Photography by Rafael Tongol

Photo restoration by Will Setzer at Circle 7 Studio

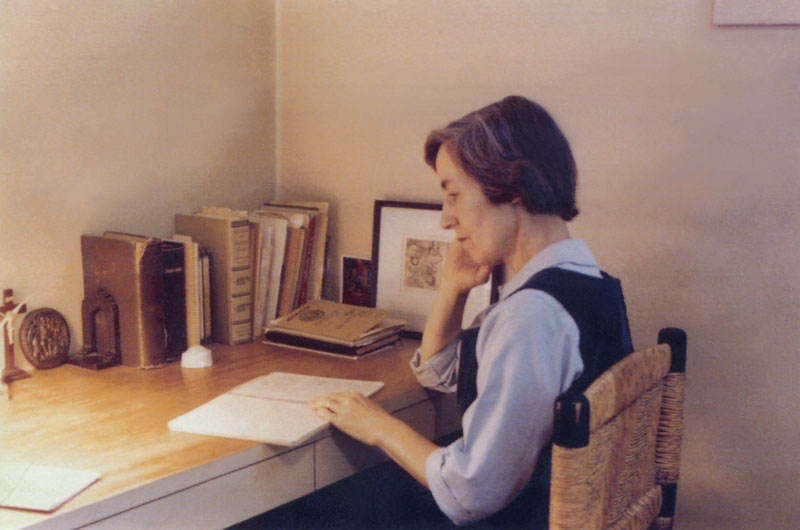

Jerome “Jerry” Donnelly wasn’t raised in the 19th century. But the retired UCF English professor and former Winter Park City Commissioner (1972 to 1980) recalls a childhood home that seemed to exist in a kind of intellectual time warp, where family time involved taking long nature walks and reading to one another aloud. In addition, poets and philosophers occasionally gathered in the library for impromptu salons at which weighty topics were considered.

It sounds comparable, in some ways, to an 1840s home in Concord, Massachusetts, where transcendentalists — Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, Louisa May Alcott — and other unorthodox thinkers gravitated and gathered.

Only it was Ann Arbor, Michigan, where Donnelly, 85, and his two brothers were raised by what he describes as “unconventional parents” who were disinterested in material acquisitions except for a few paintings and thousands of books — many of them modern first editions. They also encouraged their offspring to pursue creative outlets.

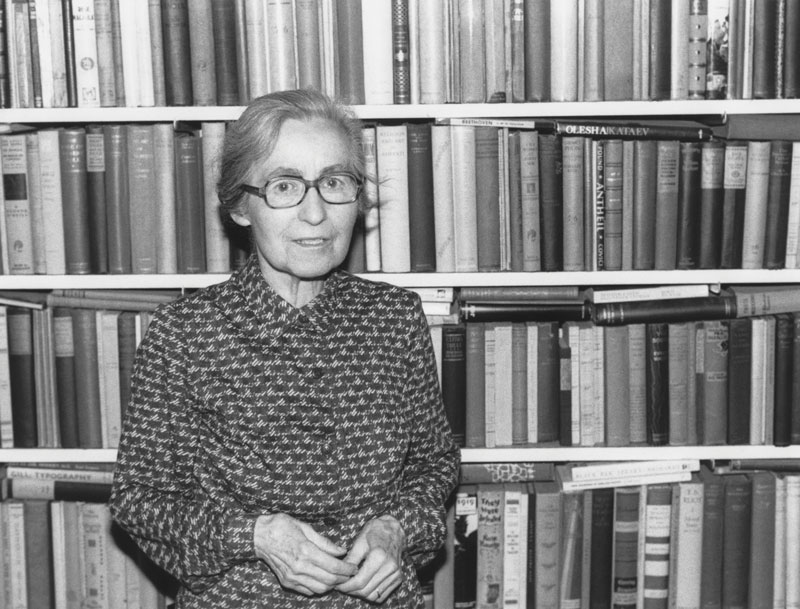

Donnelly’s parents were Walter Donnelly, editor of the University of Michigan Press, and Dorothy Boillotat Donnelly, a poet and essayist who earned recognition and prizes for her published work.

Mrs. Donnelly wrote six well-reviewed books and numerous articles, commentaries and poems for highly regarded “little magazines” — a genre of prestigious but small-circulation periodicals in which writers of new, unusual and often movement-spawning work could get into print.

“I can recall being lulled to sleep by the faint clicking of the typewriter downstairs as my mother typed her first book,” says Donnelly. That book was The Bone and the Star (1944), described by philosopher Mortimer Adler as “a study of primitive man, looked at from the points of view of Christian theology … Mrs. Donnelly has that rare ability which can penetrate myths to the truths they contain.”

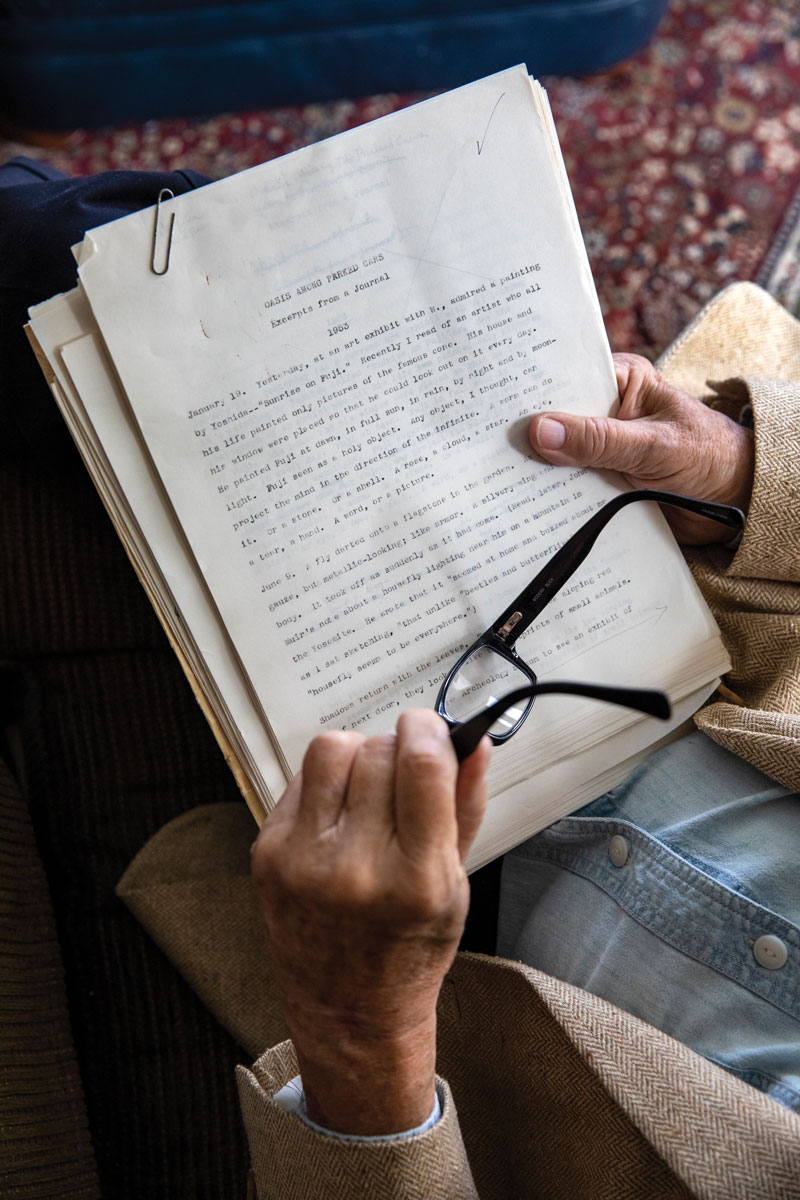

Mrs. Donnelly died in 1994 at the age of 91. And recently her middle son — with the encouragement of his two brothers — undertook the monumental task of going through his mother’s voluminous journals and two “commonplace books” of the sort popular during the Victorian era. Many writers — from Emerson through Auden — used commonplace books to record snippets of information or germs of thought that might be referenced later.

“It gave me a warm feeling going through these old things,” says Donnelly, who remembers that his mother’s fans would sometime show up unannounced but admits to not fully appreciating her work until he was in college at the University of Michigan. “I hadn’t realized that she could be that good.”

Donnelly was struck by a passage from one of his mother’s unpublished essays, which he says “seems to me to be the basis for her poetry.” The excerpt, which discusses how Christians should view the world, reads:

“The Christian consciousness sees all things raised to their highest in their true direction, which is Christward … By means of the Christian consciousness the whole world and all things in it are seen to be a burning bush; everything pulses with the thrill of the electric force of the finger of the Creator, which means that everything, even the ground under our feet, is holy.”

In addition to revelations about his mother’s writing, the exploration of her papers also rekindled in Donnelly fond memories of her reading aloud as the family sat around the dinner table. Although she read many books to her children (and to her husband), the youngsters couldn’t hear enough of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

“In response to requests from my brothers and me, my mother read The Hobbit a number of times over the years — often enough that I could almost recite snatches of it,” Donnelly says.

That a writer with the sensibilities of Mrs. Donnelly would appreciate Tolkien is no surprise since he, like she, was a serious Roman Catholic and his work, like hers, had moral and theological undertones.

Donnelly recalls that his mother once paused when she came to a passage in The Hobbit that describes goblins cracking their whips at the hobbits and dwarves who were their prisoners. The goblins seemed like Nazis, she said — an observation that her son would recall decades later when he wrote an academic paper about Tolkien’s satire of Nazism in The Lord of the Rings. (The article can be read by entering “Nazis in the Shire” in any search engine.)

In contrast to her poetry, most of Mrs. Donnelly’s prose was religious, most notably God and the Apple of His Eye (1973), which she described in the foreword as “a little book of observations and reflections on God and people and what they have to do with one another.” An earlier version of the book, says Donnelly, was to be titled A Letter to My Sons.

Donnelly also remembers the informal salon-like evenings that his parents hosted, although as a child he didn’t appreciate the significance of the luminaries who assembled. Poet Dylan Thomas, for example, spent an evening there, and regular visitors included authors, philosophers and prominent visiting scholars from other universities.

Once, during a raging thunderstorm, the Donnellys welcomed a stranger who had taken refuge on their porch. The young man was Robert Hayden, then a student at the University of Michigan who in the 1970s would serve as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress — a role today known as U.S. Poet Laureate. He would be the first person of color to hold the office.

It was just another day at 612 Lawrence Street, which was surely among Ann Arbor’s most interesting addresses.

• • •

Mrs. Donnelly, a native of Grosse Pointe Park, a comfortable suburb of Detroit, attended the Detroit Teachers College (now Wayne State University) and began teaching school at age 17. She later earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University of Michigan and married Walter Donnelly, then an instructor of rhetoric.

Her acclaim as a writer grew, culminating in 1976, when she was presented with the international Christian Culture Gold Medal at Assumption University (Windsor, Ontario), joining the ranks of such historically significant figures as philosopher Étienne Gilson, media theorist Marshall McLuhan and social activist Dorothy Day. The university’s board of governors cited Mrs. Donnelly as “an integral humanist, an outstanding exponent of Christian ideals.”

But she put family first and took joy in raising sons Stephen, Denis and Jerome. “My mother was a stay-at-home mom and declined repeated teaching opportunities from the university,” says Donnelly, who adds that despite her stature in the literary world, his mother was in other ways a traditional homemaker who prepared meals, did laundry and doted on her children — at times finding poetic inspiration while doing the dishes.

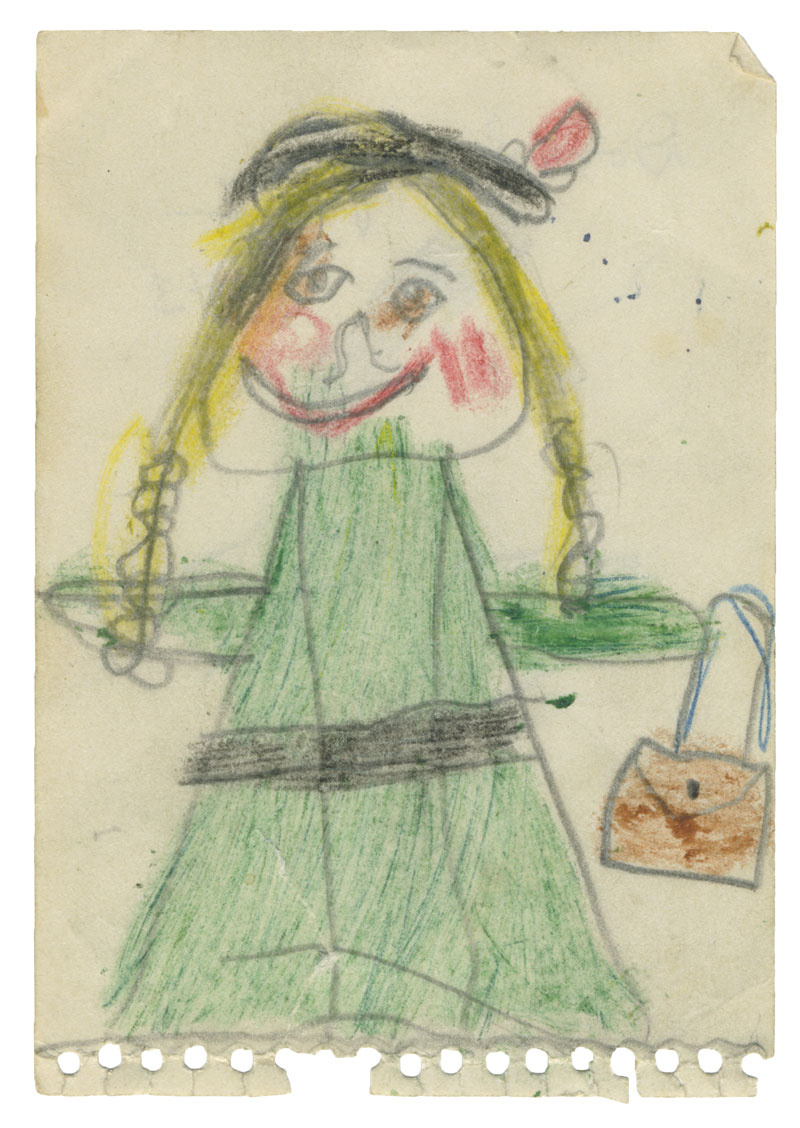

Mrs. Donnelly’s nurturing nature was demonstrated in a special way when her professor-turned-archivist offspring, while sorting through stacks of handwritten journals and other ephemera, found that she had kept one of his childhood drawings scrawled on a tiny piece of note paper — and had immortalized it in a poem.

“My mother encouraged my brothers and me to draw,” says Donnelly. “But I had absolutely no talent for drawing.” Nonetheless, this childhood work of art — created when he was 7 years old — endured and was discovered carefully tucked inside a small envelope.

Measuring three inches in height and two inches in width, it’s a pencil and crayon rendering of a smiling little girl with rosy cheeks and pigtails. She’s wearing a green dress and her arms are thrown open as if reaching out to embrace the world. On an accompanying piece of paper, in Mrs. Donnelly’s handwriting, is the note “Done by Jerry, 1943.”

It’s true that the drawing doesn’t reveal young Jerry to be any sort of artistic prodigy. But something about the image’s exuberance — perhaps it reflected his mother’s humanist worldview and her philosophy about even common things being holy — prompted her to hold onto the drawing and to write a poem about it that was published 15 years later in The New Yorker. The title of the poem is “Drawing of a Little Girl by a Little Boy.”

A hug from mom is always comforting. If it’s true that “everything pulses with the thrill of the electric force of the finger of the Creator,” then it isn’t a stretch to believe that through the rosy-cheeked little girl hidden away for nearly 80 years, Mrs. Donnelly had hugged the son who is working so diligently to preserve her legacy.

DRAWING OF A LITTLE GIRL BY A LITTLE BOY

Suddenly there on the paper air,

all élan, like a Victory-figured prow

blown into view on the prow of a wave,

she balances, arms straight out like a snowman’s;

no hands, no feet, no neck, but a head,

quite ample, and cheeks, very strawberry red.

Everything’s new in his child’s-eye view,

unmuffled by cliché or clue,

like the first school-day and the red letter A

strangle alpha of every readable APPLE,

or the number 1 with its invitation

to follow ad infinitum.

And when SHE appears, formed on a rib

of fancy (the fledgling female seen

in the portrait) the figure of Beatrice lightly

enters his sky; he feels her starry

breath, and is stirred; and greenly, within,

the first little bean-leaf of love.

The “Beatrice” reference is to a character in Dante’s Paradiso, the third and final part of the Divine Comedy. As Dante’s guide through the afterlife, she represents divine revelation, theology, faith, contemplation and grace. Beatrice is thought to have been inspired by a real person, Beatrice Portinari, with whom Dante became infatuated at age 9. She married another man and died at age 25, but continued to be the smitten writer’s muse for as long as he lived. “My mother seems to have used the allusion to suggest that I made the girl in the drawing something similar,” says Donnelly, who believes the image came entirely from his imagination. “The reference to Dante’s Beatrice compliments the little boy, who has made his Beatrice out of love.”