Photo restoration by Will Setzer at Circle 7 Studio

Original photos courtesy of The Rollins College Department of Archives and Special Collections

Many were sorry to see the Fred Stone Theatre at Rollins College demolished in 2018. The creaky little red-brick building near the Harold & Ted Alfond Sports Center made its debut in 1926 as the First Baptist Church of Winter Park and was bought by the college in 1961 after the church outgrew the space.

Of course, it’s always sad when an old building is bulldozed — even out of necessity — and doubly so when that building was named in someone’s honor. But as readers of Winter Park Magazine understand, there’s always a backstory — which we’ll get to shortly.

First you should know that by whatever name, the charming church-turned-theater with its boarded-over lancet windows — a place where both preachers and performers answered their kindred callings — had been deemed a safety hazard due in large part to structural damage from Hurricane Irma in 2017.

Even prior to the storm, however, college officials had determined to replace the venerable venue as soon as possible with a facility more befitting an undergraduate theater and dance program that ranks among the best in the country.

Now, ladies and gentlemen, it’s time to prepare for a premiere. Rollins President Grant H. Cornwell has announced a $3 million grant from the Florida Charities Foundation toward construction of a state-of-the-art performing arts complex — as yet unnamed — located near where the Fred Stone once stood on Chase Avenue.

The building’s size wasn’t finalized at press time, but the Winter Park Planning and Zoning Board had previously approved up to 11,655 square feet. That’s more than four times the size of the Fred Stone — known by college denizens as simply “the Fred,” which seated just 80 people for its often-edgy presentations.

Ironically, the COVID-19 pandemic — the impact of which has made fund-raising an even greater challenge — at first delayed the much-needed project. Ultimately, though, the college’s agile response to this once-in-a-century health crisis impressed Philip Tiedtke, a member of the board of trustees who heads his family’s foundation.

Tiedtke lauded the college’s ability to adapt to unprecedented challenges while remaining true to its liberal arts mission by reconfiguring indoor classrooms, creating outdoor meeting spaces and, in some cases, using a hybrid approach combining virtual and in-person learning.

Such deft management ought to be rewarded, thought Tiedtke, whose giving is usually predicated on problem solving. As a longtime patron of the arts, he didn’t need much time to identify where a targeted donation could have the most immediate impact.

“After the Fred Stone was torn down, you had kids dancing on concrete floors,” he says. “This gift was needs-based and about the quality of education. I said, ‘We have to get these kids into a building, and we have to start it now.’”

The new venue, like the Fred Stone, will offer intimate, experimental productions, many of them student directed. It will also encompass a costume shop and a dance studio. The ornate Annie Russell Theatre, built in 1931 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, will continue to host the college’s mainstage series.

“We’re so grateful to the Florida Charities Foundation and to Philip’s visionary leadership,” says Cornwell. “[The new theater] is critical to the educational excellence and rigor of one of our top-ranked academic programs. Generations of students will benefit from this investment.”

The Tiedtkes have been generous friends to the college — and to the arts in general — for decades. Tiedtke Concert Hall, located within Keene Hall (which houses the college’s music department), is named for Philip’s father, the late John M. Tiedtke, who chaired the board of trustees for the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park for 54 years.

So the foundation’s gift was indeed good news, especially for performing arts students who routinely (and justifiably) complained about Fred Stone, the building. But what should we know about Fred Stone, the man?

FROM VAUDEVILLE TO BROADWAY

The Colorado-born Stone, though little-remembered today, began his career in the 1880s as an acrobat with traveling circuses. He graduated to vaudeville and minstrel shows (unfortunately, his act often involved blackface routines) and later snared starring roles in musical comedies and legitimate theater. In his waning years, he played character roles in motion pictures.

As a stage performer, Stone’s most notable star turn was that of the Scarecrow in the first production of L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz, where his comedic acting chops and acrobatic dancing style won rave reviews through more than 1,300 performances between 1903 and 1907 in touring companies and on Broadway.

He married actress Allene Crater, who had a minor role in Wizard, and eventually the couple had three daughters, all of whom became performers and often shared the stage with their legendary father. The family lived comfortably in Forest Hills, New York, where Stone bought property northwest of his home and built two cottages, a stable, a riding track and a polo field

Stone, together with longtime performing partner David Montgomery, appeared in a series of successful revues throughout the early 1900s. Most were hits in New York first and then went on tour — demonstrating that Stone’s name meant boffo box office in the boondocks as well as on Broadway.

Concurrently, as Stone’s stage successes multiplied, he made a series of undistinguished silent films, none of which appear to have survived. In the early days of the cinema, it seemed, the triple-threat trouper was best appreciated in person. Critics were smitten with Stone’s energy, charisma and versatility — attributes that could elevate sometimes mediocre material.

Vanity Fair’s P.G. Wodehouse declared that “Fred Stone is unique. In a profession where the man who can dance can’t sing and the man who can sing can’t act, he stands alone as one who can do everything.”

And he did, indeed, do everything in stage productions of The Red Mill (1906), The Old Town (1910), The Lady of the Slipper (1912), Chin-Chin (1914), Jack O’Lantern (1917), Tip Top (1920), Stepping Stones (1923), Criss-Cross (1926), Three Cheers (1928), Ripples (1930), Smiling Faces (1931), Jayhawker (1934), Lightnin’ (1938) and a revival of You Can’t Take it With You (1943).

Three Cheers — which costarred daughter Dorothy — was notable because Stone had been sidelined for several months after his small airplane crashed, causing career-threatening injuries. Famed cowboy philosopher Will Rogers filled in for his close friend, who amazed doctors by fully recovering and dancing as energetically as ever upon his return to the stage.

In Ripples, Stone and Dorothy appeared together as Raggedy Andy and Raggedy Ann. This otherwise silly romp is worthy of mention because the music was by Jerome Kern, who would become one of the most important popular music and musical theater composers of the 20th century. His contributions to the Great American Songbook include “Ol’ Man River,” “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” and “The Way You Look Tonight.”

Sinclair Lewis’ Jayhawker — which costarred youngest daughter Carol — marked Stone’s debut as a dramatic actor. He played the lead role, Ace Burnett, a U.S. Senator from Kansas who tries in vain to stop the Civil War. The show ran only three weeks on Broadway and generated tepid notices. Opined Variety: “[Stone] impresses rather pleasantly and it seems a shame to have wasted his talents thus.”

Lightnin’, a revival of a 1918 musical comedy about “Lightnin’” Bill Jones, a carousing lawyer whose wife runs a seedy hotel that straddles the border of California and Nevada, was described by Variety as “dated and a creaky mixture of crude melodrama.” But the same review praised Stone, describing him as “something of a theater tradition who brought enthusiastic and friendly applause.”

George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s You Can’t Take It With You is familiar to modern audiences and remains widely performed. Stone starred as Martin “Grandpa” Vanderhof — played by Lionel Barrymore in the 1938 film adaptation — the curmudgeonly patriarch of a zany extended family. The revival played to packed houses and warm reviews.

Stone would reprise the role twice — once at Rollins for a 1946 fundraiser and once four years later, near the end of his career, for the Las Palmas Theatre in Los Angeles.

QUITE A CHARACTER (ACTOR)

In his 60s and too old for acrobatic dancing, Stone bought a home in Hollywood and began to pursue opportunities for character roles in films. Prospects seemed promising when he was cast as Katharine Hepburn’s sickly father, Virgil Adams, in RKO’s Alice Adams (1936). To everyone’s surprise and relief, the prickly Hepburn treated Stone with the respect due a show business veteran, and the two became fast friends.

But the triumphant premiere for Alice Adams at Radio City Music Hall was overshadowed for Stone when he received word the following day that Will Rogers had been killed in a plane crash. At a private funeral in Hollywood Hills and a public memorial service held at the Hollywood Bowl, a grieving Stone sobbed openly and had to be physically supported by his wife and daughters as they walked to their seats.

Almost immediately, though, Stone was back at work in Paramount’s The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (1936) — only the second feature film to be shot in Technicolor. It followed the travails of rustic Kentuckians battling railroad and mining interests.

Adapted from a bestselling 1908 novel by John Fox Jr., The Trail of the Lonesome Pine starred Henry Fonda in one of his first film roles and was another financial and critical success. Stone believed that he had found a niche playing sympathetic rural characters and hoped to solidify his post-stage career in westerns — a genre for which he seemed well suited.

As a film actor, Stone was certainly busy in 1936, appearing in several bargain-basement RKO releases. But he quickly grew to dislike the studio, which was notorious for its skimpy budgets and hurried production schedules.

That summer, Stone returned to Paramount to make My American Wife, where his performance as Ann Sothern’s grandfather prompted The New York Times to acknowledge that the old barnstormer “had suffered plenty with his recent assignments but gets a much better chance here to show what he can do. When he is not present on screen, he is missed.”

After making several forgettable B-movies for Warner Brothers, Stone finally got his western — and it was a mighty good one. In the Samuel Goldwyn Company’s The Westerner (1940), Stone received third billing behind Gary Cooper and Walter Brennan.

The film, directed by William Wyler, earned an Oscar for Brennan, who played corrupt Judge Roy Bean, and Oscar nominations for Best Original Story and Best Art Direction. Stone, in what would be his final screen role, played a homesteader struggling against Bean and his cattle-ranching allies.

VICTOR HUGO OF THE NORTH

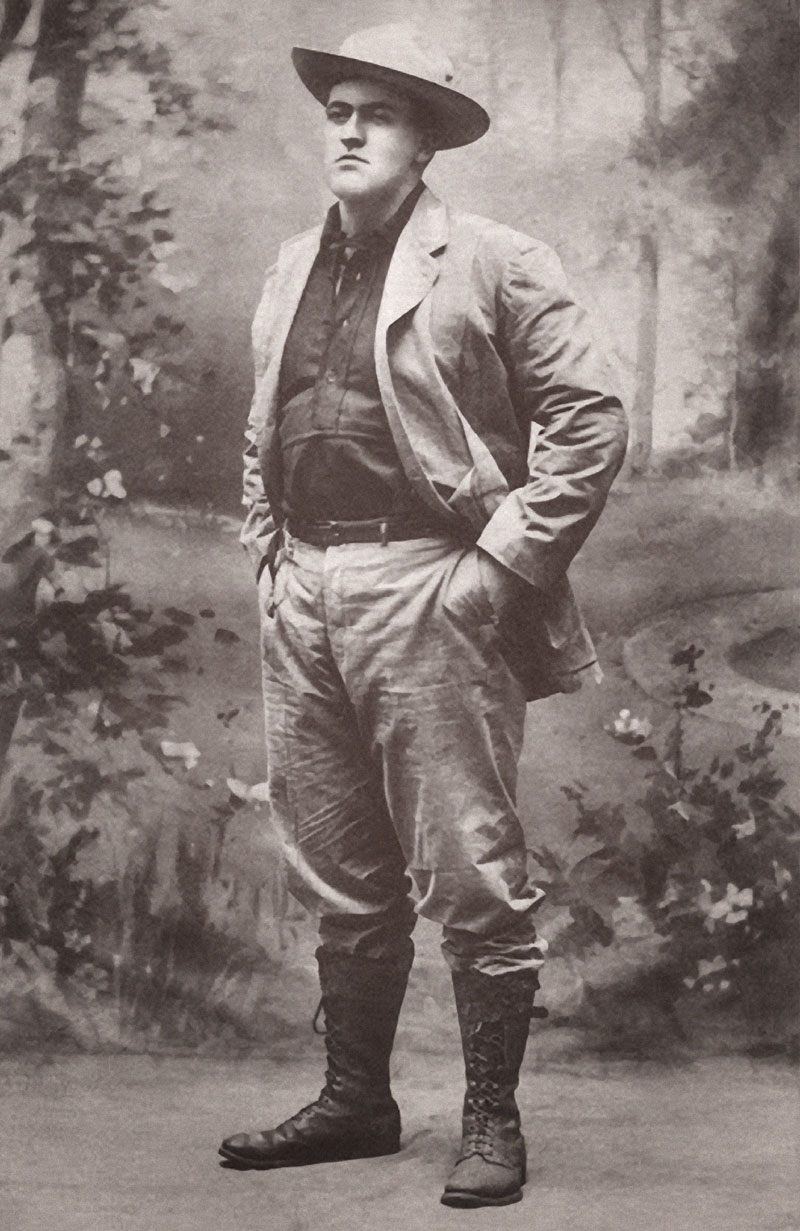

Stone’s Rollins connection was through his brother-in-law, novelist Rex Beach, who was married to Allene’s older sister, Edith. The hard-living Beach, who attended the college from 1891 to 1896 but failed to graduate, was nonetheless regarded as an important alumnus.

He had traveled to Alaska in 1900 during the gold rush but didn’t strike it rich — at least not from prospecting. He did, however, mine numerous colorful tales, and in 1906 wrote a bestselling novel, The Spoilers, based upon a true story of corrupt government officials seizing gold mines through fraudulent means.

The Spoilers — which was described by one critic as “throbbing with the blood-blindness of ferocity” — was adapted as a stage play and was filmed five times with versions starring Gary Cooper (1930), John Wayne (1943) and Jeff Chandler (1955).

The prolific Beach, sometimes called “the Victor Hugo of the North,” wrote countless short stories and several dozen adventure novels. All sold well early in the 20th century and several, in addition to The Spoilers, were adapted for the screen.

Literary sorts never cared for Beach, which neither bothered the writer nor impacted his bank account. One reviewer described his work in general as “big, hairy stories about big, hairy men” while others criticized his formulaic approach to storytelling. His readers, not surprisingly, tended to be young men who hung on his every word.

Beach and Stone shared a proclivity for macho thrill-seeking and took at least one trip together to Alaska for a bear hunt. They remained lifelong friends, except for a two-year period when they were estranged over a rift about boxing and bigotry.

Stone sometimes sparred with his friend and neighbor “Gentleman” Jim Corbett, a former World Heavyweight Champion who had become a vaudevillian following his retirement from the ring.

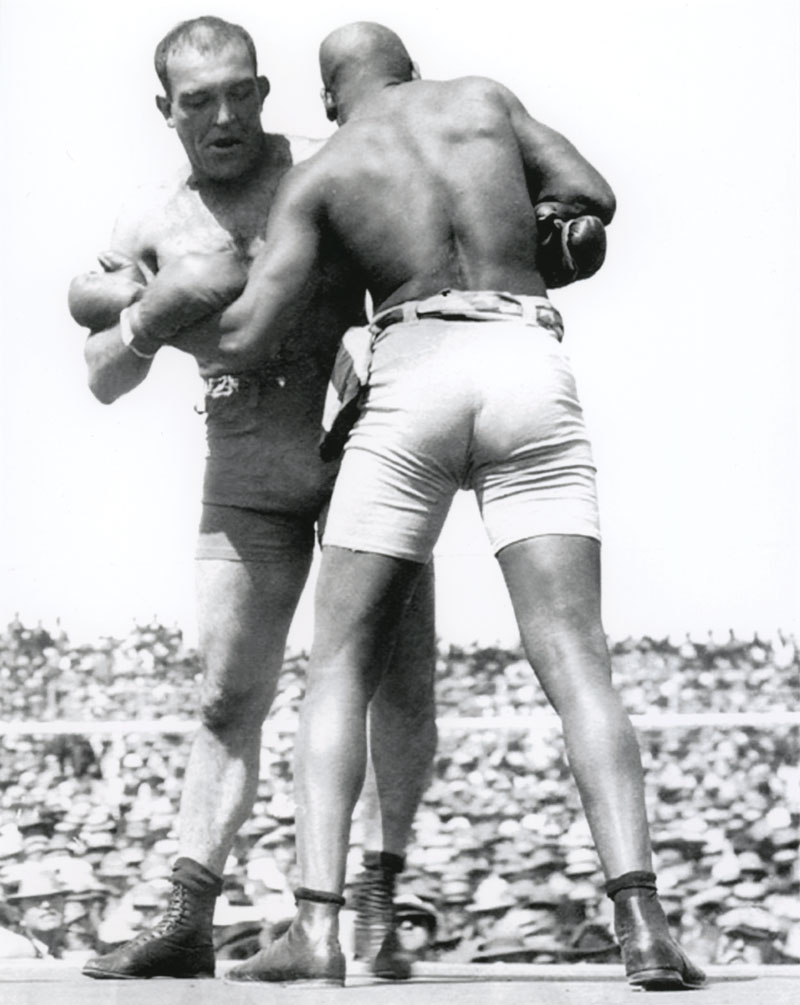

Corbett told Stone that Beach and writer Jack London had helped facilitate an upcoming prize fight between champion Jack Johnson, an African American, and former champion Jim Jeffries, an overweight alcoholic who had not stepped into a boxing ring for five years.

Beach, like many white boxing aficionados of the era, was horrified that the cherished championship belt was held by a “dreaded negro” and believed that even a dissolute Jeffries could defeat the usurper and reclaim the title for its “rightful owners.”

Stone — who feared that the fight would be a fiasco and was offended by the hateful rationale behind it — confronted his brother-in-law about what he had heard from Corbett. When Beach confirmed that he and London had indeed helped recruit Jeffries to face Johnson, and the reasons why they had done so, Stone was horrified. He vowed never again to speak to Beach.

Johnson handily won the match in 1910 and sisters Allene and Edith, after two frosty years, finally negotiated a reconciliation between their feuding husbands.

From a modern perspective, it seems discordant that Stone, who performed in blackface and routinely exploited racial tropes, took such umbrage at Beach’s beliefs, which were, sadly, not uncommon at the time. But Stone surely knew and shared stages with the handful of African American entertainers who were popular enough to perform on the mainstream vaudeville circuit.

We know, for example, that Stone admired Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, who caused a sensation with an intricate “stair dance” in which he tapped his way up and down a small staircase. Robinson tried to secure a patent on the choreography, but when that effort failed, other dancers — Stone included — learned the routine and performed it with impunity. Only Stone, however, sent Robinson a check — a quiet gesture of respect from one great hoofer to another.

As for Beach, perhaps the thrashing that Johnson administered to Jeffries caused him to reconsider his position. More likely, though, Stone and Beach simply agreed to disagree for the sake of family harmony.

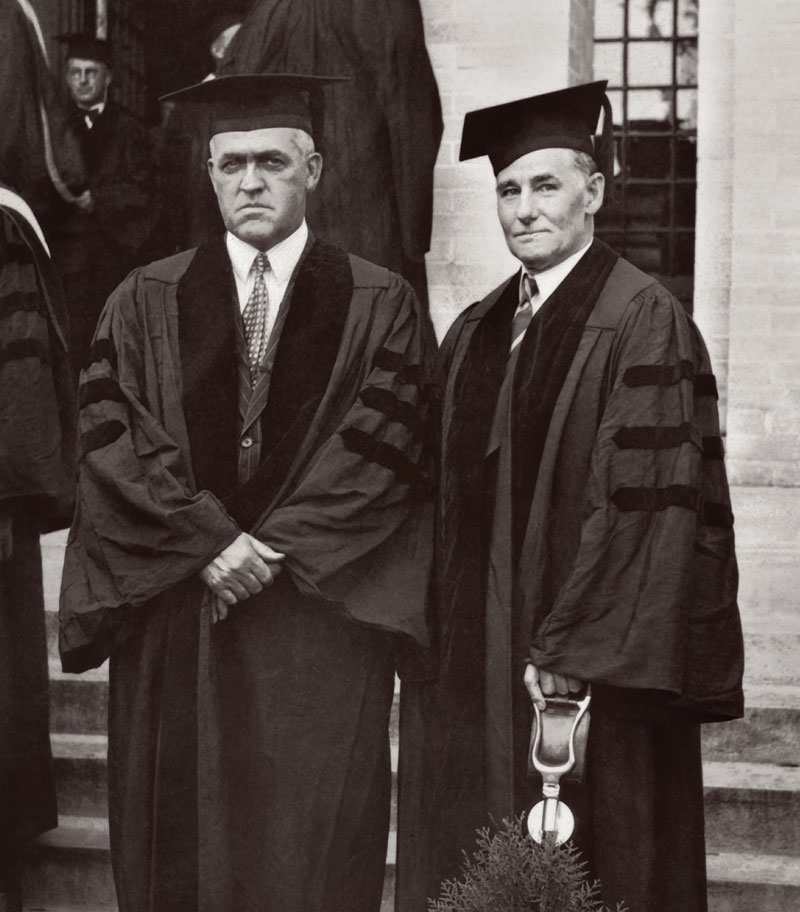

It was Beach, in fact, who lured Stone to Rollins in 1929. The actor, just a year removed from his potentially catastrophic and widely publicized airplane crash, had made a triumphant comeback and was on tour with daughter Dorothy in Three Cheers when he visited the campus.

There, to Stone’s great surprise, he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Literature (Litt.D) by President Hamilton Holt, who had doggedly pursued Will Rogers for that year’s honor but settled for Rogers’ less famous but equally worthy friend — a circumstance surely unknown to the honoree.

Beach took the pulpit at Knowles Memorial Chapel and described Stone as “probably the best-loved figure on the American stage, who has brought more mirth to the hearts of the theatergoing public than any man before the footlights. He makes them laugh, but the tear is not far behind the smile.”

Stone showed his appreciation to Rollins in 1939, when he returned for a week’s run as the director and star of Lightnin’ to raise funds for the Fred Stone Laboratory (later the Fred Stone Theatre). The project involved adding a stage to Comstock Cottage, a wood frame house at the corner of Fairbanks and Chase avenues that had previously been a dormitory for the Chi Omega sorority.

Within the rambling structure, workshops, classes and performances were held for 34 years until it was deemed a fire hazard and demolished in 1973. Before the dust had settled, an erstwhile Baptist Church — by then known as Bingham Hall and used for faculty gatherings — was retrofitted as a theater and inherited Stone’s moniker and mission.

(The versatile building — named for Mortimer Bingham, a charter member of the board of trustees — had been purchased by the college in 1961 but remained at the corner of Comstock and Interlachen avenues until in 1965, when it was moved on campus to Chase Avenue.)

Stone, who never attended college, was back at the place he affectionately referred to as “my alma mater” in 1946 to appear in and direct You Can’t Take It With You, in which he reprised his role as Martin “Grandpa” Vanderhof, and again in 1947 to appear in and direct Mark Twain by Harold M. Sherman, who had also written the screenplay for the tear-jerking 1944 Warner Brothers biopic The Adventures of Mark Twain.

Both shows, held at the Annie Russell Theatre and co-starring members of the Rollins College Players, were fundraisers for the drama department. The Orlando Sentinel praised Stone’s performance in Mark Twain as “uncanny” and noted how much the actor looked like the irascible humorist when costumed in a white wig and walrus mustache.

Naturally, Holt persuaded Stone to appear at the Animated Magazine during his 1939, 1946 and 1947 sojourns to Winter Park. As most Winter Parkers know, the Animated Magazine was the brainchild of Holt and Professor of Books Edwin Osgood Grover, who annually assembled prominent speakers from the fields of literature, business, academia and politics for an event that drew thousands to the campus.

TAKING THEIR FINAL BOWS

Stone’s last years were heartbreaking. He began to lose his vision to glaucoma, developed dementia and suffered a near-fatal heart attack in 1955. When Allene died in 1957, his daughters opted not to tell him. Indeed, his condition had deteriorated to the point that he often ceased to recognize her anyway. Declared “the Grand Old Man of the theater” by The New York Times, Stone died at his Hollywood home in 1959 at age 85. The following year, his work in theater and film earned him a place on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

During Stone’s sad decline, one of his few visitors other than immediate family members was his cousin, a former song-and-dance man who had more recently achieved fame for his portrayal of “Doc” on the CBS western series Gunsmoke. In a fitting coincidence, Milburn Stone, accompanied by co-star Amanda Blake (“Miss Kitty”), visited Rollins just a month after Fred’s death. The duo lent star power to the local CBS affiliate’s cerebral palsy telethon and answered student questions at the Annie Russell Theatre.

Stone’s friend Beach also suffered in his final years. He and Edith had settled near the Highlands County city of Sebring on substantial acreage, where Beach eased his frenetic writing pace and turned his attention to experimental farming.

But Edith died in 1947 and Beach was diagnosed with throat cancer shortly thereafter. He took his own life in 1949, at age 72, because pain from the disease had become so severe. Rollins accepted his ashes, along with his wife’s, and had them buried near the Alumni House on campus. Rex Beach Hall, a dormitory, was erected in his memory.

So, as broadcaster Paul Harvey once intoned, now you know the rest of the story. And you may be wondering if the new theater will carry Stone’s name. A spokesperson for the college said no decision had yet been made, but that Stone would be recognized in some way.

As well he should be, perhaps with a lobby display using items from the Betty M. Mitchell Collection of Fred Stone Theatrical Materials at the college’s department of archives and special collections. Mitchell was a neighbor of Charles Collins, husband of Carol Stone, and the collection was donated by her daughter, Joyce.

After all, while not a household name today, Fred Stone was, according to Beach, as stellar a human being as he was a performer.“To my way of thinking,” said Beach at the ceremony awarding his friend an honorary doctorate, “the biggest thing about Fred is not his genius as an entertainer and his hold upon the affections of the American public, nor is it the fact that, in spite of his enormous success, he made good with but few advantages; it is the fact that, in spite of his enormous success, he has remained a simple, unspoiled, honest and charitable man.”