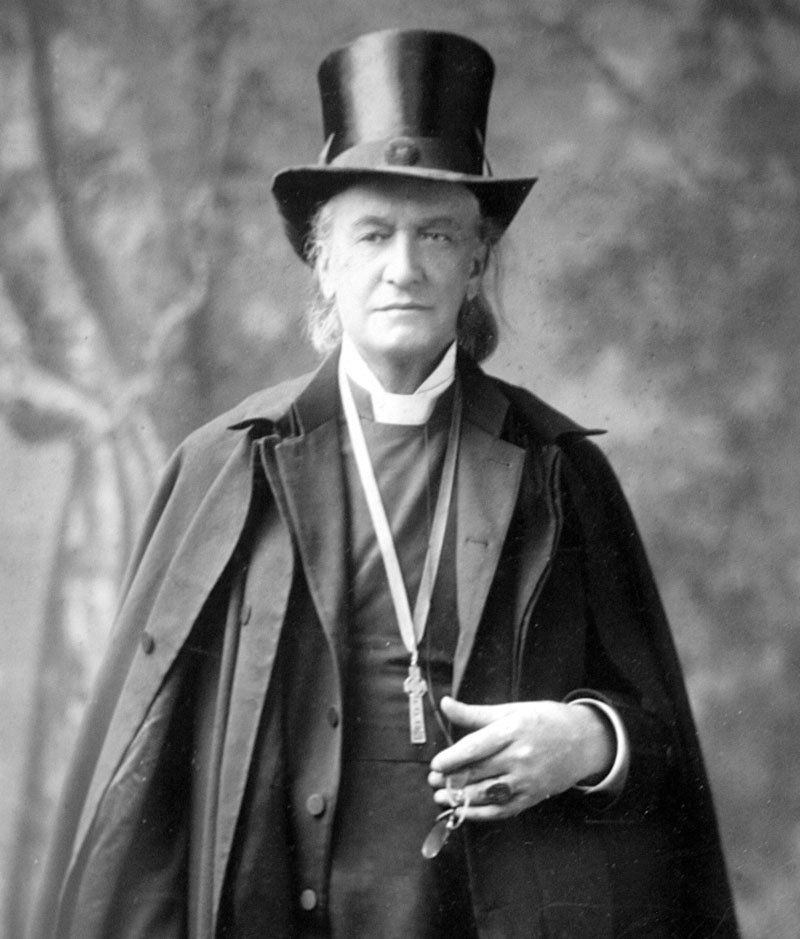

According to Spires in the Sun, chief credit goes to the Rt. Rev. John Freeman Young, who, straight out of seminary in 1845, was appointed as a missionary to East Florida and served from St. John’s Episcopal Church (now St. John’s Cathedral) in Jacksonville.

After assignments in Texas, Mississippi, Louisiana and New York, Young became the second Episcopal Bishop of Florida in 1867 and began establishing mission churches along the St. Johns River in areas where communities were sprouting up thanks to access via steamboat.

His task was complicated, especially during the first decade, by devastation wrought by the Civil War. Ultimately, however, more than 25 Episcopal churches were established during his episcopate as Northerners were increasingly attracted to Florida.

One of those responsible for Florida’s allure was Harriet Beecher Stowe (Uncle Tom’s Cabin) a supporter of Young’s who, with her husband, Calvin, moved to Mandarin, planted a citrus grove, established an integrated school and sang the state’s praises in Palmetto Leaves, a series of essays that were published and widely read.

The Stowes also helped found Church of Our Savior in 1883, which was built in a style that Rich describes as a “close cousin” to Carpenter Gothic. The church building — which contained a stained-glass window by Louis Comfort Tiffany, an admirer of Stowe’s — was destroyed by Hurricane Dora in 1964.

A larger new church was built as well as a side chapel that included the old church’s salvageable fixtures and stained-glass windows — except, sadly, for the Tiffany window, which did not survive the storm.

Still, writes Rich, Our Savior is included in Spires in the Sun — an exception to his rule that a church had to remain standing to qualify — because of Stowe’s historical importance and the church’s preservation of other stained-glass windows in the chapel.

Digression aside, the Carpenter Gothic style was popularized in Upjohn’s Rural Architecture, a “pattern book” of plans and specifications published in 1852 by Richard Upjohn, a British cabinetmaker who had emigrated to the United States.

Upjohn, who emerged as a leading architect of the American Gothic Revival genre, designed New York City’s Trinity Church Wall Street, which was completed in 1846. Young, who had been assistant rector there prior to his return to Florida, worked with Upjohn, who was the official architect of Trinity Parish.

In his pattern book, Upjohn offered an approach that he insisted “should come within the means of the feeblest congregation yet be, in all its essential features, a church — plain indeed but becoming in its plainness.”

While other denominations used the Carpenter Gothic style, it was most strongly associated with the Episcopal denomination, which was responsible for its earliest, purest and most numerous expressions.

Considering a church no less than a “standing sermon,” 19th-century Episcopalians refined their church-building into a scholarly discipline, “ecclesiology,” which studied medieval Gothic architecture, art and furnishings to determine which elements were most deserving of latter-day imitation.

The reason so many Carpenter Gothic Episcopal churches have survived? They were well designed and well built. The relatively wealthy Episcopalians invested accordingly — an average of $3,780 per church for their first 10 churches in Florida versus about $707 per church spent by the Baptists, Methodists and Presbyterians.

FAITH ON THE FLORIDA FRONTIER

Spires in the Sun celebrates deceptively simple ecclesiastical architecture.

By Maurice O’Sullivan

While popular history often sees Spain’s and Portugal’s colonization of the New World primarily as a quest to gain wealth in order to expand the power of their empires, the language of both kings and conquerors focused as much on converting the indigenous peoples to Christianity — and more specifically, to Catholicism — as on discovering El Dorado or the Seven Cities of Gold.

To celebrate that faith, Spain and Portugal filled their New World colonies with stunning churches and cathedrals from Quito’s La Compañía and Brazil’s São Francisco de Assis in Ouro Preto to Mexico City’s Catedral Metropolitana de la Asunción de la Bienaventurada Virgen Maria and Peru’s La Merced.

But not in Florida. Sherlock Holmes was right that an absence can tell us a great deal. The lack of any significant colonial ecclesiastical architecture in the Sunshine State is only one more reminder of how marginal we were in the Spanish empire.

In 1586, Sir Francis Drake burned St. Augustine’s first modest and poorly built Catholic church, and its replacement, made of straw and palmetto, burned even more easily in 1599. Another British raid in 1702 destroyed the third, far sturdier Catholic church, after which the parish of St. Augustine opted to hold its masses in the city’s hospital rather than invest in rebuilding.

It wasn’t until almost a century later, in 1793, during the second Spanish Period, that the parish — the oldest in what is now the United States — finally committed to build a new church, which eventually became a cathedral in 1870. The void that Catholics left in Florida’s ecclesiastical architecture became an opportunity for their theological cousins, the Episcopalians.

Although the state’s first Episcopal diocese wasn’t established until 1838, throughout the rest of the century this American branch of the Anglican community filled Florida with a remarkable number of distinctive, memorable houses of worship.

These places are beautifully described and richly celebrated in Spires in the Sun: The Carpenter Gothic Episcopal Churches of Florida (Frederic C. Beil, Savannah), by Winter Park residents Jonathan Rich, writer, and Phil Eschbach, photographer.

Like England’s largely stone Gothic Revival churches, Carpenter Gothic began as a compromise. During the Victorian Age, the Church of England sought an architectural style that could distinguish it from the simplicity of such Nonconformist communities as the Presbyterians, Congregationalists and Calvinists by reminding worshipers of the established church’s antiquity and grandeur.

The country’s growing wealth allowed it to build magnificent houses of worship that could inspire awe with their spires, soaring walls and towers, steeply pitched roofs, pointed arches, ribbed vaults and beautifully designed stained-glass windows.

The Gothic reconstruction of the Houses of Parliament at Westminster, begun in 1837, was a parallel attempt both to remind the nation of its glorious historic traditions and to discourage the growing populist revolutionary wave sweeping through Europe.

In the American Northeast, Episcopalians followed the English tradition by building Gothic churches that could fit comfortably into any wealthy British community.

For example, when the Episcopal Diocese of New York began the third version of its Trinity Church facing Wall Street in 1839, it designed a Gothic Revival structure made of Monson granite and Longmeadow sandstone that would become the tallest and one of the most elaborate buildings in the United States.

The frontier offered different challenges, as Spires in the Sun describes. Without the wealth and physical resources of the industrial North, Southern states — and especially Florida — turned to the area’s abundant lumber rather than stone and brick.

While the term Carpenter Gothic has been used widely to describe a variety of styles, Rich and Eschbach focus their work on a distinctive tradition: small, wooden churches that reflect the legacy of Anglican ecclesiology and the influence of Richard Upjohn and Frank Wills — British architects who emigrated to the United States — and their American Gothic Revival contemporaries.

The first part of the book tells the story of the rise of Florida’s Anglican community and its churches, largely through the second half of the 19th century.

Along with detailed discussions of the period’s carpentry and transportation, theology and ecology, Rich’s graceful, allusive prose offers a rich history of how one denomination survived, expanded and helped define the southernmost state’s evolution as it emerged from the Civil War. Rich also offers an extensive discussion of the architects who established and refined both Gothic Revival architecture and its offspring, Carpenter Gothic, in the United States.

The second and far longer part of Spires in the Sun focuses on the development of 39 of these churches, perhaps a fairly subtle allusion to the Church of England’s foundational 39 Articles.

These stories center on the individuals and communities that brought each church to life and the ways in which distinctive architectural features reflected the values and culture of the state’s increasingly diverse communities. Framing that history as part of pilgrimages that Rich and Eschbach make to each church reveals how these sacred spaces continue to serve as both portals to the past and inspirations for the present.

One important theme throughout the book is the essential role of women as prime movers in developing congregations in their communities, organizing campaigns to build churches for those communities and finding the funds for construction.

The most notable among them was Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of the 19th-century’s most popular novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The only church discussed in the book’s second part that no longer exists is the Church of Our Savior in Mandarin — the one that Stowe helped to create.

In addition to more than 100 pages of notes, a bibliography and an index, Spires in the Sun includes two invaluable additional sections at the end. A color-coded index identifies churches that have been substantially preserved, churches that have been preserved but modified, churches that have been substantially modified and churches that are now lost.

And for those unfamiliar with either ecclesiastical architecture or the finer points of religious practice and history, a glossary offers an excellent guide to the curious nuances of Anglican belief and practice.

Mixed among the book’s rich archive of historic photos, Eschbach’s photographs capture the churches’ deceptively simple elegance. His cover image of St. Paul’s Church in Federal Point, for example, reveals a tall, slender, milk-white church and its startling red doors dappled with light and shadows framed by a slightly cloudy sky and vigorously blooming trees — a complex scaffolding that foreshadows the stories to come.

Everything about St. Paul’s points to heaven, from the narrow vertical boards on its siding with their triangular battens to the series of sharply pitched angles formed by the doors and the gabled roofs over the porch, the building itself and the belfry. Even the two stained-glass windows and their wooden frames rising protectively next to the entrance doors echo those acute angles.

Spires in the Sun is a wonderful contribution not only to our state’s history but to those who prize handsome books. Elegantly written, beautifully designed and splendidly illustrated, it suggests why, in our increasingly digital world, so many people continue to value physical books as objects of awe and inspiration.

While clearly a labor of love and faith, Jonathan Rich and Phil Eschbach have created a superb historical document — the definitive account of our state’s humble yet profound Carpenter Gothic churches, which are truly enduring treasures.

Maurice “Socky” O’Sullivan is the Kenneth Curry Professor of Literature Emeritus at Rollins College, where he has taught since 1975. He has published a dozen books and more than 100 articles, essays and columns on topics that range from religion to Irish culture to Florida history. In 2019, the City of Winter Park proclaimed March 17, St, Patrick’s Day, as Maurice “Socky” O’Sullivan Day.