When classes reconvene at Rollins College in a few weeks, Poetry 101 with Billy Collins won’t be on the schedule. It’s not as though it ever really was, strictly speaking. The relationship between the college and the former two-term U.S. poet laureate was never that cut and dried.

Dubbed by The New York Times as the most popular poet in the country and inducted four years ago into the prestigious American Academy of Arts and Letters alongside the likes of Joan Didion and Kurt Vonnegut, Collins has probably done more to engage people with poetry than any other American scholar-practitioner in recent memory.

He’s a 79-year-old native New Yorker with a deadpan delivery, a passion for jazz and a flair for unpacking everyday moments by pairing shrewd humor with habitual wonderment.

A reviewer once complimented Collins for “putting the fun in profundity,” a turn of phrase that will serve as the blurb on his 13th book of poems, Whale Day, to be published in September.

Soon after moving to Central Florida 12 years ago, Collins was appointed senior distinguished fellow at the Winter Park Institute at Rollins College, which brought luminaries such as Maya Angelou, Ken Burns, Gloria Steinem, Jane Goodall, Garrison Keillor, Itzhak Perlman and Sir Paul McCartney to campus for lectures.

Having the likeable Collins in residence to recruit fellow creatives and make regular appearances himself was something of a coup for a small liberal arts college.

Yet, however prestigious its speakers or distinguished its fellow, the Institute was a financial drain, even after it began charging admission in 2016. When belt-tightening became a priority — as it did five years ago, when President Lewis Duncan resigned — Collins was told that his contract wouldn’t be renewed.

After a quiet community protest, he was rehired by incoming President Grant Cornwell, only to be let go again more recently when the Institute itself was disbanded as part of a college-wide response to the financial hit expected from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The same fate befell Winter with the Writers, an annual event that brought nationally recognized authors to campus to tutor students and present readings.

Administrators also made a sweeping reduction of salaries and benefits and reduced the college workforce by 8 percent, so the programs and the poet aren’t the only budgetary casualties — just the most visible ones outside campus.

Though he deserves better treatment, Collins, an international figure whose books are always New York Times bestsellers, will survive the financial blow. The loss is all ours.

It’s sad to witness the disappearance of initiatives so intertwined with the heart and soul of Rollins — past, present and future. The lectures echoed the legendary Animated Magazine, which ran from the 1920s through the 1960s and brought the likes of Edward R. Murrow, James Cagney, Mary McLeod Bethune and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings to Winter Park.

Apart from that, such programs served the present by showcasing world-changing role models who underscored the college’s mission: to imbue the students of today with a sense of global citizenship for tomorrow.

There are glimmers of hope. Gail Sinclair, the Institute’s outgoing executive director, suggests that the community itself might bring back the lecture series. A Rollins writing class based on a downsized version of Winter with the Writers has been approved.

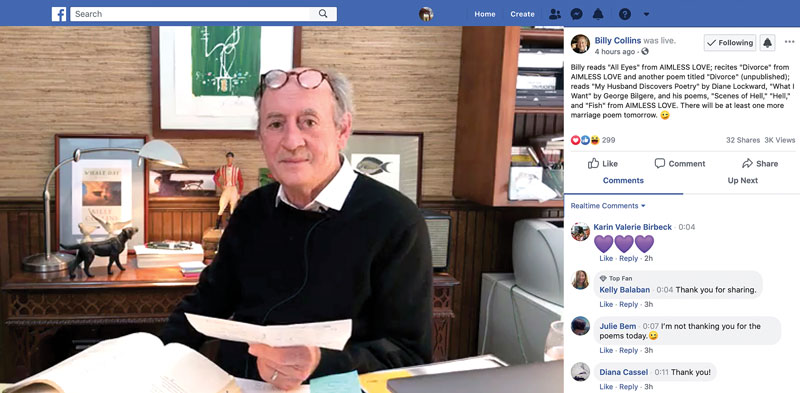

And six days a week at 5:30 p.m., Collins sits down at a desk in the office of his home in a lakeside Winter Park neighborhood near the campus, with a shifting sheaf of papers and a pile of weather-beaten poetry books in front of him.

For the next 20 minutes or so, via Facebook, he conducts what feels like a late-night talk show with a literary flair. His wife, Suzannah, suggested the idea of a happy-hour poetry reading for his fans.

There’s always a theme — haiku one day, poetry about travel another. More than one broadcast has been devoted to verse related to jazz, complete with mood music from Collins’ own extensive collection. Sometimes he reads his own works, sometimes those of his contemporaries. Meanwhile comments from his growing band of listeners scroll by, attesting to the poet’s global reach — here a hello from Ida Valley, New Zealand, there a quip from West Cork, Ireland, just beneath a question from Kutztown, Pennsylvania.

Collins sees the virtual appearances as a counterpoint to a politicized, hall-of-mirrors modern-world reality — “this massive grid of interconnected voices and tweets and lies.” By contrast, he says, a poem represents something honest, concrete — “a world sovereign unto itself. It’s just you and me here.”

Just you and Billy and Poetry 101. At least that much hasn’t changed.