Billy Collins once compared what he does for a living to taking people out for a drive and then dropping them off in a cornfield, a little dazed but none the worse for wear.

Good thing for him that it’s just a metaphor, given how hard cornfields are to come by in Winter Park, where the 79-year-old native New Yorker and former two-term U.S. poet laureate has been living since 2007.

Good thing for us, too, now that it’s time for another joyride.

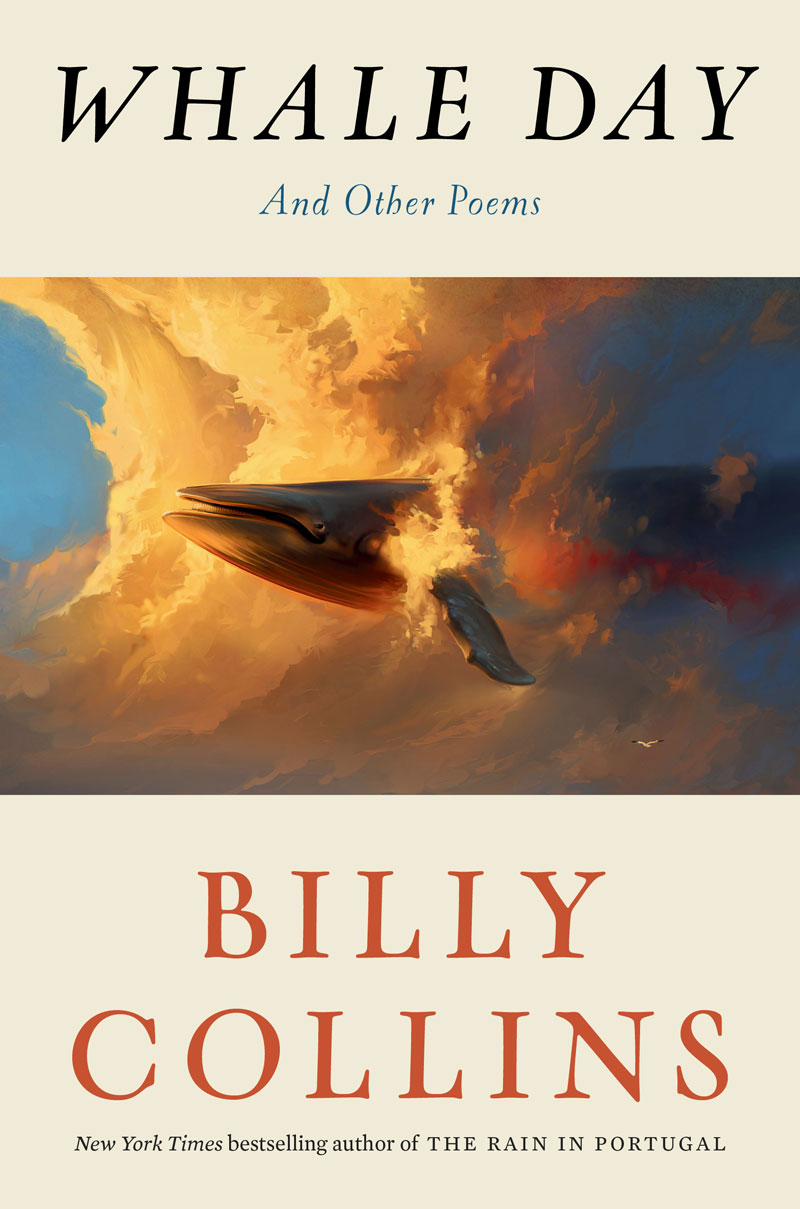

Whale Day: And Other Poems (Random House, 2020), published in September, is Collins’ 13th volume of verse — and his sixth since moving to the home near downtown where he lives with his wife, Suzannah. The previous book, The Rain in Portugal, was a New York Times bestseller.

The new collection demonstrates that Collins, who has been described as the most popular poet in the country, remains a shrewd craftsman and puckish storyteller.

As is his custom, Collins named his latest collection using the title of one of its poems, which in this case revolves around his whimsical suggestion that we ought to create a holiday to honor whales in recognition of their epic circumnavigating:

So is it too much to ask that one day a year

be set aside for keeping in mind

while we step onto a bus, consume a ham sandwich,

or stoop to pick up a coin from a sidewalk

the multitude of these mammoth creatures

coasting between the continents,

some for the fun of it, others purposeful in their journeys.

Collins is a dedicated and imaginative ferryman, ever ready to arrange transport for himself and his readers through the lukewarm haze of day-to-day life toward humble or hidden wonders more often near than far.

Here he is, in “Walking My Seventy-Five-Year-Old Dog,” traversing his usual route with an elderly canine companion:

She’s painfully slow,

so I often have to stop and wait

while she examines some roadside weeds

as if she were reading the biography of a famous dog.

Here he is in the grocery store produce aisle with a poem dubbed “Banana School,” which revolves around his recent discovery — no telling where he heard it — that humans are the only primates who peel the eponymous fruit from the curved stalk at the top.

The day I learned that monkeys

as well as chimps, baboons, and gorillas

all peel their bananas from the other end

and use the end we peel from as a handle,

I immediately made the switch.

Go ahead. We’ll wait. Try it. It will make you wonder where else along the line we as a species have gone terribly, terribly wrong. Then take the time to consider whether you favor sleeping on your right side or your left.

This is not generally a topic that comes up in casual conversation. But that’s why Billy Collins is the poet laureate and we are not — or as he would say: “Poets have to keep track of these things.”

Hence: In “Sleeping on My Side,” one of several poems in which Collins has his poetic persona speak as if addressing a close friend, an acquaintance, a perfect stranger — or, in this case, his wife — he muses:

At home, it’s the east I ignore,

with its theaters and silverware,

as I face the adventurous west.

But when I’m out on the road

in some hotel’s room 213 or 402

I could be pointed anywhere.

yet I barely care as long as you

are there facing the other way

so we are defended in all degrees

and my left ear is pressing down

as if listening for hoofbeats on the ground.

This poem is not the quirky little confection you might initially take it to be. It’s a love poem that emphasizes how lucky some of us are to be blessed with the company of someone who always has our back. In its simplicity, it says more about relationships — and says so more powerfully — than the most florid epics you’ll ever plow through.

Collins travels widely — at least he did before the virus descended — and there are dispatches from abroad in Whale Day that showcase his inventive descriptiveness.

Here are four stanzas I especially like, from “Lakeside Cottage: Ontario,” in which Collins shares both the sight of Canada geese and the emotions engendered by watching them in flight:

and they flew from right to left

like a text written in Hebrew

almost touching the slightly ruffled water

as they passed by the dock at the end of the lawn.

You know, the dock with the little flight of stairs

that disappears into the lake, which made it easier

for your parents to go for a swim

in the cold water before they both died

only months apart, as if Jack followed Mary’s lead.

Otherwise, they might be sitting here now

in the two chairs by the picture window,

maybe holding cups of morning coffee,

as all the geese sailed by, heading who knows where

so close to the water, each holding its position,

the leader pointing the way with its neck

extended, as if he were pulling the others along.

Not surprisingly, given Collins’ stage of life, there are several poems about mortality in Whale Day. When I mention this, he tells me that age has less to do with their presence than I might have thought. Poetry, he says, regardless of the age of the poets and the era in which they write, is eternally dedicated to boiling life down to the basics.

That makes death one of two mainstays bound to be in the spotlight as long as there are poets, pens and paper. “Love and death are the magnetic poles of poetry,” Collins notes. “And there’s that quote from Kafka: ‘The meaning of life is that it ends.’”

Naturally, any guest appearance mortality makes in a Billy Collins production is going to happen on the poet’s own terms. In “Cremation,” a poem about deciding whether or where to have one’s ashes scattered, he brings one of his favorite comedians on stage to weigh in:

Now, I’m not sure how you heard it,

but in my version, Bob Hope’s wife

asked her husband on his deathbed

whether he wanted to be buried or cremated.

“Surprise me,” replied the comic before expiring.

Other poems about mortality, however, don’t have such overt punchlines. In “Life Expectancy,” Collins reflects on the fact that he can no longer be assured of outliving the animals he observes, while in “Me First” he suggests that the older partner in a relationship, meaning himself, ought to be the first to die.

Similar themes are explored in the poignant “On the Deaths of Friends” and the surreal “My Funeral,” in which Collins imagines a traditional memorial service followed by a celebration with musical accompaniment provided by an assortment of wild animals.

Collins, obviously, is far too wry to get morose, even about final farewells. And he’s too much of a New Yorker to get overly sentimental — although some of these poems will surely evoke some combination of goosebumps, misty eyes and ragged sighs.

Emotional heartstrings may also be tugged when Collins waxes nostalgic in “My Father’s Office, John Street, New York City, 1953,” which turns remembrances of childhood visits to a lower Manhattan high-rise into an elegy for the vintage trappings of insurance-sales outposts such as fountain pens, rotary phones, paperweights and stacks of documents.

Collins’ poems often start with such seemingly random observations but end with a gut punch — a trademark of his work. After lamenting the now-obsolete ephemera of this unremarkable Eisenhower-era business office, he concludes by noting, “And gone the men themselves and gone my father / gone my father as well.”

Despite the pandemic’s restrictions, Collins is as industrious as ever. He writes nearly every day; as he says in an introductory poem in Whale Day, “…the function of poetry is to remind me / that there is much more to life / than what I am usually doing / when I am not reading or writing poetry.”

“The Function of Poetry” reminded me of a famous statement once made by Robert Frost: “My goal in living is to unite my avocation and my vocation, as two eyes make one in sight.”

Collins also makes multiple online appearances at poetry seminars and readings. In addition, he conducts The Poetry Broadcast, his own late-afternoon production five days a week that is accessible through his Facebook page. It’s a format ideally suited to his witty and casual conversational style.

The sessions are introduced with vintage jazz classics from his extensive collection. They’re followed by 30-minute readings and lively discussions of his own works and the poems of other classical and contemporary authors.

According to a recent profile of Collins in The Wall Street Journal, nearly 50,000 fans from around the world have tuned into the broadcast. Real-time comments have been noted from across the U.S. as well as from Australia, Bangladesh, Belgium, Copenhagen, Italy and Nigeria.

In one of his Whale Day poems, Collins describes Winter Park as “the quiet cardigan harbor of my life.” With all due respect to the esteemed poet laureate, I’m not sure “quiet” is the word I’d use.