My mother, Zhanna, and younger sister, Frina, both piano prodigies from Kharkiv, Ukraine, cheated death and survived the Holocaust by assuming false identities and spending the war entertaining Nazis who didn’t know they were Jewish.

I knew nothing of this until I was nearly 3o years old, when Mom broke her silence and revealed the broad outline of her astonishing story. But it would be another 15 years before she described in lacerating detail the emotional scars left by this horrific chapter of a long and otherwise happy life.

She divulged it all to our daughter, Aimée, then 13, who was interviewing her grandmother for a history assignment at Glenridge Middle School in 1994. Mom, quite unexpectedly, described how the Arshansky family was rounded up with 16,000 other Jews in Kharkiv, mocked and humiliated by the Nazis, kept in squalid conditions then put on a death march to a ravine called Drobitsky Yar.

She revealed how she miraculously eluded extermination, and how for the rest of the war she burned with anger as she played Chopin for audiences of soldiers who had murdered her parents and grandparents — and would certainly have murdered her, had she not slipped away after her father, using a gold watch, bribed a guard to look the other way. (Frina, who died in 2018, never told the story of how she, too, escaped.)

Why, I asked my mother, had she not told me and my brother her story? “How can you tell children about such things?” she replied. “It would have been too cruel.” As the decades passed, however, she decided that her real-life tale of terror should be — must be — passed along. And Aimée’s seemingly innocuous interview request provided an opening.

When the war ended in 1946, Zhanna, 19, and Frina, 17, were discovered in a displaced persons camp in Germany by a U.S. Army lieutenant and music lover, Larry Dawson, who heard them playing an old piano. The soldier pulled strings and called in favors to get them aboard the first ship of Holocaust survivors to arrive in America.

There, both sisters were awarded scholarships to the Juilliard School in New York City. Zhanna married the lieutenant’s brother — later my dad — a Juilliard-trained violist named David Dawson. Both had careers teaching and performing at the Indiana University School of Music. Frina, too, married a musician, pianist Ken Boldt, and worked as a performer, teacher and administrator at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

Yes, the story had a happy ending — as if the term “happy” could ever be used considering the horrific circumstances. Let’s just say the Arshansky sisters were more fortunate than millions of others.

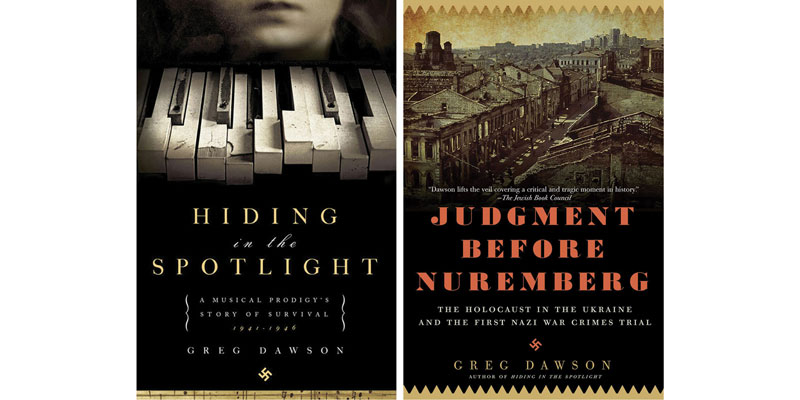

As you might expect, the revelations changed everything and sent me — along with my wife, Candy — on a journey to find out more. The result was Hiding in the Spotlight: A Musical Prodigy’s Story of Survival (Pegasus Books, 2009), which was written over the course of six years while I was working at the Orlando Sentinel as a consumer columnist.

When the book was published, Ukraine was, to say the least, far from top of mind for most Americans. I never could have imagined that only a dozen years later, Mom’s home country would become a household word and a fixture in our collective consciousness.

Coincidentally, before the Russian invasion, I was working on another book, Alias Anna: A True Story of Outwitting the Nazis, a reworking of the story for young readers that I co-authored with Susan Hood, a renowned writer of children’s books. Alias Anna was published in March by HarperCollins. (The sisters, concealing their Jewish heritage, performed as Anna and Marina Morozova, hence the new book’s title.)

By then the unimaginable had happened: History had repeated itself in a macabre reverse-mirror image, with a Russian leader doing to Ukraine what Hitler had done 80 years before. In 1941, terrified Ukrainians packed trains going east toward Siberia away from invading Germans. In 2022, they filled trains headed west toward Germany to escape Russian invaders.

Hitler was the greater mass murderer, killing an estimated 5 million Ukrainians — among them my grandparents and great-grandparents — but history will show that Russian President Vladimir Putin, in a fratricidal rage, wreaked far more devastation on the cities and villages and institutions of a place he considered part of his homeland.

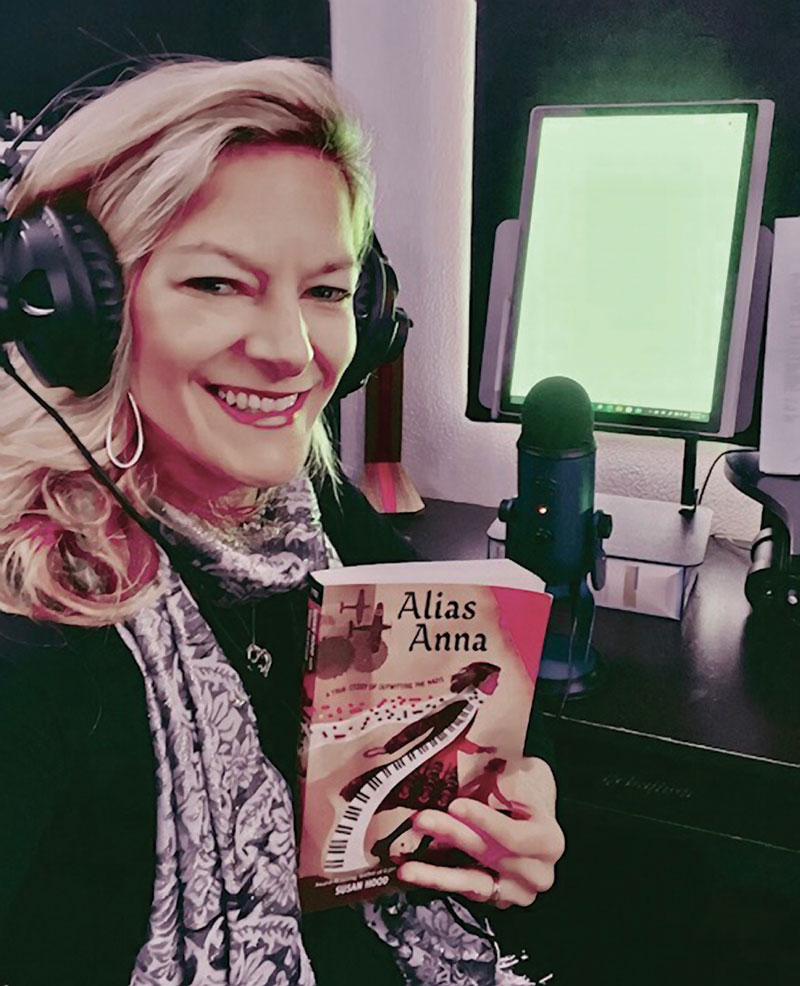

Zhanna’s story has become a family mission. Candy penned a screenplay optioned by filmmakers, a play produced in three states, and made a short documentary filmed in places now ravaged by Putin’s war, including Kyiv, Kharkiv and Mariupol. A quarter century after that fateful school assignment, history came full circle for Aimée when HarperCollins invited her to narrate the audio book of Alias Anna.

For Candy and me, the confluence of the war and publication of Alias Anna has compelled us to look for ways to support Ukrainians in their darkest hour, just as they helped my mother and Frina in theirs. More specifically, I’m referring to friends we made when we visited Ukraine in 2006 to research the first book to see the places that my mother had described.

Among their number are descendants of the Christian family that had sheltered the fleeing sisters at their own great peril; a middle-school teacher who for years has shared Zhanna’s story with her students (and, at press time, was still teaching despite the chaos of war); and a young scholar who served as our translator and is now a soldier on the front lines.

Finally, I’m thankful that my mother, now 95 and befogged by dementia, is not able to comprehend what is happening to her beloved homeland — this time at the hands of Russians. It would break her heart all over again.

What follows is my original afterword for Alias Anna — written before the invasion but edited and updated to reflect magazine editorial style and events of the war in Ukraine. Slava Ukraini! (Glory to Ukraine!)

I never had the experience of being a grandson. I never rode on my granddad’s shoulders or went downtown with him on Saturdays for ice cream. I never sat on my grandmother’s lap as she read Tom Sawyer aloud or helped me learn how to swim.

I never heard stories about where my mother’s parents grew up, what life was like when they were my age or what my mom and dad were like when they were kids. I knew my dad’s father had died young, and I only saw his mother once when she was quite ill.

All this seemed normal to me. The space filled by grandparents in most families was empty in mine — a vast desert devoid of family trees, stories, faces. It stretched to the horizon beyond my ken.

“Why didn’t you ever ask about your grandparents?” I was 60 years old when first asked the question. It came from someone in the audience at a Barnes & Noble where I was speaking about Hiding in the Spotlight: A Musical Prodigy’s Story of Survival, which had recently been released.

I had no answer for the baffled questioner and jokingly said that I was just a clueless kid interested in sports and TV cowboys. But I wondered, too, and the question keeps coming up about my mother’s parents.

Why didn’t I ask about them when I was growing up? Maybe because I didn’t even hear their names — Dmitri and Sara Arshansky — until I was pushing 30. That’s when my mother, for the first time, told me the basic outline of how they, along with her grandparents, were murdered by Germans at the edge of a ravine in Ukraine.

My children, Chris and younger sister Aimée, were blessed by rich relationships with grandparents: my wife Candy’s mother and father and his second wife, and my mother, Zhanna. They never knew my dad, their paternal grandfather, who died four months after Chris’s birth — a priceless connection short-circuited.

If not for my mother’s vivid presence in Aimée’s life, the remarkable story recounted in my book would have gone untold, buried like her parents and grandparents and countless others in the annals of Holocaust crimes.

Aimée was 13 when her history teacher at Glenridge Middle School asked students to interview a grandparent about what their life was like at the same age. Aimée, unaware of her grandmother’s story, turned to “Z” as she affectionately called her. We silently wished Aimée lots of luck in penetrating a fortress of silence.

Fifteen years earlier, when I was a columnist at my hometown newspaper in Bloomington, Indiana, NBC aired the groundbreaking miniseries Holocaust over four nights in April 1978. All I knew then was that my mother was a Russian refugee who came to America after the war.

Always desperate for material, I hoped she might have a few wartime memories that I could cobble together for a column to run during the miniseries. Gingerly, I asked her to share some memories. Grudgingly, she offered a small part of the story that she had kept from me and my brother.

The column ran, but my mother didn’t watch Holocaust and made it clear that she had no interest in ever again speaking about her life as a young girl in Ukraine. So when Aimée wrote her grandmother with an interview request, we didn’t hold our breath.

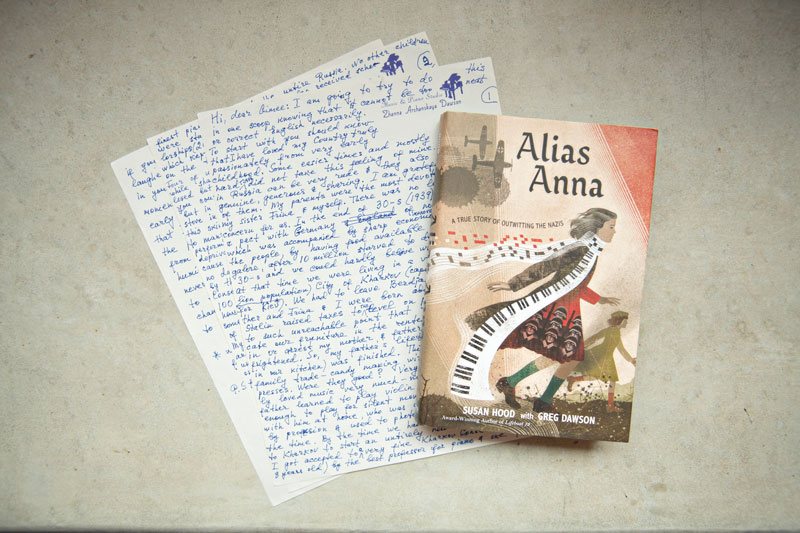

We had underestimated the mystic bond between grandchild and grandparent. Aimée’s “Dear Grandma Z” letter elicited a “Hi, Dear Aimée” reply — four handwritten pages on 8-by-10 stationery — in which my mother related her Holocaust experience in a deeper and more personal way than she had years earlier for my column.

Her words rang with love for her homeland, sorrow for her lost family, fury for the Nazis — “I can never tell anyone what hatred I had for them” — and a commitment to making her story “known to this world.” It was a long-delayed catharsis, an unlocking of memories, a second liberation — and her granddaughter had supplied the key.

Fired by a new mission, my mother agreed to be interviewed for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Project — a video archive of survivor testimonies — and sat down with me for many hours of conversation leading to the publication of two books, Hiding in the Spotlight and Judgment Before Nuremberg: The Holocaust in Ukraine and the First Nazi War Crimes Trial (Pegasus Books, 2012).

Books with artful covers, numbered pages and compressed narratives can give the false impression of history as an orderly beast. Like history and life itself, book research is disorderly — a long and crooked road with hard obstacles and sweet serendipity, dry wells and gold mines, despair and triumph.

At first, I thought I could tell my mother’s story using the interviews and material gleaned from the internet, such as the ship manifest for the U.S.S. Marine Flasher that brought her to America. But it turned out to be more complicated than that. The Nazis blew up Ukraine, scattering ashes to the winds. Imagine a crime scene with evidence — the dead, the buried, the missing — strewn across thousands of miles from America to Ukraine and Israel.

My first draft, which I hoped was the final one, recounted the amazing facts of my mother’s journey, but it didn’t feel amazing. It lacked passion, a sense of place. “You need to go to Ukraine,” Candy said. And she was right.

I had to walk the streets of Berdyansk on the Sea of Azov, my mother’s birthplace, where little Zhanna roamed the bazaars, sorted shells on the beach and joined funeral processions, bewitched by the mournful music.

I had to visit the grand music conservatory in Kharkiv, where she and her sister Frina studied, and stand at the door of the apartment where Nazis terrorized the family.

I had to see the barren field where the doomed Jews were kept for two weeks in a tractor factory with no heat, water or bathrooms in the dead of winter.

I had to walk their final walk — the exact route, on the same day, in the same arctic weather — to the killing field of Drobitsky Yar (recently desecrated by Russian bombs). And I had to see the spot where my mother jumped out of line into the woods, cheating Hitler.

In 2006, Candy and I visited Ukraine and Israel. Written after our return, my second draft was twice as long and much better than the first. I discovered the wisdom of the old saying that “eighty percent of success is showing up.”

Only because we showed up in Kharkiv was I able to visit the memorial at Drobitsky Yar and see Zhanna and Frina’s names mistakenly listed among those murdered there. Brushing my fingers across my mother’s name etched in Cyrillic on the marble wall was surreal and chilling, like reading my own epitaph — had the Nazis not let this particular girl get away.

Only because we showed up did we acquire one of the most remarkable photos in the books: A troupe of non-Jewish Ukrainian entertainers — singers, dancers, musicians — forced to perform for the invaders and to pose for propaganda purposes. All are staring straight at the camera except my mother, head turned in fear of being recognized as the famous Jewish prodigy from Kharkiv.

The photo was given to us by the woman who took it. She and her sister had worked with the troupe and read in a Jewish newspaper that we planned to visit the Kharkiv Holocaust Museum. We were stunned when they introduced themselves and presented us with the photo. They had been equally stunned to learn that the girls they knew as Anna and Marina were Jews in hiding.

Only because we traveled to Kharkiv could we visit the home of Zhanna’s classmate Nicolai Bogancha, whose Christian family risked death by sheltering the fugitive sisters for two weeks, helping them invent new names and a fresh life story before the girls departed on their long journey from persecution and fear to freedom. We broke bread with Nicolai’s widow in the same house, eating on the same beautiful plates the girls had used.

In May 1946, when Zhanna and Frina boarded the ship carrying some 800 Holocaust survivors on the voyage to America, all she brought with her from Ukraine was the sheet music for her beloved Fantasy Impromptu — five delicate pages that she had miraculously preserved through five years of war.

My father, David, died in 1975 at age 62, and by 2006, my mother was living and teaching in Atlanta. One day she picked up the phone and was taken aback when a woman speaking English with a heavy Russian accent said that her name was Tamara, a cousin.

Unlike the Arshankys, her family had taken an eastbound train to Siberia and survived the Nazi siege. Tamara said she was calling from Israel, where her family emigrated after the war, and that she had never given up trying to discover what had happened to Zhanna.

Mom didn’t believe her, suspecting an impostor, but Tamara finally made her believe, and sent the family photos used in my books. It was the first time I had seen pictures of my mother as a child and my first glimpse of the faces of my grandparents, Dmitri and Sara. When we visited Tamara in Israel, she gave us more photos expanding the picture of my mother’s life — and mine.

Nearly 80 years after the terror began, pieces of my mother’s fragmented story continued to appear — belated fruit of our research and publication of the books. In 2018, I received a Facebook message from a stranger named Ludmila who lived in Ukraine. She explained that her mother, Svetlana, a friend of Zhanna’s mentioned in the book, was still alive and lived in the same home in Kharkiv.

Before the Jews were sent to Drobitsky Yar, Zhanna had given Svetlana her blue silk concert dress for safekeeping. After escaping the death march, Zhanna returned to retrieve the dress and on the way out the door a matching scarf “dropped unnoticed and was left with me forever,” Svetlana said.

“Forever” ended in 2019. Svetlana’s granddaughter, Kate, who lives in Brooklyn, New York, with her Russian husband, Dmitriy, visited her mother in Kharkiv and returned with the priceless blue ribbon of silk cloth. The scarf and Fantasy Impromptu sheet music — the only remnants of the life Zhanna left behind — have become our most treasured possessions.

On our next visit, we handed my mother this lost piece of fabric, a symbol of her past. By then, at 92, dementia had stolen her voice, but her eyes told us that she knew what she was gently running through her still nimble fingers. She nodded and smiled with a faraway look. And I thought of the last thing she told me in our many hours of conversation.

“Somehow the story, the history, went around us instead of through us. It is a miraculous thing because anything could have been done to us at any moment in those five years. We did not remain the same, I assure you.”

Nor have we.

Editor’s Note: Greg Dawson, a former Orlando Sentinel columnist and a contributing writer to Winter Park Magazine, lives in Maitland with his wife, Candy. His books include Hiding in the Spotlight: A Musical Prodigy’s Story of Survival (Pegasus Books, 2009) and Judgment Before Nuremberg: The Holocaust in Ukraine and the First Nazi War Crimes Trial (Pegasus Books, 2012). A new book, Alias Anna: A True Story of Outwitting the Nazis (HarperCollins, 2022), is a reworking of Hiding in the Spotlight for young readers that he co-authored with Susan Hood, a renowned writer of children’s books.

UKRAINE BALLET BENEFIT ORIGINATES IN WINTER PARK

Marc McMurrin, president and CEO of the Winter Park-based Ginsburg Family Foundation, has pulled together an extraordinary benefit that will feature local arts groups performing with the National Ballet of Ukraine. All proceeds for the event will benefit humanitarian organizations working in Ukraine. The Ukraine Ballet Benefit will be Saturday, August 27, at Steinmetz Hall, the acoustic venue at Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts. Performing with the ballet, which was on tour in Western Europe when the Russian invasion began, will be the Orlando Philharmonic Orchestra and Opera Orlando. For more details on the benefit and how you can support it, visit our Events page.