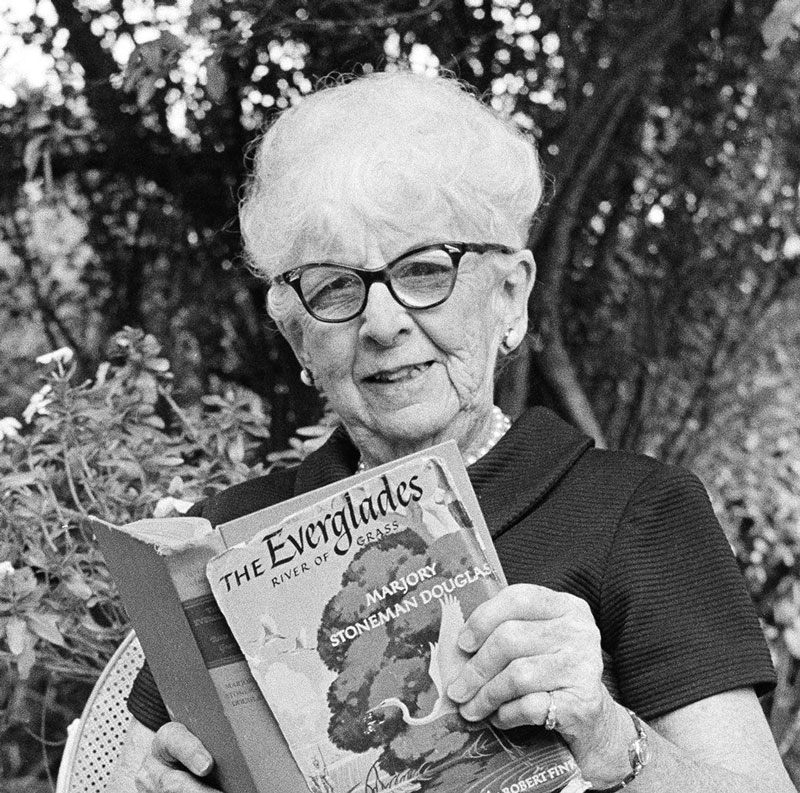

When Marjory Stoneman Douglas, born and raised in Minneapolis, was 4 years old, her family visited Tampa. There, boosted aloft, she delightedly picked an orange from a tree in the garden of their hotel. And the rest is Florida history.

Literary license tempts us to draw a straight line from that early harvest to Douglas’ later migration to Florida, her blossoming as a crusading conservationist and her epic ode to the Everglades, River of Grass, published in 1947.

The line has since become a baton passed to an army of Douglas disciples in the race to preserve and protect “the land of flowers” from deflowering by what some call progress.

“The Grand Dame of the Everglades,” who died in 1998 at age 108, is survived not only by her beloved river — which was considered merely a swamp prior to her scholarly yet readable bestseller — but by legions of citizens inspired to sustain the cause through their own activism and writing.

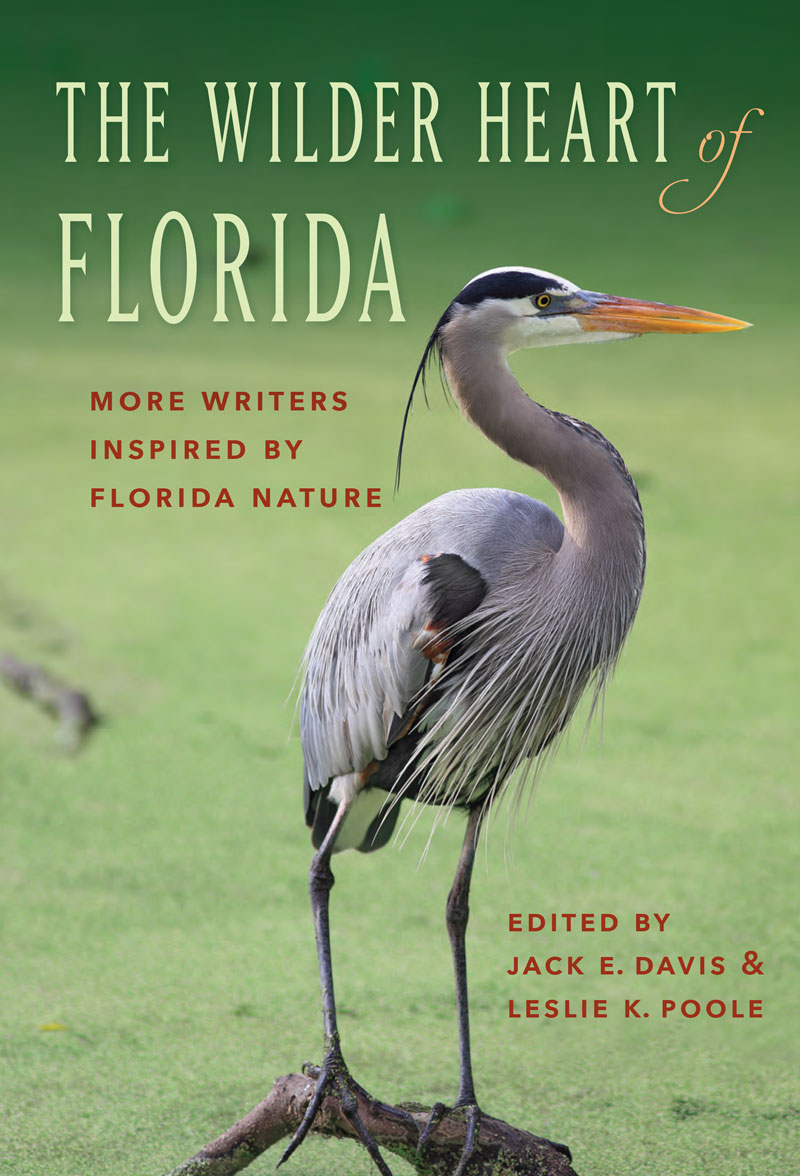

A sampling of outstanding essays about the state’s persistently threatened environment — and even some poetry — have been collected in The Wilder Heart of Florida: More Writers Inspired by Florida Nature, published by the University of Florida Press in March. It’s a sequel to The Wild Heart of Florida, which was released 20 years ago.

Royalties from book sales will go to The Nature Conservancy’s Florida Chapter, which owns and manages approximately 55,159 acres in the state including four preserves that are open to the public: Apalachicola Bluffs & Ravines in Liberty County, Blowing Rocks Preserve in Martin County, the Disney Wilderness Preserve in Osceola County and Tiger Creek Preserve in Polk County.

In their introduction to Wilder Heart, editors Jack E. Davis, a professor of history at the University of Florida and a Pulitzer Prize winner for The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea; and Leslie K. Poole, an assistant professor of environmental studies at Rollins College and a Pulitzer Prize nominee for environmental writing at the Orlando Sentinel, offer a rather bleak outlook:

“With the dawn of each day, Floridians awaken to a rapidly diminishing future for the state’s unique and glorious natural systems. As the bulldozers rev up, cars enter highways and construction cranes begin to swing, our wild spaces become more precious and threatened. The loss is not only habitat for flora and fauna, but also reflects a darkening of the state’s soul — a place built on the idea of finding Eden, health and beauty. What better way to understand and acknowledge the magnitude of such losses than to celebrate our wildest treasures?”

And celebrate the writers do — even if some of them consider the festivities more akin to a wake. The 26 essays and eight poems in Wilder Heart are organized in six chapters with titles that, when read aloud, sound like a mini haiku about Florida: “Beckonings,” “Revelations,” “Animals,” “Water,” “Terra Firma” and “At the Heart.”

The book’s roster of contributors includes academicians, poets, activists, a birder, a veterinarian, a fisherman, an artist, a journalist, a gator hunter, a tribal chief, a citrus grower, a civil engineer, an environmental lawyer and a river guide.

Essays by legends such as Douglas and Harriet Beecher Stowe, (Uncle Tom’s Cabin) are also included. Douglas’ chapter, “Excerpts from the Gallery,” is curated from a daily column she wrote for the Miami Herald, where her father was editor in chief, in 1923. The short pieces presage her later activism.

“Look out your window,” Douglas writes. “Can you see a pine tree? If you can, you’re lucky. They are going fast. And every day somebody cuts down a few more to make a new subdivision that, without them, will be as raw and ugly as plain dirt without trees can be. Do you own a pine tree? Then you are lucky. But if you appreciate it, you are more than that. You have a genuine eye for beauty, which is another word for spiritual common-sense.”

Stowe’s “Up the Ocklawaha: A Sail into Fairy-Land,” from 1873, was originally published in the Christian Union. The New England-born author and abolitionist — who had moved to Mandarin, near Jacksonville, and bought a small citrus farm — recounts a seemingly mystical journey along the river aboard a tiny steamer en route to Silver Springs.

“Growth seemed to have run riot here, to have broken into strange goblin forms, such as [19th century illustrator Gustave] Doré might have chosen for his weird imagining,” Stowe writes. “Here, where foraged nature has been let alone, where the fiery heat and the moist soil have conspired together, there is a netting and convoluting, a twisting and weaving and intertwining of all sorts of growths; and one might fancy it an enchanted forest, where the trees were going to change into something new and unheard of.”

Wilder Heart, which is rich in history and deep in science and expertise, nonetheless maintains a tone of wide-eyed wonder and sensuous delight — directed straight at the wild heart that beats within many Floridians. And we do mean wild.

The collection begins with a macabre poem, “Seduction in Key West,” by Orlando poet laureate Susan Lilley, and ends with a witty but revelatory essay, “Florida is a Pretty Girl,” by fiction writer Frances Susanna Nevill, who compares the state to an attractive woman who is constantly set upon by greedy users. Everything in between is, in its own way, just as compelling.

“Our most pressing challenge is to find ways to connect the dots between hearts and minds,” Temperince Morgan, executive director of The Nature Conservancy, writes in the foreword of Wilder Heart. “Anyone who has spent time here can’t help but fall under the spell of our weird, wild state.”

Winter Park is represented in the eclectic assortment of contributors by a quintet of authors, all of whom have ties to Rollins College: Poole, Bruce Stephenson and Claire Strom are professors, while Gabbie Buendia was a valedictorian in the Class of 2019. Lilley was an instructor in the college’s English department and now teaches literature at Trinity Preparatory School.

Each can point to a moment or a memory that initiated their enduring psychic bond to Florida. For Buendia, it was a reluctant, fretful first hike at age 17 in the Econ wilderness while wearing cheerleader practice gear. For Lilley, it was a childhood of falling asleep at night and awakening in the morning to the beauty of Lake Sue, just outside her window.

For Strom it was flying from North Dakota to Orlando for a job interview and marveling at the stunning abundance of water — ocean, lakes, lagoons, rivers, ponds — she saw from her window seat.

And for Stephenson, it was seeing tranquil and orderly Winter Park for the first time, on a bus ride with the Merritt Island Mustangs high school basketball team for an away game against the formidable Winter Park Wildcats.

‘THEY’RE KILLING THE GOOSE THAT LAID THE GOLDEN EGG’

For Poole, 63, a Florida kid blithely immersed in nature’s blessings, her path was set as a result of doing journalism about preservationists. Telling their stories and describing their causes opened her eyes to the incalculable value and fragility of her environment.

Poole grew up in Tampa. Her mother’s family grew oranges in Micanopy, south of Gainesville, until the Great Freeze of 1894-95; her father came from a line of family farmers in Live Oak. But little Leslie seemed determined to prove that being outdoorsy wasn’t hereditary.

“I was never what you’d call a nature girl,” admits Poole, who says her mother often had to chase her out of the house. She rode her bike for hours and explored the woods, forming an unconscious bond with the outdoors.

“In high school I’d go out to remote lakes with friends and go skiing — that was sort of my social group,” she says. “It was a safe, serene place. When I got older, I came to realize how much of that world had disappeared. As a teenager, you don’t think about that.”

These days, however, Poole makes certain that her students in environmental studies do think about that. Taking an approach not unlike her mother’s, she chases her students out of the classroom and shows them what she’s so passionate about — and what they’re on the verge of losing unless they’re vigilant.

“My class is all about field trips,” she says. “My students aren’t there to make a fortune; they’re there to change the world. I want them to see the beauty and smell the blossoms and see the wildlife. I took them to Lake Russell [in Osceola County] and had them put their hands in the lake and realize that the water is headed for the Everglades.”

Sometimes, the field trips are nearby. Poole has walked classes — often including many freshmen from out of state — to Mead Botanical Garden, which is open to the public, and the Genius Preserve, which is private property owned by the Elizabeth Morse Genius Foundation. Both are just minutes from campus.

On one outing to the Genius property, students were awed by the sight of trees laden with oranges — not a typical sight in the Northeast or the Midwest — and were permitted to pluck a few star fruit from a Carambola tree. “When I was growing up it was no big deal,” Poole says. “For these kids it was so exciting.”

The aha! moment for Poole came in the late 1980s when she was a journalist with the Orlando Sentinel working on “Florida’s Shame,” series of investigative stories on unfettered growth in Central Florida. Jane Healy, then the paper’s associate editor, won a Pulitzer Prize for a series of editorials related to the series, while Poole was a nominee for her reporting.

Florida’s Shame caused considerable consternation in the development community, resulting in an estimated $500,000 worth of canceled advertising schedules from builders. Says Poole: “Importantly, the series pushed the state to adopt tougher growth management regulations. Which [Governor] Rick Scott gutted. But that’s another story.”

Indeed, it’s the never-ending story, and struggle, that’s become Poole’s life. Like her students, she wants to change the world mostly by keeping it the same — protected from the ravages of modernity and commercialism. Hard political reality, however, has made her a realist.

“That’s the truth about Florida — indeed about the world — today. Few unspoiled spots of nature exist,” she writes in her Wilder Heart essay, “Woodpeckers and Wildness.” Consequently, Poole gains satisfaction from small but significant victories, and recounts one in Wilder Heart — the resurgence of the nearly extinct red-cockaded woodpecker at the Disney Wilderness Preserve.

But she celebrates a victory in the book — the resurgence of the nearly extinct red-cockaded woodpecker (right) at the Disney Wilderness Preserve. The preserve, writes Poole, is an 11,500-acre oasis “at the edge of Central Florida’s suburban chaos.” But she credits the theme park with creating and funding the preserve, which is run by

The Nature Conservancy.

The preserve, writes Poole, is an 11,500-acre oasis “at the edge of Central Florida’s suburban chaos.” Disney and the theme parks, she continues, “are the engines that turned the rural citrus-growing region into a traffic and development nightmare, displacing wildlife, wetlands and forests.”

Yet it was also Disney, Poole adds, that led the way in creating and funding the preserve — run by The Nature Conservancy — “setting an example of how collaboration between diverse partners can create something ‘wild’ in a place where nature is slowly vanishing. Ah, the irony. But ahhhh, the wonderful result.”

Poole is also a champion of the leadership roles women have historically played in Florida’s environmental battles. In her 2015 book, Saving Florida: Women’s Fight for the Environment in the Twentieth Century, Poole salutes these women and details their struggles and triumphs. She also teaches a course called “The Three Marjories” that explores the work of Douglas, author Marjory Kinnan Rawlings (Cross Creek) and scientist Marjorie Harris Carr.

Carr, the least well-known of the trio, helped write one of the first environmental impact statements in support of a lawsuit brought by Florida Defenders of the Environment (which she co-founded) and the New York-based Environmental Defense Fund. The groups were aligned against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and its ill-fated Cross Florida Barge Canal on the Ocklawaha River ecosystem.

The canal was eventually decommissioned, thanks in no small part to Carr. And yes, Poole is aware that Douglas spelled her name “Marjory,” rendering the title of her course not strictly correct. And yes, she’s aware that Rawlings — unlike Douglas and Carr — was a writer of fiction and autobiography, not an environmental crusader.

Still, the fact that these three women — whose names were pronounced in the same way, at least — were three of the most consequential figures in the history of Florida environmentalism is remarkable, to say the least.

And speaking of women, did you know that it was a coalition of women’s clubs that lobbied for legislation to establish Florida’s first state park, Royal Palm Park, which was later the nucleus of Everglades National Park? That was in 1916 — before club members even had the right to vote. Their activities are also chronicled in Saving Florida.

Adds Poole: “When I’m asked, “What can I do?’, I say, ‘Register to vote.’ It’s clear that the environment is a political animal. You’ve got to be involved in politics. I’ve seen an awful lot of willful ignorance from the State Legislature, refusing to act. I hate to use the cliché, but they’re killing the goose that laid the golden egg.”

‘IF I CAN GET TO THE RIVER, I CAN FIND MY WAY BACK’

Gabbie Buendia’s essay, “The River That Raised Me,” could have been subtitled, “How a Type-A Personality Found Happiness in the Wild.” Her family emigrated to Florida from the Philippines when she was 2 years old. Buendia grew up in Casselberry and rarely ventured into the family home’s backyard.

“I didn’t really have a connection with nature when I was a kid,” she says. “I was fearful for the most part of the other life out there, like animals. One time I tried to do the camping thing. I wasn’t very prepared, and it was a cold night. I was like, ‘I don’t think I like this.’”

Instead, Buendia was laser-focused on a path to excellence at Lyman High School. She was a cheerleader and valedictorian of her class whose environmental activism was limited to swearing off use of disposable plastic water bottles.

“My perceptions of how to enjoy natural spaces and what kind of people enjoyed them were greatly misinformed,” Buendia writes in her Wilder Hearts essay. “They were influenced by limited access to positive environmental experiences growing up and a lack of representation of people of color in the outdoor spaces and activities that I did have the chance to participate in.”

Molten impressions might have hardened to stubborn beliefs if Buendia hadn’t warily accepted an invitation from a friend named Amy to boldly go where she never wanted to go: the wilderness, on a hike. “I didn’t know what to do and what to bring,” she writes. For her inaugural walk on the wild side, Buendia wore her cheerleading practice gear and an old pair of Nikes.

The expedition was through the confusingly named Little Big Econ State Forest, located near Geneva in rural Seminole County. The moniker is a combination of the Little Econlockhatchee River and the larger Econlockhatchee River, which meet just south of the forest.

Despite a few harrowing moments, the hike was ultimately transforming. Initially, though, Buendia treated the ground as a minefield, cautiously remaining a few steps behind Amy.

“I hesitated to follow when [Amy] climbed trees for a better view or when she headed toward more challenging paths,” Buendia writes. “At one point, a snake appeared on the path and caused me so much anxiety that we could not continue until Amy put me on her back and jumped over it.”

Those don’t sound like the words of a born explorer but Buendia returned, again and again, “to take a walk or to write, to do my homework, to talk out loud. I came to the river to cry my eyes out, and I came to the river whenever I didn’t know where to go,” she writes. That first hike, at age 17, “reframed my perceptions and understanding of natural spaces and where I fit into it all.”

At Rollins, Buendia majored in environmental studies, got involved with “green” organizations and delved deeper into exploring preserved land.

Once during finals week, she had spare time before a test and decided to make the most of it by tromping through the Econlockhatchee Sandhills Conservation Area — 706 acres of pine forests, oak hammocks and open scrub near the town of Christmas in east Orange County.

“I arrived just as the morning dew was beginning to sparkle and evaporate off the saw palmetto and gopher apple shrubs,” she writes. After a while, however, Buendia realized she was lost in paradise — and so was her phone’s GPS.

“I had only 40 minutes to orient myself and get my butt to class,” she writes. “Looking up from my watch, I observed the flat landscape of unending sand, grass and trees. I knew I just needed to start moving … and I whispered to myself, ‘If I can just get to the river, I can find my way back.’”

She eventually made her way to the Econlockhatchee and later back to campus “with muddy shoes, a new story” and an exhilarating epiphany about the value of “how beautiful a little disorder and chaos can be.”

Buendia’s honors thesis was entitled Earth Mommas: The Impact of Mothers on the Environmental Justice Movement, which was the culmination of eight months researching how women — specifically mothers — play a unique and instrumental role in leading movements to protect the environment.

Shortly before graduating from Rollins in 2019, Buendia notched another milestone: becoming a U.S. citizen. Then, after graduation, she became an environmental activist through an internship with the Doris Duke Conservation Scholars Program at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

A river runs through her now. She writes: “The river taught me patience, exploration, flexibility — the courage to embrace discomfort.”

‘IN A NETHERWORLD BETWEEN CELEBRATION AND LOSS’

Susan Lilley’s poem “Seduction in Key West” raises the question: If plants have feelings, is one of them rage? Can vegetation exact revenge — revenge more satisfying than the swamp’s passive-aggressive reclaiming of early human settlements?

“Seduction” starts out as a tone poem to the boozy, diaphanous travel-poster Key West of “white-lattice cafes with their fragrant garlic and Key Lime daiquiris” where a cruise ship “opens its maw like a great white shark and expels the tourists onto dizzy Duval Street” in search of “conch fritters, salty edged tequila and clattering shell necklaces.”

But it soon descends into something darker about “steel-hearted pirates and Spaniards seeking gold” and how Seminoles and Calusas lashed the invaders to the deadly green manchineel apple tree and “let the tree’s poison sap eat slowly through the clothing to the skin, to the bones beneath.”

There are likely no colorful postcards depicting that in souvenir shops. Lilley learned about the manchineel apple tree on a guided tour of the small islands around Key West conducted by a marine geologist. She says: “It captured my imagination more than the Pirate Torture Museum.”

Born in Lake County, Lilley, 67, grew up in Winter Park in her family’s home on Lake Sue. “I remember waking up every day and seeing the lake and the cypress trees,” she says. “The last thing I saw at night were lights blinking across the lake. It was a comforting, mysterious body of water. It really had an effect on my imagination.”

Lilley was a late-blooming poet, publishing her first collection, Night Windows, at age 52 in 2006. She’d always had the urge but lacked the chutzpah to write seriously. “I thought, ‘There’s so much good poetry out there. Why mine?’” She followed her debut with Satellite Beach (2012) and Venus in Retrograde (2019).

“When I was a child my grandmother lived in a big citrus area,” she says. “I remember spending Christmas at her place, and on cold nights you could smell the orange refineries. It smelled like cake. Groves covered the countryside — it was such a gorgeous sight from the road. Now it’s completely gone. It was so visual and sensual; you could smell the blossoms in the spring. Oh, my god.”

Lilly worries about the environment that shaped her sensibility. “I can’t help but swoon over the beauty — but it’s heartbreaking to see the swallowing up of majestic places that can’t be replaced. It feels like we’re in a netherworld between celebration and loss.”

What’s a poet to do? In “Seduction,” Lilley imagines a modern-day tourist venturing out without a guide to a small island where “in a dim circle of a forgotten world, this lonely tree waits and spreads its bright green danger.”

Is the poem a revenge fantasy — poetic justice on behalf of a Florida environment violated by intruders seeking gold? It’s not polite to ask poets such direct questions. But it’s no stretch to read “Seduction in Key West” not just as a cautionary tale for today, but the earliest recorded case of Stand Your Ground.

‘BUT MOST OF ALL, I MARVELED AT THE WATER’

Claire Strom, professor of history at Rollins, arrived here by way of two places that are environmental opposites of Central Florida: North Dakota, arid and cold; and Cambridge, England, tidy and manicured for centuries.

February in Fargo is a study in gray and white. As the plane carrying Strom descended in the sunshine and warmth of Central Florida, “I was captivated by the palm trees, vibrant bougainvillea, and live oaks draped with Spanish moss. But most of all, I marveled at all the water,” she writes in “Wilderness from the Water,” her Wilder Hearts essay.

Strom, 57, specializes in agricultural history and rural studies. She writes books with titles such as Making Catfish Bait out of Government Boys: The Fight Against Ticks and the Transformation of the Yeoman South. The environment is her avocation and passion wherever she goes.

“I like to know the history of where I am,” she says. While teaching at North Dakota State University, she wrote a book about Fargo. She and her husband, Jim, explored the state by canoe.

“We used to do the Crow River in northern Minnesota,” she says. “One of the things that’s so different in Florida is the ecological diversity. Otters, alligators, a wide range of birds. You really don’t see that much in the North Woods.”

Strom was eager to investigate the myriad bodies of water that had enticed her from 30,000 feet. This is when she was reminded that she wasn’t in England anymore. She was born in Boston but had grown up in Cambridge and attended Oxford, where she was a coxswain on the rowing team.

“Most of England has been influenced by humans for millennia,” Strom says. “One of the things I miss so much about England is that it’s carved up by ancient byways and pedestrian footpaths protected by old medieval laws. It’s still very easy to get out into the countryside.”

In the U.S., she discovered, not so much. Strom found that most of those watery jewels she spied by air weren’t easily accessible. “Unlike the rivers of my English childhood, Florida rivers run through difficult terrain — marshes and thickets — so access by foot is difficult,” Strom writes. “Lakes, too, are difficult to reach, with shorelines either privately owned or swampy.”

There was only one way in: “Jim and I bought kayaks and opened ourselves to a whole new Florida, one dominated by nature where we could go all day without seeing other humans.”

Strom was fascinated to discover in the remote waterways the remnants of once-thriving communities Bulowville in Flagler County and Centralia in Hernando County, which were built around logging and sugar mills. These company towns, long since reclaimed by nature, were lively places populated by hundreds of families with access to stores and even movie theaters.

“The historian in me loves the cognitive dissonance,” Strom writes. “Floating past an alligator just off the dock where Bulowville stood, I imagine the stink of the processing sugar and the mounds of fermenting indigo leaves. Jim and I wave at an African American family from Sanford fishing in their favorite spot, where a century before hundreds of slaves had toiled loading cotton bales for transport out to the St. John’s. I think about the deep scars cut by cypress falling in the forest, the piercing shriek of a train whistle, the never-ending racket of the massive sawmill blades.”

Nature seems to have reclaimed much of the wilderness, but Strom notes that “the nature there now is not the nature that preceded it. They cut down all the cypress. The regrowth is different from what was there before. What you see now looks primeval but it’s not.”

Strom is cautiously cautious about the future of Florida’s environment.

“On the one hand, we see great strides being made, like the clean-up of Lake Apopka,” she says. “My husband and I saw a panther out at Merritt Island. At the same time, there are more and more people taking up more and more land. So, there are pluses and minuses.”

The biggest F-minus in Strom’s environmental gradebook goes to the cruise industry. “One of my passions is snorkeling,” she adds. “The cruise industry is ruining reefs around the world — Mexico, Belize, the Keys. Yes, I’m sorry that some people would lose their jobs. But if I could wish one industry away, it would be cruising.”

‘THE POSTER CHILD OF UNRESTRAINED GROWTH’

Bruce Stephenson might never have become a city planner if he hadn’t moved to the city that planning forgot. His family relocated from Kansas City to Merritt Island when he was 14.

“We lived on the Indian River lagoon and had a great life close to nature, but Merritt Island was one of the worst-planned places anywhere,” he says. “Courtney Parkway had two yellow lines but no park enhancing the way. Sidewalks were foreign objects and the Baptist church defined civic space. I didn’t know what city planning was — but when I went to college, I learned that’s what was missing in Merritt Island.”

His first inkling that the unincorporated Brevard County town lacked something came earlier, when his high school basketball team traveled to Winter Park for a game and he had his first look at a city that had essentially abided by the plan its founders drew up in the 1880s.

Stephenson saw streetside trees, public artwork, a downtown that wasn’t a shopping mall and comfortable places to gather that made a cohesive civic statement about what the city’s values were. He recalls thinking: “Oh, this is what planning is.”

He had also seen the ways in which poor planning made nature’s wrath worse. A severe drought in the winter of 1971 dried out mucky soil in the St. Johns River flood plain, turning it into a flammable peat-like substance.

“We started getting fires in February and they kept up for six weeks,” Stephenson says. “I had just seen Tora! Tora! Tora! Looking inland from Merritt Island, it was like the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. It was all exacerbated by poor planning that created environmental problems.”

In 1976, when Stephenson graduated from high school, no certified city planning program was offered anywhere in Florida. He earned a master’s degree in city and regional planning at Ohio State and was a city planner in St. Petersburg for three years. He wrote his first book, Visions of Eden, about urban planning in the city once known as “Heaven’s Waiting Room.”

Now a professor of environmental studies at Rollins, Stephenson serves as a consultant to Winter Park and to Portland, Oregon. He helped prepare the Winter Park Central Park Master Plan and led the ecological restoration of the Genius Preserve. A Stephenson class project led to construction of the Cady Way Trail. His new book, Portland’s Good Life: Hope and Sustainability in an American City, was just published.

Stephenson, who hasn’t owned a car since 2015, rented one to get to one of his favorite haunts, the Lake Wales Ridge State Forest near Frostproof in Polk County, the setting for his Wilder Heart essay, “The Natural Aesthetic of the Naked God.” It’s an existential meditation that extols “tapping into nature’s wild heart” as “the antidote to the cacophonic consumerism that prices our lives and steals the soul.”

The essay demonstrates that Stephenson can thunder like an Old Testament prophet: “The poster child of unrestrained growth, Florida is in peril. Its unique system of land and water has been engineered into the backdrop of suburbia. Awash in toxic algae, red tide, and saltwater intrusion, this specter is matched by the state’s mechanized death. In road-rage-riveted metropolitan Orlando, a driving fatality occurs every 44 hours, pedestrians are impaled weekly, and bicyclists die at an equally foreboding rate.”

Yet Orlando is not doomed, Stephenson says, thanks in part to the city’s Greenworks Plan, a variety of initiatives adopted in 2018 to make the city more resilient to the impact of climate change, and to the State Legislature’s appropriation of funds for natural lands acquisition.

Stephenson, 65, has been at Rollins since 1988. How close to midnight was it on the environmental doomsday clock for Florida then? And now? “I would say it was like 10:30 then,” he says. “It’s 11 o’clock now — but the clock is not moving quite as fast.”

Does anybody really know what time it is? Not really. Does anybody really care? Read The Wilder Heart of Florida and you’ll meet plenty of people who do.

Seduction In Key West

Susan Lilley

Back behind the white-lattice cafes with their fragrant garlic

and Key Lime daiquiris, vines that go back centuries

grow wild around the dumpster. Long before

the gay tea dances and Hemingway and smugglers

and rum runners, this string of islands witnessed steel-hearted

pirates and Spaniards seeking gold, Seminoles, and the murderous

Calusas, who executed enemies by tying them

to the green manchineel apple tree and walking

away to let the tree’s poison sap eat slowly

through the clothing to the skin,

to the bones underneath.

It’s Saturday, and the cruise ship opens its maw

like a great white and expels the tourists onto dizzy

Duval Street. The town is ready for them with conch

fritters, salty edged tequila, clattering shell necklaces,

and a replica of an eye-gouging machine

at the Pirate Torture Museum. Six times a day the guides

at Hemingway’s revive old scandals, still tart and delicious

after fifty years. Ghosts must love the old

gossip here in the glimmery aquamarine daylight.

Vacation girls show off new henna tattoos

on ankles and arms and down low on sunburned backs.

No Calusas remain. But the poison apple still grows

on the smallest, wildest keys, flowering and sending forth

seductive green fruit, which most creatures wisely ignore.

Even a tiny Key deer knows better than to stand

under this tree in the rain. But imagine a tourist

who seeks the unspoiled, who might take a canoe

without guide or map, negotiate the floating mangroves

that encircle each island like a guardian net of leaves,

and filled with wonder, walk his camera to the inevitable

clearing where, in a dim circle of a forgotten

world, this lonely tree waits

and spreads its bright green danger.

From The Wilder Heart of Florida: More Writers Inspired by Florida Nature, edited by Jack E. Davis and Leslie K. Poole.

Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2021. Reprinted with permission.