I thought we were going to make a statement when we opened a location on Park Avenue,” says Scott Hillman, president of Fannie Hillman + Associates, one of the city’s largest real estate companies. “You could say this move has surpassed my expectations.”

Hillman, a Winter Park native, was familiar with much of the history surrounding the building in which his nearly 40-year-old agency opened an office in 2019. But the more he found out, the more intriguing it all became. It’s a little complex, with some twists and turns, but please bear with us as we try to sort it out and connect the dots.

In 1917, industrialist Charles Hosmer Morse — who since 1904 had owned most of the undeveloped property in Winter Park — erected a brick building that today encompasses the addresses 122, 128 and 132 South Park Avenue for a cost of $15,000.

The Winter Park Land Company, incorporated that year by Morse as the city’s first real estate firm, occupied 132; a reading room for the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), whose mission was supported by Morse, occupied 128; and the Baby Grand Theater, the city’s first movie-house, occupied 122. Residential apartments were upstairs.

The Baby Grand, which seated 336 people, began showing silent films accompanied by piano in a large open space at the building’s rear. The debut film was a melodrama called Stolen Paradise featuring Ethel Clayton and Edward Langford. Tickets cost a dime. The venue also hosted vaudeville shows and community meetings.

The theater was originally operated by Rollins College and University of Virginia School of Law graduate Braxton “Bonnie” Beacham Jr., manager of Grand Amusement Company (GAC). The family enterprise appears to have been founded around 1913 by the younger Beacham’s parents, Braxton Sr., who was mayor of Orlando from 1904 to 1905, and Roberta, a socially active patron of the arts.

GAC managed several other movie houses in Central Florida, such as the Grand, the Lucerne and the Phillips Theater (owned by Dr. Phillip Phillips, for whom today’s Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts is named).

But the iconic Beacham Theater, which operates today as a nightclub, wasn’t opened until 1921. Although the Baby Grand is often said to have been the Beacham’s “little sister,” the Park Avenue theater, in fact, predated the familiar Orange Avenue landmark by several years.

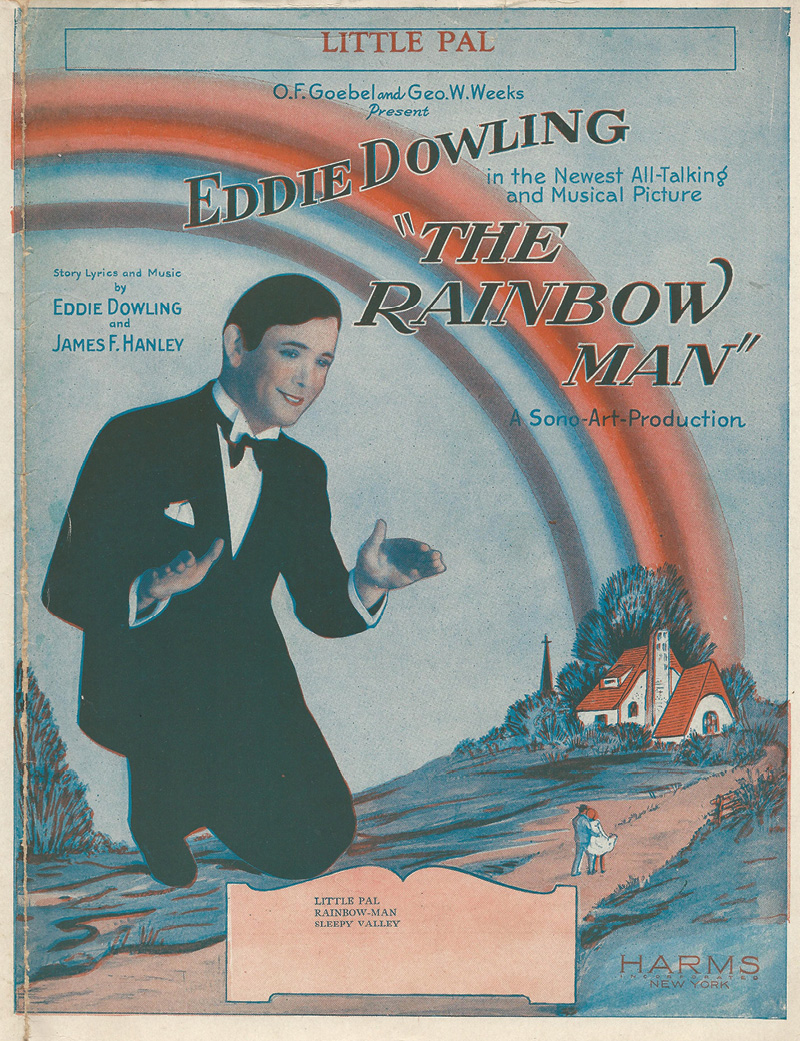

The Baby Grand, now under the management of E.J. Sparks of Orlando Enterprises, was remodeled in 1928 with a $10,000 pipe organ and Vitaphone and Movietone equipment to accommodate sound pictures. Its first talkie was 1929’s The Rainbow Man, a pre-code musical starring Eddie Dowling and marking the film debut of George “Gabby” Hayes.

By then, the Baby Grand was owned by Paramount Pictures. (In fact, many movie theaters were owned by motion picture companies until 1948, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the practice was a violation of antitrust laws.)

Winter Park’s first theater closed in 1940, when the 850-seat Colony Theater, also managed by GAC (and today a Pottery Barn retail outlet) opened across the street.

The Baby Grand’s last feature — for the time being — was I Take This Woman starring Spencer Tracy and Hedy Lemarr. In 1947, however, it mounted a short-lived comeback showing primarily westerns and second-run films before closing for good the following year.

It must also be said that the Baby Grand was restricted to whites only. The west side of Winter Park had its own movie theater, The Famous and later The Star, which operated at least through the early 1960s. The theater showed films with all-Black casts as well as second-run mainstream features.

In 1950, the Baby Grand space was remodeled for the Winter Park Land Company, which relocated from two doors down. The theater area, however, remained a large open space with a few desks scattered about. It was in this location where the company celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2017.

In the meantime, business was booming for Hillman, whose main offices are nearby at 205 West Fairbanks Avenue. The company was founded in 1981 by Scott Hillman’s mother, Fannie, previously the top producer at Don Saunders Realty in Winter Park.

Fannie Hillman’s son, a graduate of Florida State University, joined the following year and was named president in 1994. The company’s namesake, now a spry 86 and a resident of the Mayflower at Winter Park, “still checks in to see how we’re doing,” says her hard-charging offspring, whose lengthy civic resumé includes a stint as junior varsity football coach at Winter Park High School.

Today, Hillman oversees an operation that employs 85 agents and racked up more than $300 million in gross sales in 2019. “For years, though, I had a vision of being on Park Avenue,” says Hillman, who adds that he redoubled his expansion effort as his company’s 40th anniversary approached.

Hillman bought the assets of the Winter Park Land Company — perhaps the oldest continually operating real estate company in Florida — from the owner of both the business and the building, the Elizabeth Morse Genius Foundation.

Genius was the only daughter of the legendary Morse (1833–1921) and the grandmother of Jeannette Genius McKean (1909–1989), whose husband was former Rollins College President Hugh F. McKean (1908–1995).

An artist and a businesswoman, Jeannette Genius McKean began the foundation — which today supports the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art and other good causes — in 1959. She was also president of the Winter Park Land Company and operated the Center Street Gallery at 132 South Park Avenue, which was the original location of the Winter Park Land Company.

The foundation still owns the building that Charles Hosmer Morse built. But Hillman says he hopes to find ways to highlight its significance as home to both the city’s first theater and its first real estate office. A visitor can see that he’s still in awe of his surroundings, pointing out the quirky architectural features — such as a pressed tin ceiling — in the theater area.

Says Hillman: “I want to get a historic marker for this building.” Such a marker would celebrate the past, but Hillman is certain that there’s more history to be made at 122 South Park Avenue South.