The High Victorian train station on what is now the National Mall was virtually empty when the president and his secretary of state walked inside to catch a train north. But on this steamy July day in 1881, the president would not make his train. Instead, James A. Garfield was shot twice by a disgruntled madman.

Garfield would spend the next two months in agony as inept doctors rummaged around his organs looking for the bullet, and his insides became infected. Then he died. For weeks, the nation, the memory of Lincoln’s assassination still fresh, waited.

Waiting was all they could do, and that went for Vice President Chester A. Arthur, too. Thanks to the gunman, Charles Guiteau, a shadow hung over a man who was a national afterthought. Upon completing his long-fantasized revenge, Guiteau was reported to have joyfully declared, “Arthur will be president now.”

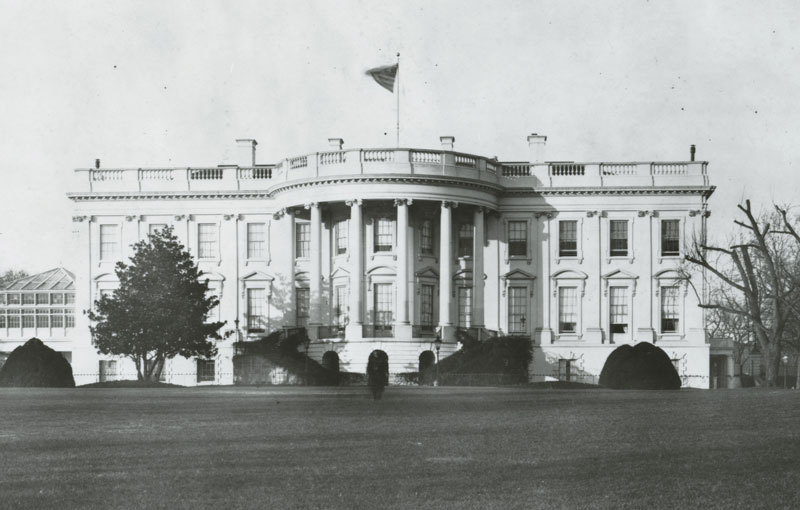

Arthur did become president, and shocked the nation with how seriously he took on reform. But official Washington was in for a more intimate shock. Upon arriving in the capital to assume the presidency, Arthur said of the White House, “I will not live in a house like this.”

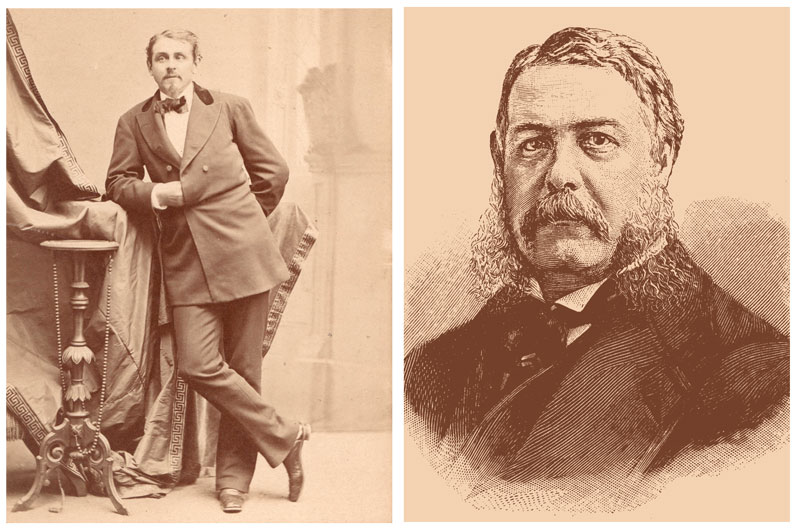

Instead, he hired the country’s star interior designer, Louis Comfort Tiffany, to transform the White House into an elaborate and over-the-top spectacle you needed to see to believe.

There were disco-ball Islamic wall sconces, gold and silver splashed about and a multicolored giant glass screen that glittered like a dragon’s hoard. Almost all of it, including an object now considered one of the most valuable in White House history, is completely lost.

In the long list of people who were never meant to be in charge but were put there by fate, Chester A. Arthur was really, truly, completely never-supposed-to-be president.

A machine-politics operator who had never been elected to public office, the only thing he was known for was being pushed out as head of the U.S. Custom House in New York when it was engulfed in a corruption scandal.

In this era of weak presidents, Arthur was a lieutenant for one of its true powers — U.S. Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York, who controlled a wing of the Republican Party known as the Stalwarts.

When Conkling and company failed to get former President Ulysses S. Grant the 1880 nomination (for a third term!), dark-horse candidate Garfield was selected, and to bring the party together his team’s second choice for vice president was Arthur. Thinking Garfield would lose and damage the brand, Conkling opposed it.

But Arthur, clearly more self-aware, had aspirations so low that when offered a job famously described as worth less than “a warm bucket of piss,” he told the vituperative senator, “The office of the vice president is a greater honor than I ever dreamed of obtaining.”

The outrage within the party of somebody so tainted by corruption being named vice president was quelled by the reality that the vice president had no power, and it was impossible to imagine that Arthur would ever advance beyond it.

But on September 19, 1881, the man who was supposed to be the country’s most forgettable vice president became one of its most forgettable presidents.

A Diva President

Arthur was perhaps our most diva president. He had as many as 80 suits, all made custom by a New York tailor. They came in handy, as this man who was born in a log cabin was known to make multiple outfit changes daily and to wear a tuxedo to dinner.

He worked only a few hours a day and held parties and dinners until the wee hours of the morning. Arthur was heavy-set and got around D.C. on a leather-trimmed carriage adorned with his coat of arms painted in gilt, lamps of silverplate, gold lace curtains and a lap robe of otter fur lined with green silk. It was pulled by horses draped in blankets with the gold-thread monogram C.A.A.

He brought to the capital a French chef, and his New York City townhouse had a sitting room decked out in white and gold. Upset that the elevator he had installed in the White House was too simple, he had it redone in tufted plush.

One need only look at his baronial presidential portrait to see that this was the Gilded Age president with all the airs to mirror those of the newly wealthy of New York, Philadelphia, Chicago and San Francisco.

Like any good New Yorker with pretensions, Arthur was a customer of Tiffany & Co. and made his way to the Park Avenue Armory to see the new Veterans Room designed in 1881 by Louis Comfort Tiffany (the son of Tiffany’s founder, Charles Lewis Tiffany) and his team, which included Stanford White, Francis Millet, Candace Wheeler and Samuel Colman.

The Armory, a former military headquarters, is now a cultural facility run by the Park Avenue Armory Conservancy, a nonprofit organization. The architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron restored the opulent Veterans Room, one of the few surviving Tiffany-designed interiors, in 2015.

When Arthur saw the state of the White House — after its decor had been ignored by staid party poopers like Rutherford B. Hayes and then partially turned into a hospital at the behest of Garfield — he decided a redecoration reflecting the country’s status was required and that there was really only one man for the job.

“Arthur was a tastemaker, and he knew what the current [design] trends were,” says Jennifer Thalheimer, director and chief curator of the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art on Park Avenue and an internationally renowned expert on Tiffany.

“The country was still recuperating from a lot of pain at that time,” she adds, referring to the Civil War and the trauma of Reconstruction. “Arthur wanted the White House to be a rejection of the past and to reflect a brighter, more optimistic outlook.”

This was a widely shared outlook, increasingly reflected in posh private homes across the country. As urban American families in the 19th century accumulated large amounts of wealth, they looked for ways to spend it that would show off their lucre: clothes, jewels, art and homes.

The homes began to be designed by professional architects in a variety of styles rather than by builders in just a handful of aesthetics, and wealthy Americans clamored for interiors that made as much of a statement as the exteriors.

Consequently, by 1881, interior decoration was undergoing a revolution. For decades, the interiors of grand homes had been done up by furniture and cabinet makers, the most prestigious of which was Herter Bros., who designed the interior of the largest residence in New York City history — the mansion of Cornelius Vanderbilt III.

Artists as Decorators

The craftsmanship in such upper-class homes was top notch, but the flair and artistic quality were generally uninspired. And with the advent of easily disseminated photographs and magazines showing how each house was one upping the other, an interior with flair was very much in need.

At the same time, there was significant infighting at the National Academy of Design (now the National Academy Museum and School of Fine Arts), an honorary association founded in New York City in 1825 “to promote the fine arts in America through instruction and exhibition.”

Tiffany — an accomplished easel painter — was a member of the academy and showed his work there. But he was also the most prominent in a group of young artists who rebelled against the organization’s selection policies for exhibitions and explored the decorative arts as an equally valid — and more commercial — means of expression.

“There was so much crossover,” says Thalheimer. “An artist, such as a muralist, could also be doing homes.” Plus, she notes, Tiffany’s father was a merchant, not an artist. Perhaps that’s why his son seemed more keenly aware than many of his purist peers that art and commerce (or art and utility) need not be mutually exclusive.

In many ways, Tiffany was a kindred spirit to Hugh McKean, the former Rollins College president who with his wife, Jeannette Genius McKean, founded the Morse Museum and stocked it with works that they had salvaged from Laurelton Hall, the artist’s ruined estate on Long Island.

Hugh McKean — an artist who in 1930 had won a Tiffany Fellowship to study at Laurelton Hall — wrote that Tiffany himself hated the phrase “fine art … [his] entire life was a revolt against this precious attitude.” He was, instead, determined to show that the lesser arts of design and decorative objects could be equally worthy of admiration by art snobs.

Life at Laurelton Hall was certainly inspirational to McKean, who later described the 84-room home and the 580 acres surrounding it as “a three-dimensional work of art, fabricated of marble, wood, plaster, winds, glass, copper, rains, light, sound, sunlight, flower gardens, running water, terraces, woods, hills.”

McKean also recalled the magnetism of Tiffany himself, who at age 82 spent evenings with his students, offering kindly critiques of their work and “talking about the importance of beauty … I thought he was wonderful.” Which undoubtedly made it all the more painful to know that the iconic artist’s work had fallen so far from favor.

But Tiffany was still all the rage in 1879, when he launched a decorating company with the painter Samuel Colman and textile designer Candace Wheeler called Louis C. Tiffany and Associated Artists. The upstart artists quickly became the designers, a status reflected in how many of the homes in that era’s design bible, Artistic Houses, were theirs.

Tiffany was an “artistic decorator, not a regular interior decorator,” says Thalheimer. “He’s going to put art in your home and surround you with beauty and new ideas and the most cutting-edge stuff.”

Today, however, there are only two places where you can experience the Tiffany team’s residential work largely intact: Mark Twain’s house in Connecticut and the aforementioned Park Avenue Armory Veterans Room.

(There is also the Ayer Mansion, built in 1902 in Chicago’s Back Bay area. However, the 15,000-square-foot home — most recently used as a dormitory for a women’s religious group — is currently for sale and is expected to once again become a private residence.)

But you need only visit the Veterans Room to get a sense of Tiffany’s interior-design aesthetic.

It is an orgy of materials and patterns so complex and detailed that your eyes cannot rest with its intricately carved wood screens, a fireplace of blazing Silk Road blue and elaborate stencil work that covers every inch. Arthur is believed to have visited this room before making his decision to enlist Tiffany to redo the White House.

While hard to imagine now — indeed, to even acknowledge now that the People’s House is anything other than perfect is politically dangerous for presidents — the White House’s occupants often thought it to be sorely lacking, with little to no privacy, filled with rats, poorly furnished and in danger of collapsing.

Lucretia Garfield had been appropriated some money for a redecoration, but it was never completed, which left the house in disarray with unfinished pipes laying around, half-done carpentry and paint jobs, and naked windows.

When Arthur assumed the presidency, he stayed at the home of his friend Senator John P. Jones of Nevada rather than the White House and used the Garfield sums to finish the decoration that they had started.

But he began visiting daily to inspect the space with the head of the government engineering office. And he was startled by what he found.

What a Dump

The report put together from these inspections was scandalous. Servants’ quarters were so dank they caused sickness, and the kitchen’s chipping whitewash often fell into pots of food.

Worse, the White House was quite literally sitting on a pile of human excrement as the pipes for several of the toilets had decayed so that waste ended up under the basement. The State Dining Room, of all places, still had chamber pots.

The report was submitted to Congress, and the Senate actually passed a bill for a few hundred thousand dollars for the White House to be torn down, replaced with a replica for executive offices and a new residence built to its south. But that plan died, and Arthur realized that if he was to have a grand home he would have to work with the existing building.

In May of 1882, Tiffany, then 34, met with Arthur at the White House and agreed to redo the East Room, Red Room, Blue Room, the State Dining Room and the Transverse Hall. The Green Room would be left untouched.

For this herculean task, which needed to be completed in six months, Tiffany would be paid a flat fee of $15,000, which was three quarters of what he had made for the single room at the Armory.

But as historian Wilson H. Faude, first curator of the Mark Twain House, explained, “few commissions as important as the White House existed,” and “any changes to its interiors would be noted and imitated by other decorators and clients.”

To ready the White House for Tiffany’s vision, Arthur went room by room deciding what would stay and what would go. A total of 24 wagons laden with what would today be priceless furnishings — including Andrew Jackson’s writing desk — went out for auction.

Tiffany brought a crew from New York that was willing to work day and night with only the president allowed to visit. Although much had been auctioned off — the buyers included former President Hayes, who snared the dining table from the State Dining Room — plenty of objects remained, and Tiffany had to incorporate or work around them.

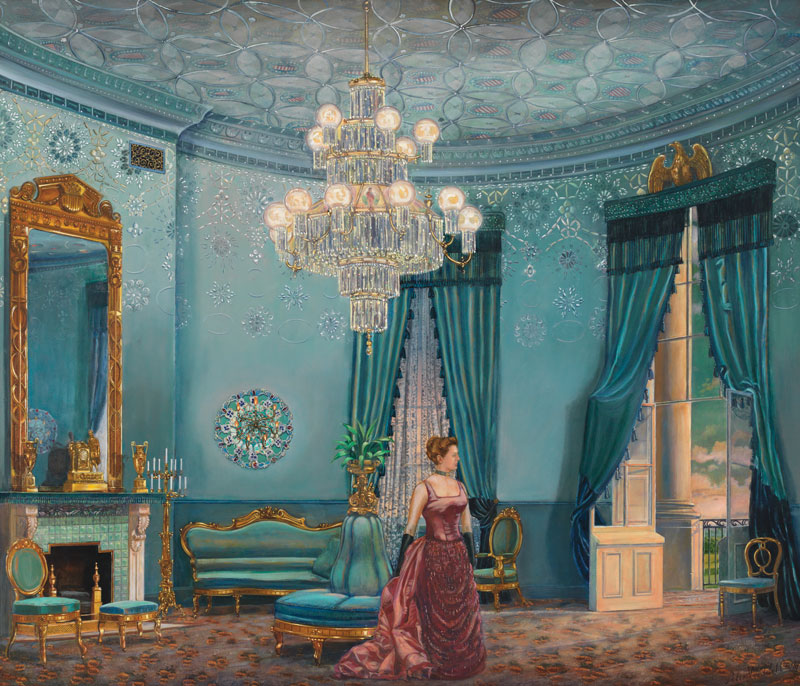

The thematic room colors also had to remain, and so while blue — light blue in particular — was an unpopular color, “the Blue Room was suffered to remain a blue room,” sneered Artistic Houses. That undersells what Tiffany got away with — something that is hard to fathom even with photographic evidence and colored renderings.

The Blue Room is where the president received the credentials of foreign diplomats and greeted guests. Oval in shape, Tiffany found it an ideal form to play off the idea of a robin’s egg.

If you were to visit in the daytime, which few did, it would have seemed a sort of sickly green, but under gaslight at night, when most events were held, it was a brilliant blue. (As a protege of the painter George Inness, Tiffany was notable for his precision with the effects of different types of light.)

Tiffany was a “dye-in-the-wool Republican,” Robert Koch writes in Louis C. Tiffany: Rebel in Glass, “and proud of having decorated the White House for President Chester A. Arthur.” So on the ceiling of the Blue Room, he went full nationalist.

A doily-like allover pattern with white and silver interlocking ovals covered the ceiling, and at the center of each oval were the red, white and blue stars and stripes shield of the White House. Below the ceiling was an 8-foot-wide frieze of hand-embossed silver and gray patterns that resembled snowflakes.

The color on the wall gradually darkened from the silvery frieze to robin’s egg blue to a dark blue wainscoting. The curtains were also dyed to have three separate bands of color to match the walls. On the existing fireplace, Tiffany added squares of opalescent glass.

But the real shocker was hanging on the wall: four circular sconces influenced by Islamic design. Each was a 3-foot-wide rosette of hundreds of pieces of mirrored and colored glass that provided a backdrop for seven unshaded gas jets, the arms of which were dripping with pendants of iridescent glass.

The sconces, writes Koch, “must have beamed like disco balls.” One journalist remarked in his coverage that these balls were “wrinkled in order to catch light from many angles.” Thus was a stately and dour room transformed into something scintillating and fun, and so overwhelming that you’d (hopefully) not notice the gilt Louis XV revival furniture and the circular divan.

If the Blue Room was a sparkling showpiece, it was the Red Room where Tiffany really flexed his colorist muscle. It’s a space in which the designer seems to say, “Oh, you want red? I’ll give you red!”

“When first I had a chance to travel in the Near East and to paint where the people and the buildings are also clad in beautiful hues, the preeminence of color in the world was brought forcibly to my attention,” Tiffany would later say.

He continued: “I returned to New York wondering why we made so little use of our eyes, why we refrained so obstinately from taking advantage of color in our architecture and our clothing when Nature indicates its mastership.”

For the Red Room, Tiffany continued with the idea of color gradation. The walls were painted a sumptuous Pompeiian red that verged on claret while the wainscoting was a darker almost currant color. The frieze was verging on pink and covered in an abstraction of stars and stripes. The wood trim was also covered in a dark red paint but rubbed until it was glossy.

Already drowning in red, Tiffany added two more elements that would have left one gobsmacked. The first was the fireplace, and for that he had the pre-existing white marble one ripped out and replaced with one of cherry designed by Art Nouveau master Edward Colonna.

Around the opening was a mosaic of glass tiles colored amber and red to enhance the flickering flames within. Around those were panels of Japanese leather tinted red and set into the cherry.

Above the mantel but below the existing mirror was another glass mosaic, this one with embedded glass gems. And the original gilt mirror was framed in red plush upholstery. The ceiling was the other scene stealer, as Tiffany had it painted with circles of bronze and copper stars on a gold background, varnished such that any bit of light was reflected.

Most of the furnishings were pieces that Tiffany repurposed, whether candlesticks from President James Monroe’s administration, a silk screen gifted by Austria to Ulysses S. Grant or an office clock used by Abraham Lincoln.

Tiffany also kept a series of Sèvres vases from France peculiarly decorated with scenes of the conviction and sentencing of Charlotte Corday (assassin of Jean-Paul Marat). As for the piano found there, one critic wrote: “For its presence I believe the decorators are not responsible.”

But the artist wasn’t some whirling decorating dervish throwing sparkle everywhere. In the State Dining Room, he understood that there would normally be lots of flowers, fancy dresses and a shiny dining service — so he kept things simple.

The walls were painted yellow (fawn, to be specific) and a series of hammered silver reflectors were added to gas brackets to lighten the space. The ceiling and frieze were painted primrose and lemon with rosettes.

The largest of the state rooms is the East Room, and here Tiffany was also restrained as the walls had recently been redone in white and gold. He brought in new objects like Turkish chairs and circular divans as well as a sienna-colored Axminster rug.

On the ceiling, William Seale writes, Tiffany decorated it with squares colored rust, gold and brown to resemble old wallpaper and match the amber window hangings. Artistic Houses described it at the time as a “small mosaic pattern, in silver-leaf, which easily receives the reflection of the carpet.”

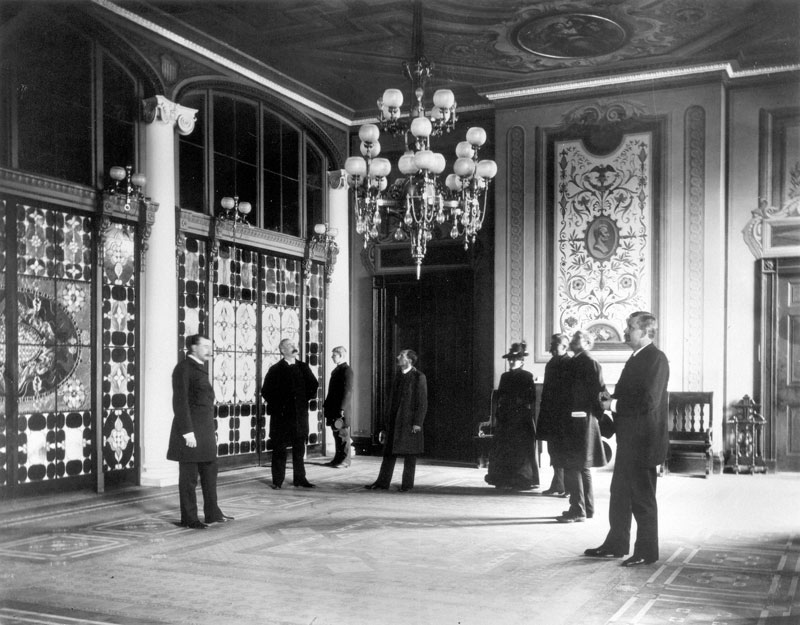

While Tiffany’s designs for the rooms of the White House were a spectacle, one addition was undoubtedly the most famous: his glass screen separating the entrance hall from the transverse hall which ran along the Red, Blue and Green Rooms and connected the East Room with the staircase.

The screen, theoretically, gave the president and family some privacy from guests in the entrance. In the White House, the existing screen of smoked glass had been put in place in the 1850s, and before that it was a screen (unsexily named the “draft eliminator”) installed by White House architect James Hoban.

Tiffany was already a prolific glassmaker, and his kaleidoscopic leaded glass curtain was immediately seen as a masterpiece. A variety of shades of red, white and blue were splashed between the four ionic columns.

With walls painted a cream color and a ceiling “stenciled with a silvery network like a spiderweb,” writes William Seale, the “stained glass made the long hall continually iridescent.” It had an effect, Century Magazine declared, that was “rich and gorgeous.”

Looking through photos of Tiffany’s theatrical White House designs, the screen is the sole element that looks like it truly belongs with its surroundings. It was especially spectacular during state dinners, as tables were placed alongside its gem-like expanse.

Whimsy, Sparkle and Surprise

For months, the only outside person who had been able to see the work was Arthur, but on December 19, 1882, a press preview was held. The reaction was mixed. One newspaper crowed, “No longer is the White House simply the home of a Republican president. Lo, it is the temple of high art.”

“Tiffany, a romantic,” another said, “had added whimsy, sparkle and surprise to a stately classic building.” One reporter described the Red Room as “overpowering” in “richness and antiquity.”

Of the screen, most were effusive, with one declaring, “It is so much better than any glass which can be produced in Europe today that the typical American should point to it as one of our surest titles to respect when enumerating them for the benefit of the typical foreigner in Washington.”

Tiffany reportedly saved all the clippings, good and bad. One negative review he would likely have held onto was in New York’s The World:

“[Tiffany’s decorations] are not ideally good by any means, not ‘monumental,’ not ‘high art’ at all. In spite of all the abuse that has been heaped upon it, the White House is a fine old mansion, extremely well-planned for its purpose — except as to staircases — and being capable of being made into a beautiful building. It ought to be decorated someday from end-to-end in a truly good style with the best products of the chisel and the brush.”

Perhaps the most cutting was in Artistic Houses, where the author damned by faint praise: “The beauty and artistic value of the Messr. Tiffany’s decorations are best appreciated by those guests who know how the White House used to look.”

As far as Washington society went, the rooms were by and large a hit. Even Mrs. Blaine, the trenchant wife of former Secretary of State and perpetual presidential aspirant James Blaine was forced to concede. What she referred to as “the White House taint” was gone and instead it showed “the latest style and an abandon in expense and care.”

But if Tiffany’s rise as a designer was rocket-like, his fall was even faster. Just a few years after the White House was completed, the heavy, busy and crowded “Victorian clutter” that he enacted was out.

While Tiffany’s glass and decorative art are considered extremely valuable today, in the years before his death they were passé. Just seven years after he finished his White House overhaul, First Lady Caroline Harrison — wife of President Benjamin Harrison — was undoing some of his work and planning to build an entirely new residence.

While her plan was torpedoed by a vengeful congressman, it resurfaced at the turn of the century with proposals for an expansion or entirely new residence. “No little plans,” was Washington’s mantra in this period, an attitude best captured by palatial proposals for the president’s residence and the National Mall.

But after yet another assassination, this time President William McKinley, another accidental president dramatically reshaped the White House. Teddy Roosevelt and First Lady Edith turned to the senior partner in the world’s biggest architectural firm, Charles McKim of McKim, Mead & White.

“Roosevelt felt that the White House needed a standard, more enduring aesthetic,” says Thalheimer. Indeed, McKim’s restoration would be merciless to Tiffany’s work. When it came to the iconic glass screen, he famously sneered, “I would suggest dynamite.”

Plus, it might be assumed, a character like the Rough Rider — who at Sagamore Hill, his private residence, displayed animal-skin rugs, a rhino-foot inkwell and the mounted heads of taxidermied creatures that he had killed on expeditions — found the existing ambiance entirely too ethereal for his tastes.

Beginning in 1902, McKim removed nearly all traces of Tiffany’s work and sold off the furniture. When he was tasked with the job, McKim proposed to “take [the White House] down stone by stone … and rebuild it; and not another architect in the country can make a finer or more appropriate residence for the President of the United States.”

He turned the White House into the paragon of Colonial American decor we associate it with today, but with an elegance on par with European palaces.

As to those who lamented the lost pizzazz of Tiffany, The New York Times went on the attack, declaring that the critics were upset by “the simplicity and moderation, the chastity and good taste, which belong to the restoration of a Colonial Mansion.”

The Times further contended that naysayers were simply chafing at the “absence of that ‘palatial magnificence’ which is to be found in so many hotels and so many steamboats and so many barrooms.”

The Judgment of History

But in a morality play of what goes around comes around, McKim’s overhaul would also fail to stand the test of time. Yet another accidental president, this time Harry S. Truman after Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s death in 1945, would redo the White House. This time it was a full gut job down to just its shell.

A decade later, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy’s version of Colonial design (a “restoration” not redesign, she emphasized) would ultimately win out.

As for that Tiffany glass screen? It reportedly ended up in a Baltimore hotel and disappeared for good when the hotel burned down in 1923. Tiffany died 10 years later, his work disparaged by the arts cognoscenti as gaudy and his glassworks sometimes available for purchase in second-hand shops.

Then, in 1957, after Laurelton Hall was destroyed by fire, Hugh and Jeannette McKean were invited to come to Long Island by the artist’s daughter — who knew of Hugh’s long-time admiration and knowledge of her late father — to salvage what was left from this once-magical place.

The McKeans accepted at once and purchased, for a modest price, everything that could be saved among the debris, and hauled it back to Winter Park in moving vans.

History has not been particularly kind to Arthur, who remains a largely forgotten figure about whom a consensus has emerged that he was, without question, a mediocre president — but perhaps a better one than most expected. Tiffany, however, is a household name and has reclaimed his place among America’s most acclaimed artists.

If any institution ought to stage a retrospective exhibition related to Tiffany’s decoration of the White House, it ought to be the Morse Museum. The only problem is, there is nothing to show. “Every once in a while, we hear a rumor that something has survived,” says Thalheimer. “But it hasn’t turned out to be true.”

William O’Connor is a former senior editor at The Daily Beast where he oversaw its travel section. Originally from Newport, Rhode Island, he has long been fascinated with the history of American architecture and design.

Chet Was Here: President Arthur and Winter Park

The so-called “Accidental President” — the dandy from New York who assumed office when President James A. Garfield was shot down, lingered for 11 agonizing weeks and finally died in 1881 — has only a peripheral (and coincidental) connection to Winter Park through his hiring of Louis Comfort Tiffany to redecorate the White House.

But he has a few direct ties, too. Arthur became the first sitting president ever to visit Winter Park and, before that, the first person to receive a telegraph message from the city.

The president’s Florida sojourn was in April of 1883, and was taken at the behest of Hamilton Disston, an industrialist and real estate developer whose efforts to drain the Everglades started the state’s first land boom.

Arthur declared that “Florida mosquitoes are not so bad as Washington office seekers” and managed to work in some fishing while in the Sunshine State.

He was said to have shown flashes of “bad humor” during the trip, no doubt because — unknown to the public — he was ill and slowly dying of Bight’s disease, a kidney ailment now known as nephritis. Nevertheless, he powered through the tour while avoiding much of the fanfare that a presidential visit would normally entail.

Arthur and his entourage had traveled via a private train from Washington, D.C., to Jacksonville, then took a steamboat up the St. Johns River to Sanford, where Secretary of the Navy William E. Chandler reportedly shed his coat and climbed an orange tree to pick some fruit, a delicacy at the time.

The presidential party stayed in the 200-room Sanford House, owned by Henry S. Sanford, a diplomat and citrus grower who founded the town for which he was named. Arthur, though, insisted on taking his meals in a private dining room and made no public appearances, much to the frustration of local residents.

A private car owned by the South Florida Railroad then transported the contingent to “Kissimmee City,” where Arthur — a guest of the Tropical Hotel — viewed Disston’s dredging of the Kissimmee River and did some angling on Reedy Creek.

From Kissimmee City, Arthur and company traveled by rail to Maitland, where the president visited with his friend, Judge Lewis H. Lawrence, a wealthy boot and shoe manufacturer originally from Utica, New York, who would later become instrumental in the founding of Eatonville.

Lewis wished to show Arthur his groves along the northern shores of Lake Maitland, so a party of 20 or so took buckboards to Winter Park. A reporter described what he saw as “a very pretty town … pretty little cottages [are] on the banks of the lakes, such as are seen at Northern seaside resorts.”

Arthur, the scribe notes, “always dresses elegantly” and “appeared becoming in a straw hat and a new summer suit.” But the bumpy ride was probably miserable for him. Bright’s disease is often accompanied by fatigue, sweating, cramps and nausea.

Also accompanying Arthur and Lewis was Loring A. Chase, co-proprietor with Oliver Chapman of Chapman & Chase, developers and promoters of the New England-style town on the Florida frontier. Chase was eager to wring whatever promotional value he could from the presidential visit.

To some extent, he succeeded. Upon returning from the grove, Arthur and his entourage agreed to stop in front of the Rogers House Inn, located on the southeast corner of Morse Boulevard (then called simply “The Boulevard”) and Interlachen Drive, where the president was greeted by schoolchildren bearing flowers and ladies serving lemonade.

Arthur briefly visited Town Hall (then on the second floor of Ergood’s Store on Park Avenue), which was festooned with flowers, but told Lawrence — who had coordinated the schedule with Chase — that he was “too nervous” to make any public remarks.

Still, the assembled crowd offered a hearty three cheers before the ailing guest of honor took his leave aboard the presidential train. “The quiet and simple manner of his reception here brought forth warm expressions of praise from the president,” wrote a reporter.

The dispatch continued: “[Arthur] remarked that he had seen nothing prettier since he left Washington and would like to get away from the crowd and sit for a week under the grand old pines and rest.”

His sanguine mood would not last. The train was scheduled to stop briefly in Orlando, but “after a little exhibition of temper” by the president, no stop was made, “much to the disgust of the citizens of Orlando, who had fully prepared to make the first visit by the President of the United States to their town a memorable occasion.”

Arthur returned to the capital on April 22 via an ocean voyage on his yacht, the Tallapoosa. He heard from Lawrence again on January 1, 1883, when he received a locally significant telegraph message from his friend that read: “Happy New Year. First message from office opened here today. No North. No South.”

The “Gentleman Boss,” a clearly less pejorative nickname than the “Accidental President,” died just six months after leaving office at age 57.

—Randy Noles

Fascinating Clutter: All That Fussy Stuff Makes Perfect Sense

Picture the interior of a Victorian home. It’s hard to know where to look — let alone how to be comfortable — in that jumble of curios and knickknacks that many today would consider junk.

But it all had a purpose, which the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art explores in Fascinating Clutter — American Taste During the Reign of Victoria. The exhibition opens Tuesday, October 17, with no closing date set at press time.

The term “clutter” references stereotypes about the period, particularly regarding interior design, according to the museum. Such maximalism can seem overwhelming in light of today’s streamlined decorative styles. But Victorians on both sides of the pond used their living spaces to communicate both their aesthetics and ideological outlooks.

Queen Victoria occupied the throne from 1837 to 1901, and her reign acts as a framing device for a range of design trends.

The exhibition focuses on the period from around 1850 to the 1890s — a time when the United States and Great Britain enjoyed close cultural connections. But both were also experiencing intense technological, industrial and economic change — including globalization and a rapidly rising middle class during the second half of the century.

Fascinating Clutter encompasses more than 100 items, from paintings of bucolic scenes to ornate domestic furnishings to vintage bling such as shimmery jewelry. It also provides context for Art Nouveau and the Arts and Crafts movement, both of which were reactions to Victorian excess.

People of the 19th century outfitted their homes with items that conveyed who they were and how they saw themselves in a rapidly changing and disorienting world. Those who look past the clutter can see into the emotions and psyches of the people of the time.

“Far from a cacophony, one may hear a chorus where each layer plays a major or minor key, offering a visual spectacle far greater than the sum of its parts,” the museum notes. “Fascinating Clutter offers visitors a true, if transient, sense of appreciation for something long ago that feels like home.”

The Morse Museum is located at 445 North Park Avenue, Winter Park. For more information, call 407-656-5311 or visit morsemuseum.org.

—G.K. Sharman