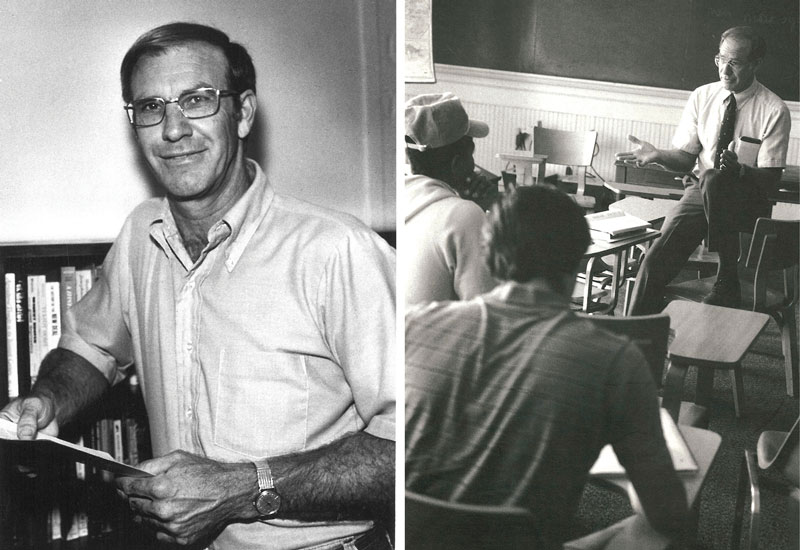

Jack C. Lane began his academic career at Rollins College nearly 57 years ago as a specialist in military history. “Most military history is written by people with a very patriotic view toward the military, so I thought there needed to be another perspective,” he says.

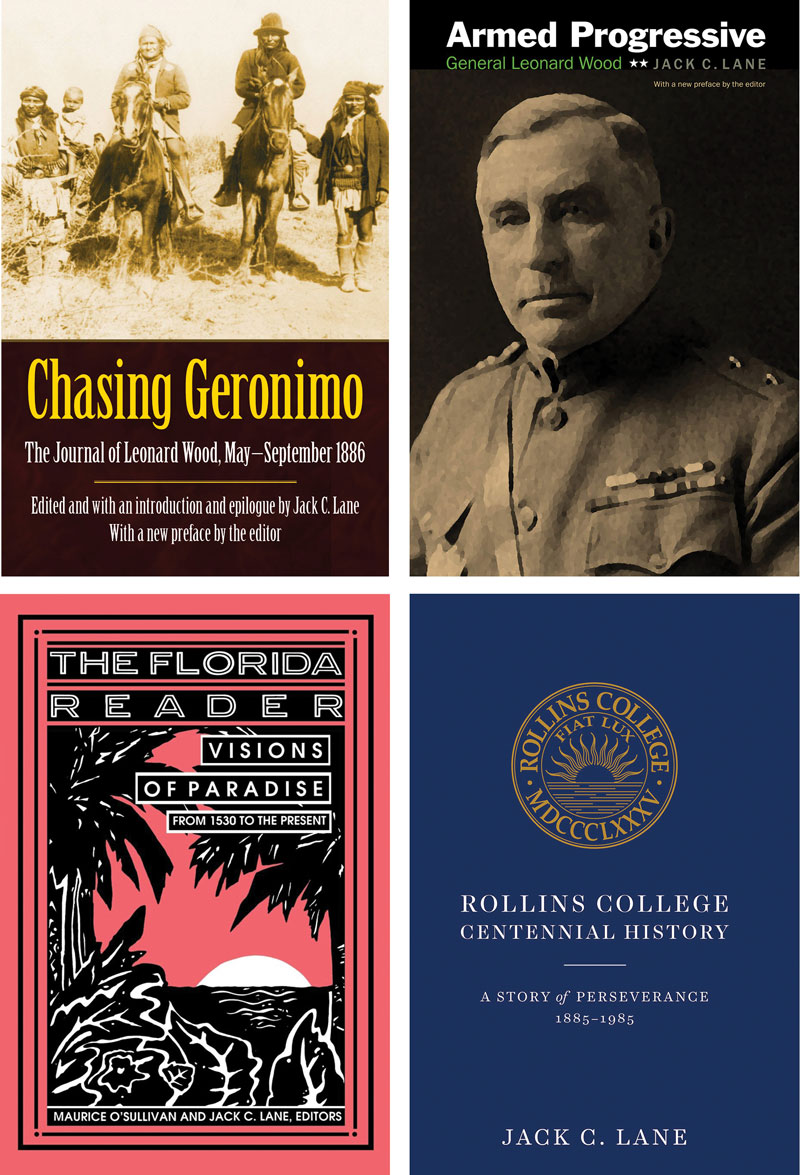

Lane’s dissertation and his scholarship have included explorations of American foreign policy. And he would later write several well-regarded books on military topics, including Chasing Geronimo: The Journal of Leonard Wood, May–September 1885 (1970) and Armed Progressive: General Leonard Wood (1978). Both books have been reprinted several times.

Wood (1860–1927) was certainly a compelling subject. In 1885, he was an assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army and was stationed with the 4th Cavalry at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. He participated in the last campaign against Geronimo in 1886, and was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1888.

Alongside Teddy Roosevelt, Wood commanded the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War. Later, he became Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, Military Governor of Cuba and Governor General of the Philippines. He was a leading candidate for the Republican presidential nomination in 1920.

But Lane’s interest in military matters began to wane. Even more fascinating — if, thankfully, not nearly as bloody — was Winter Park and Rollins College. When the late Thaddeus Seymour was appointed president of the college in 1979, he named Lane “college historian” and asked him to begin writing a centennial history to be published in 1985.

“So, I started getting into educational history, higher education,” says Lane, a native of Texas with a master’s degree from Emory University and a Ph.D. from the University of Georgia. Both advanced degrees are in American history.

“I wanted to see where Rollins fit in all of that,” he says. “I saw some opportunities there, so I wrote about it. And then just became interested generally in American cultural history and so sort of drifted away from military history.”

Winter Parkers from that time forward have been the beneficiaries of what Lane describes as his scholarly “short attention span.” His account of the college’s history, as it happened, was completed in 1985 but, due to budgetary constraints, wasn’t published until 2017.

President Grant Cornwell, who was hired in 2015, read the languishing manuscript — which Lane had posted online — and knew it had to see the light of day.

Better late than never. Rollins College Centennial History: A Story of Perseverance, 1885–1985 was no dry academic tome. Instead it was filled with eccentric characters, near-disasters, daring innovations and heady achievements. And the crackling story was told with the combination of a storyteller’s zeal and a historian’s rigor.

Chapter headers offer confirmation that Lane was granted carte blanche to tell the roller-coaster tale like it really was: “The Struggle for Survival,” “The Search for Stability” and “The College in Crisis,” to name just a few.

Frequently, money — or a lack thereof — was the problem. Other times, imperious administrators and peculiar professors wreaked havoc. (See the chapters on President Paul Wagner, the “boy wonder” who was fired and refused to leave, and Professor John Rice, the iconoclast who enraged the community with his atheism and arrogance.)

In 1991, Lane and Rollins English professor Maurice “Socky” O’Sullivan compiled a collection of Florida writing ranging from folk tales and Spanish myths to Florida-related work by such writers as Ralph Waldo Emerson, John James Audubon, Zora Neale Hurston, Zane Grey, Wallace Stevens, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Jose Yglesias and Harry Crews. Visions of Paradise: From 1530 to the Present (Pineapple Press) won the Florida Historical Society’s Tebeau Award as the year’s best book on Florida history.

In addition, Lane’s stories for scholarly journals and consumer publications such as Winter Park Magazine revealed — and continue to reveal — even more previously untold stories about the community’s past. In 2005, he wrote a corporate history of Winter Park Memorial Hospital, now AdventHealth Winter Park.

During his career at Rollins, Lane was recognized with several prestigious honors, including the Arthur Vining Davis Fellowship Award in 1972, the Alexander Weddell Professor of the America’s Chair in 1978 and the William Blackman Medal in 1997. At its 2006 commencement exercises, Rollins awarded him an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree.

In recent years, Lane — who retired from the college in 1999 and granted professor emeritus status — has conducted historical tours of the campus, assisted as guest lecturer in several classes, and served on the boards of Casa Feliz and the Winter Park Institute at Rollins College.

He has also been a member of exhibition committees for the Winter Park Historical Society. He and his wife, Janne, even live in a designated historic district, College Quarter, in a home that’s listed on the Winter Park Register of Historic Places.

Says Susan Skolfield, executive director of the Winter Park History Museum: “No one has done more to connect the histories of town and gown in Winter Park than Rollins’ favorite historian. Through his writings, lectures and advocacy, Jack has not only been a beloved instructor for Rollins students, but for every Winter Park resident as well. We are delighted to honor him at this year’s Peacock Ball.”

Winter Park Magazine recently sat down with Lane for a conversation, portions of which follow.

Q: You were the first in your family to attend college. What was it like growing up, and what motivated you to become a Ph.D. and then a professor?

A: I grew up in rural Texas about 15 miles from Austin in a small town called Elgin. I was born in the depths of the Great Depression. My father was a truck driver for a local brick company and, as I remember, we lived pretty much paycheck to paycheck. We were poor but not destitute.

I was the second one in my large extended family to graduate from high school. College was completely beyond my expectations, nor was I encouraged to go.

As I look back, it seems I’ve lived my life in two separate worlds — the first an impoverished world rooted in 19th-century agrarian values, religiously and socially very conservative; the second an urban, academic world, socially and ideologically liberal. On my many return visits to my family’s world, I felt as if I had entered a foreign country.

After high school, during the Korean War era, I spent three years in the Army Airborne Division. After discharge, with the help of the G.I. Bill, I entered college (at Oglethorpe University in Atlanta).

An American history class led me to dream of being a college professor. Before that moment, such a possibility had never entered my mind. Later, with the support of my soulmate and wife, Janne, I achieved that unlikely goal. How I got to Rollins is another story.

As I look back, it seems I’ve lived my life in two separate worlds — the first an impoverished world rooted in 19th-century agrarian values, religiously and socially very conservative; the second an urban, academic world, socially and ideologically liberal.

Q: Were you always interested in history? Can you point to a specific time or incident that convinced you that you wanted to be a historian? If you hadn’t been a historian, what field might you have pursued?

A: I was an indifferent student in high school, interested more in sports than academics, but I did enjoy my history courses. As mentioned, I purposely chose an American history course as my first class in college and that set me on my career course.

I had two dreams when I graduated from high school — one was to be a musician, but with my family’s economic situation, that remained only a dream. The other was to play professional baseball.

I did play for a semi-pro team for a year while at the same time working in Austin. And in the spring of 1951, I was asked to try out for the University of Texas baseball team. But the Korean War intervened and that never happened.

The one thing that never entered my mind in those years was a career as a college professor. I didn’t even know what a Ph.D. was.

Q: What brought you to Winter Park and Rollins College?

A: That’s a long story, but here’s a brief version. After receiving a doctorate (from the University of Georgia) in the spring of 1963, I had offers from three big universities, and wasn’t particularly satisfied with any — but by May, the schools wanted an answer.

Just as I was ready to decide, the department head told me that someone had called him about an opening at a small college in Winter Park, Florida.

Where the heck was Winter Park, Florida? It was hard to find it on a map. I had never heard of Rollins or even been to Florida, but it sounded like what I wanted — a small liberal-arts college.

I called, they invited me down, I saw the college and town and fell in love with both. They offered me the position and I accepted. We’ve never left.

Q: What were Rollins and Winter Park like when you came, and how have they changed?

A: As I began to research the college’s history, I realized that I had arrived at the end of one era and the beginning of another. I was fortunate enough to experience both.

The first I would characterize as the New England patrician era. The college community was infused with a certain kind of gentility led by independently wealthy New Englanders. There was a sense of elegant leisure and gracefulness. And the town exhibited the same behavior.

There was a kind of lazy acceptance of the world as it was. I had come from the turmoil and excitement of the early civil rights movement in Atlanta and Athens, Georgia, to a place that seemed totally indifferent to what was happening in the rest of country. I experienced a kind of culture shock.

Then, suddenly, that changed. Older faculty retired, new faculty arrived and so did the war in Vietnam, the civil rights movement and the youth movement. Rollins and Winter Park finally joined the world — and everything changed.

There was a kind of lazy acceptance of the world as it was. I had come from the turmoil and excitement of the early civil rights movement in Atlanta and Athens, Georgia, to a place that seemed totally indifferent to what was happening in the rest of country. I experienced a kind of culture shock.

Q: What do you think is the single most important event in the history of Rollins, and why? How about for Winter Park?

A: Well, that’s a hard question to answer. There are so many turning points in both their histories.

The Hamilton Holt era (Holt was president of the college from 1925-49) clearly was a transformative time in the college’s history, when it began to shift — in its mission, in its academics and even in its architecture — from a New England-based college to a Florida-based college.

Still, for a while it retained a New England patrician culture. As I later realized, the McKean presidency (Hugh McKean was president of the college from 1951-69) was essentially an extension of the Holt era. In the 1960s and 1970s, that patrician culture encountered the modern world and it began to crumble.

Then, between 1969 and 2004, two dynamic presidents — Thaddeus Seymour and Rita Bornstein — took the college to a whole new level, where it remains today.

Winter Park went through a similar transformation. It went from a small, intimate service town to one dominated by businesses catering to tourists. The only evidence of that former town today is Miller’s Hardware. Miller’s remains an icon of days long past.

In Winter Park, we’ve lived through two eras that I call BD (Before Disney) and AD (After Disney). Enough said. Well, perhaps one more comment — I’m personally not nostalgic about some aspects of the little village I found in 1963, where they wouldn’t allow children to live in the apartments we wanted to rent.

Whatever the town’s charm — and it was very charming — I would not prefer to live in a world of old wealth somnolence.

I’m personally not nostalgic about some aspects of the little village I found in 1963, where they wouldn’t allow children to live in the apartments we wanted to rent. Whatever the town’s charm — and it was very charming — I would not prefer to live in a world of old wealth somnolence.

Q: Who would you rank as the top five most important figures in Rollins’ history, and briefly why?

A: Well, at the top of the list would be the obvious one, Hamilton Holt. He’s such an iconic figure — not only at Rollins but in the larger community — that it’s difficult to come up with new accolades to express his impact.

Under Holt’s leadership, Rollins was transformed, both educationally and physically. He established its identity as a proponent of innovative, experimental teaching and learning. His leadership made it a nationally recognized institution of higher education.

Moreover, he transformed the campus with more than 30 buildings constructed in the Mediterranean Revival architectural style. That’s one reason that Rollins is routinely recognized as having the nation’s most beautiful campus.

Then there are two presidents at the turn of the century who would make my list. One was the almost-regal George Morgan Ward (president from 1896–1902, and acting president on two subsequent occasions), who gave the college stability and daringly abandoned the classical curriculum.

Then there was William Freemont Blackman (president from 1903–1915), who brought the college back to its liberal education roots when it was drifting toward vocational or professional education. By the way, seven decades later, President Seymour did the same thing.

Also, I’d include the Blackman family, including President Blackman’s wife, Lucy, and their three children. They were by far away the most delightful and entertaining presidential family. The chapter on Blackman in my centennial history book was fun to write. Prophetically, I was presented the Blackman Medal at my retirement.

Still, I think the unsung heroes have been the generations of trustees, faculty and students — particularly those who stuck with the college in times of serious adversity. They never lost the faith when many wanted to throw in the towel. I spend some time revealing their tireless efforts.

Q: You were originally interested in military history, but much of your scholarship is on the history of Rollins. In fact, the only authoritative history of Rollins is your book. Did you feel a sense of mission to document the history of the institution?

A: Well, to answer that question is to reveal one of my character flaws — but I’ll answer anyway. I have a very short attention span when it comes to scholarship.

I drifted in my scholarly publications from military history to the history of American foreign policy to the history of education to Florida history and finally to the history of Rollins. As you can see, with age my perspectives got narrower and narrower.

And yes, I felt the college had given me so much that I owed it something in return, and the “authoritative history” as you call it was my contribution.

But more than that, I realized that the college was losing its institutional memory, and that was very dangerous — and it’s even more dangerous today. Because the college is in this COVID-19 era, it should be reminded that the subtitle of my history is “A Story of Perseverance.”

This current threat is by no means the first test of resilience the college has faced. Some tests, in fact, have been far more serious. Yet, it’s still here and thriving.

Q: The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly challenged Rollins and all colleges. But you say the institution has overcome more serious threats. What were they?

A: I chose the theme of “perseverance” because there were so many periods when it seemed the college wouldn’t survive. But the struggles gave it strength to weather storms of adversity at times when countless other colleges facing similar problems went under.

But to answer your question about a specific period: I would say the immediate years after World War I. The conflict had almost denuded the college of its male students and depleted its finances. It emerged from the war deeply in debt.

Many wanted to give up the struggle as a lost cause. That’s when Hamilton Holt came to the rescue — the college’s knight in shining armor, if you will.

Q: What facet of the college’s history surprised you the most?

A: Well, there was very little that I did know of Rollins’ past, so I found many surprises. Part of my reluctance at first to undertake writing the book was the idea of doing an institutional history — that it would be dull.

But was I wrong. Not only was it not dull, but as I began to dig into the material in the archives, I quickly found the story fascinating. What human drama here!

A group of intrepid Congregationalists (Rollins was founded by the Florida Congregational Association and members of the First Congregational Church of Winter Park) had either the audacity or the foolhardiness to start a college in the Florida wilderness, in a village that had only about 150 souls.

What’s more, they installed a course of study that required extensive preparation in classical languages and literature. For heaven’s sake, there weren’t even any secondary schools in Florida at that time.

How the college survived — through epidemics, freezes, internal conflicts and exhausted finances — was a story that captivated my interest from the very beginning. It involved heroic effort on the part of many individuals.

And then I found that the college’s history was populated by engaging and brilliant personalities — some of whom did the college no favors, and others of whom were instrumental in pulling the institution through its adversities.

Q: Did writing the book give you a greater appreciation for Rollins? In what way?

A: Oh my, yes. For so many reasons. Because I knew so little of the college’s past, I had countless “ah ha” moments during my research. I realized that many of the things we were doing academically had been passed down to us from previous generations of leaders.

For example, from my earliest days at Rollins, I sensed that I was expected to be innovative in my teaching, to experiment with new ideas and to create innovative educational programs. These were time-honored Rollins traditions — but I didn’t know that at the time.

Also, I was surprised to learn how long Rollins had been so renowned. It had, all along, attracted brilliant professors and highly regarded figures.

I made two major discoveries in this realm. First, I learned that Zora Neale Hurston was deeply connected to the college, and that two Rollins professors had jump-started her fabulous career.

Second, I learned that Rollins was the seedbed for the founding of Black Mountain College, probably the nation’s most celebrated experimental institution. Former Rollins professors started the school in North Carolina.

Let me just add here what I see as an important insight that came to me as I researched the college’s past. As I mentioned earlier, the college community was in danger of losing its institutional memory. I had that fact reinforced to me time and time again.

As I had been reminding my history students, ignorance of our past can be seriously damaging. For a college, that can mean dangerously wandering into ways that seriously impair its historic mission.

Forgive me if I include a quote from President Cornwall’s forward to the book: “In this time of rapidly shifting changes, one that requires (re)envisioning the role of liberal education in a global context, it is critical that present and future Rollins generations embrace the distinctive character that previous generations strove to build.”

My hope was that Rollins College Centennial History provided assurance that we will never forget this college’s past — and particularly how previous generations doggedly kept alive the commitment to liberal education. That’s one of the meanings of the motto, “Fiat Lux.”

As I had been reminding my history students, ignorance of our past can be seriously damaging. For a college, that can mean dangerously wandering into ways that seriously impair its historic mission.

Q: What accomplishments, personally and professionally, are you most proud of?

A: My first published book was the most exciting thing that happened to me professionally. Did you realize that only about 1 percent of professors ever get a book published?

But then — and this one may surprise you — I consider my most enduring accomplishment academically has been to create the Summer Teaching/Learning Workshop for the Associated Colleges of the South (ACS).

The ACS, of which Rollins is a proud member, is composed of the best liberal-arts colleges in the South. I created and guided a group of facilitators and participants through several summer workshops until it was well established.

This year will be the 30th year the ACS will offer the Summer Workshop, now headquartered at Sewanee College (near Chattanooga, Tennessee). Professionally, nothing has given me more satisfaction than to see one of my creations help so many young faculty.

Q: What’s one thing most people would be surprised to learn about you? You mentioned earlier wanting to have been a musician, for example.

A: Well, let’s see — for those who don’t know much about my background, they’d probably be surprised to know that during my early 20s I sang the third part and played drums and vibes with a professional jazz vocal quartet called The Tradewinds.

We made several recordings, of which I have one. If I may be a bit indecorous (or am I already guilty of that?) I will say that we were very good, and with a little more time may have gone to the top.

But a key member was married and had to leave the road. On the other hand, I wouldn’t have met Janne, wouldn’t have had this beautiful family and wouldn’t have had a career as professor of American history at a wonderful college in a great town.

As they say, a lot of life depends on luck and I’ve been very lucky.

THE 2020 PEACOCK BALL

Join the community for the Winter Park History Museum’s 2020 Peacock Ball, honoring Rollins College Professor of History Emeritus Jack C. Lane.

WHEN: Saturday, November 14

WHERE: The Rice Family Pavilion at Rollins College

TIME: TBA

TO ATTEND: For information about tickets and sponsorships, call the history museum at 407.647.2330 or email museum@wphistory.org.

PAST PEACOCK BALL HONOREES

2019

Joy Wallace Dickinson

“Florida Flashbacks” Columnist, the Orlando Sentinel

2018

Randy Noles

Editor and Publisher, Winter Park Magazine

2017

Rita Bornstein

President Emerita, Rollins College

2016

Saluting Life in Winter Park During World War II

2015

Debbie Komanski

Executive Director, Polasek Museum & Sculpture Gardens

2014

James Gamble Rogers II and John “Jack” H. Rogers

Architects

2013

Alfond Inn Opening

2012

125th Anniversary of Winter Park

2011

Winter Park Community Center Opening

2010

Hugh and Jeannette McKean

Founders, the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art

2009

Kenneth Murrah and Harold Ward

Attorneys and Civic Leaders

2008

Rose Bynum, Eleanor Fisher, Eula Jenkins and Peggy Strong

West Side Community Leaders

2007

Thaddeus and Polly Seymour

President and First Lady, Rollins College (1978–90)