Popular music’s icons and cult heroes usually earn their status traveling a rutted back road of poverty, substance abuse, tragedy and premature death. Sometimes, though, they come from affluent families, live relatively happy lives and die heroic deaths.

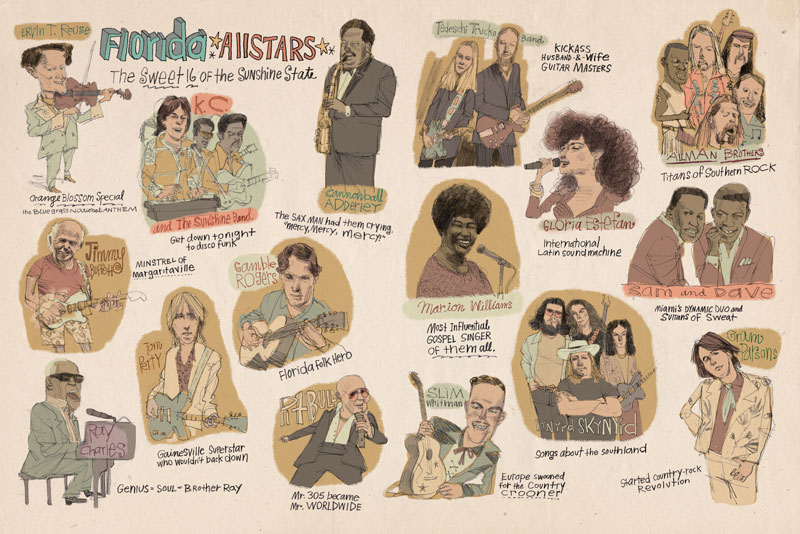

Each is the case for a pair of legendary figures who have Winter Park ties. Last spring, Tampa-based Florida Humanities, the statewide affiliate for the National Council for the Humanities, decided to choose the 16 greatest musical stars ever to have roots in Florida and to announce them in Forum, the organization’s excellent quarterly magazine.

Lo and behold, two of the 16 had connections to Winter Park — a place known more as a hotbed for orchestral and choral music than for folk, country, rhythm ‘n’ blues and rock ‘n’ roll.

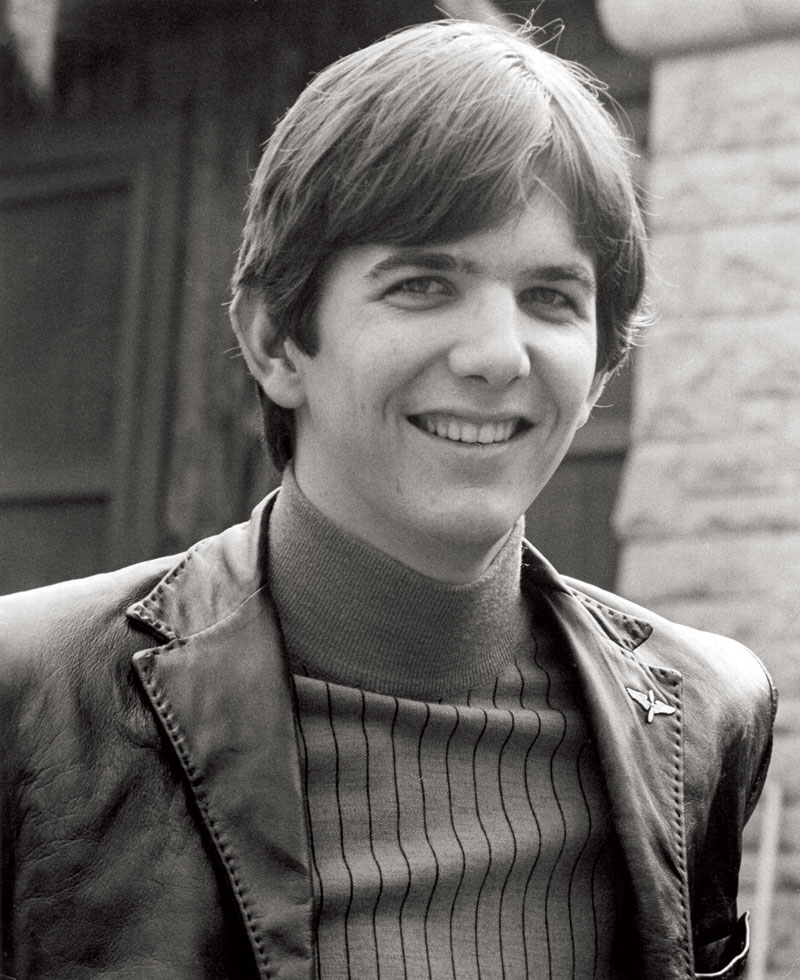

One of 16 selectees, Gram Parsons, lived here only briefly, but at a pivotal time during his development as a pioneer (some would say the progenitor) of a hybrid genre called country-rock.

The other, James Gamble Rogers IV, a local native, became an exemplar of folk music known as “Florida’s Troubadour” and a favorite of NPR listeners for his agile storytelling.

“Florida has a rich and exciting musical legacy, from the songs of Indigenous people to the electrifying riffs of some of the world’s greatest rock guitarists,” says Pam Daniel, editor of Forum, who with other magazine contributors cast a wide net in her search.

Continues Daniel: “As our stories came in, we found ourselves taking guilty breaks from editing to listen to the mesmerizing music and artists our writers were describing. I came to appreciate more than ever the magnetic power of music — as well as its ability to provoke controversy.”

Controversy, in this case, because Florida’s musical heritage is so rich and diverse that the process of picking out a handful of standouts would unavoidably overlook numerous worthy luminaries. That’s the nature of such lists.

In addition, Daniel and her team tried to include not only universally acknowledged greats but also more obscure figures who were important but not particularly well-known beyond hard-core pop musicologists. Perhaps there’ll be a few who are new to you. You can see the entire group, rendered by illustrator Regan Dunnick, on pages 34 and 35.

In any case, Winter Park was well represented.

FLORIDA’S TROUBADOR

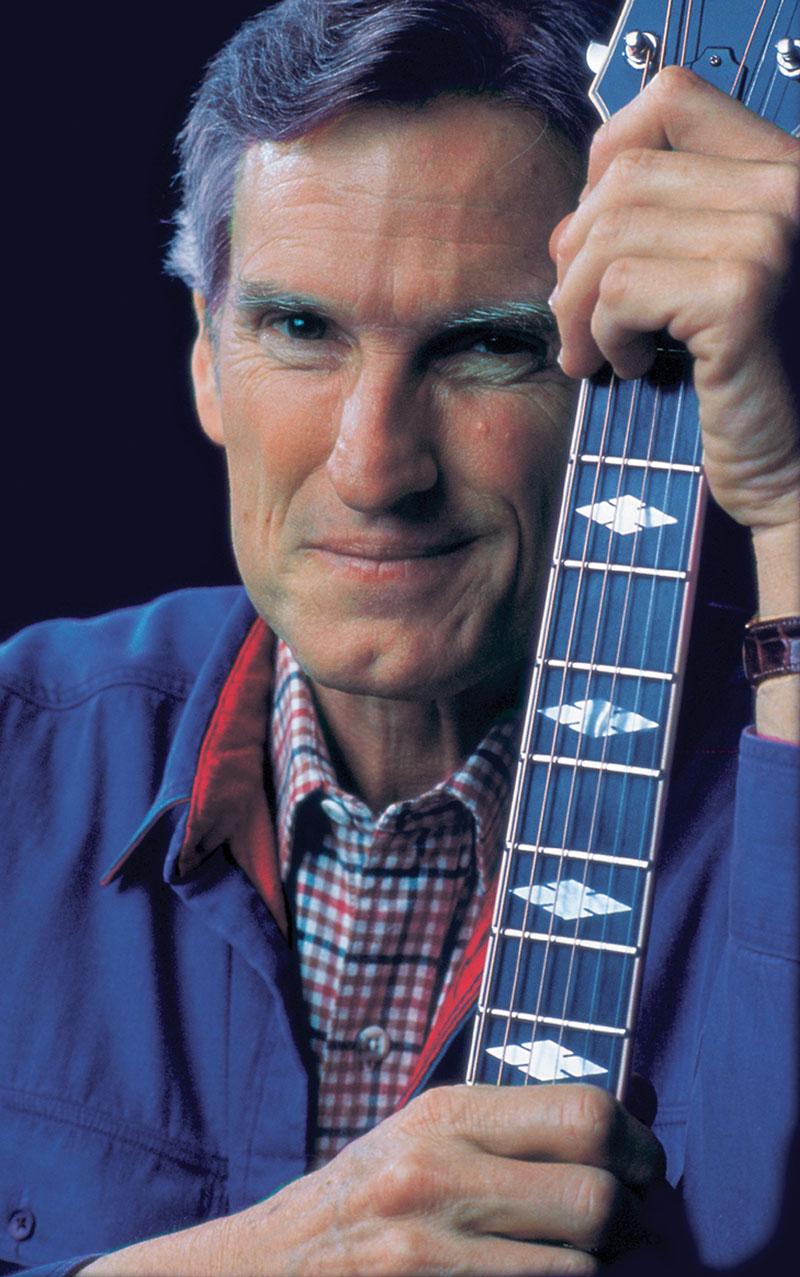

James Gamble Rogers IV was the son of Winter Park’s most renowned architect. Yet, he spurned the family business and became a troubadour, celebrating rural Florida with whimsical stories, evocative songs and skillful fingerpicking.

For nearly 30 years, he presented a genre-defying one-man show that took him from raucous bars to intimate listening rooms to the stage of Carnegie Hall. In doing so, he left a musical legacy as enduring as any of the buildings designed by his father. Or, for that matter, by other family members who likewise became notable architects.

The name James Gamble Rogers III went not to the son of James Gamble Rogers II — the folk singer’s father — as might be expected, but to a grandson of the first James Gamble Rogers, who was an architect in New York. (Indeed, the family has produced six architects named James Gamble Rogers.)

Gamble’s brother, more conveniently (and less confusingly) named Jack, became chairman and CEO of Rogers, Lovelock & Fritz (now RFL Architects in Baldwin Park), the firm their father founded.

Known in his youth as “Jimmy,” the ever-gallant Gamble died in the Florida surf in 1991, trying to save the life of a Canadian tourist he’d never met. It was an act of bravery that those who knew him say was entirely in keeping with his character.

Now, 32 years later, friends and family still display a mixture of affection, reverence and unresolved grief that causes them to tell the story of his death as if the outcome somehow still hung in the balance; as if this time it might end differently.

Should all this seem too mythic for any flesh-and-blood human, then welcome to the world of Gamble Rogers, who treated his fans as though they were the stars, and he had all the time in the world to visit with them.

Distinguished by clear diction and a reedy timbre, Gamble sang like he spoke, using a cultured Southern dialect. His vocals were punctuated by energetic thumb-picked bass lines and buoyed by arpeggio guitar flourishes.

No less a storyteller when he was singing than when he was speaking, Gamble favored songs with narratives. He often challenged his own artistic range, performing songs with story lines that were funny, poignant, heroic or dissolute.

For his tall tales, he painstakingly composed serpentine, alliterative, mock-scholarly sentences and then practiced them before a mirror until he could deliver them in long, energetic bursts. Audiences would start chuckling at the first laugh line, not knowing that seven more would come before the passage ended.

It seemed to his fans as though Gamble was holding forth from the loading dock at Arrandale’s Purina Store in Oklawaha County, the fictional Florida backwater in which many of his stories were set.

Lanky, angular and six feet tall, Gamble dressed in a dignified but unpretentious manner for the stage, sporting wool blazers and brown Florsheim Imperial cap-toe shoes.

His work ethic was prodigious and his presentation was, at turns, frenetic, poignant and sardonic. A tireless performer, he wanted to give his audiences their money’s worth and then some — but still leave them wanting more.

If the bred-in-the-bone gallantry of a Southern gentleman can be a tragic flaw, it would be about the only one anyone ever found in Gamble. His manners were old-fashioned and courtly, and he was patient and generous with his audiences.

GAMBLE’S GUITAR

Chicago-based folk singer Michael Peter Smith, who

died in 2021, wrote a haunting and poignant song,

“Gamble’s Guitar,” about his friend. Here’s a snippet:

Behind Spanish walls in Winter Park,

In the smell of jasmine in the dark,

Running a speed trap outside Starke,

I thought I heard Gamble’s guitar.

Whole lot of country, whole lot of blues,

Whole lot of sunshine, sand in your shoes,

Sound of a player who paid his dues,

Put some miles on that Mustang car.

Shot of Merle, jigger of Chet,

Little bit of Will McLean, I bet,

Only the wind in the palms and yet,

I thought I heard Gamble’s guitar.

Friends and fellow artists describe Gamble as someone who had achieved a near-seamless blend of life and art, combining technical excellence with sincere humility, wry humor and a writerly love for language.

Born in 1937 to energetic and sophisticated parents, Gamble grew up in a loving family of Renaissance-style high achievers. His father, in addition to being an architect, was a world-class swimmer and skilled musician.

If it seems strange that the son of a prominent architect in a wealthy city could be so convincing in his depictions of rustic characters and remote places, brother Jack has an explanation: They were raised like country boys.

The Rogers clan lived on 18 acres called Temple Grove, now an upscale subdivision but then a working orange grove. The brothers came into Winter Park to sell fruit to the Marketessen, a small grocery store on Park Avenue.

Gamble and Jack spent summers on a north Georgia farm owned by their mother’s family. Listening to stories told by farmhands inspired Gamble and helped shape his stage persona.

Back home in Winter Park, the pair often took to the water, once embarking on a 2.5-mile canoe trip up Howell Creek (then referred to as Snake Run) from Lake Osceola to Lake Howell. They also camped on Dog Island and hunted ducks along the St. Johns River. Like all siblings, they scuffled among themselves from time to time. But everyone knew that if you picked a fight with one brother, you picked a fight with them both.

Then came a serious medical crisis that tested Gamble’s resolve and shaped the man he was to become. At age 14, he attempted a high jump and missed the sawdust pit, jarring his spine on hard ground.

The accident aggravated a serious but previously undiagnosed case of spinal arthritis, triggering a lifelong struggle with limited mobility and chronic pain.

For therapy, Gamble had to lie on a large stainless-steel reflector, under a heat lamp, for four hours a day. He passed the time practicing the guitar — a record player and a collection of Merle Travis albums was always nearby — and reading. Although his condition was a serious one, he refused to use it as an excuse for failing to accomplish a goal.

As a Boy Scout, for example, Gamble was one merit badge away from attaining Eagle Scout status. The missing badge was for athletics, which was out of the question, so the scoutmaster offered permission to substitute three other badges involving less strenuous activities. Gamble refused, not wanting any special accommodations made for his benefit.

After graduating from Winter Park High School in 1955, Gamble enrolled at the University of Virginia. While there, he met several times with Nobel laureate William Faulkner, the school’s writer-in-residence, whom he idolized and was inspired by.

At the end of his junior year, Gamble decided to skip final exams and left Charlottesville to take guitar lessons from jazz guitarist Charlie Byrd in Washington, D.C. Notes Jack, with his family’s gift for ironic understatement, this resulted in his brother being “excused from the University of Virginia, for at least a year.”

Back in Winter Park, Gamble enrolled at Rollins College, where he befriended English professor Edwin Granberry, author, essayist and mentor of Margaret Mitchell, who wrote Gone With the Wind.

Granberry composed a glowing recommendation that helped his young protégé get into DeLand’s Stetson University, which had a writing program that the venerable O. Henry Award winner thought would be ideal for his talented student.

Gamble spent a year at Stetson before putting aside formal higher education for good. He had drifted through four years at three different colleges, majoring in architecture, English and philosophy. Yet he had no degree to show for his effort.

Again he returned to Winter Park and ensconced himself in his parents’ guest house, where he spent the better part of a year working on a book before declaring that he simply wasn’t ready to write anything worth reading.

He later worked for a year in his father’s architecture office, where he displayed an intuitive gift for design. Jack believes that his brother could have been a top-tier architect, although only one of his designs was built — the Orange County Juvenile Detention Center, in which he used bulletproof glass instead of bars.

Nothing, however, could deter Gamble from performing. He played locally at Dubsdread, Harrigan’s, the Beef & Bottle and a coffeehouse at Rollins.

He also appeared at folk clubs in surrounding cities, most notably the El Prado Lounge in Winter Garden and Stuckey’s Saloon in Lakeland, where he was often joined by friends Paul Champion, a banjo player, and Jim Ballew, a guitarist. Locally, he played at the Carrera Room, located first on Park Avenue and later relocated to Orange Avenue, where The Porch restaurant and sports bar now sits.

But in a family of achievers, was such an esoteric career path acceptable? “Our parents, especially our dad, understood pretty well,” says Jack. “My mother was flexible. Neither of them tried to discourage him. But we had uncles who would say, ‘When are you going to get a real job?’ Jimmy would just walk out of the room when that happened.”

Gamble and friends Champion and Ballew moved to Tallahassee and opened a downstairs grotto club called the Baffled Knight. Those three, who called themselves the Baffled Knights, were the house act.

By 1966, although Gamble was a seasoned performer, fame had continued to elude him. So he took a trip to Massachusetts, where he planned to interview for a job at Cambridge Seven Design, a respected architecture firm.

If architecture was indeed his destiny, then at least he needed to establish an identity away from Florida, outside his father’s substantial shadow. “I think he would have taken the job,” says Jack.

The fact that he instead wound up joining a nationally known singing group instead was, well, serendipitous.

While in Massachusetts, a friend persuaded Gamble to take a side trip to New York City to watch auditions for the Serendipity Singers, a popular folk group that had reached the Top 10 with “Don’t Let the Rain Come Down (Crooked Little Man)” two years earlier.

Gamble, unimpressed with mediocre showings from the other musicians in attendance, borrowed a guitar and ambled onstage. Although it was a spur-of-the-moment performance, he was offered a job singing and playing lead, acoustic and electric guitars.

Because of Gamble’s storytelling skills, he also became the group’s front man, setting the scene for their songs when they appeared on such network mainstays as The Tonight Show, The Ed Sullivan Show and Hootenanny.

Success offered Gamble a sense of validation, but he soon began to feel restless and out of place. “I was merely a hired gun, so to speak,” he told the Orlando Sentinel in 1987. “I simply signed on with an already established group.’’

He left the Serendipity Singers after two years to pursue a solo career, relocating to the Coconut Grove neighborhood of Miami, which had a thriving folk-music scene. From there, he built up a circuit of coffeehouses and clubs in St. Augustine, Gainesville and Tallahassee.

Finding that well-crafted acoustic songs weren’t always enough to hold a rowdy crowd’s attention, Gamble further honed his storytelling, which would later be described as a combination of Mark Twain and Will Rogers — if either humorist had been a Floridian.

By the early 1970s, Gamble was playing across the United States and Canada. In 1974, when he appeared at the Philadelphia Folk Festival, PBS taped his performance for nationwide broadcast.

The following year, the network produced a television special: Gamble Rogers: Live at the Exit In, which originated in Nashville.

Indeed, Gamble’s literary bent and subversive approach to Southern humor seemed tailor-made for PBS. He was a current-events commentator on NPR’s All Things Considered in 1976 and 1977 and then again in 1981 and 1982.

One of his monologues, “The Great Maitland Turkey Farm Massacre of 1953” was included in Susan Stamberg’s book, Every Night at Five: The Best of All Things Considered. The riotous recitation can still be heard on YouTube.

Gamble also wrote two NPR radio dramas, Good Causes: Confessions of a Troubadour, which aired in 1977, and Earplay, which aired in 1980. A Gamble-scripted television play, The Waterbearer, aired on PBS in 1984 and was rebroadcast twice in 1985.

In the fall of that year, Gamble co-hosted and performed on AT&T Presents Carnegie Hall Tonight, which followed a concert appearance at Carnegie Hall with the legendary Doc Watson, a bluegrass icon. It was, as far as anyone remembers, the only time Gamble ever performed wearing a tuxedo.

In part because of his PBS affiliation, Gamble gained a following among intellectuals, who appreciated his facility with language and his ability to satirize both rural ignorance and urban pretension in pointed yet hilarious ways.

What differentiated Gamble from dozens of would-be Woody Guthries? It had to be the stories.

Rogers enlivened his tales of life in Oklawaha County and Snipes Ford, the county seat, with the antics of a host of colorful characters, most notably “Agamemnon Abramowitz Jones,” “Downwind Dave” and “Sheriff Hutto Proudfoot.”

Snipes Ford, where “sorriness” was considered a prime virtue, had little of the precious charm of Lake Wobegone, Garrison Keillor’s frozen outpost of Lutheran virtue “where all the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the children are above average.”

By contrast, in Snipes Ford, the center of community activity was the Terminal Tavern, a scurrilous dive “where the good ol’ girls put their earrings on with staple guns and the good ol’ boys know it’s always easier to get forgiveness than it is to get permission.”

In the last decade of his career, Jack says, his brother seemed to have hit his stride. He was flying to gigs instead of piling more miles on his Mustang, and living happily in St. Augustine with his free-spirited wife, Nancy.

He packed clubs and was welcomed as a superstar at folk festivals and storytelling gatherings. He was a niche celebrity, perhaps, but a celebrity nonetheless. And, most importantly, he was doing exactly what he wanted to do, exactly the way he wanted to do it.

One weekend in 1991 at Flagler Beach, the 53-year-old folkie and his wife returned to their campsite from a four-hour bike ride, tired and ready to go home. The October daylight was waning, heavy weather was coming in and the surf was head-high and dangerous.

The Halloween Storm, a three-hurricane hybrid that sank the sword fishing boat Andrea Gail and inspired Sebastian Junger’s bestselling novel, The Perfect Storm, was only a few days away.

It was no day for swimming, but a tourist from Ontario had gone into the water and gotten into trouble. His young daughter ran to Gamble, pleading for someone to help her father. His arthritis, relentlessly worsening since childhood, had frozen his spine so severely that he’d struggled in the calm water of a swimming pool just weeks before.

Gamble had to know that he couldn’t maneuver in the surf on his own. Yet he stripped to his undershirt and shorts, grabbed an air mattress from beneath a sleeping bag and started into the water.

As the minutes ticked by, park ranger Chuck McIntire, a strong swimmer, joined Gamble and another would-be rescuer. McIntire swam past Gamble, who signaled to him that he was still alright.

As McIntire continued outward, working the undertow to reach the Canadian, a massive wave ripped Gamble’s air mattress away. His body was found a few hours later.

Tributes poured in from friends and fans. Jimmy Buffett dedicated his Fruitcakes album to Gamble’s memory: “I dedicate this collection of songs to a troubadour and a friend who has gone over to the other side where the guardian angels dwell and has, in all likelihood, become one.”

The state Legislature honored Florida’s quasi-official musical ambassador by creating the Gamble Rogers Memorial State Recreation Area, a 144-acre park on Flagler Beach between the Atlantic Ocean and the Intracoastal Waterway.

St. Johns County opened Gamble Rogers Middle School near St. Augustine in 1994, and the Division of Cultural Affairs named Gamble to the Florida Artists Hall of Fame in 1998. This year’s Gamble Rogers Folk Festival — the 27th — is set for April 14 through 16 at the St. Johns County Fairgrounds.

Gamble is buried in Winter Park’s Palm Cemetery. Nancy, who died of cancer in 2005, is buried beside him. The marker above them reads: “Florida’s Troubadour.”

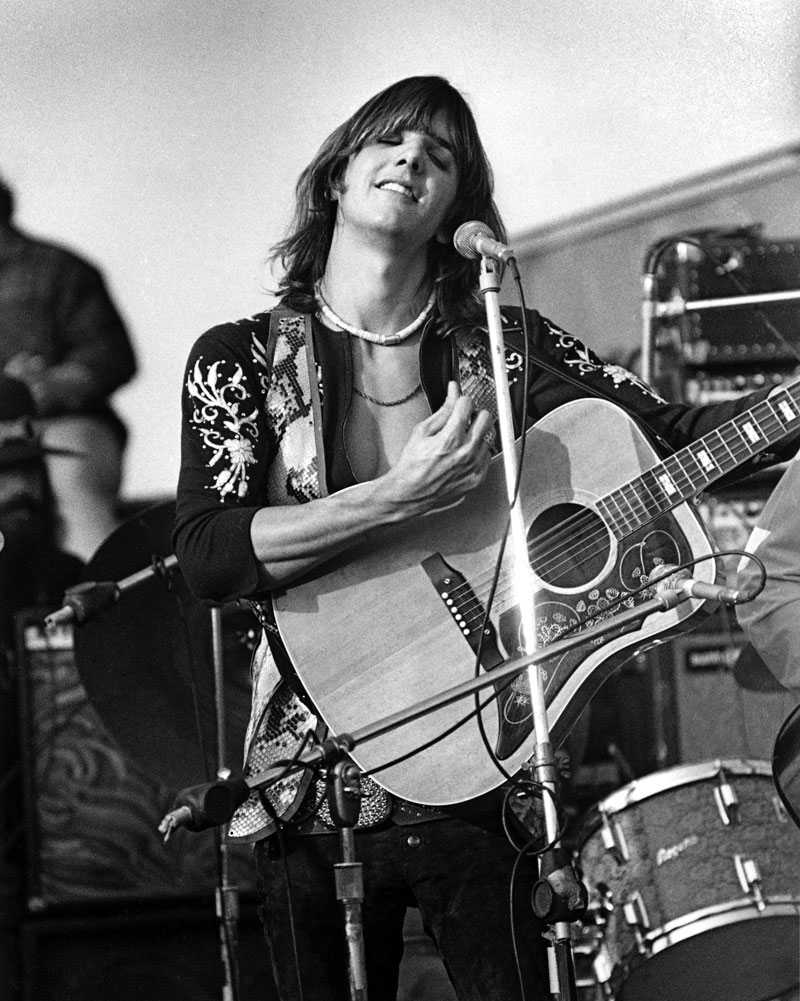

THE COSMIC COWBOY

Although Gamble Rogers is strongly associated with Winter Park, even among those who know little about his music, few realize that the genre-busting Gram Parsons was, for a brief time, a Winter Parker.

Most music fans remember the so-called Cosmic Cowboy best from his association with the Byrds in 1968, or from his short-but-historic collaboration with Country Music Hall-of-Famer-to-be Emmylou Harris.

In 2019, Ken Burns included segments on Gram and his influence on country music in two installments of his acclaimed PBS documentary series, Country Music.

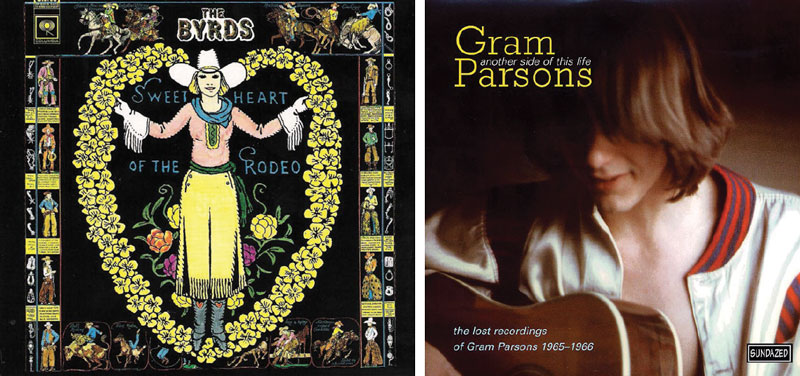

Gram’s two solo records: GP in 1972, and Grievous Angel in 1974, are considered five-star classics by Rolling Stone magazine. Neither were hits during his brief lifetime. However, his sound helped usher in the era of the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt and such Outlaw Country artists as Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings.

Although Gram is most associated with Winter Haven in Polk County — where his childhood home, Derry Down, has been converted into a performance venue — his family (at least the remnants of it) moved to a two-story home on Summerland Avenue on the shores of Lake Maitland in 1965.

Tragedy had always haunted Gram, then known as Ingram Cecil Conner III. His biological father, a World War II fighter pilot named Ingram Cecil Connor — known as “Coondog” for his sad eyes — had died by suicide two days before Christmas in 1958. Perhaps, it was speculated, he had suffered from PTSD.

Two years later, a suave New Orleans businessperson named Bob Parsons, a drinker and a dandy, wooed and married Gram’s widowed mother Avis (neé Snively) Conner, still only in her mid-thirties and a woman of significant wealth — a fact surely not lost on Bob.

Avis was the daughter of citrus magnate John A. Snively, a self-made man who by the 1930s owned the largest fruit packing and canning company in the nation. That made his heiress daughter quite a catch for a rounder who enjoyed living life in the fast lane.

Bob adopted Gram and his younger sister, also named Avis (mother and daughter were known as “Big Avis” and “Little Avis”). The couple also had a daughter together, Diane. Domestics, though, watched the children as the Parsons adults imbibed and partied.

But Big Avis, too, died young in 1965 — of cirrhosis of the liver — just prior to the decimated clan’s move. By the time Big Avis fell ill, Bob had begun an affair with the family’s young nanny — about Gram’s age — who moved along with Bob and his three children to their new home on Summerland. The two would later marry.

Bob’s philandering, it was whispered back in Winter Haven, had accelerated Big Avis’s alcohol abuse and contributed to her death. In that regard, a move to Winter Park — where the Parsons family drama was not known and therefore not gossiped about — made sense.

Gram, after flunking out of Winter Haven High School, had attended the prestigious Bolles School in Jacksonville, where he thrived on the institution’s structure and discipline.

By the time the family moved to Winter Park, Gram was a student at Harvard — where he claimed to have studied divinity but didn’t graduate — and stayed in a guest house on the property when visiting. Family money, perhaps, greased the skids at Harvard and helped to mitigate Gram’s checkered academic record.

Through all the tragedy involving his biological parents and the instability of his home life, Gram always had music as an escape and was very much drawn to folk music, then undergoing something of a revival among young people.

He kept a row of blue work shirts in his closet, the kind worn by Bob Dylan, according to childhood friend Jim Carlton, who would become a local musical icon and was part of the state’s burgeoning folk scene led by Will McLean and, of course, Gamble Rogers.

Carlton even recorded Gram when the young balladeer returned to Winter Park from Greenwich Village. There he was inspired and encouraged by such up-and-comers as John and Michelle Phillips — later of the legendary Mamas and the Papas — and Fred Neil, a Miami-based folkie who wrote the Midnight Cowboy anthem “Everybody’s Talkin’.”

Gram, says Carlton, had the looks, the talent and a trust-fund payout providing him with plenty of disposable income. “He wanted to be famous and groomed himself for celebrity,” adds Carlton, who now lives in Mount Dora. “With his magnetism, it was just in the cards.”

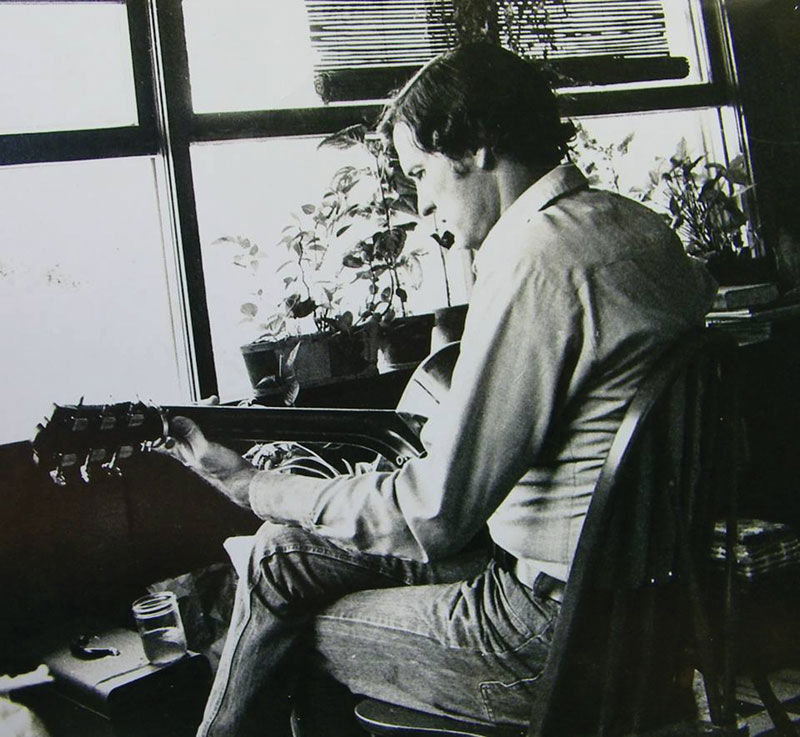

The setting for the recordings was informal. At Carlton’s home in Winter Haven, Gram would play the Gibson B-25 acoustic that Carlton had gotten as a gift from his parents, who liked their son’s friend but routinely expressed concern about his turbulent upbringing.

“It was a special instrument that really sang,” says Carlton, who played guitar in a band with fellow Winter Haven native Jim Stafford (“Spiders and Snakes”) and wrote jokes for Joan Rivers and the Smothers Brothers. “Still does, because most acoustic guitars improve with age.”

Carlton used a high-end reel-to-reel machine to capture Gram singing solo and strumming along to songs by his new friends Fred Neil and Buffy Sainte-Marie along with some of his own compositions, including “Brass Buttons,”written after his mother’s death:

Her words still dance inside my head,

Her comb still lies beside my bed.

But the sun comes up without her,

It doesn’t know she’s gone.

Understanding the potential significance of the sessions, Carlton squirreled away the recordings as a commemoration of his years-long friendship with Gram. He finally released them in 2000 as an album via Sundazed Records: Another Side of this Life: The Lost Recordings of Gram Parsons.

The rest is rock ‘n’ roll history. By 1966, the Parsons family had left Winter Park for New Orleans, and Gram had dropped out of Harvard and moved to California to chase his musical dreams. Within two years, he had landed a sideman gig with the Byrds alongside Roger McGuinn (now a Central Florida resident) and Chris Hillman.

In 1968, at Gram’s urging, inarguably one of the most important rock bands of the 1960s recorded their landmark crossover classic, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, at Columbia Studios in Nashville. Gram had become interested in country music while a student at Harvard, when he first heard Merle Haggard.

On March 15, 1968, Gram and the Byrds became the first rock band to play the Grand Ole Opry, much to the bafflement of the crowd that packed the Ryman Auditorium’s wooden benches and perhaps less so to the millions of others who listened in on transistor radios and couldn’t tell that they were listening to hippies.

In an audacious move, Gram took lead vocals. As planned, the Byrds opened with a Haggard cover, “Sing Me Back Home.” But for their second song, instead of another Haggard tune, the group unexpectedly offered an original, “Hickory Wind,” that Gram wrote and dedicated to his grandma.

What could have been more country than that? And the song, a wistful paean to a rural childhood, could hardly have been more down-to-earth if it had been written by Dolly Parton or Porter Waggoner.

In South Carolina,

There are many tall pines.

I remember the oak tree,

That we used to climb.

But now when I’m lonesome,

I always pretend,

That I’m gettin’ the feel,

Of hickory wind.

Yet Opry bigwigs, who broached no improvised setlists unless your name was Marty Robbins, were not amused. Although no recording of the performance exists, some claim the long-haired musicians exited the stage to boos and catcalls while others insist that audience response was polite but not effusive.

Undaunted by the chilly Opry reception, in 1969 Gram and Hillman — along with bassist Chris Ethridge and pedal steel player Pete Kleinow — formed the Flying Burrito Brothers and released The Gilded Palace, a groundbreaking album that combined modern country music with soul and psychedelic rock.

The album was a critical, if not a commercial, success. It did, however, continue to lay the groundwork for a genre of music that would become popular decades later. By 1971, due in no small part to Gram’s substance abuse and erratic behavior, the Flying Burrito Brothers had dissolved.

In 1973, Gram — who had recorded a solo album, GP, and recruited Emmylou Harris as a backup singer and duet partner for a newly formed touring band, Gram Parsons and the Fallen Angels — died of an overdose of drugs and alcohol in the Joshua Tree desert in California.

He was 26 at the time of his death, married (unhappily, by most accounts) to an aspiring actress named Gretchen Burrell and celebrating the completion of his second solo album, Grievous Angel.

Among the highlights of the groundbreaking compilation — which was released posthumously — are “Hickory Wind” and a spine-chilling cover of Boudleaux Bryant’s classic “Love Hurts,” with Harris singing high harmony.

Grievous Angel, which is today considered iconic, barely registered on the Billboard 200 in 1974. Gram didn’t live to see himself included on Rolling Stone’s “100 Greatest Artists” list, nor did he live to see the stellar career of his friend and collaborator, Harris, who would say that “I discovered my own voice singing in harmony with Gram.”

Stepfather Bob barely outlived his stepson. After years spent as the life of the party and abusing alcohol while playing the consummate chef and host, he succumbed to liver cancer in 1975, at age 50. Gram, though, ranks among the rock ‘n’ roll (and, arguably, country music) immortals.

Randy Noles is editor and publisher of Winter Park Magazine and has written two books about traditional American music. Bob Kealing is a historian, preservationist and author specializing in Florida-related pop culture. Among his published works are 2015’s Calling Me Home: Gram Parsons and the Roots of Country Rock and 2023’s Good Day Sunshine State: How the Beatles Rocked Florida (both from the University Press of Florida). Harold Fethe is a human resources executive and a jazz guitarist. Portions of the Gamble Rogers section of this story were originally written by Fethe and first appeared in Fretboard Magazine and later Winter Park Magazine.