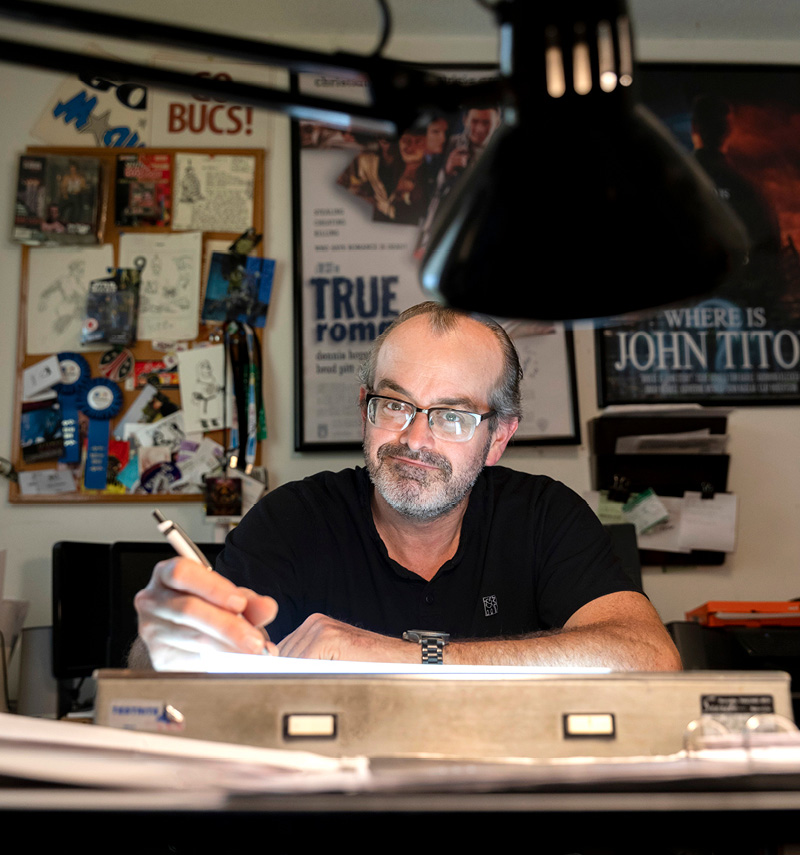

Photography by Rafael Tongol

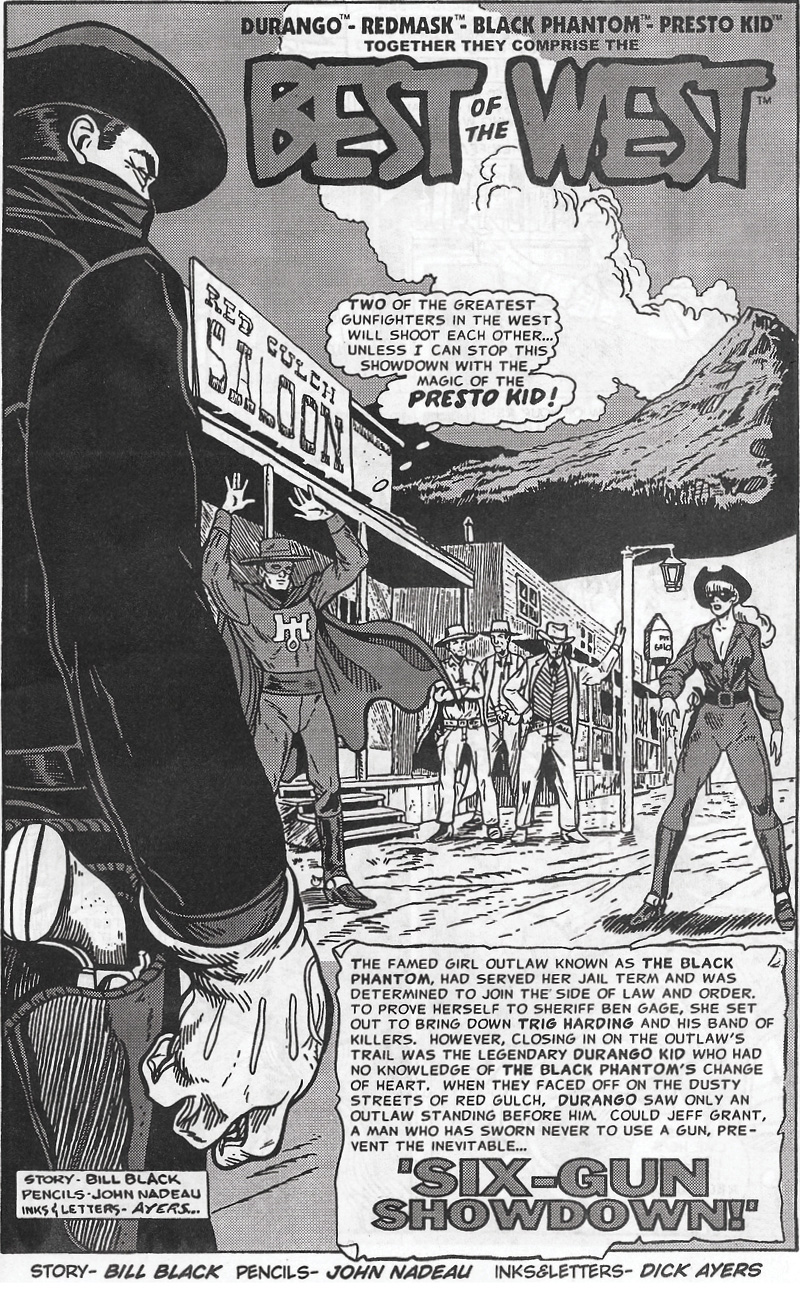

John Nadeau was a senior at Winter Park High School when he landed his first professional gig as a comic book artist. He penciled a western called Best of the West for Americomics, a Longwood-based independent publisher that specialized in Golden Age-style adventure and superhero titles.

He thought, in retrospect, that his 1989 effort looked awful. Luckily, he says, veteran comic book inker Dick Ayers took the penciled pages and “cleaned them up considerably” by adding depth, weight and richness with his pen and brush.

“I didn’t actually see it in print until I was away at college,” says Nadeau, who admits that his high school “cool quotient” increased exponentially at having a forthcoming professional credit. “They mailed a copy to me. My excitement at doing anything at all eclipsed the fact that I didn’t think it was very good.”

Comics, for the uninitiated, are often drawn in pencil. Then, for purposes of reproduction, another artist embellishes the pencils with India ink. A good inker brings his or her own flair to the penciled pages. Ayers — who in the 1960s had been the primary inker on the legendary Jack Kirby’s artwork for Marvel Comics — was one of the greats.

From Best of the West through Aliens and Star Wars, Nadeau, 49, has penciled and inked his way into the upper echelon of comic artists through his mastery of complex, futurist machinery and a vivid imagination that conjures up gigantic space colonies in which cities are enclosed in cylinders that float through deep space.

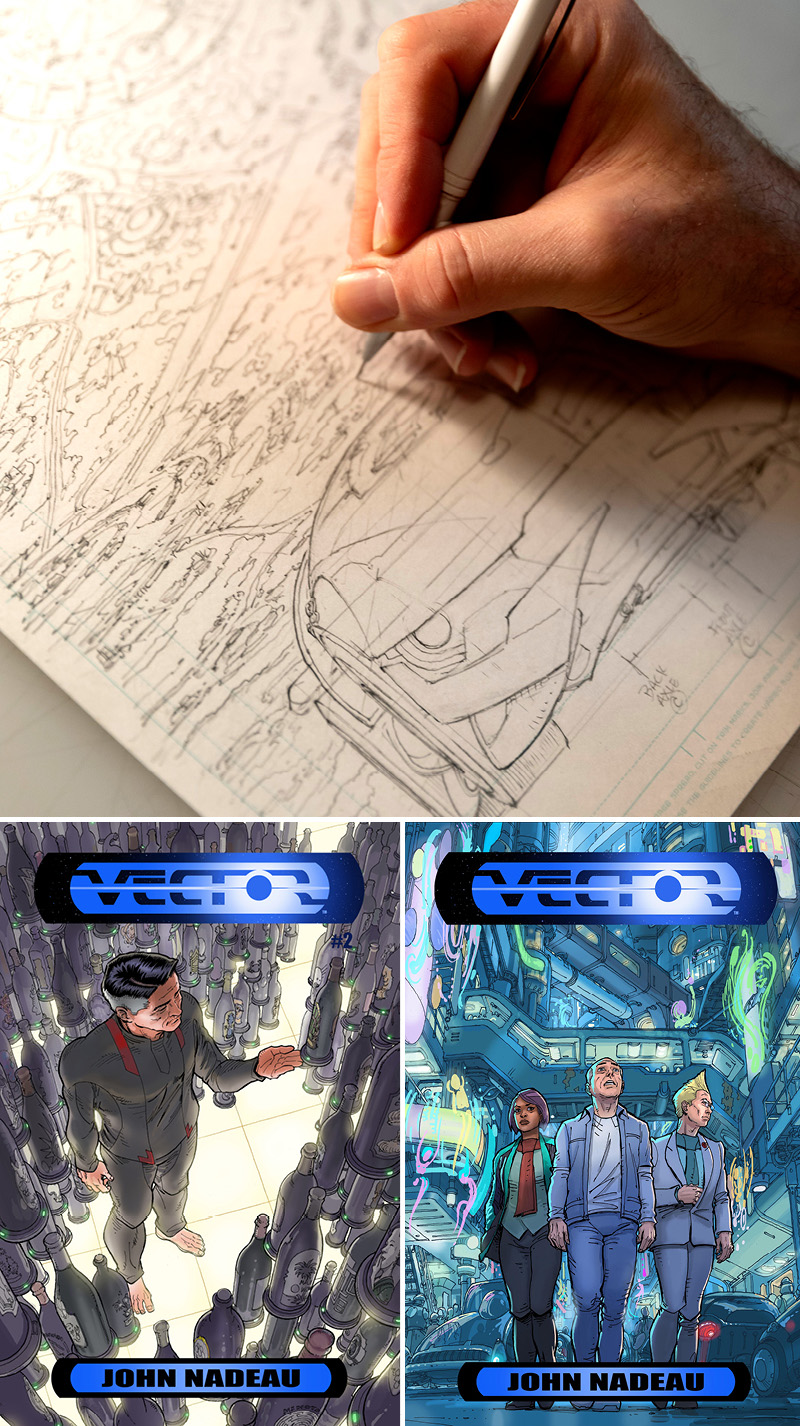

Such a megalopolis is the setting for a recent series of self-published comics called Vector, which combine the seemingly disparate worlds of science fiction with fine-art smuggling. The stories are fun, but the real treat is Nadeau’s art, which depicts the self-contained colony and its denizens in exquisite detail.

“I was that kid who drew all the time,” recalls Nadeau, who as a child moved to Maitland from Syracuse, New York, with his family. “In middle school, I discovered comics. And I decided: ‘I want to do that.’”

More specifically, Nadeau discovered the work of British-born comic artist John Byrne, who in the late 1970s was teamed with writer Chris Claremont on Marvel Comics’ The X-Men. Byrne and Claremont revitalized the title and made its Canadian character, Wolverine, among the most popular in Marvel’s publishing history.

If Marvel (whose characters included Spider-Man, the Hulk and the Fantastic Four) and D.C. (whose characters included Superman, Batman and the Justice League of America) comprised the comic book equivalent of the major leagues, there were some far-more-accessible minor-leaguers doing good work as well.

Nadeau connected with one of them, Americomics, when he met publisher Bill Black at a comic book convention at a hotel on Lee Road. Black was already an industry notable, having drawn stories for Warren Publishing’s popular black-and-white horror magazines Creepy and Eerie in the 1960s.

Those now-defunct periodicals featured the work of Frank Frazetta, Reed Crandall, Joe Orlando, Wally Wood and others who were considered masters of the craft. Several had made their names at E.C. Comics, the company that published stories so gruesome that a U.S. Senate subcommittee on juvenile delinquency met to discuss “the problem of horror and crime comic books” in 1954.

(As with rock ‘n’ roll, though, the grownups just didn’t get it. Still, the ensuing brouhaha pushed publishers to offer tamer — or, to be honest, duller — material until the superhero genre really took flight in the early 1960s. Some comic artists subsequently came to be regarded as rock stars, and “sequential art” as a discipline began to be regarded seriously.)

Nadeau showed Black his portfolio, and shortly thereafter began getting scripts to illustrate. By that time, the comic book industry was no longer driven by single-copy sales at those ubiquitous revolving racks at drug stores (Hey Kids! Comics!) but through direct purchases by comic book retail shops.

While having fun, Nadeau nonetheless recognized the need to earn a living and drifted away from comics, where creators remained poorly paid despite their increasing panache. He enrolled at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach to pursue study as an aerospace engineer. “I realized, though, that I just didn’t have the math skills,” he recalls. “I hit the wall at differential equations.”

Short and frustrating stints at Embry-Riddle and later Florida State University confirmed the futility of the effort. “The more I discovered my ineptitude in mathematics, the more I wanted to go back to comics,” says Nadeau, who began drawing again for Americomics in 1991.

The title he was assigned was Femforce, an “all-girl” team of shapely superheroines that included some new characters and some that dated from the 1940s and had been resurrected from public domain. The characters were pure eye candy for young male readers, but there was a certain nostalgic quaintness to the series — which is still being published despite its political incorrectness.

By the late 1990s, Nadeau had moved on to a galaxy far, far away with a series of Star Wars comics for Dark Horse, an Oregon-based publisher. A one-off issue that featured bounty hunter Boba Fett was voted “Best Original Star Wars Comic” by readers of Star Wars Galaxy, an officially licensed magazine that focused on collectibles related to the film series.

Nadeau also drew Aliens-themed mini-comics, which were packaged with action figures from the screamworthy science fiction film, as well as several issues of Wolverine for Marvel and Green Lantern for D.C. Most comic artists love drawing iconic superheroes. But Nadeau was really more suited for the elaborate machinery and horrifying bug-like monsters in Aliens.

Later, as the comic book industry slumped, Nadeau began to expand his horizons and completed a degree in film production technology from UCF. He also scripted and produced a low-budget feature film — never completed — which he describes as “a horrible idea involving pizza delivery drivers who get involved with murderers.”

Discouraged, Nadeau returned again to drawing and found an outlet for his love of structures and contraptions as a commercial artist and architectural renderer. He worked for various clients in Central Florida and around the world, including GoCovergence, HHCP Architects, OBM International, Simiosys, Sonesta, the Walt Disney Company and others.

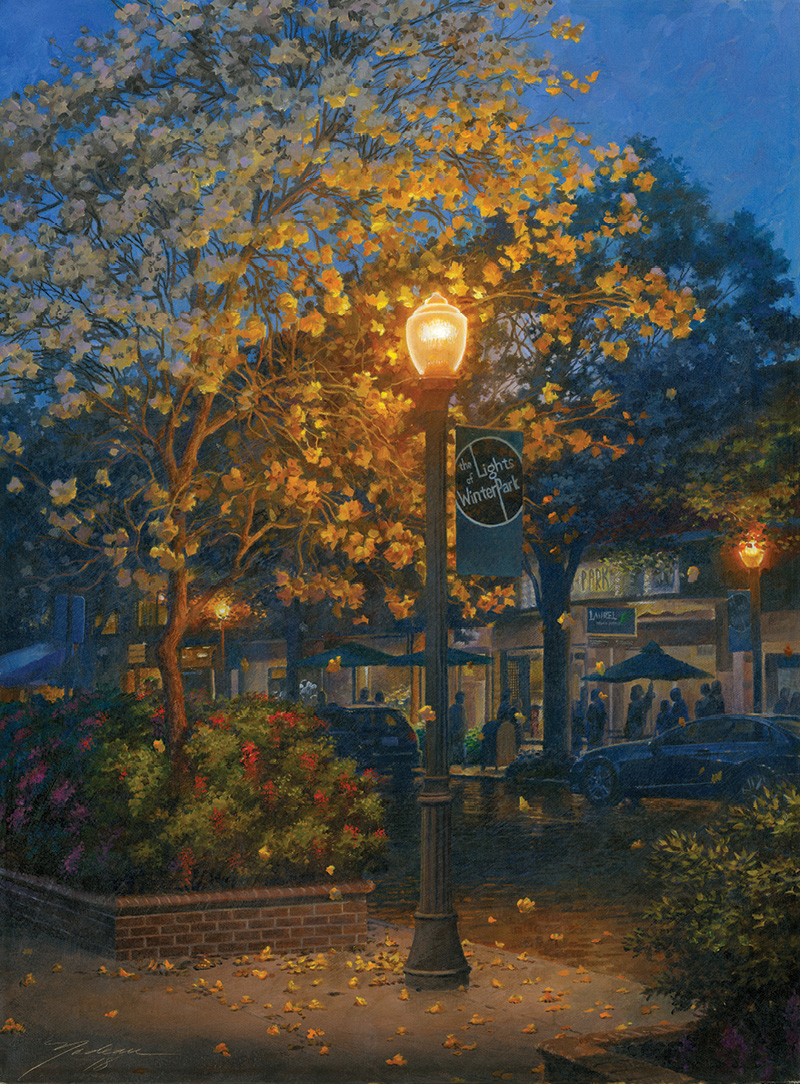

He has subsequently sought to enter the fine art world by honing his painting skills through classes at the Crealdé School of Art. In 2018, he began doing oil paintings for The Art of Disney Galleries, and his creations have been featured in several one-man shows — including one earlier this year at Winter Park City Hall.

But for Nadeau, the lure of comics remains strong. In 2017, he co-wrote and illustrated the series Murder Society for the Dark Horse anthology Dark Horse Presents. And two issues have been printed, but not yet distributed, of Vector, set in the meticulously rendered space colony.

What’s the future of comic books? “I’m the last person to ask,” says Nadeau, who confesses that he enjoys creating comics but is generally ambivalent about the business model that keeps the industry afloat. “I suppose everything is going digital.”

Well, hopefully not everything. Nadeau is currently hard at work — using a pencil and illustration board — on the third issue of Vector. “Making comics is better than making movies,” he says. “You have the scope of a big-budget movie, but you don’t have to depend on other people — and you have complete control.”

– Randy Noles