Exclusive Book Excerpt

Editor’s Note: The following is a revised and condensed version of a chapter from a 2019 book entitled Rollins After Dark: The Hamilton Holt School’s Nontraditional Journeys. This chapter focuses on the children’s programs that were launched by President Hugh F. McKean as a community outreach effort in the aftermath of Paul A. Wagner’s brief but tumultuous presidency, which left faculty and students stunned and the community deeply divided. The programs, eventually assembled under the umbrella of the Rollins College School of Creative Arts, were introduced concurrently with adult education efforts that eventually evolved into today’s Hamilton Holt School.

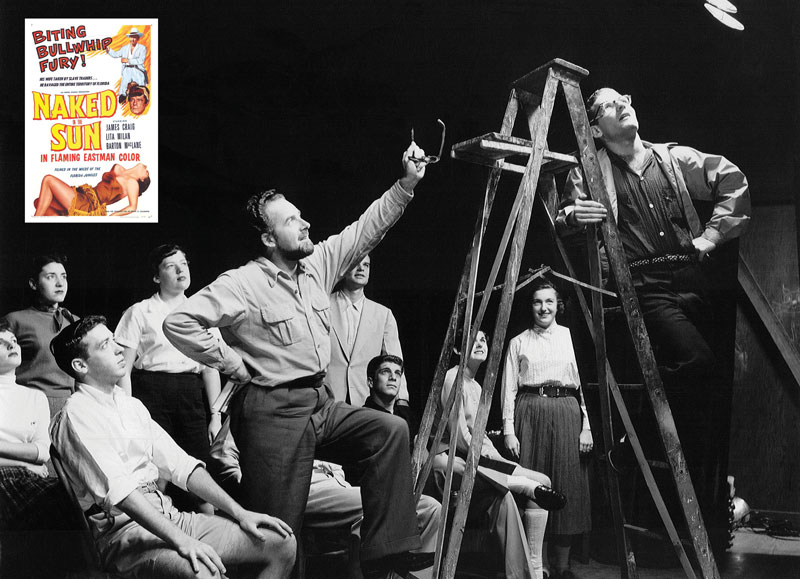

Photo Restoration and Colorization by Will Setzer at Circle 7 Studio

Anarchy on Ollie Avenue? An overstatement, perhaps, but it can certainly be said that Community Courses for Young People — launched at Rollins College in 1951 by new President Hugh F. McKean — brought children to the campus in droves: singing children, dancing children, painting children, acting children, swimming children, weaving children and musical-instrument-playing children.

Community Courses for Young People was initially directed by George Sauté, a professor of mathematics whom McKean had tapped to strengthen ties between the college and the community by offering educational and recreational programs for local residents.

The impetus for doing so was likely fallout from the divisive debacle of Paul A. Wagner’s brief presidency, which roiled the campus and divided the community. (See “A Master Class in Chaos” in the Fall 2020 issue of Winter Park Magazine.)

Thousands of present-day baby boomers fondly recall attending after-school classes, which were sometimes taught by highly credentialed day school faculty, or the program’s popular Summer Day Camp, which began in 1967 and ran through the summer of 2015.

Community Courses for Young People — an ancillary program to Courses for the Community, which would decades later evolve into today’s Hamilton Holt School — offered after-school piano lessons as well as rhythmics (dance), choral singing, junior theater, and arts and crafts. Headquarters was a barracks-like studio on Ollie Avenue, behind the infirmary near Dinky Dock. (Today the parcel is home to the college’s massive parking garage.)

Lessons in other musical instruments were added, along with instruction in swimming and canoeing. By the late 1950s, each eight-week quarter attracted more than 500 youngsters from pre-school to high school.

ROAR OF THE GREASEPAINT

From 1953 to 1958, students from the young peoples’ program commandeered the 400-seat Annie Russell Theatre for The Spring Thing, a collection of short plays, some of them original, as well as scripted and improvised skits.

During the show’s run, art students created works to be displayed in the lobby, while crafts students helped to create sets, props and costumes. Music students provided accompaniment, and beaming parents packed the venue for performances.

British-born actor Peter Dearing, director of the college’s Department of Theater Arts and an instructor for the young peoples’ program, offered his energetic charges numerous opportunities to perform with the Rollins Players onstage at “the Annie.”

A former professor at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts in London, Dearing began his career as a curly-haired child actor in films before touring the U.S. and Europe with the Ben Greet Players, a stock company that specialized in open-air Shakespeare productions.

Ben Greet was the stage name for Sir Philip Barling Greet, who may have inspired Dearing’s interest in children’s theater. When Greet managed London’s Old Vic theater from 1914 to 1918, he persuaded the U.K. Department of Education to sponsor school visits to the historic 1,000-seat venue.

Over the course of four years, Greet presented Shakespeare plays to more than 20,000 elementary school students. Dearing joined the Ben Greet Players at age 14 and remained until Greet’s death nine years later. He clearly understood how to relate to children with a theatrical bent.

In 1955, Dearing cast 9-year-old Annette Moore and 12-year-old Danny Carr in an Annie Russell Theatre production of Mrs. McThing, a fantasy about children and witches written by Mary Chase of Harvey fame. Although a critic from The Sandspur savaged the play, opining that “the progression of innumerable ideas is exceedingly awkward,” he managed to coherently praise young Annette for “stealing the show” with her poise and stage presence.

Also appearing in Mrs. McThing was Rollins drama student Ann Derflinger, who would become a legendary drama teacher at Winter Park High School. The auditorium at the school is named for Derflinger, who died of cancer in 1983. She often cited Dearing as a major influence on her decision to teach. Derflinger, in turn, inspired actors such as Tom Nowicki (The Blind Side) and Amanda Bearse (Married With Children), both of whom were her students.

Dearing later drafted talented young peoples’ program participants for campus productions of The Crucible and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. And in 1957, when he directed Maxwell Anderson’s The Bad Seed for the Orlando Players, a community theater production, Dearing plucked a junior-high schooler for a plumb role.

Precocious Anne Hathaway, 11, chewed up the scenery as pigtailed psychopath Rhoda Penmark in a performance the Orlando Sentinel described as “brilliant … [Anne] was able to project a chilling ruthlessness, which told her audience that under the smile a twisted brain was plotting murder.”

Also that year, Dearing notched his only U.S. film credit, a small role in Naked in the Sun, a low-budget effort about the Seminole Indian warrior Osceola. Although ostensibly set in the Everglades, Naked in the Sun was shot primarily (and appropriately) in Osceola County. Despite lurid posters and “flaming Eastman color,” the film descended into obscurity following its grand premier at Orlando’s Beacham Theater.

Dearing left Rollins shortly thereafter to become artistic director at the Grand Theatre in London, Ontario, where he gained a reputation for staging lavish musicals such as The Boy Friend, Oliver, West Side Story and My Fair Lady. He died in 1971 at age 58, and memorial services were held at the venue’s main auditorium.

TICKLING THE IVORIES

Marion Marwick, a pianist who had tickled the ivories with the Toronto Symphony and the Orlando Symphony Orchestra, enjoyed playing jazz — and was good at it. She also enjoyed teaching others to play the piano, and was among several adjunct instructors in 1957, when Community Courses for Young People was inexplicably renamed Community Courses for Children.

She later became director of the program’s music division and, still reporting to Sauté, was named director of all activities under the auspices of the newly formed Rollins College School of Creative Arts. The school subsumed the children’s program — including the Summer Day Camp — following a reorganization in 1962.

Under the energetic Marwick, a graduate of the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, piano instruction dominated after-school offerings. By Marwick’s account, she taught more than 1,000 people of all ages to play during her career.

“Everyone who took piano lessons from my mother loved her,” recalls Robert Marwick, her son. “She was dedicated. She built that program into a major force in the community and something that meant a lot in the lives of young people.”

Indeed, a social media post from Robert Marwick seeking memories of his mother drew dozens of nostalgic responses recounting how Mrs. Marwick had made a difference — as good piano teachers often do — by becoming a friend and confidant.

Marwick’s jaw-dropping student count, however, was possible because in addition to individual instruction she was an exponent of the Pace Method — created by pianist and educator Robert Pace — which advocated teaching piano in large groups. The School of Creative Arts was one of the first in the U.S. to adopt the method.

Pace, director of the piano department at Teachers College, Columbia University (from which he had earned a doctorate) and director of the National Piano Foundation, consulted with Marwick and visited Winter Park each year to check the program’s progress.

Visitors to the School of Creative Arts when it moved to R.D. Keene Hall in 1974 (location of the college’s Virginia S. and W. W. Nelson Department of Music) remember the second floor as containing dozens of pianos of every sort, many side by side, and youngsters playing them while wearing headphones.

By the mid-1960s, the burgeoning school offered nearly 30 courses per term and attracted some 1,200 students who could choose from sessions in piano, voice, brass and woodwinds, violin and viola, and guitar and banjo. There was also instruction in painting and sculpture, ceramics and weaving and, somewhat incongruously, conversational Spanish and French.

An annual Rollins Piano Festival of the School of Creative Arts was launched and drew music students and educators from around the U.S. Pace, among others, attended as an adjudicator for student competitions. Marwick, who left Rollins in 1970 to begin a private piano instruction school called Creative Keyboards, died in 2005 at age 81.

PHONSIE’S LASTING LEGACY

Most classes in Community Courses for Young People — and later the School of Creative Arts — were taught by adjunct faculty, often teachers from Orange County Public Schools. One prominent college music professor, however, found a mission through the program and in so doing created a lasting but underappreciated legacy by establishing the Florida Symphony Youth Symphony.

Violinist Alphonse “Phonsie” Carlo, during an interview for a job at the college’s music department — then known as the Rollins College Conservatory of Music — was asked by Rollins President Hamilton Holt, who had sung first tenor in the Yale Glee Club, if he could play an Irish folk song, “Londonderry Air.”

The tune, which originated in County Londonderry in Ireland, is used as the victory anthem of Northern Ireland at the Commonwealth Games, an international multisport competition. But anyone who has ever heard the popular ballad “Danny Boy” will recognize “Londonderry Air,” from which the melody is appropriated.

Carlo, who studied violin at Yale University and the Julliard School of Music, deftly fulfilled Holt’s request, accompanied by the president on an old stand-up piano stationed in his office. A delighted Holt offered Carlo a job as an assistant professor of music in 1943.

In 1953, Carlo was recruited to teach violin through Community Courses for Young People. By all accounts a kind and patient man who enjoyed instructing students of all ages, Carlo agreed and offered after-school lessons, as did his accomplished wife, Katherine, a concert pianist with whom he frequently performed.

Shortly thereafter, Carlo persuaded the Orange County School Board and the Florida Symphony Orchestra — for which he had become concert master — that a youth orchestra would benefit everyone involved.

Through such a program, schools could offer orchestral training without the expense of starting orchestral programs. And the symphony could develop players-in-waiting while expanding its base of support through the proud parents of school-age musicians.

Announcements were made and an article was published in the Orlando Sentinel. On the first Saturday in November 1953, more than 100 students from middle school through high school, their instruments in tow, assembled at Howard Junior High School.

On subsequent Saturdays, there were free classes for beginning and intermediate players followed by a rehearsal for students who were sufficiently advanced to become the first members of the Florida Symphony Youth Orchestra. Assisting the busy Carlo, who also played in a baroque ensemble, were several other symphony players and public-school music teachers.

Glenridge Junior High School was the first local public school to form an orchestra, in 1957. (Winter Park High School did not have an orchestra until 1962.) Forming a competent, much less a good, youth orchestra was no small feat in 1953, when the music programs in most public schools were centered upon brass-heavy marching bands.

Still, Carlo had a gift for recognizing and cultivating young talent. In 1954, the 30-member youth orchestra — perhaps seeded with some more experienced collegiate ringers — played alongside the professionals at the Florida Symphony Orchestra’s annual Spring Pops Concert at Orlando Municipal Auditorium (now the Bob Carr Theater).

“I’ve never seen a group of students with more self-discipline and more earnestness in their work,” said Edward Preodor, head of the violin department at the University of Florida in an interview with the Orlando Sentinel.

Continued Preodor: “Students who will give up their Saturday mornings to study are the best type of students. But more important still is the leadership of your conductor, Alphonse Carlo. He is obviously a leading musician who understands young people and who loves to work with them.” The fledgling youth orchestra also performed solo concerts, including at least two that were televised locally.

Carlo stepped down as conductor in 1960, but remained a steady and supportive presence. The college covered some operating expenses and was listed for several years in the 1970s as the youth orchestra’s sponsoring organization — although the nature of the partnership appears to have been informal.

The Florida Symphony Orchestra’s Women’s Committee, meanwhile, provided scholarships for young players to study with Carlo and others at the School of Creative Arts. The youth orchestra, despite its popularity, received scant attention from the professional orchestra’s management team until 1978, when it was granted “full arm” status.

Ironically, the junior partner emerged unscathed even after the senior partner collapsed under financial pressure in 1993.

“Because we remained attached at the hip for so long, our historical narrative has been told from the Florida Symphony Orchestra’s perspective,” says Don Lake, president of the youth orchestra’s board of directors. “But Rollins College, through its former School of Creative Arts, was a profound co-sponsor and financial supporter. Our organization would not even exist without the help the college gave us.”

Today, Phonsie’s pet project is a thriving 501(c)(3) organization with three full orchestras, a string training orchestra, a chamber music ensemble and a 24-piece jazz orchestra. While Rollins is rarely given credit, the Florida Symphony Youth Orchestra can trace its beginnings to Community Courses for Young People and the School of Creative Arts.

The legacy of the Carloses continues in other ways. The Alphonse and Katherine Carlo Music Scholarship, which was established in 1993 thanks to a gift from the Alphonse Carlo Trust, provides scholarships for students to study piano or stringed instruments. There is also a Carlo Room in the R.D. Keene Music Building. Katherine Carlo died in 1990; her husband died in 1992.

A LONG GOODBYE

Whatever happened to the Rollins children’s programs and the School of Creative Arts? It is indeed a long and convoluted story. But essentially McKean — who started the program — lost interest in it as his determination to establish a full-fledged, degree-granting adult education program grew.

In 1960, McKean announced formation of the Institute for General Studies, which encompassed three divisions: Courses for the Community, which included the School of Creative Arts; the Graduate Programs, which offered an MBA as well as advanced degrees in physics and teaching; and the School of General Studies, which would for the first time in the college’s history offer an undergraduate degree — a Bachelor’s Degree in General Studies — to adult learners.

Although the institute had no dean, Sauté directed Courses for the Community and the School of General Studies. The Rollins Alumni Record described the programs as “much more than a fine community gesture” and lauded Sauté as “not interested in press clippings and service awards; he is interested in education.”

His boss, however, had no qualms about generating press clippings. The following year, McKean attempted to launch a so-called Rollins College Space Institute, which he envisioned would become the crown jewel of the School of General Studies.

Despite much hoopla — and lavish media coverage — the liftoff fizzled and the project was never mentioned again in print after 1963. However, the mercurial president continued to be intrigued with new ideas for expanded offerings — none of them involving children’s programs.

When McKean did take note of the School of Creative Arts, he seemed annoyed — perhaps embarrassed — by its presence. Several times, in fact, he threatened to shutter the program over administrative snafus.

“I have appointed no one to teach in the [School of Creative Arts] for this fall term,” McKean wrote in a 1962 memorandum to Marwick. “If anyone is actually teaching, by this memorandum I will direct the treasurer to discontinue their salaries. No department of this college can or should make laws for itself. Unless the [School of Creative Arts] can conform to the principles and practices of the college, I will recommend to the trustees that it either be discontinued or reorganized.”

While McKean was justified in insisting that Marwick follow established protocols, such as securing proper approvals for instructor appointments, his tone seemed unduly harsh. The school was, after all, a nonacademic, noncredit program that primarily taught arts, crafts and music to children.

It is also not quite clear why McKean did not first take the matter up with Sauté, who was nominally Marwick’s supervisor. But Sauté, too, at times incurred the patrician president’s icy ire. In a 1963 memo, McKean expressed concern to Sauté about the caliber of the adjunct faculty in the institute’s degree-granting program.

“No one who would not qualify as a member of the College of Liberal Arts is to teach in the Institute for General Studies,” McKean wrote. “Unless it is possible for us to maintain identical standards in the institute and the liberal arts college, I will recommend that the trustees discontinue the institute at the end of the year.”

Frustrated by what he felt were mediocre programs but unwilling to invest in their improvement, McKean was surely elated in 1964, when the college received a $1 million gift from financier Roy E. Crummer. Now here was something McKean could be proud of — a prestigious, well-funded graduate school that didn’t draw comparisons to a kindergarten, a country club or a community college (then called junior colleges).

The funds were used to build and endow the Roy E. Crummer School of Finance and Business Administration (now the Roy E. Crummer Graduate School of Business), which originally offered both MBA and Master of Commercial Science degrees.

Said McKean: “[The Crummer School] will help to strengthen the human element in business. It will strive to make men of its students, not machines. The business world needs leaders prepared to think responsibly, not rely on pushing buttons and pulling levers.”

With the MBA program now having its own dean, McKean dropped the Institute for General Studies and formed the Central Florida School for Continuing Studies, which had responsibility only for Courses for the Community, the School of Creative Arts and a branch campus at Patrick Air Force Base in Brevard County. Sauté was retained as the school’s director.

Still, McKean never embraced the School of Creative Arts, nor the multi-named, all-purpose adult education program under which the children’s activities operated. Perhaps he had come to believe that they were detrimental to the college’s vision of itself as a serious academic institution.

Yes, he had allowed both programs to continue — but he complained about them constantly and never articulated a path forward that would gain his favor. The fence-mending outreach initiatives that had seemed so important a decade earlier now seemed to have become annoyances, especially as the Wagner debacle faded into memory.

As McKean approached retirement age, he continued to put forth big ideas. In 1967, he made headlines with a proposal to create a national university through which a student of any age and in any location could earn a low-cost bachelor’s degree through courses on television and radio, videotape recordings and correspondence instruction without setting foot on a physical college campus.

“We cannot send everyone to college,” he said. “But we can send college to everyone.” The idea presaged later notions of virtual universities and the “colleges without walls” concept.

McKean, who had become an iconic figure in the region through his high-profile presidency, announced that he would retire and assume the newly created role of chancellor by the beginning of the school year in September 1969.

“I’m just an old art teacher,” he would later tell the Orlando Sentinel. And perhaps he would have preferred just to paint, ensconced in his Park Avenue “scriptorium” (an apartment studio above the Winter Park Land Company) turning out haunting, impressionistic images dominated by blues, greens and blacks — some containing the sort of supernatural elements, such as ghosts and angels, often found in folk art.

McKean, however, would not be the only departure from Rollins in 1969. In February of that year, Dean of the College Donald W. Hill sent a brief memo to the president: “Mr. Sauté, age 65, may be retired, if desired.”

Obviously, McKean desired precisely that. In March, he notified Sauté by letter that it was his “unpleasant assignment … to tell you that the board of trustees have agreed, in view of the fact that you are 65 years of age, not to reappoint you to the position of director of the Central Florida School for Continuing Studies (previously known as the School of General Studies.)”

Sauté was thanked for his years of service and offered an opportunity to teach — likely at an adjunct’s stipend — if he wished. The mathematician, however, resisted. He was healthy and, in his estimation, had done a good job given the limited resources at his disposal.

True, enrollment in his program had dropped from a peak of 1,155 in 1966 to 828 in 1969, but Sauté had planned to introduce new courses for law enforcement officers as well as programs for public servants in recreation, finance and fire safety.

Further, the School of Creative Arts, which Sauté allowed Marwick to run as she saw fit, had launched a successful Summer Day Camp two years prior — more than 1,000 youngsters attended its programs — and it had continued to foster goodwill in the community.

But McKean would not back down — he had, in fact, already extended an offer to someone else — and Sauté’s plea to incoming President Jack B. Critchfield, the 36-year-old chancellor of student affairs at the University of Pittsburgh, was politely rebuffed.

“In attempting to learn as much as I can about your retirement, it appears that the executive committee of the board of trustees, along with President McKean, decided that this action was necessary and that it should be a firm decision,” wrote Critchfield to Sauté. However, the incoming president continued, he hoped that he could count on Sauté’s wisdom and guidance in the coming months.

In academia, it seems, pink slips are often accompanied by plaudits.

Sauté was dismissed with decorum at the May 1969 commencement. McKean read a citation, which surely sounded more like a eulogy to the honoree:

“George Sauté, dedicated professor, concerned citizen, leader in common ventures; as one who has helped lift our vision of world peace, given new directions and dimensions to the education of adults, and helped so many to carry on past their discouragements and even their small hopes; for what you have done and the tradition in which you stand, it is my privilege to bestow upon you as a faithful servant of Rollins, the Rollins Decoration of Honor.”

And so ended a 26-year career at the college. Sauté pioneered the program that would become the Hamilton Holt School, yet his name is little remembered today. His legacy, however, can be seen most nights on campus when classrooms fill with men and women of all ages and backgrounds — many of whom have already spent the day working or caring for children.

Although he was also named professor emeritus, there is no record that George Sauté, dedicated professor, concerned citizen and faithful servant, ever again taught at Rollins.

The School of Creative Arts continued for a while. But it was absorbed in 1982 by the Division of Non-Credit Courses, which was a subsidiary of what had by then been renamed (again) and was known as the School of Continuing Education. After several other iterations, it became today’s Hamilton Holt School in 1987.

A last vestige of the School of Creative Arts, the Summer Day Camp, remained until the plug was pulled in 2015. In an email to the families of campers, Rollins Assistant Vice President Patricia Schoknecht wrote that the program was being canceled “after careful consideration and assessment of resources.”

Ironically, the program was more popular than ever, even with three- and four-week sessions costing $825 to $1,100. “We’re a huge fan of it, and we’re sad to see it go away,” said parent Sally Castro in an Orlando Sentinel story about the closure. “It was unique.” Added parent Susan Godorov, who went to the camp as a child and also sent her daughter: “I feel like a gem in the community has been lost.”

Perhaps the children’s programs were a vestige of an earlier, simpler time. But for many Winter Parkers of a certain age — and for many of their children — the after-school hours spent laughing and learning on a college campus made a profound impact. Even if it sometimes felt like anarchy on Ollie Avenue.