Guntersville is a small (population 8,197) city in northeastern Alabama at the southernmost point of the Tennessee River, surrounded by 61,100-acre Lake Guntersville — the largest body of water in the state.

Its residents, like most Alabamians, are religious, politically conservative and forever defined by their degree of fealty to the football teams of either the University of Alabama or Auburn University.

It’s not the sort of place that you’d expect to produce many renowned visual artists, especially those whose thought-provoking works often depict the futility of war and pay horrifying homage to mystical mythologies of different cultures.

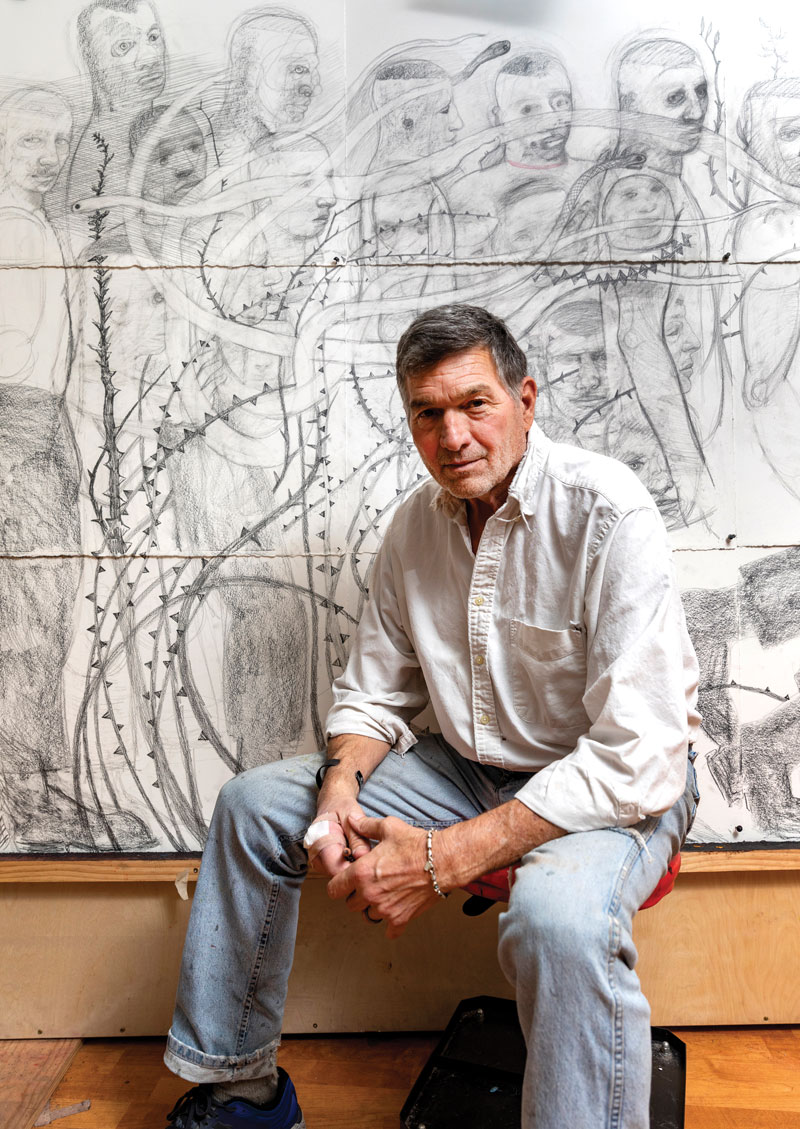

Guntersville did, however, produce Robert Rivers, 71, a University of Central Florida professor of art whose epic 286-panel cycle of mixed-media paintings, The Promised Land, last year won the Florida Prize in Contemporary Art. (There were just 231 panels, and only 69 on view, during the concurrent exhibition, which was held at the Orlando Museum of Art.)

“My father thought art was nothing that a man did,” recalls Rivers, who lives in Maitland and has taught at UCF since 1980. “Artists were sort of suspect. Football was a priority.”

In that regard, young Rivers didn’t disappoint — as a tackle and a linebacker at Guntersville High School, he competed for a 1967 state championship. He was inspired, he says, by Coach Bill Oliver, who had played defensive back for the legendary Bear Bryant at the University of Alabama.

“I thought maybe I wanted to be a football coach at the time,” says Rivers, whose refined twang would be instantly recognizable to fellow refugees of Sand Mountain, the sandstone plateau on which Guntersville is partially located. “I never thought I’d be an artist. But I drew all the time — mostly horses and football players.”

In fact, it was Rivers’s father — a former Marine fighter pilot in World War II — from whom he may have inherited his artistic talent. “My dad could draw beautifully,” says Rivers. But the family patriarch would have been sketching missiles and rockets, not tortured figures trapped in snake-infested hellscapes.

The elder Rivers was an aeronautical engineer, one of many skilled technical specialists who found homes along the shores of Lake Guntersville when they were hired to work for NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, located 37 miles to the northwest. Rivers recalls visits from Wernher von Braun, a neighbor and director of the space flight center.

Much about Rivers’s adolescence seemed idyllic. But much more of his time in Guntersville could have inspired a Pat Conroy novel. His father, he says, was a heavy drinker and often abusive. His mother, he says, was an even heavier drinker who could do little to control her husband’s volatility.

GOODBYE, GUNTERSVILLE

As soon as Rivers could get out of Guntersville, he did, enrolling at Auburn in 1969 and majoring in graphic design. “I sold it to my dad as becoming a commercial artist, which sounded more practical,” recalls Rivers, who found himself drawn to printmaking.

“Printmaking requires that you pare down and discard the nonessential,” says Rivers. “It helped me focus myself down into the little furrows I was making on the copper surface. I saw the significance of that etched line.”

Naturally the Vietnam War captured his attention, as it did most college-aged young people in the late 1960s. Rivers was horrified by the My Lai massacre, in which a company of American soldiers brutally killed most of the people — including children and the elderly — who lived in a small village.

As a result, he created a series of drawings inspired by the tragedy and found that his fellow students — especially in the more liberal confines of the art department — admired the work’s power.

Recalls Rivers: “I went from being this big dumb jock to being an artist who was taken seriously.” It marked the first time, but certainly not the last time, that he would return to dark themes that involved armed conflict, human suffering and man’s inhumanity to man.

Among his summer jobs during his Auburn years was an animal trainer at an attraction called Jungle Larry’s in Sandusky, Ohio. An animal lover, Rivers enjoyed caring for and training elephants and monkeys — and even performing with them in shows for tourists.

Although pursuing a career as an animal trainer crossed his mind, Rivers earned a BFA from Auburn in 1973 and started a decidedly more mundane workaday job as art coordinator at the Carpet and Rug Institute in Dalton, Georgia.

There he designed brochures, annual reports and trade show displays — and found rather quickly that he disliked commercial art. But the institute inadvertently kick-started his career as a fine artist by sending him to the Chicago Merchandise Mart, home to a gigantic annual furniture exhibition.

Rivers found little to interest him in the displays of tables, chairs, sofas and floor coverings. But a new world opened for him when he visited the Chicago Art Institute, one of the oldest and largest art museums in the world.

“That’s the first time I’d ever set foot in a real museum,” Rivers says. “It was the first time I’d ever seen a Goya painting, other than reproduced in books.”

Francisco Goya, a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker, is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. His paintings, drawings and engravings were often of asylums, riots, executions and bizarre animal-like creatures.

Rivers had always counted Goya among his greatest influences, but seeing his work in person was transformative. Upon his return to Dalton, Rivers says, his boss asked him to draw “two carpet fibers — one that’s happy because it’s clean and the other that’s sad because it’s dirty.”

That, Rivers recalls, was the final straw: “I applied to graduate school the next day.”

He earned a Ford Foundation scholarship to attend the School of Art at the University of Georgia in Athens, where he also played rugby. “I burned away any remaining commercialism in my art,” Rivers says. “I wanted to get as far away from that as possible.”

After earning an MFA in printmaking in 1977, Rivers became an assistant professor of art at the University of Wisconsin-Superior for two years until coming to the University of Central Florida — which had been Florida Technological University just the year before.

The Alabama-born artist’s creative output was impressive. He had already created a series called The Hospital Prints — jarring, Goyaesque black-and-while images inspired by his mother’s hospitalizations (she died in 1974 from cirrhosis of the liver).

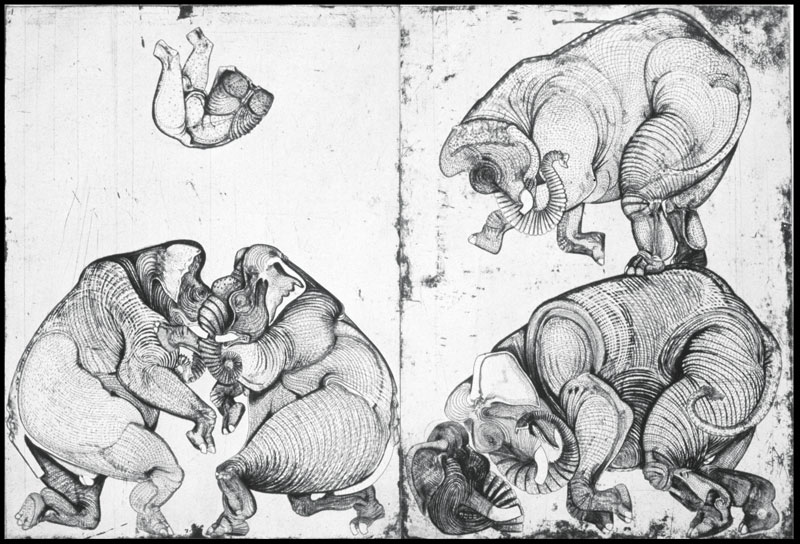

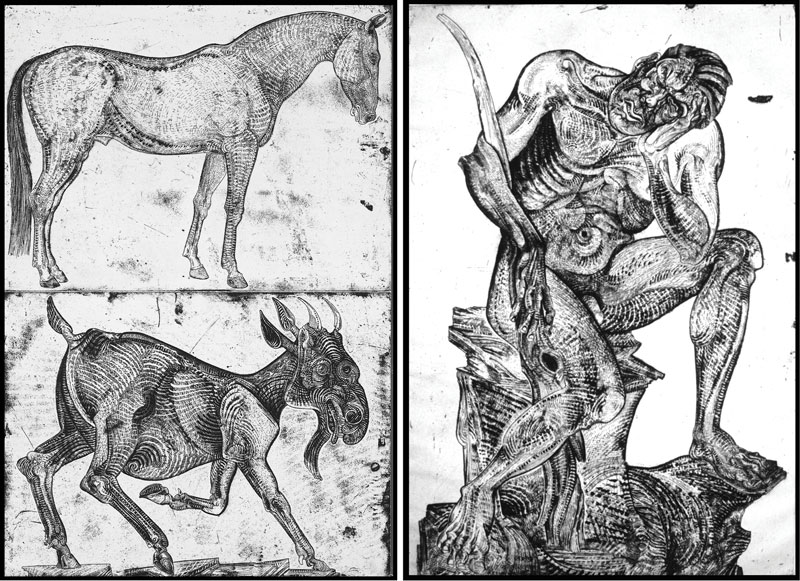

Rivers also began sculpting thickly glazed and textured ceramic heads — none of them boasting, shall we say, classically beautiful faces — and creating a series of copper-plate etchings featuring animals and figures from mythology called The War Prayer, based upon a 1905 essay of the same name by Mark Twain (see pages 28 and 29).

As it turned out, The War Prayer series — completed between 1984 and 2010 — thematically presaged The Promised Land. But well before that magnum opus got underway, explorations of tragic death had come to define Rivers’ work — and still does.

THE PROMISED LAND

Is Rivers, then, a prototypical tortured artist? If so, it’s hard to tell. Despite the grim nature of his subject matter, he’s genial and gregarious company — not what one might expect after perusing his portfolio. And he’s always up for an adventure.

In 1995, while on sabbatical from UCF, Rivers says he succumbed to “middle-aged craziness” and trampled across remote portions of South America. There he joined a perilous expedition along the 240-mile Biobío River, which originates in south-central Chile. He also scaled the mountains of Torres del Paine in Chilean Patagonia.

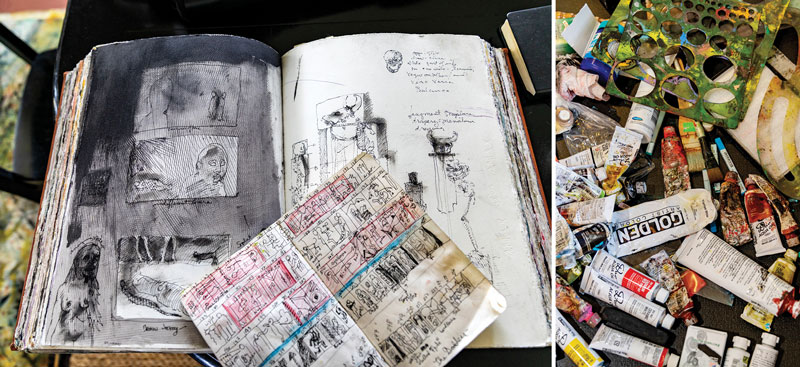

Rivers recorded his adventures in sketchbooks, which were bound by UCF’s Flying Horse Press into a series called The Handmade Books, several of which are now part of the permanent collections at, among other institutions, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Scottish National Gallery of Art in Edinburgh, where he had been a visiting lecturer and an exchange professor.

But his paramount achievement thus far — and certainly his most expansive — is The Promised Land series, which was inspired by the 2010 death of his nephew, Thomas, a service member in Afghanistan, from the blast of an improvised explosive device.

Rivers received the tragic news from his older brother, the soldier’s father, also named Thomas. “I didn’t fully comprehend what he meant at first,” Rivers says. “They’ve lost Thomas? Well, I asked, can’t they just find him? Then I realized that he had been killed. Operation Enduring Freedom, they called it. I painted my first panel that night.”

The first image in what would become an ongoing series was of a sleeping soldier with a snake coiled around his body.

The Promised Land, as described by Coralie Claeysen-Gleyzon, associate curator at the Orlando Museum of Art, “is at once overwhelmingly terrifying and astonishingly beautiful,” filled with ethereal wounded soldiers who journey through a barren underworld and encounter severed limbs, thorny plants, open graves and pits that may be portals to the afterlife — along with an odd assortment of mammals and reptiles.

Snakes are a continuing motif in The Promised Land, as well as in earlier works by Rivers, who traces the iconography to his upbringing on Sand Mountain. There, pockets of snake handlers still worship while dancing in the spirit and grasping writhing serpents, who sometimes lose their patience and inflict fatal bites on the faithful.

In fact, the TV news magazine Dateline NBC aired a report on northeast Alabama snake handlers in 2005. Recalls Rivers: “Steve Lotz [then chair of the UCF Art Department] saw it and said, ‘Well, Robert, that explains a lot of things about you.’”

The panels in The Promised Land — each more than 5 feet wide and nearly 3 feet tall — are rendered in graphite, red pencil, oil paint and washes made of tea and rust-colored acrylics that give the impression of dried blood.

Viewed individually or en masse, the symbolism in these panels can be interpreted many ways. But Rivers says that sometimes messages are discerned in his work that he doesn’t intend to convey.

Sometimes, though, he does. He certainly doesn’t dispute Robert Croker, one of his former professors at the University of Georgia, who says:

“[The Promised Land] is both a tribute to Thomas and a rumination of death in general, by violence in particular; the fragility and persistence of life; the uncertainty of an afterlife; the innocence of youth and the intensity with which our lives are bound to one another, regardless of the circumstance.”

Rivers does, however, dispute the notion that he harbors overarching political opinions about the 20-year war, which ended last August when President Joe Biden withdrew troops. About 2,500 American service members had died and about $2 trillion (mostly borrowed) dollars had been spent only to result in a rapid Taliban takeover.

“I definitely didn’t want to send a political message,” says Rivers — at least not about that specific war. “I just wonder why we keep sending our kids over into situations like that.” If gently pressed, he’ll go this far: “I think that once we got bin Laden, we should have gotten out of there.”

The Florida Prize in Contemporary Art, which comes with $20,000 in prize money, is awarded following an exhibition of works by the state’s 10 most progressive artists as determined by the museum’s jurors.

Last year, jurors included Aldeide Delgado, a Miami-based independent curator and founder/director of Women Photographers International Archive, and Aaron Levi Garvey, director and curator of Long Road Projects in Jacksonville and chief curator and program director of Jonah Bokaer Arts Foundation in Brooklyn, New York.

Rivers earned the nod from the judges, but the $2,500 People’s Choice Award, voted on during the Florida Prize Exhibition Preview Party, was won by Orlando painter Matthew Cornell.

“Winning the Florida Prize was one of the best nights of my life,” says Rivers. “A beautiful museum with beautiful people. It was a fantastic honor, and I was overwhelmed.”

Rivers was also overwhelmed by an unexpected appearance at the ceremonies by his brother, Thomas, whose son is memorialized in The Promised Land. “I didn’t know he was that good,” commented Thomas after viewing his brother’s display.

Rivers’s art has been displayed all over the world, and selected collections are housed in the National Gallery of Art and the Corcoran Gallery, both located in Washington, D.C. His work can also be found in the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Montgomery, Alabama, and the Gallery of Art in Edinburgh, Scotland.

These days, Rivers continues to teach — he was relieved to have mastered the technology required to teach remotely, which is hardly ideal for art instruction — and continues to turn out Promised Land panels from his spacious second-floor garage studio attached to his home in Maitland.

Rivers, who rekindled a lifelong love for horses, began riding jumpers in 1997. Through his interest in horses, he met Peggy Stevens and the pair married in 2008. Together, they operate Brookmore Farms, a horse boarding and training facility in the Lake Howell area of unincorporated Winter Park.

In fact, at press time he was recovering from a near-disastrous accident in which the horse he was riding fell on him and broke his collarbone, then trampled his hand with its hoof. Luckily, none of the small bones were broken.

Just as important to Rivers, though, the horse was uninjured. “As for me,” he says, “I just forced myself to paint with my left hand for a while.”

‘BLAST THEIR HOPES, BLIGHT THEIR LIVES’

The War Prayer series was inspired by a controversial Mark Twain story.

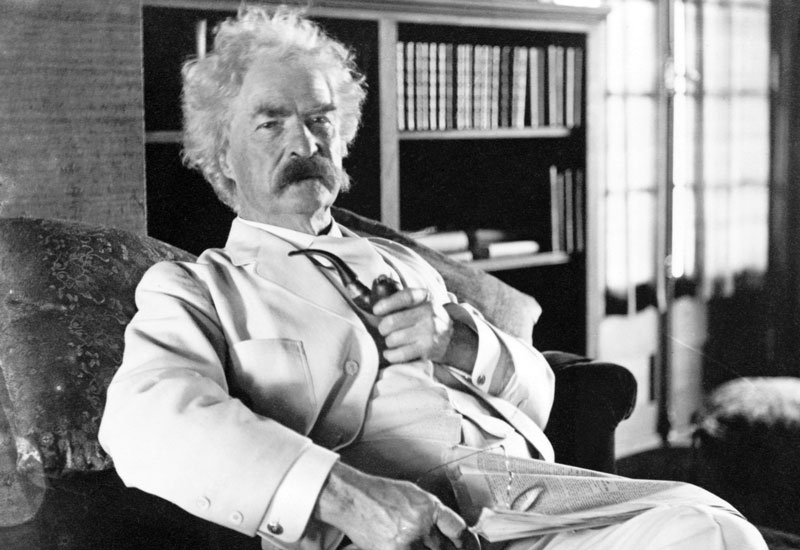

One of Robert Rivers’s most powerful series of prints was inspired by The War Prayer, a short story (or prose poem) written by Mark Twain in 1905 but not published until 1916, six years after the iconic and irascible writer’s death.

Twain, who usually thought nothing about speaking his mind regardless of who might take offense, knew that this scathing indictment of blind patriotic and religious fervor would stir up a career-damaging frenzy. So he chose not to publish it in his lifetime.

“I have told the whole truth in [The War Prayer],” Twain told a friend. “Only dead men can tell the truth in this world. It can be published after I am dead.”

The story’s premise: An unnamed country goes to war — perhaps, it has been speculated, the Spanish-American War — and dutiful citizens attend a church service to call upon God to grant them victory and protect their troops.

Suddenly, an “aged stranger” appears and announces that he is God’s messenger. He tells the congregation that he has been sent to speak aloud the second (but unspoken) part of their prayer — the part that wishes suffering and destruction on the enemy.

What follows is a gruesome description of the horrors of war, spoken in the pious language of a preacher beseeching the Almighty. Writes Twain, upon the prayer’s conclusion: “It was believed afterward that the man was a lunatic, because there was no sense in what he said.”

Rivers first heard The War Prayer on PBS in 1981, when it was dramatized in The Private History of a Campaign That Failed, a fictionalized account of Twain’s brief stint as a Confederate soldier. The prayer was spoken by actor Edward Herrmann.

“I was just blown away by the language,” says Rivers. “I went to the library to find a copy. I used some of the lines from the poem as titles for my prints. The sentiments really spoke to me.”

The War Prayer was first published in Harper’s Magazine — as World War I raged — and remains in print today, as relevant as ever. It is considered to be one of the most powerful antiwar commentaries ever written and presages Rivers’s Promised Land series.

THE WAR PRAYER

Lord our Father, our young patriots, idols of our hearts, go forth into battle — be Thou near them! With them, in spirit, we also go forth from the sweet peace of our beloved firesides to smite the foe. O Lord our God, help us tear their soldiers to bloody shreds with our shells; help us to cover their smiling fields with the pale forms of their patriot dead; help us to drown the thunder of the guns with the shrieks of their wounded, writhing in pain; help us to lay waste their humble homes with a hurricane of fire; help us to wring the hearts of their unoffending widows with unavailing grief; help us to turn them out roofless with their little children to wander unfriended in the wastes of their desolated land in rags and hunger and thirst, sports of the sun flames of summer and the icy winds of winter, broken in spirit, worn with travail, imploring thee for the refuge of the grave and denied it. For our sakes who adore Thee, Lord, blast their hopes, blight their lives, protract their bitter pilgrimage, make heavy their steps, water their way with their tears, stain the white snow with the blood of their wounded feet! We ask it, in the spirit of love, of Him Who is the Source of Love, and Who is the ever-faithful refuge and friend of all that are sore beset and seek His aid with humble and contrite hearts. Amen.