Editor’s Note: Rita Bornstein, president of Rollins College from 1990 to 2004, is known is known today as a prodigious fundraiser and the president who elevated the institution into the upper tier of liberal arts colleges. Although her professional accomplishments are well known, Bornstein has written little about her personal life and the forces that shaped her into one of the most significant leaders in the college’s history and, after retirement, into a civic dynamo and community icon. Now, she has provided this fascinating look at her background and career, which we are pleased to present in Winter Park Magazine.

My inauguration as president of Rollins College, in April 1991, was rich with pomp, history, symbolism and ritual. Such events are important because they build a sense of continuity, belonging and pride at a time of uncertainly.

I was fortunate to have on the stage with me three living past presidents — Hugh F. McKean, Jack Critchfield and Thaddeus Seymour — who together placed the college’s medallion around my neck. In addition, Tad Foote, president of the University of Miami — my longtime mentor and previous employer — had made the trip to be with me.

When the celebration of the college’s history and the investiture of the new president concluded, my mother asked me privately, “How did such a shy little girl grow up to be a college president?”

I was astonished myself. I didn’t come to the Rollins presidency with the preferred bona fides. I hadn’t been an academic vice president, dean or tenured faculty member. I had been the vice president for development at the University of Miami, and came with a complicated series of life and career experiences.

As a nontraditional president — Jewish, a woman and a fundraiser — I faced special challenges in gaining respect and legitimacy from the faculty, the trustees and the community. Without such acceptance, my efforts would be fruitless. Interestingly, many of the presidents who preceded me also had nontraditional backgrounds, including a minister, a newspaperman, an artist, a corporate executive and a student affairs officer.

Fourteen years later, when I retired, I was satisfied that, building on the work of our predecessors and through the efforts of colleagues and supporters, Rollins was far stronger in quality, prestige and financial health. I had faced some difficult moments — but overall, I loved the job and achieved my goals.

This brief history is an attempt to disentangle the major threads of my life and identify the experiences, values and qualities that contributed to any success I had. My mother and I were asking the same question: How did I become the person I was now?

MAKING MY WAY

My parents were from immigrant families. My mother, at 10 years of age, fled with her parents from the oppressive and anti-Semitic regime in Russia. The family spent three years in Harbin, China, a haven for disaffected Russians.

My maternal grandfather had been the only Jewish Singer sewing machine salesman in Moscow and a tradesman in China. But when his family arrived at their long-awaited home in New York, he had to depend on relatives for employment.

One of the most enjoyable things that my grandmother, mother and I did was to sit together in the kitchen, me often perched on the table, and sing Russian folk songs. I still remember several of those songs and, if persuaded, can sing them to this day.

My grandparents spoke only Russian and Yiddish but my mother, determined to fit in, learned to speak perfect, unaccented English. This was quite an accomplishment at a time when immigrants didn’t have easy access to special language programs.

My mother completed high school in New York, but girls at that time weren’t encouraged to prepare for a profession. She was resentful and unhappy about this all her life.

My father’s parents, immigrants from Austria, owned a grocery store on the east side of Manhattan within walking distance of their apartment. They took my father out of high school to work in the store and help earn the money needed to put his three younger brothers through college.

This he did without complaint. But after he was married, his work hours kept him away from our family most of the time. I remember him leaving before sunrise and usually not returning until after dark. Years later, my father earned his GED and went on to secure a college degree. He never boasted about these accomplishments.

Despite the limits placed on her by her parents and society, my mother had extraordinary drive and ambition. She read widely, wrote poetry, watched only educational television and aspired to high culture. She always believed that the more expensive something was, the better its quality must be.

I learned from cousins that my mother was greatly admired in the family for her style and her sophisticated clothes. My brother and I were always dressed well for school. And, not surprisingly, our pediatrician was the famous Dr. Benjamin Spock.

With both parents stymied in their potential and ambition, the atmosphere at home was bleak and sad. My father was a model of sacrifice, stoicism and hard work. Although he was well-liked and generous, he was not expressive or affectionate. My mother, on the other hand, was hungry for affection. They were not well matched.

On reflection, our home life seems very fragile. I’m not certain what fragility meant to me in that context, but I was often on guard. Once, in the early evening, my mother was resting in her bedroom with the lights off due to one of her headaches. No one else was home, and although I was doing homework, I kept an eye on the bedroom.

When she got up and went to the window, I ran in to help because I was certain that she intended to throw herself out. She assured me that she wasn’t about to commit suicide but simply needed more air. I felt silly and she laughed it off. We never again spoke of it.

We talked, sang songs, made up stories and played school. I was the stereotypical bossy teacher. These activities made us both feel better and provided distraction. My capacity for empathy evolved as I saw the challenges faced by each of the people I loved.

Once, when I was about 12 and Arnie about 8, he came upstairs from the street crying, with blood streaming down his face. He told me that a boy had thrown a broken bottle at him. Mother wasn’t home, so I took him into the bathroom and cleaned him up. Then I walked him the 10 blocks or so to the doctor’s office, where he got two stitches in his cheek.

I felt like a superhero — but that glow was extinguished when we got home. Mother was there, and Arnie covered his face, afraid of what she might say. Fortunately, she hadn’t yet gone into the bathroom, which was scattered with bloody towels.

I was shocked a few years ago when Arnie gave me a box of letters that I had written him over the years. My desire to be a teacher was evident. In every letter, whether it went to his university or later to Vietnam, I offered advice — that he had not asked for — about how to live, what to read and what to think.

To her credit, my mother found the funds to ensure that I broadened my perspective by studying piano and dance. As with everything, she sought the best to provide my training.

As a nontraditional president — Jewish, a woman

and a fundraiser — I faced special challenges in

gaining respect and legitimacy from the faculty,

trustees and community. Without such

acceptance, my efforts would be fruitless.

I had the privilege of studying modern dance with legends Martha Graham and Katherine Dunham. I remember the excitement of doing floor exercises while sitting across from Ms. Graham as she repeatedly instructed us to start the movement from the pelvis: “All emotion begins in the pelvis!”

My mother also found Buck’s Rock Camp, where we would spend our summers. This camp had a profound effect on my emotional and intellectual development.

Campers were expected to make their own decisions about daily activities, and we worked in the gardens to harvest vegetables and fruits for meals. We also washed and fed farm animals — although we didn’t eat them — and campers were encouraged to express themselves through arts activities.

We made bowls out of blocks of wood and sang folk songs. I choreographed and danced in a challenging play — T.S. Eliot’s The Hollow Men — and danced to the words of “Poets to Come” from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Most important, I interacted with young people and adults who were more diverse, creative and progressive than my family and friends.

My mother’s parents were modestly involved in Jewish life, but my parents weren’t involved at all. However, in her usual way, my mother identified two extraordinary nontraditional institutions to offer us religious and intellectual education: One was the socially conscious Stephen Wise Free Synagogue and the other was the New York Society of Ethical Culture, which promoted secular humanism.

I was about 14 years old when one of my father’s brothers helped him start a fluorescent lighting business. The additional income generated by the store allowed us to move from Manhattan to Queens and attend better schools — a move my mother thought would be good for us. It was not.

ACTS OF REBELLION

As a student in the city, I had been promoted one grade ahead for my age and so was out of sync with my new classmates. I found them cliquish and snobbish, and I just didn’t fit in.

My act of rebellion was to befriend another disaffected student, with whom I made weekly visits to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. There we made friends with other disaffected souls who enjoyed singing folk songs and strumming guitars and banjos.

The next few years were tumultuous for me. The University of Chicago accepted me as a student, but I had no idea of the extraordinary reputation and prestige of the institution. I didn’t know anyone at the school or in the city, and my boyfriend had just dumped me.

I was unhappy, and after just three months left school and returned to New York. Like many teenagers, I didn’t consider the consequences of this impulsive decision. Years passed before I went back to college and came to realize what I had given up in Chicago.

When I returned to New York, my mother agreed to let me stay with her. She had her own troubles, however, having finally left her difficult marriage. After a short time, I realized that neither she nor I was comfortable with this arrangement.

Acting again on impulse, I packed a suitcase, took my guitar and boarded a bus for Los Angeles. I knew no one there but had the phone number of a friend of a friend. And so, a new chapter in my life began as the result of a trip that was really brave or really stupid — or perhaps some of each.

My rebellious high school years, my abandonment of a unique opportunity in Chicago and my spontaneous journey to the West Coast seem to belie my characterization of myself as being shy and lacking in confidence.

But the willingness to take risks helped me gain confidence as I matured — and I may have saved myself by disconnecting from my dysfunctional family.

In Los Angeles, where once again I was alone in an unknown city, I worked at a series of low-level jobs that didn’t challenge my interests or abilities: waitress, receptionist, dental assistant and on an automobile assembly line.

I wrote a few lines expressing the way I felt about the factory: “A streak of gold for a moment, Radiant glance of the sun. Here where it is dirty and cold and mechanized. Beauty in dark places.”

I also found my way to one of the premier dance studios in the country: the Lester Horton Dance Theater in Los Angeles, one of the first permanent theaters dedicated to modern dance in the U.S.

Horton, who died in 1953 and whose former students included Alvin Ailey, had developed his own style of modern dance; I found it comfortable since it was similar to Graham’s approach to movement. On occasion, we had the opportunity to choreograph and perform before audiences.

Amazingly, I still have a letter that I received more than 40 years ago following one of those performances. It’s from a woman named Donna Cilurzo, whom I don’t remember. It reads:

“You were just magnificent and, especially in The Gypsy Nun, which in my mind was the high point of the evening. Not only was your work technically beautiful, but even more important, your inner fire and depth of characterization really came across.”

Despite accolades such as this, I knew I was merely a good dancer but not a great one. However, many years of dancing and choreographing had helped me become disciplined, strong and confident.

Acting again on impulse, I packed a suitcase, took my

guitar and boarded a bus for Los Angeles. I knew no one

there but had the phone number of a friend of a friend.

And so, a new chapter in my life began as the result

of a trip that was really brave or really stupid —

or perhaps some of each.

I found myself married, far too young, and became a mother when I was just 20. I think it’s fair to say that Rachel, my daughter from that marriage, and I grew up together — and it wasn’t always easy.

After several years in Los Angeles, I realized that this wasn’t the life I wanted. I was frustrated in ways that I couldn’t have articulated at the time. I realize now that I was yearning for more. I wanted more education. I wanted to make an impact. I wanted to find my voice.

I divorced and moved with Rachel to Miami, where my mother now lived. Although my relationship with her was tense, she served as an anchor of sorts. I continued to work in a series of low-level jobs as Rachel and I settled in.

I was determined to navigate back to school, although, as a single parent, the path wasn’t an easy one. Eventually I remarried, and soon after my son, Mark, was born. I started taking college classes at Florida Atlantic University. I would continue my education for 15 years — until 1975, when I earned a Ph.D. in educational leadership from the University of Miami.

While my children grew up somewhat resentful of my commitment to school and later to work, they were proud of me. I must admit that it was a real challenge to find a balance between my school and home life. In 2016, I was gratified when Rachel wrote in a letter to me that “you had more determination and grit than anyone.”

I was a highly motivated student, excited by my classes. I was elected president of an organization called Women’s Organization for the March on Education Now! (WOMEN!), which was founded to press college authorities to be more responsive to the needs of older women returning to school. This was my first foray into gender politics.

I juggled the demands of school with the challenges of raising children, and often felt guilty about the choices I made. However, I’ve always been grateful that I was able to develop my capacity for intellectual growth and professional success.

Having loved language and literature all my life, I majored in English literature and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from FAU. My master’s thesis was titled Revolutionary Black Poetry 1960-1970 and my doctoral dissertation was about an innovative attempt to radically improve public education.

It was a topic in which I would soon have real-world experience.

REFORMING EDUCATION

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, many books were published extremely critical of the “factory model” of public schools that engendered “obedience, passivity, and alienation” among students. As a result of this widespread critique, many educators began rethinking education with a goal of encouraging creativity, flexibility and responsibility.

Dr. Kenneth Jenkins was the principal of North Miami Beach Senior High School, a brand-new school set to open in 1971. He invited me to join a new committee charged with the design of an innovative model for secondary school education.

I was thrilled, but apprehensive. I was still working on my master’s degree, and my only classroom experience was as a student teacher under the supervision of an experienced professional. Still, I couldn’t say no.

Later, Dr. Jenkins invited me to serve as team leader of one of four planned “little schools” within the larger school, which had 3,600 students. I would be chief of “Little School C,” with 950 students, 25 interdisciplinary teachers, the football coach and three counselors.

Our goal was to upend the traditional education system by enhancing personalization and encouraging self-directed learning with no traditional letter grades. The school was dubbed “experimental” in the media.

Anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson points out that many women, when they secure positions for which they don’t feel adequately prepared, suffer from “impostor syndrome” — fear of being exposed as a fraud. That was me.

Although the project was widely heralded when it began, problems emerged within a few months. Most students adapted to the new atmosphere and learned to accept increased responsibility for their own education.

However, a substantial number abused their new-found freedom by spending their time at a nearby shopping center and the beaches, or by sitting around the school grounds playing guitars.

To complicate the situation further, the planning committee had been so preoccupied trying to fulfill our charge that we didn’t prepare for — or even discuss — the impact of Black students being bused to the school for the first time.

Our young, liberal teachers wanted Black students to feel welcome. As a result, they were lax regarding academics. But low expectations usually lead to poor performance. That’s what’s meant by the phrase “the bigotry of low expectations.” It was a painful lesson to learn.

By the end of the first year, the flexible schedule had been replaced by traditional 50-minute periods, and letter grades were instituted. By June 1974, Dr. Jenkins had resigned under pressure, the original staff had dispersed and most of the innovations had been curtailed or eliminated.

Most similar change initiatives around the country also failed as a “back to basics” mindset emerged in public education. I was named chair of Little School C’s English department and supervised a return to traditional systemwide rules and expectations.

This experience was instrumental in my leaving public schools. When the innovative program was dismantled without input from, or discussion with, the new program’s designers and participants, I lost confidence in the system’s ability and willingness to change.

I had been working on a Ph.D. in educational leadership at the University of Miami, and in 1975 analyzed the colossal failure of our program in a 450-page dissertation titled An Historical Analysis of the Dynamics of Innovation in an Urban High School.

I examined the strengths and weaknesses of our approach and the obstacles to, and tools for, promoting and leading change. I investigated the tendency of change agents to expect their innovative new designs to be applied uniformly.

One of the recommendations I made was summed up this way: “Missionary zeal must give way to a realistic appraisal of the differing needs and attitudes of students, teachers and parents, and these must be accommodated. Failure to provide options may foredoom an innovative project.”

Writing that dissertation helped me overcome my disappointment and grief, but the potential of innovation and change continued to influence my career choices.

Reviewing my job history, I realize how much support I received from a series of mentors who, like Dr. Jenkins, took an interest in my career, opened doors for me and encouraged me to accept responsibilities for which I felt unprepared. They saw leadership qualities in me that I did not recognize myself.

EQUALITY AND FUNDRAISING

My next professional experience, through the University of Miami, was no less daunting. For four years, 1975 to 1979, I was field director for the School Desegregation Consulting Center, funded by the U.S. Office of Education, with responsibility for Florida and Georgia.

This was important work, but I had been particularly interested in Title IX, the 1972 federal law that prohibited schools from discriminating on the basis of sex. In 1975, I had submitted a proposal through the university to get federal funding for a regional assistance center to aid schools in Title IX implementation. My proposal was denied, and I was devastated.

I later wrote a much stronger proposal, which was funded, and in 1979 became director of the Southeast Sex Desegregation Assistance Center. I also wrote a proposal for a second federal grant that would enable me to designate a specific school and position it as a model of sex equity. This project, which involved a grade school in Broward County, was also funded.

As part of my work as director, I traveled frequently to schools and colleges throughout my region. Wherever I went, I explained the new federally mandated regulations regarding Title IX.

Audiences were generally hostile to my message. Facing groups of angry parents, administrators and coaches upset me at first — but I learned to listen and to be sensitive to the discomfort being expressed. All leaders must learn to do this.

In the years since, Title IX has made an incalculable positive change in schools and society. Sports programs have been transformed, and many girls and women have been attracted into professions formerly considered off-limits.

It’s worth noting that the first school transformation with which I was involved — North Miami Beach Senior High School — collapsed under the weight of a large traditional system. In contrast, the effort to equalize opportunities for women and men was nationwide and had the force of law behind it.

My next job evolved naturally from my work as an advocate for Title IX and champion of opportunities for women. I heard that the male-dominated field of development (or fundraising or advancement) was just opening to women, so I requested a meeting with the vice president for development at the University of Miami.

Within a few weeks, he offered me the position of director of the university’s Office of Corporate and Foundation Relations, which meant a cut in pay and status.

Why did I consider such a drastic move? For years, I had been working on federally funded grants and contracts at the university. However, the national political scene was changing, and I held out little hope that such federal programs would continue.

I regularly taught courses in education, but knew that the university had a firm rule about not hiring graduates into tenure-track professorships. Having severed my ties with the public-school system, my options were limited. It was only later that I understood the power of fundraising to improve an institution’s profile and status.

The job I took was at the bottom of the development career ladder. However, a year later, President Tad Foote, having worked with me on several important fundraising projects, saw to it that I was promoted to associate vice president for development.

President Foote had persuaded the board of trustees to conduct an ambitious “Campaign for Miami” to raise $400 million. That, and a concurrent $400 million campaign at Columbia University, were at that time the largest fundraising efforts that had ever been conducted in American higher education.

With presidential leadership and vision — and the hard work of consultants, staff and volunteers — we created an army of advocates for the university. At a black-tie event celebrating the successful conclusion of the campaign, it was announced that we had raised a grand total of $517.5 million over a seven-year period. We were all ecstatic.

Several years into the campaign, the president of Brandeis University offered me the position of vice president. I wasn’t trying to improve my status or salary at UM when I told President Foote about this opportunity. So I was surprised when he quickly consulted with the trustees, reorganized the administration and offered me the vice presidency.

As vice president, I was fortunate to sit in on trustee meetings and became conversant about higher education issues and politics. I came into the field of development as a novice, and over the years became interested in the traditions of fundraising in America.

The Campaign for Miami represented an effort to strengthen the image and resource base of an institution known as a “cardboard college” because of its slapdash architecture and construction. It was another early Florida institution of higher education with a weak reputation and scant resources.

The funds generated by the campaign, along with strong presidential leadership, helped thrust the university into national prominence. (Others might attribute this to the success of the football program.)

FROM A HURRICANE TO A TAR

In 1990, banker Charlie Rice, a Rollins trustee who served on the Presidential Search Committee, invited me to apply for the top job. He knew me well, because he was also a trustee of the University of Miami. Were it not for him, I wouldn’t have surfaced as a likely candidate. In fact, I wouldn’t even have applied. This is another example of how important mentors can be.

Once my name was in the mix, Charlie advised me that my candidacy was in my own hands. I took that seriously. Developer Allan Keen, a Rollins graduate and board member, chaired the search committee. I was appreciative of the fact that he kept in regular contact with me during the long and arduous process.

As I wrote in a journal, which I continued to keep throughout my presidency, the search involved “activities [that] were strenuous and challenging, called on everything I am and know, have read, have felt, have thought, and I was at my very best and better than I could have imagined….”

I did my research before I met with the committee and various constituents. I knew that since its founding by the Congregational Church in 1885, Rollins had been challenged by extremes of weather and vicissitudes of the economy. It had been in danger of closing its doors several times during its history.

I had also become aware that Rollins was known around the state as “Jolly Rolly Colly,” noted for “fun in the sun.” This distressed me. I told the trustees and the faculty that I would need them to work alongside me to build a college known for academic excellence. All the while, my confidence grew that I could make a difference.

I also began to feel a real affinity for the Rollins faculty. They were devoted to their students and talked about teaching as an art and a calling. The faculty’s commitment to innovation and internationalism was encouraging to me; both were important legacies of the legendary Hamilton Holt, the college’s eighth president.

After three visits, the trustees voted to offer me the position, and I returned to Miami with great excitement and anticipation. Imagine my surprise when, in reviewing the college’s charter, I found that the president “shall be a practicing Evangelical Christian.”

In a panic, I called the college’s attorney and told him that I couldn’t take the position. He advised me to disregard that language because it was obsolete and not binding. I was reassured — but asked him to put it in writing, which he did.

As I prepared for the next phase of my life and work, knowing that much would be expected of me, I was buoyed by a comment made by Ernest Boyer, esteemed president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Boyer said that I had not only administrative skill, but also the “quality of human spirit” that would make me a “great” leader. My brother Arnold was also pleased but found a less classy way to support my new position. He came to visit wearing a T-shirt that read: “My sister is President of Rollins College.” What fun!

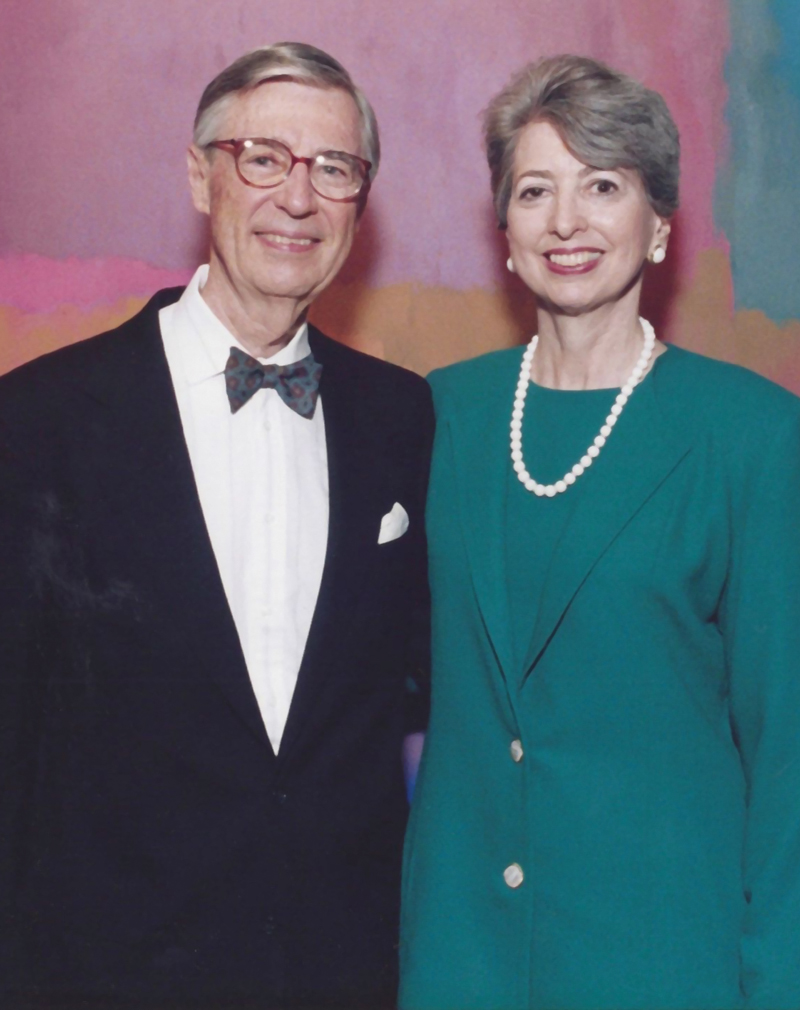

My predecessor at Rollins was Thaddeus Seymour, who had retired after 12 years at Rollins and a previous presidency at Wabash College in Indiana. He was well regarded by everyone and welcomed me and my husband, Harland G. Bloland, professor of higher education at the University of Miami, warmly.

As soon as I was elected, Thad put up a sign saying, “Welcome Rita” and rang the bell at Knowles Memorial Chapel to announce my appointment. Soon after we arrived, he and his wife, Polly, hosted a party for us to meet members of the community. He insisted that I sit beside him and be introduced at commencement.

Thad was a model for a departing president’s responsibility to ensure a smooth transition. His behavior elicited a reciprocal feeling in me.

I prepared for my formal inauguration as 13th president of the college by writing an address for the occasion that presented my vision for Rollins and defined my presidency.

My goal was to have Rollins recognized as one of America’s best internationally focused and community-involved colleges, with acclaimed liberal arts and business programs. To achieve this status, we would need to significantly improve the college’s quality, reputation and resources.

I also wanted to recognize and build on the unique and innovative history of the college, which included Holt’s Conference Plan, designed to engage students in active discourse rather than the passive acquisition of knowledge delivered by lecture.

That same storied history included a 1931 conference, Curriculum for the College of Liberal Arts, chaired by educational philosopher John Dewey. Attendees explored the possibilities of applying classroom learning to social problems and internationalization of the curriculum, faculty and student body.

In my address, delivered on April 13, 1991, before an audience of about 1,500 people, I proposed an underlying principle (or motto) that would guide us throughout my term: “Excellence, Innovation, and Community.”

Now I was ready to answer my mother’s question. That shy child we both remembered was gradually transformed into a college president through the experiences of her life and the encouragement and support of many people throughout the years.

SKEPTICS ANDS CHALLENGES

I received a great deal of enthusiastic support as president — although I wasn’t immune to the many insults and negative comments that began as soon as I started on the job.

I was shocked when I learned that a prominent alumnus had cautioned publicly, “This college is not ready for a Jewish woman president.” Another alumnus, whose home I visited in North Florida, told me that he doubted whether I would ever be accepted in Winter Park.

There was even an anonymous letter to each trustee asserting that my financial vice president and I were destroying the college. I had the pleasure of watching attorney Harold Ward, one of the most prominent trustees, tear the letter to pieces in front of me.

I was pleased to learn that I would work with community leader Betty Duda, the first woman to chair the trustees. She was very welcoming, but asked if I thought that locals would be concerned that two women now oversaw the college. It was a concern that we dismissed.

Overall, though, I was pleased to find that friends of the college shared my goals of building an institution of excellence and securing the resources necessary to assure current and future students a world-class education.

In the meantime, I became aware of two national trends that would unquestionably impede our ambitious plans. I reviewed these trends in my 2003 book, Legitimacy in the Academic Presidency: From Entrance to Exit.

The book, by the way, received enthusiastic reviews by several well-known presidents and scholars, and has become required reading in a number of higher education graduate programs.

Frank Rhodes, former president of Cornell University, wrote: “Bornstein’s highly textured book deserves to be widely read by those concerned with the leadership and well-being of American higher education.”

The first trend I discussed was a serious financial recession in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which prompted predictions of the most challenging era for higher education since the Great Depression.

The so-called “Age of Scarcity” did indeed see escalating costs, a steep decline in college-age young people, cutbacks in federal and state support, and intense competition for students and philanthropy. The future looked especially dire for underresourced institutions.

The other trend was the vigorous and unrelenting attacks on higher education by academics, journalists and legislators on the basis of some well-publicized abuses and misconduct — including rule violations in big-time athletics, misuse of government-sponsored university research dollars and high levels of student loan defaults.

Fortunately, by the mid-1990s economic conditions had improved dramatically, creating an extraordinary opportunity for growth and rebuilding. Institutions like Rollins that had focused on strategic and campaign planning were ready to move ahead.

I noted in my journal that “the job takes a huge amount of energy, motivation, and commitment. …it is just plain hard work and I can see why a president would wear out eventually…No one who hasn’t been in it can truly appreciate the challenge. No vice president is close enough to understand it, or any trustee, or any consultant, or even a spouse.”

The presidency is characterized by continuing demands of all sorts, including unexpected events and occurrences that require quick but judicious decisions. All hell can break loose in a totally unexpected way in a totally unexpected moment.

A good example of the array of surprises that I experienced was a letter that arrived from Okinawa, Japan, requesting that the college return a statue given to President Holt by a graduate following World War II. This request came at a time when there were many disputes between nations, universities and museums over ownership of art and artifacts.

Despite considerable pressure from the Orlando Sentinel and the New York Times, the college’s trustees declined to return the statue. However, I continued to explore the issue and discuss it with student, faculty, community and higher education leaders.

It was a graduate of Rollins, who was then serving as an ambassador to Japan, who persuaded me that returning the statue was the right thing to do and would enhance relations between our countries.

We received an almost exact replica in return. In addition, Harland and I were invited to Japan, where we established a relationship with the school that housed the artifact. As a result, Rollins faculty continue to teach and learn in Japan. I published an article on the experience in The Chronicle of Higher Education — and Rollins set an example of ethical decision-making.

Not everything about the presidency was so serious. On a lighter note, there never came a time when the way I dressed, wore my hair and selected jewelry wasn’t a topic of discussion. Indeed, fascination with the appearance and attire of female executives continues today.

After I retired, a woman from the community commented that I was very “starchy” during my presidency. My friend, former Orange County Mayor Linda Chapin, says that I was always “the president” and not the relaxed, funny person that I turned out to be after I stepped down.

Some faculty members felt that I was too “corporate” for Rollins, where women professors, according to my husband, were 1960s manqué in their “dirndl skirts and sandals.”

That some saw me as corporate was the result of my being a captive of the then-popular “dress for success” look for women — a man-tailored blue (white stripe optional) business suit with a white blouse and a blue or red tie at the neck.

While I was experienced and outwardly confident, I didn’t entirely avoid imposter syndrome. Could I really do the job? Could an infusion of resources and clarity of vision assure the college’s growth in prestige and influence? Could a president successfully install a commitment to excellence throughout an institution?

I felt empowered when Joanne Rogers began calling me “Prexy.” Joanne and her husband, Fred, were both Rollins graduates and remained close to the college. Fred became internationally famous as Mister Rogers and creator of the PBS children’s program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

I enjoyed being called “Prexy” because that was the affectionate title students had given to Hamilton Holt. Being compared with Holt was a great honor, since he brought national attention to the college as an educational innovator and champion of world peace.

It was a treat to go out to dinner with Fred and Joanne during their annual sojourn in Florida. Fred tried to be inconspicuous, but was such an icon that everybody recognized him and approached him as they would have a close friend. He was always genial about the attention.

TAKING COMMAND

It’s hard for presidents to get honest feedback about their performance from administrative colleagues. So once a year during my first few years, I assembled the professors who had served on the search committee that hired me to ask them how I was doing and what suggestions they had about how I might improve.

Some of these professors were interviewed for the Summer 2004 issue of the Rollins Alumni Record and were quoted in a series of articles on my retirement. I could barely believe their kind comments.

Larry Eng-Wilmot, professor of chemistry, said “her Rollins legacy …is a marvelous set of visionary and indelible fingerprints that will always lead and encourage us to be better learners, teachers, scholars, citizens and people.” Jim Small, a biology professor, added that bringing me to Rollins “is one of the most important highlights of my career here.”

In 1994, I received my first and only evaluation by the trustees. The chairman, banker Mike Strickland, praised my vision and complimented my ability to “take command of any situation.” He said that he appreciated the strategic planning process I led, and praised the expanded composition of the board and my relationship with it. He was pleased with our fundraising, especially for endowed chairs.

I enjoyed being called “Prexy” because that was the

affectionate title students had given Hamilton Holt.

Being compared with Holt was a great honor, since

he brought national attention to the college as an

educational innovator and champion of world peace.

From the earliest days of the search process through the initial planning years of my presidency, I constantly considered how to generate enthusiasm for a fundraising campaign at Rollins that would be unprecedented in size and scope.

My focus was to start by building a culture of excellence. I wanted every area to participate in this effort — operations, facilities, teaching, research, student life, administration, philanthropy, governance and even landscaping.

Yes, landscaping. I had learned that attractive landscaping produces curb appeal and communicates a commitment to excellence in all other aspects of an institution.

Architecture plays a similar role in defining a campus. So I spent time with architects and carefully reviewed their plans and drawings. I also sought advice from Jack Lane, a professor of history and the college’s historian, who advised us on traditional styles and the original purpose of facilities.

I enjoyed the process and, as a result, was able to redirect projects that had been poorly designed for the needs of the college.

We also scoured the budget for places where we could save money. Rollins had a pair of night programs: The Hamilton Holt School, which was highly esteemed by our community, and a campus on the Space Coast in Brevard County.

Professors were immensely proud of the Hamilton Holt School — which offered evening degrees to nontraditional students — and many taught there. I was especially drawn to Holt students because they, as I had, usually juggled the demands of college with raising children and working.

However, the Brevard campus was more difficult to justify. Its distance made it hard to manage and the revenue wasn’t commensurate with the costs. Consequently, I had the sad responsibility of closing that program.

The college also had a variety of graduate degree programs, the most highly acclaimed of which was the Roy E. Crummer Graduate School of Business. I found the professors hardworking, highly intelligent and loyal to Rollins. I had many friends among the Crummer faculty, and was honored that many of them dedicated their books to me.

My attachment to the overall faculty grew as I got to know the professors as individuals. Yes, some were quirky, and some were hostile to those whom they viewed as bureaucrats.

But from the time I started, even usually uninvolved faculty agreed to participate in strategic planning. After all, they’d been asking the same questions as I had. How do we improve Rollins’ reputation? How do we generate more resources?

I relied especially on three people I had brought into my administration. First there was Lorrie Kyle, a Rollins graduate who held a Ph.D. from Vanderbilt, who was my brilliant and accomplished executive assistant.

There was also George Herbst, one of the few financial vice presidents able to build good relationships with faculty; and Charlie Edmondson, a longtime history professor who made an excellent provost and academic vice president. Driven by a commitment to high standards, Charlie went on to become president of Alfred University in New York.

To improve the college’s academic standing, we focused first on attracting a stronger group of students. This allowed us to be more selective in admissions. We also recognized that institutional prestige was, in part, based on the quality of the professors and emphasized the importance of endowed chairs to our supporters.

Every year, I proudly exhibited the publications of faculty members in my office. I thought it was important as well to personally and informally encourage excellence among professors, students and staff. I believe the effort was appreciated.

When Jonathan Miller, the college’s director of libraries, left to take a similar position at Williams College, he wrote me a note saying: “I have been at Rollins for almost 11 years now and have really appreciated your support, advice and friendship. [You] … showed more interest in the progress I was making on my dissertation than anyone else and you were always very generous with your advice and counsel to me.”

A president can also contribute to an institution’s reputation and visibility by serving as a “public intellectual.” During my presidency, I wrote and published 46 articles and four books with a focus on leadership, governance and fundraising.

I was also frequently quoted in national magazines and newspapers, and served on the boards of many higher education associations. During my presidency, I received three honorary doctorates and 26 awards.

The high point for Rollins in our quest for quality and recognition was when U.S. News & World Report raised our ranking among Master’s Colleges in the South from sixth to first. I’ll never forget the excitement of a group of alumni, back on campus for a reunion, who came flooding into my office to celebrate.

Faculty complained that the college lacked a collegial and intellectual climate. I believe that these are worthy goals, but that they are the responsibility of the faculty. However, I felt that I should do my part and launched an annual square dance. To provide opportunities for intellectual engagement, I convened lunchtime discussions on serious topics and faculty research.

An intellectual high point for me and for the college was the 1997 conference that I planned and hosted together with the College Board, a not-for-profit organization formed in 1899 with the goal of expanding access to higher education.

The conference, which was titled Toward a Pragmatic Liberal Education: The Curriculum of the Twenty-First Century, was based on the previously mentioned colloquy hosted by President Holt in 1931. Our conference attracted 200 presidents and scholars from 50 colleges and universities.

One participant called the experience “a feast for the mind.” Later that year, the College Board produced a book with chapters by conference presenters: Education and Democracy: Re-imagining Liberal Learning in America.

$100,000,000? IMPOSSIBLE!

During my first year at Rollins, I surprised the trustees by proposing an ambitious “Campaign for Rollins” with the goal of raising $100 million. Because the college had been financially challenged since its founding, there was plenty of skepticism. As evidence, some trustees cited the prior campaign, which concluded five years earlier having raised just over $40 million.

However, after much discussion and encouragement, the trustees agreed to the goal. One vivid recollection I have is, halfway through the campaign, seeing a senior staff member standing in my doorway saying, “The campaign is over. We’re out of prospects.” Well, we didn’t run out of prospects and the campaign wasn’t over.

When we announced to a gathering of campaign contributors that we had exceeded our goal and raised $160.2 million, there was much jubilation, as you can imagine. Better still was the fact that alumni had contributed 52 percent of the total.

This fact was especially pleasing to me, because early in the campaign I had been told by a staff member that while graduates loved their alma mater, they would never contribute any money.

Forty-nine percent of the funds were designated for the college’s endowment. I had made endowed chairs a high priority, understanding these to be a mark of quality in higher education. We also secured a $10 million gift for an endowed chair for the president — about which I’ll elaborate shortly.

We eclipsed the goal because of our skilled and indefatigable staff. Vice President Anne Kerr went on to became president of Florida Southern College and put her considerable skills to work remaking the school in Lakeland. David Collis, assistant vice president of development, became president of the AdventHealth Foundation and has done an exceptional job of attracting support.

The campaign enabled us to buy and develop some important nearby properties. We built a commercial center and a parking garage in downtown Winter Park designed to generate revenue, which it has.

And we built the beautiful McKean Gateway, the first formal entrance to the college. A visiting architect later said the Gateway looked as though it had stood for a century or more.

We also built or renovated more than 30 academic, athletic and residential facilities, including a much-needed President’s House, now called the Barker House. To avoid potential controversy, I purposely didn’t occupy the house during my tenure. (Harland and I had bought a modest residence in 1990, when we moved to Winter Park.)

Overall, I was thrilled and relieved that I had done what I promised I would do: build a strong reputation for quality and a healthy financial foundation for future success.

I donated funds to name a waterside gazebo for my husband (Harland’s Haven) and a cascading water fountain for me (Rita’s Fountain). Both these gifts gave me great satisfaction.

An exciting opportunity arose in 1996, about halfway through my presidency, and made me both pleased and nervous. University of Miami President Tad Foote nominated me for the presidency of the American Council on Education (ACE), a Washington, D.C.-based organization that advocates for the nation’s colleges and universities.

It was a great honor, so I assented to an interview. The search committee was comprised of distinguished academics and presidents. And although I had an excellent interaction with them, I made it clear that I was in a “golden moment” at Rollins and couldn’t leave at that time.

Leaving would have been difficult to do in any case. Trustee Charlie Rice sealed my decision when he said that if I left, he would take back his campaign gift, which was at that time more than $1 million. Thus ended my dalliance with the ACE, exciting as it was.

One of the factors in the U.S. News & World Report’s evaluation of colleges and universities is the size of the endowment. At Rollins, endowment funds brought in by the campaign, coupled with a large bequest from alumnus and trustee George Cornell, made a huge difference.

The college’s endowment, $39 million when I arrived in 1990, grew to more than $200 million by the start of the new century. That was partly the result of our successful campaign, but there was more to it. Here’s the story of George’s gift.

Each year, when George returned from vacation up North, he came to talk to me about the same issue. His advisors were constantly urging him to establish a foundation. What did I think?

I always responded that the decision was entirely up to him. But I also reminded him that when the original philanthropists, their relatives and advisors were gone, foundations often changed direction to follow the interests of the remaining board members.

George never set up a foundation. And as a result, Rollins received more than $105 million when he died, shortly after the conclusion of the campaign. If he had formed a foundation, its board would have no doubt dispersed the same funds over a wide array of beneficiaries.

One of the first people I told when I decided to retire was George. A man of few words, he said, “We’ll miss you.” In fact, it was George who had made the gift of an endowed chair for the president. He asked the solicitor two questions: “Will this gift keep Rita here?” And, “Will this gift help recruit her successor?”

Throughout my presidency, the person who provided me unqualified support was my husband, Harland, who for years had been teaching courses about the operations of higher education, including the president’s role. He loved the idea that now he had an inside view.

After a year of traveling from Winter Park to teach at the University of Miami, he retired and produced some of his best scholarship. Harland was well liked by everyone. He was funny, smart and a great conversationalist. People coveted the opportunity to sit next to him at dinner.

Harland joined me in explaining to our families, especially the children, why it was important for our behavior, public and private, to be above reproach. It was he who gently reprimanded me one day for jaywalking across Park Avenue, reminding me that everything I did — even seemingly minor things — reflected on the college.

Harland often accompanied me to help handle emergencies on campus. We had lawsuits, student deaths, alcohol poisonings and car accidents. You name it, and we dealt with it. It was all part of the job.

RITA’S ROLLINS RENAISSANCE

I was surprised and delighted by the tributes and gifts I received when I announced my retirement in 2004. Roy Kerr, senior professor of language, began referring to “Rita’s Rollins Renaissance.”

At a ceremony in the Knowles Memorial Chapel, Maurice “Socky” O’Sullivan, distinguished professor of English, presented me with a unique book, Teaching in Paradise, that contains articles by Rollins professors about their love for and approach to teaching. The book is dedicated to me, and I treasure it.

John Hitt, then president of the nearby University of Central Florida, sent a message that I appreciated. He wrote: “When presidents do their jobs really well, they not only transform the lives of students, they transform the lives of their institutions, and you have done that for Rollins.”

The expressions of affection and gratitude from faculty, alumni, students, community leaders and friends around the country made my departure both easier and more difficult.

Soon after my announcement, I received a note from Robert Atwell, longtime president of the American Council on Education. He wrote: “…You have been a model of principled leadership at the campus and nationally. I have often cited you as someone new presidents should emulate.”

In my book Legitimacy, I examined the challenges of a college presidency for those who lack a traditional academic background. I also discussed presidents who’ve been unsuccessful despite looking great on paper. I identified the threats to legitimacy, such as misconduct, inattentiveness, grandiosity, lack of cultural fit, management incompetence and erosion of social capital.

Throughout my presidency, I was vigilant in seeking legitimacy and avoiding the pitfalls I had highlighted. All my experiences, good and bad, had strengthened my capacity for empathy, confidence and resilience. The example of my family — the dogged determination to be and do the best they could — stimulated my development of those values.

I’ve had a long time to consider my mother’s question about my evolution from shyness to confidence. Her own ambition and that of her family had a lot to do with it, as did the many mentors who, along the way, helped me define myself.

Businessman Frank Barker, chair of the trustees, worked out a designation for my endowed chair that I could use in retirement (Cornell Professor of Leadership and Philanthropy).

All my experiences, good and bad, had strengthened

my capacity for empathy, confidence and resilience.

The example of my family — the dogged determination

to be and do the best they could — stimulated

my development of those values.

The trustees also established the Bornstein Award for Faculty Scholarship, which is presented each year at commencement. This award, which comes with a $10,000 stipend, is special to me because it recognizes faculty scholarship and its role in extending Rollins’ reputation. It reflects my values and, for me, is always a commencement highlight.

In addition, the trustees established the Rita Bornstein Leadership Forum. And I was mightily surprised and delighted when I learned that a new student residence hall on Lake Virginia was to be named “Rita Bornstein Hall.” To top it all off, the Winter Park Chamber of Commerce honored me as “Citizen of the Decade.”

When Harland died in November 2004, I invited Hoyt Edge, professor of philosophy, to preside at the celebration of life that we held on the lawn extending from Harland’s Haven.

English Professor Barbara Carson read a poem by W.H. Auden, “Stop all the Clocks,” and members of my family and various trustees offered remembrances. We played a prerecorded electronic composition by Per, Harland’s son.

In my comments, I noted that Harland was the smartest, funniest and sexiest person I had ever known. I missed him and, feeling lonely, wrote these words: “The moon is round and orange, it has an Asian face and…wings. ‘Oh, look at that.’ But you are not here to share my enchantment.”

RETIRED … SORT OF

My decision to retire was largely driven by Harland’s poor health. He died just four months later, and I was glad to have that time with him. I had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, but didn’t want people to feel sorry for me and didn’t talk about it.

When I told my family that I was retiring, Ariel, one of my daughter’s twin girls, said, “But, Grammy, then you won’t be important anymore.” Perhaps not in the same way, but I did plenty of planning to ensure an active post-Rollins life.

This was important to me. I had never learned to play golf or bridge and had no hobbies but reading and writing. I was concerned about adapting to a nondemanding, low-energy existence.

I fulfilled my term on two corporate boards, but remained on three nonprofit boards: the Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts, the Winter Park Health Foundation and the Parkinson Association for Central Florida.

Retirement has turned out to be anything but quiet or uneventful. I moved to The Mayflower Retirement Community, close to Rollins, and found many opportunities for physical activity, intellectual challenge, community involvement and family interaction.

I’ve written an occasional opinion piece for the Orlando Sentinel, and continue to meet with a few young men and women whom I’ve been mentoring for years. I host a monthly discussion group made up of 16 diverse and politically active people from the community. At this writing, we’ve been meeting and talking for about 15 years.

I’m also involved in a discussion group consisting of three other retired Rollins professors, and started another group called “Forum for Ideas” at the Mayflower, to which I invite professors, poets, businesspeople and others to make presentations. Lately, we’ve been meeting over Zoom.

In October, I donated $100,000 to establish the President Rita Bornstein Archival Records Endowment. Its purpose will be to support the digitation and preservation of archival records housed in the Olin Library’s Department of Archives and Special Collections.

I remain drawn to the possibilities of innovation and change in education. Why, you may ask?

To assure that our educational institutions and their leaders provide opportunities for every student to find a path to a successful future. So that even a young, insecure girl from a broken family, with nothing to hold on to but the faint idea of a meaningful future, can launch her life.