In the classic 1951 science fiction film The Day the Earth Stood Still, a humanoid from another world, Klaatu (Michael Rennie), lands his flying saucer on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., causing worldwide alarm.

Exiting the saucer, Klaatu announces that he has “come in peace and good will,” but is shot and wounded by an overeager soldier. A hulking robot called Gort then appears and turns several military vehicles to ash using a mysterious ray blast emanating from behind a visor-like opening.

A wounded Klaatu later explains that the inhabitants of other

planets have become concerned by the existential threat now posed by the Earth, particularly since pugnacious humans have developed rockets and rudimentary atomic power.

The planet will be “eliminated,” Klaatu warns, unless the people unite and agree to end war. Over the course of 90 minutes or so, earthlings do everything possible to confirm the interstellar emissary’s impression of them as hopelessly warlike.

As Klaatu takes his leave, having failed to unite the world’s political leaders (and getting shot yet again for his trouble), the erudite alien issues a stark warning to a multicultural gaggle of scientists and sympathizers assembled around the saucer.

He explains that other civilizations throughout the galaxy have managed to live in harmony because an interplanetary organization has created a police force of invincible robots like Gort, whose sole purpose is to destroy those who attack other planets — with no questions asked.

Not surprisingly under such an irrevocable arrangement, there would be considerable incentive to negotiate peaceful settlements when disputes between planets threatened to boil over.

“In matters of aggression, we have given [the robots] absolute power over us,” Klaatu concludes. “Your choice is simple: join us and live in peace or pursue your present course and face obliteration. We shall be waiting for your answer.”

So, what is the relationship between the premise of this Cold War-era morality tale — today considered by The New York Times as one of the “1,000 Best Movies Ever Made” — and Rollins College President Hamilton Holt, who led the institution from 1925 to 1949?

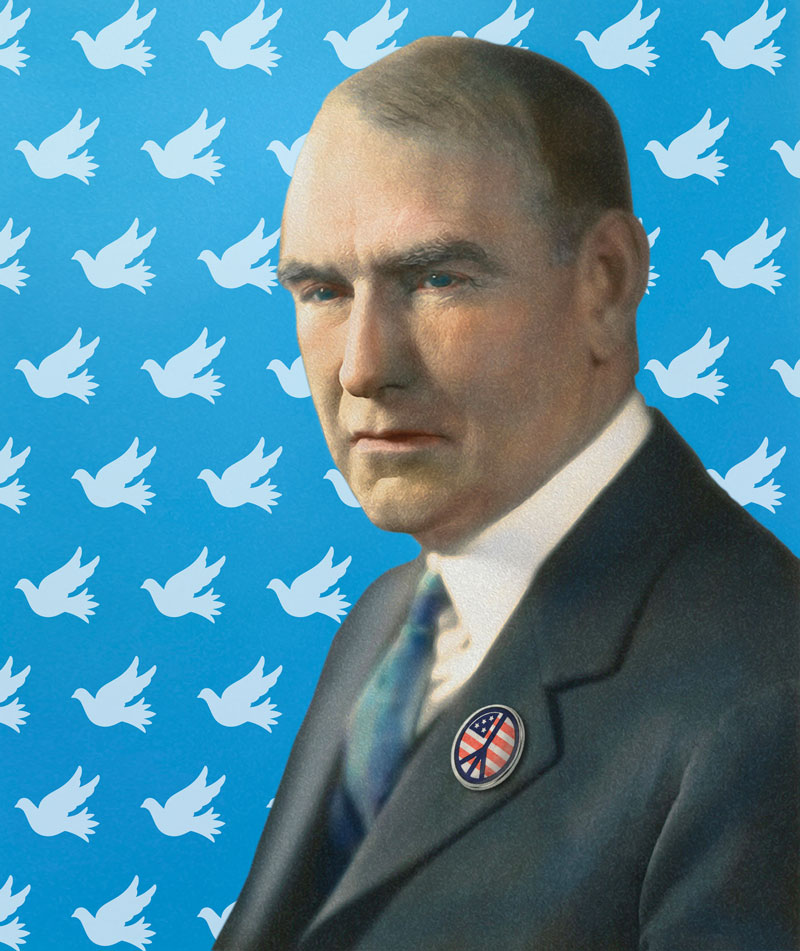

For decades, Holt had been preaching about peace through world government. Although he is best remembered today for his classroom innovations and educational reforms, his true passion was to see all nations confederated under one authority that would arbitrate disputes and keep the peace.

That sounds relatively benign, although entirely unrealistic. However, although Holt certainly did not envision deploying an army of invincible robots to compel good behavior, he did envision a legally constituted international entity that could use force against aggressor states.

Yes, Holt agreed, individual countries could maintain small armies. But the so called world government — a kind of United Nations on steroids — would command an army larger than any single country or alliance of countries.

The idea that every nation on the planet — particularly superpowers and bitter regional enemies whose hatreds can be traced to ancient times — would agree to this sort of subjugation seems naïve at best.

But what appears today to be a crackpot theory was, at times, considered at least worth discussing among academics and intellectuals like Holt. Milder versions (sans the international army) were even given lip service by some prominent politicians, including several presidents.

The United States, it was argued, was founded as 13 colonies bound together by the Articles of Confederation. The nations of the world, then, ought to be ready and willing to implement “a new order of civilization” based upon the Founding Fathers’ vision for America.

Suffice it to say, one need not be a professor of international affairs to understand why world government was always a nonstarter. Holt, however, was a leader in this quixotic movement. And he never wavered in his belief that it was “the manifest destiny” of the United States to unite the all nations in “a Declaration of Interdependence.”

He gave essentially the same world government speech perhaps thousands of times between 1910 and 1950, and seemed legitimately convinced that reasonable people, regardless of their country of origin or their political and cultural differences, would eventually see the logic and come around.

Holt, whose heart was surely in the right place, died believing this — which says more about the man and his unflinching optimism than about the Utopian idea that he championed.

An Opinionated Editor

Hamilton Holt was never reticent about expressing opinions. As the owner/editor of an influential weekly opinion journal prior to his 24-year stint as president of a college in out-of-the-way Winter Park, Holt was a public intellectual whose high-profile crusades for social justice and world peace helped shape the national discourse preceding and following World War I.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1872, Holt was the son of George Chandler Holt — a district court judge in the Southern District of New York — and Mary Louise Bowen Holt. Later his family moved to Spuyten Duyvil in The Bronx, where he spent his childhood.

Holt, an 1894 graduate of Yale University with a degree in economics, was an undistinguished student who despised the classical curriculum and mind-numbing lecture-and-recitation pedagogy that he had endured in college. Surely, he thought, there was a better way.

While studying sociology at the Columbia University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Holt worked part-time at the family-owned magazine, co-founded in 1848 by his maternal grandfather, Henry C. Bowen.

Originally a pro-abolitionist religious journal, The Independent had evolved to encompass content intended for sophisticated and politically progressive readers. In 1897, Holt abandoned his pursuit of a doctoral degree to focus on his new role as managing editor of the weekly.

He solicited manuscripts, edited copy and wrote editorials and features, perhaps most notably a series of 75 “lifelets” — a memorable moniker for compact but compelling autobiographical sketches of “the humbler classes” representing various races and ethnicities.

He collected 16 lifelets for a 1906 book, The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans: As Told by Themselves, which he described hopefully in the introduction as having “perhaps some sociological importance.”

At The Independent, Holt came to believe that a lively, collaborative workplace was more intellectually stimulating, and more conducive to learning, than a stuffy classroom in which a professor pontificated while students struggled not to snooze.

In 1912, Holt formed the Independent Weekly Corporation and bought The Independent outright from his uncle, Clarence W. Bowen, for $44,000, most of which was borrowed from friends.

In the coming years, Holt and a rotating roster of notable contributors championed such causes as civil rights, organized labor, open government, universal suffrage and prison reform.

“The average reader has no conception how much hard thinking and painstaking experiment is given in every up-to-date magazine to the headlines, titles, sub-titles, borders, tail pieces, etc., before the desired effect is precisely secured,” said the meticulous Holt.

He also pursued aggressive growth strategies. Between 1912 and 1917, The Independent absorbed three other magazines — The Chautauquan, Harper’s Weekly and Countryside — pushing circulation to more than 125,000.

However, to the detriment of thoughtful mass-market journalism, such contemplative (if wordy) weeklies began to disappear in the early 1920s, when a sharp economic downturn pummeled the advertising market and the public clamored for lighter fare such as The Saturday Evening Post and The Ladies Home Journal.

“Peace has at last become a practical political issue — soon the political issue before all the nations. It seems destined that America should lead in this movement. The United States is the world in miniature. The United States is a demonstration that all the peoples of the world can live in peace.”

—An excerpt from Hamilton Holt’s stump speech on world government

The peripatetic Holt — likely to the detriment of The Independent, which might have lasted longer with his undivided attention — expended more time and energy as a peace activist.

He barnstormed the country from 1907 to 1914 delivering his “Federation of the World” lecture under the auspices of the Peace Society of New York, the World Peace Foundation and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“Now, my friends, the peace movement is no longer a little cult of cranks,” said Holt in a typical stump speech, which was usually illustrated by stereopticon images of the 1907 Hague Convention in the Netherlands, which was attended by delegations from more than 100 countries including the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany Russia, China and Persia (today Iran).

Holt, who covered the conference for The Independent, believed that the international Permanent Court of Arbitration established there was a step in the right direction but ultimately inadequate because it lacked the authority to enforce its rulings.

“Peace has at last become a practical political issue — soon the political issue before all the nations,” he declared. “It seems destined that America should lead in this movement. The United States is the world in miniature. The United States is a demonstration that all the peoples of the world can live in peace.”

Then came the presentation’s final flourish: “And when that golden period is at hand — and it cannot be very far distant — we shall have in very truth Tennyson’s dream of the parliament of man, the federation of the world, and for the first time since the Prince of Peace died on Calvary, we shall have peace on earth and good will to men!”

The title of Holt’s lecture was a line from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s 1843 poem “Locksley Hall.” The relevant portion reads: “Till the war drum throbbed no longer, and the battle flags were furled / In the Parliament of man, the Federation of the world. / There the common sense of most shall hold a fretful realm in awe / And the kindly earth shall slumber, lapt in universal law.” (The most famous line from “Locksley Hall” is: “In the spring a young man’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love.”)

In 1910, Holt chaired the World-Federation League and testified before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs. He and other members supported a league-authored resolution introduced by Representative Richard Bartholdt of Missouri.

This resolution called upon President William Howard Taft to appoint a commission that would draft “articles of federation” for the “maintenance of peace, through the establishment of a court that could decide any dispute between nations.”

The commission would consider “the expediency of utilizing existing international agencies for the purpose of limiting armaments of the nations of the world by international agreement, and of constituting the combined navies of the world [into] an international force for the preservation of universal peace, and to consider and report upon any other means to diminish the expenditures of government for military purposes and to lessen the possibilities of war.”

Unlike The Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration, the more powerful body could “enforce execution of its decrees by the arms of the federation, such arms to be provided to the federation and controlled by it.”

Wary of the policing provision, both houses of Congress instead unanimously passed a far less ambitious joint resolution that called for a commission to investigate both arms reduction and the creation of a multinational naval force to patrol the sea.

Holt, tenacious but never one to take an all-or-nothing position, thought that the diluted resolution was at least a step in the right direction and personally asked former President Theodore Roosevelt — who had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906 for negotiating an end to the Russo-Japanese War — to serve as the commission’s chairman.

“It is said to be extremely likely that before many months have passed, a powerful peace commission will be in existence with the Colonel at its head,” predicted one widely circulated editorial.

Roosevelt, however, demurred, telling Holt that no U.S. president should pioneer an international movement. “Let others sow the seed,” said the Rough Rider, according to later accounts from Holt. “But let [the president] reap the harvest.”

Holt may have been puzzled by the response, particularly considering Roosevelt’s supportive public declarations. In his 1904 address to Congress, Roosevelt had announced a “corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine vowing that the United States would act as an international police force to bar foreign intervention in Latin America.

More recently he had gone even further. During a belated 1910 Nobel lecture in Oslo, Norway, he had called for treaties of arbitration between nations as well as “a league of peace, not only to keep the peace among [league members], but to prevent, by force if necessary, its being broken by others.”

In any case, Taft, whose diplomats floated the idea and received discouraging feedback from their counterparts, let the matter of a commission drop for the time being.

A (Not So) Practical Proposal

At the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, Holt revisited the topic of world government in “The Way to Disarm: A Practical Proposal.” The editorial, which appeared in The Independent and other publications in September of that year, contained little that was new but was widely praised.

“That the world should go on after the appalling experiences it is now undergoing … is a prospect to which no thinking mind can reconcile itself,” wrote the New York Post.

The editorial continued: “When the bloodshed and devastation come to an end, the best thought in every nation must be centered upon the possibilities of remedy. And it is not improbable that it will be along such lines as those indicated by Mr. Holt that the remedy will be sought.”

Encouraged, Holt marshaled his resources. The League to Enforce Peace, again subsidized by Carnegie’s foundation, was formed in 1915 by Holt and Theodore Marburg, a long-time activist in international peace movements and a previous U.S. minister to Belgium.

Now-former President Taft, again at Holt’s behest, agreed to chair the new organization. Executive committee members included Holt as well as Abbott Lawrence Lowell, president of Harvard University, and Oscar S. Straus, former secretary of commerce and labor under Roosevelt.

Charter members also included another Roosevelt administration alumnus, Elihu Root, former secretary of state; as well as Alexander Graham Bell, scientist and inventor; Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, progressive social activist; Cardinal James Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore; and Edward A. Filene, a department store magnate representing the newly formed United States Chamber of Commerce.

In June of that year, at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, league members endorsed a federation of nations whose members would “jointly use their economic and military force against any one of their number that goes to war or commits acts of hostility against another.”

Just weeks prior to the meeting, German submarines had sunk the British ocean liner Lusitania. The Kaiser, league members agreed, must be held to account; war, they assumed, was inevitable. The issue for Holt and others was how the world would be structured in the war’s aftermath. Once Germany was subdued, perhaps their ideas could gain real traction.

With a new sense of urgency, Holt again crisscrossed the country with a world government lecture that covered familiar territory but seemed more relevant in light of world events. Since antiquity, he told audiences, cities and states had resolved their differences with one another through legal means. Could nations not do the same?

Said Holt: “The peace problem, then, is nothing but the problem of finding ways and means of doing between the nations what has already been done within the nations.”

World government advocates were not, he was careful to explain, intractable pacifists who demanded that all nations lay down their arms immediately. Nor did they propose that nations give up their operational autonomy.

Because smaller individual armies would be permitted, “the league therefore reconciles the demand of pacifists for the limitation of armaments and eventual disarmament, and the demand of militarists for the protection that armament affords.”

Still, because international police power remained a delicate issue, Holt vowed that any world governing body would exhaust every option before resorting to force against recalcitrant federation members.

In the meantime, Germany continued its program of unrestricted submarine attacks against all ships that entered the war zone around the British Isles. In addition, it was revealed that the German government had sought a military alliance with Mexico to recapture Texas, Arizona and New Mexico.

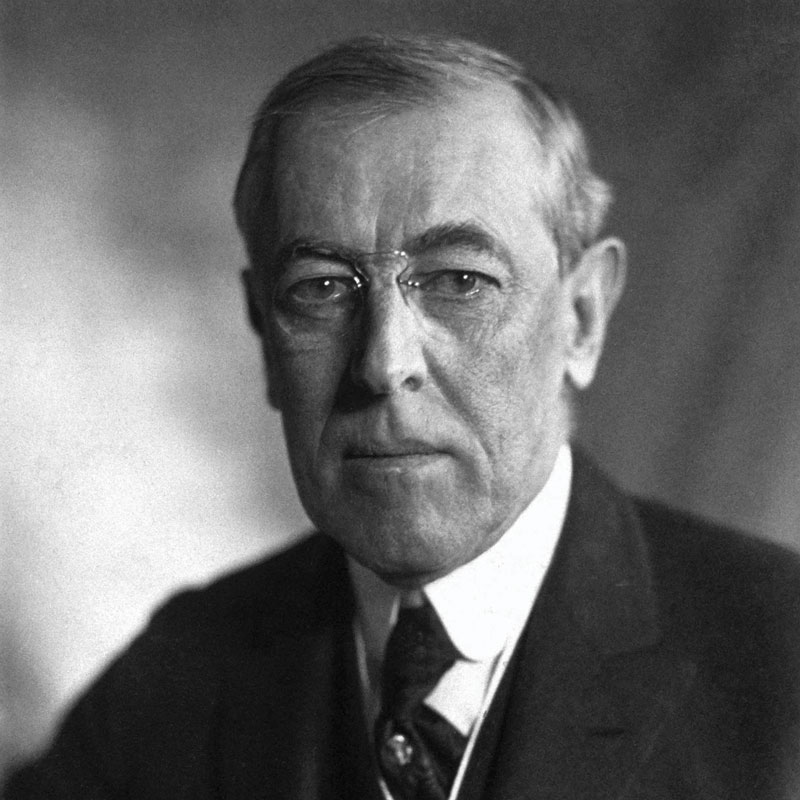

On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson, who had been reelected the prior year in part by maintaining neutrality, appeared before the U.S. Congress and called for a declaration of war “against human greed and folly, against Germany, and for justice, peace and civilization.”

The league wholeheartedly supported the Allied effort to stamp out German militarism — it was, after all, a league to enforce peace, not just to wish for it — and distributed hundreds of thousands of pieces of pro-war literature. It also established a National Speakers Bureau through which some 3.8 million people were reached, according to league estimates.

In the spring and early summer of 1918, Holt spent three months in Europe, sending surprisingly jingoistic dispatches from the front lines to The Independent.

“The way our soldiers and sailors and marines have waded into the big fight and made good has electrified England and the continent,” he told the New York Sun upon his return.

Holt added: “I don’t think it is too much say that the people in France, Italy and the other countries I visited look up to President Wilson as much or more than their own great leaders. They have come to revere him as their savior.”

No ‘Mongrel Banners’

When the war ended with the signing of the Armistice in November 1918, concepts put forth in “The Way to Disarm” and supported by the League to Enforce Peace informed much of Wilson’s thinking.

In early 1919, Holt and Straus traveled to the Paris as observers when Wilson (who was ill and erratic, perhaps the result of a stroke) negotiated and signed the Treaty of Versailles. Granted, the resulting League of Nations was considerably less potent than a world government that could by law — or, if necessary, by force — act to maintain order and guarantee security.

But Holt and his allies rallied around the organization, reasoning that it was at least a start and could later be strengthened.

“The dreams of the poets, prophets and philosophers have at last come true,” Holt wrote in a dispatch from Paris published in The Independent. “There can be no doubt whatever about it. The peace conference itself is the germ from which a real united nations will eventually develop.”

Holt, a lifelong Republican, became an enthusiastic Wilsonite — although he did not yet change his party affiliation. In 1920, he was named the first executive director of the endowment fund for the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, an educational nonprofit established to make cash awards to individuals and groups that advanced world peace.

Chairman of the National Committee of the Wilson Foundation was former Assistant Secretary of the Navy and future President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who proved to be a surprisingly ineffective fundraiser.

Still, donors received a certificate imprinted with Wilson’s words from his 1917 address to Congress seeking a declaration of war: “The world must be made safe for democracy. Peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty.”

Holt also became involved in various international friendship societies, including the Italy America Society, the Netherlands America Foundation, the Friends of Poland Society, the American-Scandinavian Foundation and the Greek American Club.

In Holt’s view, the world would inevitably become “federated in a brotherhood of universal peace” even if progress toward that noble goal was incremental.

Then, despite Wilson’s exhausting effort, the U.S. Senate failed to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. At issue was Article 10 of the League of Nations covenant, which regarded collective security.

“I have loved but one flag and I cannot share that devotion and give affection to the mongrel banner invented for a league,” thundered Massachusetts Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, an opposition leader who contended that the article violated U.S. sovereignty and could lead to unwanted military entanglements.

Holt, though, was unwilling to capitulate; in 1922, he organized the League of Nations Non-Partisan Association and through it attempted to rally public opinion and exert political pressure.

After disassociating himself from The Independent’s successor publication, which ambiguously declared that its purpose was to “promote the principles of liberal conservatism,” Holt continued to participate in internationalist organizations.

In 1924, after anti-league Republican Warren G. Harding won the presidential election, he bolted the party for good and ran as a Democrat for a vacant U.S. Senate seat in Connecticut, where he had registered to vote just months before. (His summer residence was his mother’s family homestead in Woodstock, a picturesque village in the northeastern corner of the state.)

Holt discovered, however, that League of Nations membership was not a compelling enough issue to overcome the statewide strategic advantage enjoyed by Republicans.

The Hartford Courant, in endorsing his Republican opponent, Hiram Bingham, contended that Holt’s world government crusade had hindered preparedness and cost lives when the United States entered World War I.

“We would not say that Mr. Holt knew that would be the result when he opposed preparedness,” wrote the Courant. “But he is properly chargeable with bad judgment … and we want no bad judgment in the handling of the votes of the state of Connecticut in the United States Senate.”

The editorial went on to call Holt “a pronounced pacifist” — which was not strictly true, since he had supported the war effort. In contrast, Bingham, was described as “gallant and soldierly.”

Holt lost the race in a rout and was back on the lecture circuit when he received a fateful letter from Rollins College in Winter Park.

Small Town, Big Ideas

A proverbial citizen of the world, Holt was not intimidated dealing with representatives from a shaky provincial college that surely needed him more than he needed it.

Although he had never run a college — he did not, in fact, hold an advanced degree — he had opined frequently about higher education’s perceived shortcomings.

Colleges were infected with three major ills, Holt wrote: “First, the insatiable impulse to expand materially; second, the glorification of research at the expense of teaching; and third, the lack of human contact between teacher and student.”

Holt was no stranger to Rollins or to Winter Park. He first visited the campus in 1910 to deliver his perennial “Federation of the World” lecture.

There is no mention of the address in The Sandspur, the student newspaper, but it was likely well received on campus (assuming the audience consisted of young idealists), and Holt was a guest of honor at a reception hosted by President William F. Blackman.

In 1914, Blackman invited Holt to join the college’s board of trustees, on which he served a single two-year term, resigning when it became apparent that he was too preoccupied trying to save mankind (not a hyperbolic statement in Holt’s case) to meaningfully participate.

In 1924, Holt returned to Rollins during another lecture tour and informally discussed the now-vacant presidency. (Robert James Sprague, a college dean, was serving as acting president.) But the position was offered instead to William Clarence Weir, formerly president of Pacific College in Forest Grove, Oregon.

(Weir mysteriously retired due to unspecified health reasons a year later. But whatever ailed him didn’t linger. A few months following his departure from the college, according to city directories, Weir and his wife, Nettie, were operating The Weir System, a real estate office, in Orlando.)

Bestselling novelist Irving Bacheller, a college trustee, then wrote Holt to gauge his interest in the position. He suggested a salary of $5,000 per year (the equivalent of about $70,000 today), noting that the job would be “a cinch for a man of your capacity.”

The timing was fortuitous for Holt; his recession-battered magazine had been absorbed in 1921 by The Weekly Review, a competitive publication, leaving Holt with $33,000 in personal debt.

In addition to having no steady source of income, Holt was beset by concerns that he had for years neglected his health and his family, which consisted of his wife, Alexandria Crawford Smith, and their four children: Beatrice, Leila, John Eliot and George Chandler.

For these and other reasons, Holt was eager to settle in Florida — a place he believed offered boundless opportunity — and was intrigued by the challenge of testing his theories about higher education. But he was accustomed to earning at least twice as much, even if the checks were less steady.

“I could not accept the terms you offer as I am unwilling to have any permanent connection with any educational institution that is compelled to underpay its president or professors,” he replied, countering at $10,000 per year. Both parties, he added, could reevaluate after the winter term.

In fact, some trustees speculated that Holt was “too big a man” to be truly interested in becoming a small-town college administrator, with its attendant paper-pushing and glad-handing.

But perhaps out of regard for Bacheller’s judgment — and when a less expensive but arguably more qualified candidate declined — the college hired Holt in October 1925.

Congratulatory messages from notables in politics and academia poured into the college, including one from now-U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Taft that read: “[Holt] is a man of the highest probity and character, a man of wide experience and great ability. I felicitate the college on securing him.”

On that mannerly note, the Holt Era began.

“When I became president of Rollins College my viewpoint, naturally, was that of a layman,” Holt recalled decades later as he prepared to retire. “But I knew very definitely what I did not want in the way of educational methods. I had suffered under the lecture-and-recitation system too long for too many years not to know how seriously [such a system] may handicap any real flowering of a student’s mind; how eagerness may be replaced by indifference and finally boredom.”

Holt’s solution was the so-called “conference plan,” which replaced lectures with discussions and one-on-one interactions between professors and students. He also insisted that the college limit enrollment and recruit professors who were first and foremost skilled teachers — “golden personalities,” he called them.

In 1931, Holt organized a high-profile colloquium on liberal-arts education led by renowned educational philosopher John Dewey. Ultimately, the conferees validated what Holt had called “a common-sense approach to higher education,” and endorsed key aspects of the conference plan and other reforms — including the elimination of grades and the reduction of specific course requirements.

Holt also started the Animated Magazine, which each winter brought celebrities and prominent personalities to campus for a day of public presentations. Rollins, it seems, was constantly getting national attention for one initiative or another, thanks to the president’s background as a journalist and a promoter of causes.

In addition, Holt presented a plethora of honorary degrees to attract luminaries to campus and keep the college in the news. Most of the recipients did, in fact, warrant the recognition.

“Hamilton, if you’re about to tell me that the Roosevelts have accepted an invitation to come here, and that you want to have the convocation in the chapel, don’t forget I gave that chapel to the college not with any strings attached. It’s for you to use as you see fit. So, if that’s the purpose of all this, you’re wasting your time. I just have one request. Don’t ask me to be in town when those people are here, because I will not be here when they’re in town.”

—Frances Bangs Knowles, on word that President Franklin D. Roosevelt would visit Rollins

In 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt arrived to receive an LHD (an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters) in ceremonies at Knowles Memorial Chapel. (Eleanor Roosevelt received the Algernon Sydney Sullivan medallion, prompting her husband to remark that it was the first time he had seen his “better half” in a cap and gown.)

Many conservative Winter Parkers despised FDR, but most — in that simpler time — respected the office of the presidency and held their tongues. John “Jack” Rich, in his 2005 oral history interview with Wenxian Zhang, head of the college’s archives and special collections, recalled the reaction of Rollins chapel benefactor Frances Knowles Warren to the Roosevelts’ visit:

“The residents of Winter Park were very conservative, dyed-in-the-wool Republicans … who hated the name Roosevelt. So when [Holt] finally worked out the date for the Roosevelts to come… [he] thought it would be a polite gesture to let Mrs. Warren know. … She said, ‘Hamilton, if you’re about to tell me that the Roosevelts have accepted an invitation to come here, and that you want to have the convocation in the chapel, don’t forget I gave that chapel to the college not with any strings attached. It’s for you to use as you see fit. So, if that’s the purpose of all this, you’re wasting your time.’ And she said, ‘I just have one request. Don’t ask me to be in town when those people are here, because I will not be here when they’re in town.’”

“[Holt’s] old friends were not at all surprised when he substituted new ideas in education for old practices,” said Roosevelt. “These changes at Rollins are bearing fruit. They are being watched by educators and laymen. The fact that in some respects they break away from the old academic moorings should not startle us.”

Added Roosevelt: “In education, as in politics and economics and social relationships, we hold fast to the old ideals and only change our method of approach to the attainment of the ideals. Stagnation follows standing still. Continued growth is the only evidence of life.”

But one thing never changed, and that was Holt’s passion for world government. For a time, his crusading was subsumed by his duties as a college president. But as his early educational innovations became established, he increasingly returned to what he considered to be his most important life’s work — and used the college as a sort of bully pulpit.

A world again spiraling out of control may have prompted Holt to renew his activism. He supported the allied effort in World War II and, when the war ended in 1945 after atomic blasts devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he traveled to San Francisco as an independent observer when a charter was adopted establishing the United Nations.

He deemed the resulting organization only a marginal improvement over the soon-to-be defunct League of Nations, which had limped along without the United States and had notably failed to prevent yet another world war as its members dropped out (or were expelled, as was the case with Russia) and became combatants.

With the advent of nuclear weapons, Holt believed, it was more important than ever that a world government — not any independent nation — should control such awesome destructive power.

The United Nations, he said, must be “transformed from a league of sovereign states into a government deriving its specific powers from the peoples of the world.” Realizing that this was unlikely, Holt insisted that someday — perhaps not in his lifetime — nations would join “in one universal brotherhood, in which cooperation shall succeed competition, faith shall supplant fear and law shall expel war.”

In February 1946, Holt had an opportunity to personally deliver what he called “an open sermon” to President Harry S. Truman, who was in the midst of a whirlwind trip to Central Florida and stopped by the college to receive an honorary degree of his own. The steely Missourian’s Founders’ Week appearance came at a time of increased tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies. That struggle for global dominance, destined to span decades, would soon become known as the Cold War.

“We are working for peace,” vowed Truman, who likely anticipated — and just as likely did not wish to hear — an admonition from Holt. “We want peace. We pray for peace all the time in the world. And to attain that peace we must all learn how to live together peaceably and to do to our neighbors as we would have our neighbors do to us. Then we will have a happy world. And that is what we all want.”

Holt, in turn, repeated much of his now-familiar world government stump speech and argued that Truman’s military buildup was as likely to cause conflict as to preserve peace.

“The fact is there is no such thing as absolute preparedness,” he said. “That is why the generals and admirals are never satisfied.” Yes, Holt acknowledged, the Soviet Union almost certainly intended to “extend her political ideologies to the outside world and thus eventually abolish capitalism, if not democracy.”

But the answer, he continued, was not “feverishly to arm ourselves against an impending World War III.” Truman should instead call for the United Nations to revise its charter and reconstitute itself as a “world government with direct power to tax, conscript and otherwise make and enforce laws.”

Holt claimed that he did not know what the domestic political ramifications of such a stance would be for Truman. He insisted, however, that in the grand scheme of things it hardly mattered.

“If you are reelected you will have four more years to carry out your great design,” Holt said. “If, however, you are defeated, you will still have the acclaim of millions of mankind as well as the personal satisfaction of having done more than any living man to put this great ideal into the minds and hearts of your fellow men.”

How would a world government deal with a recalcitrant Soviet Union? “We might have to set [it] up without Russia and her satellites,” Holt conceded. “But sooner or later, all the outside nations will come in.”

Although he tempered his remarks during convocation, he had previously opined that any nation — most notably Russia — that rejected United Nations control over atomic energy “should be wiped off the face of the earth with atomic bombs.”

“If you are reelected you will have four more years to carry out your great design. If, however, you are defeated, you will still have the acclaim of millions of mankind as well as the personal satisfaction of having done more than any living man to put this great ideal into the minds and hearts of your fellow men.”

—Hamilton Holt in an “open lecture” to President Harry S. Truman about stopping the arms race

Truman, of course, never went so far as to endorse world government. But at the 1948 dedication of a war memorial monument in Nebraska — and speaking specifically of arbitration — he sounded very much like Holt when he said that international disputes between nations should be solved in the same way as disputes between states within nations:

“When Kansas and Colorado fall out over the waters in the Arkansas River, they don’t go to war over it; they go to the Supreme Court of the United States, and the matter is settled in a just and honorable way. There is not a difficulty in the whole world that cannot be settled in exactly the same way in a world court.”

Holt’s stance, though, went far beyond an obvious nod to the value of arbitration over armed conflict. Philosophically, he was closer to Klaatu, the intergalactic emissary, but without a shimmering spacesuit and a robot companion. He wanted nothing less than an end to war — even if it meant obliterating warmongers.

World Government on Campus

In March 1946, almost immediately following Truman’s on-campus appearance, Holt convened the Rollins College Conference on World Government, inviting 40 like-minded luminaries — 25 of whom traveled to Winter Park. Among them were representatives from academia, industry, politics and the clergy.

After several days of discussion, the group, chaired by historian Carl Van Doren, adopted an “Appeal to the Peoples of the World.” The three-page document, which mirrored Holt’s convocation speech, called for creation of a world government “to which shall be delegated the powers necessary to maintain the general peace of the world based on law and justice.”

Conferees agreed that the United Nations, toothless in its present form, at least provided a ready framework — much as the League of Nations had more than 25 years before — and could be reconstituted as a legislative body that would regulate the use of atomic energy, impose civil and criminal sanctions against violators of international law and, if necessary, launch military action against malefactors.

Although practical detail, as usual, was missing, the document was signed by 80 prominent individuals. Theoretical physicist Albert Einstein, whose warning to FDR about Germany’s atomic research had spurred the Manhattan Project, was among the absentee signatories.

Others who were not in attendance but who signed the document included Justice William O. Douglas of the U.S. Supreme Court; Florida U.S. Senator Claude Pepper, who later served in the U.S. House of Representatives; and California U.S. Representative H. Jerry Voorhis, who is remembered for losing his seat to a Red-baiting novice named Richard M. Nixon.

Holt’s son, George, who had graduated from Rollins and was now its director of admissions, chaired the conference. Also in attendance was Edwin S. Slosson, Holt’s colleague from The Independent who had written Great American Universities, and Ray Stannard Baker, a muckraking journalist whose eight-volume Woodrow Wilson: Life and Letters (1927–1939), won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography in 1940.

Holt, rather hyperbolically, declared the committee’s proposal to be “the soundest, most advanced and most statesmanlike yet issued to the world by men of high distinction and responsibility.”

He also announced that the college would launch an Institute for World Government led by 25-year-old Rudolph von Abele, an assistant professor of English who had been active in the world peace movement during graduate school at Columbia University.

When von Abele did not return to the college in 1947, the fledgling operation, the purpose of which was to promote internationalist ideals, was placed under the supervision of professor of mathematics George Sauté, who would later direct the college’s reconstituted adult education program.

Holt headed the executive committee, which also included E.T. Brown, college treasurer; Edwin L. Clarke, professor of sociology; Royal W. France, professor of economics; Nathan C. Starr, professor of English; and Mary Upthegrove, a student active on the Inter-Racial Committee and the Pan-American League.

The executive council included students Weston Emery, Eleanor Holdt, Marcia Huntoon, Tony Ransdell and Phyllis Starobin. Wendell C. Stone, the college’s dean; Horace A. Tollefson, the college’s librarian; and Alex Waite, professor of psychology, also served.

No longer solely a personal crusade, Holt had aligned the college with a cause that was surely going to cause controversy in the community as well as among donors and trustees.

In October 1947, Holt sent Sauté to the Convention of the United World Federalists in St. Louis, where more than 300 earnest activists representing 37 state chapters gathered to chart a course forward.

The movement was, in fact, enjoying a brief resurgence in the years between the end of World War II and the start of the Korean War. Gallup Polls in 1946, 1947 and 1948 asked: “Do you think the U.N. should be strengthened to make it a world government with the power to control the armed forces of all nations, including the United States?”

In each of those three years, around 55 percent said yes. The number began dropping in 1949 and bottomed out at 40 percent in the mid-1950s. After two world wars in little more than 20 years, it appears that many in the mid-1940s were at least willing to listen.

Several months prior to the St. Louis gathering, world government advocates from 51 countries had gathered in Montreux, Switzerland, for the grandly named Conference of the World Movement for World Federal Government.

The resulting Montreux Declaration stated that “the United Nations is powerless, as at present constituted, to stop the drift of war” and opined that only the establishment of world government “can ensure the survival of man.”

Following this conclave, five smaller world government organizations — representatives of which had attended the meeting in St. Louis — merged to form the United World Federalists, which was based in Asheville, North Carolina.

Although there were internal disagreements, ultimately the attendees agreed that world government should be brought about through changes to the United Nations charter. As reconstituted, the organization would take ownership of nuclear technology and prohibit any nation from possessing arms deemed to be beyond the level required for internal policing.

There would be no wiggle-room or opt-out clauses. National governments would agree “to the transfer to the world federal government of such legislative, executive and judicial powers as relate to the world affairs.” Miscreants would answer to “a supranational armed force capable of guaranteeing the security of the world federal government and of its member states.”

Sauté, who had been hired by Holt in 1943 and shared his internationalist fervor, was energized by the trip. “This crusade is not one to join, talk about, go home and forget,” he reported to Holt upon his return. “It is a crusade that will continue until a rule of law is established for the settlement of international disputes; then and only then can we enjoy lasting peace.”

Clearly Sauté was preaching to the choir with Holt, who was nonetheless pleased to have found a faculty surrogate with whom to share the burden of advocacy.

In January 1948, the Rollins Institute for World Government hosted a meeting of the Florida UWF branch, which included delegations from chapters in Kissimmee, Lakeland, Orlando, Tampa and Winter Park. Sauté was elected state chairman, and it was agreed that Rollins would become state headquarters.

When the meeting concluded, an editorial in The Sandspur by Samuel R. Levering, a Quaker pacifist from Virginia who was among the founders of UWF, lauded Holt’s vision and listed prominent public supporters of world government, including activists, academicians, several industrialists and two U.S. Supreme Court Justices.

The world government movement was neither communist or socialist, Levering wrote, and its lofty goals were “much more practical than the alternative — continuing the arms race with destructive war almost certain.”

But what about Russia? Would it participate in such an organization? Levering had an answer:

“If Russia refuses, the rest of the world should go ahead anyway, leaving the way open for Russia to come in later. Should Russia stay outside, the rest of the world, united, would be stronger than at present, since Russia, isolated and in a worse moral position, would be less likely to attack.”

In any case, Levering concluded, time was of the essence “if our civilization is to survive … and World War III is to be prevented.”

Sauté, who possessed the physical endurance that Holt, now past 70, found more difficult to muster, began lining up speaking engagements. Although he was not an orator of Holt’s caliber, Sauté addressed virtually every civic group in Central Florida and many around the state.

One headline announcing a Sauté presentation most accurately described his ambitious objective: “Sauté Charts Course Needed to Save World.”

In addition, Sauté became a prolific writer of letters to the editor, and while his missives lacked Holt’s literary flair, they were effective in their forthright fashion.

“Some people say we cannot hope to have a world government until nations understand each other better and are willing to cooperate,” he penned in a 1948 edition of the Winter Park Herald. “They add that you should have peace at home, in your community and in your country before you talk about world peace.”

The column continued: “Why do some think that the protection of law is all right up to the level of nations but shrink from the idea of extending it to the international level? There is nothing whatsoever that we are advocating … that denies the necessity of our country’s keeping a strong military until world government is established. Our strong contention is that we will not prevent war by preparing for it and doing nothing else.”

Sauté even launched a weekly radio program, World Government and You, on Orlando station WORZ-AM, and was interviewed over Voice of America radio speaking entirely in French (having been raised in Belgium, he was fluent in the language).

Yet Sauté seemed an unlikely crusader, according to a profile in a local weekly, The Corner Cupboard: “A man with an enviable philosophy of life is George Sauté. He lives life as it comes, day by day, with a deep conviction in the power of prayer to set things right. In his own affairs, Prof. Sauté takes a middle-of-the-road position. He is not one to have more courage than wisdom. Rather, his is a moral courage that has the patience and the self-control to await the outcome of events.”

Holt, in the meantime, could not afford to wait for anything. He wore himself out chasing money; in May 1947, following the groundbreaking for Orlando Hall, he was hospitalized following an emergency appendectomy and spent much of the summer recovering at his home in Woodstock.

“I see a bend in the river and try to tell myself that if I reach the turn, the water will be calm. But I know that is not so. When a problem is solved, there are others to take its place.”

—Hamilton Holt on his lifelong peace activism

“No one will ever know how hard [Holt] and his assistants worked during the late stages of the drive,” reported the Rollins Alumni Record. “This tremendous effort drained his physical strength and undoubtedly contributed to his illness.”

The story continued: “[Holt] personally wrote hundreds of letters, sent innumerable telegrams and made countless long-distance telephone calls in his appeal for funds. [He] felt there was nothing else to do but put his whole strength into the undertaking or he would probably not reach his goal — and he says that he would do it again.”

The twin responsibilities of keeping the college solvent and saving the planet weighed on Holt’s health and surely on his psyche. “During a crisis I feel like a man battling a current,” he reflected in 1949, as he prepared to retire.

“I see a bend in the river and try to tell myself that if I reach the turn, the water will be calm. But I know that is not so. When a problem is solved, there are others to take its place.”

Holt’s health had been in precipitous decline since his leg had been amputated due to diabetes. A seeker of peace, he finally found it on April 26, 1951, when he died of a heart attack at his home in Woodstock.

The Last Crusader

The beloved “Prexy,” as Holt was known, was replaced by Paul A. Wagner, a brilliant but arrogant 32-year-old wunderkind who, among other affronts, fired one-third of the college’s teaching staff, many of whom had earned tenure. It was a budgetary matter, he said.

Sauté’s job was among those on the chopping block. But, following an imbroglio that dragged on for nearly two years, Wagner was fired and, after much drama, evicted from the campus. Holt protégé Hugh F. McKean, a professor of art, was named president in 1951 and promptly rehired the dismissed faculty.

But the Institute for World Government was eliminated, ostensibly because there were no funds available. More likely, the institute was a casualty of Cold War wariness.

With McCarthyism and the Red Scare running rampant, internationalists often found their names on lists of communists and other fellow travelers. In any case, the college was in no position to agitate anyone.

“When I first started lecturing on the United Nations, atomic energy and international control of armaments for peace, it was popular,” said Sauté in a 1969 oral history interview. “And then suddenly it got very unpopular. I would be lecturing or debating, and someone would say, ‘You’re from Belgium, aren’t you? Well, then you’re not an American.’”

Further, although McKean was an admirer of Holt, he was no crusader, and did not share his mentor’s political fervor. He had a college to save, after which, it was then assumed, he would return to teaching, curating and painting.

Instead, he would serve as president for 18 years, retiring in 1969 and founding the Morse Museum of American Art with his wife, Jeannette. McKean died in 1995 at age 86.

Sauté went on to direct Courses for the Community, a modest adult education program that eventually evolved into the Hamilton Holt School. However, the quality of the program never met McKean’s amorphous standards, and Sauté was frequently the recipient of terse memos from his boss threatening to shutter adult education altogether unless improvements were made.

Perhaps that is the primary reason that on McKean’s way out, he made certain that the mild-mannered mathematician, who had reached the college’s mandatory retirement age of 65, would also be put out to pasture.

After 26 years, Sauté was not reappointed — over his vigorous protest — and died in 1986 at age 83.

World federalism has not gone away. Today, the World Federalist Movement-Institute for Global Policy, based in The Hague, Netherlands, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization “committed to the realization of global peace and justice through the development of democratic institutions and the application of international law.”

While Holt’s world government crusade may have been hopeless from the outset and especially off-putting to conservative Winter Parkers, no one doubted his deep-seated desire to render war obsolete.

Two world wars occurred in Holt’s lifetime, and the human toll of war impacted him deeply. Little wonder that he undertook the Sisyphean task of trying to change what was likely not changeable.

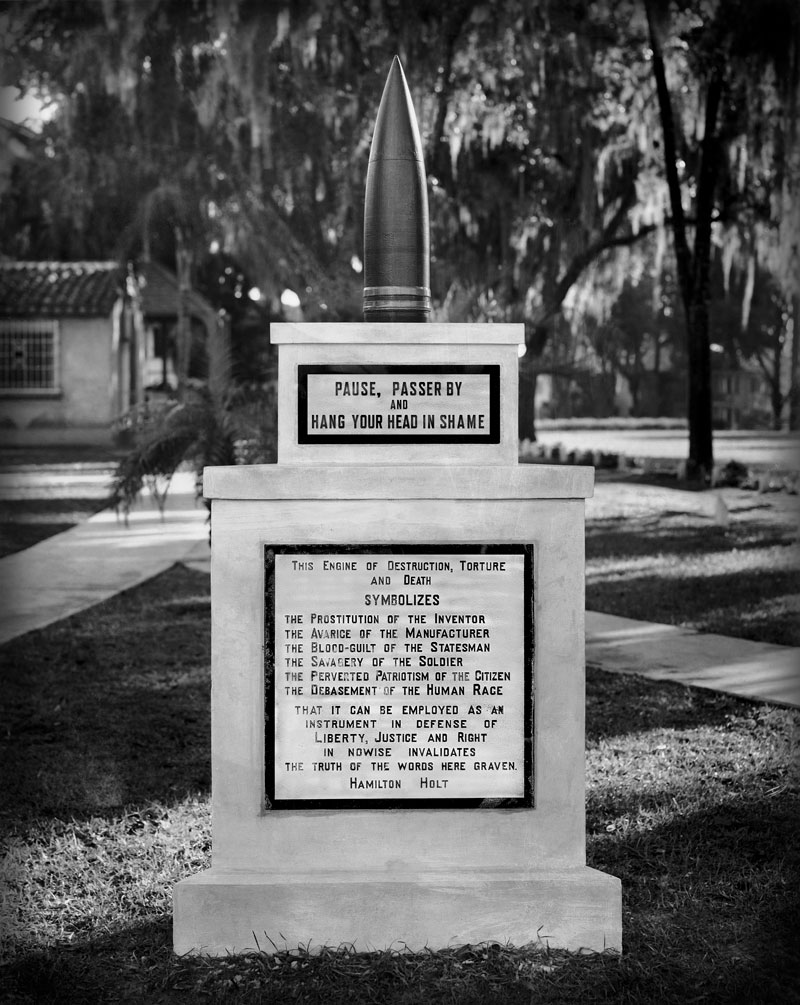

Holt’s outrage over war in general would be exemplified in mortar and steel on the Rollins campus in 1938, when his Peace Monument was unveiled in front of Lyman Hall. Dedicated on Armistice Day, the monument was emblazoned with a powerful message:

“Pause, passerby, and hang your head in shame” was written beneath a World War I-era German mortar shell presented to Holt by his friend Poultney Bigelow, co-owner of the New York Evening Post. Affixed to the monument’s base was a plaque with text written by Holt that read:

“This engine of destruction, torture and death symbolizes the prostitution of the inventor, the avarice of the manufacturer, the blood-guilt of the statesman, the savagery of the soldier, the perverted patriotism of the citizen, the debasement of the human race; that it can be employed as an instrument in defense of liberty, justice and right in nowise invalidates the truth of the words here graven.”

In August 1943, the Peace Monument was destroyed in an act of vandalism.