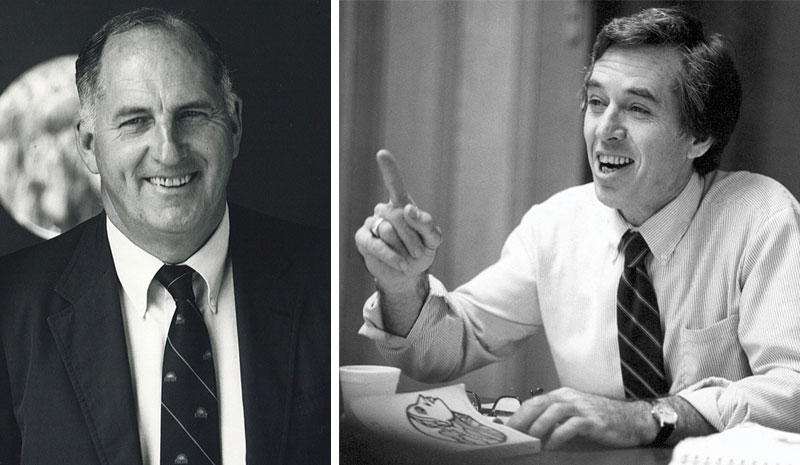

If you asked Central Casting for help in casting a fire-and-brimstone fundamentalist preacher for your next feature film, you’d probably end up auditioning a bevy of actors with characteristics mirroring those of Maitland’s Rev. John Butler Book, a jowly, dapper, silver-haired crusader whose scathing — but highly quotable — scriptural scoldings have enlivened Central Florida’s culture wars for decades.

You’d no doubt want to hire Book himself — except he isn’t an actor. Or at least he doesn’t carry an Actor’s Equity card despite his obvious talent — particularly during his pulpit-pounding prime — for performing in front of cameras.

“When Adam and Eve were naked, God realized they were sinning and put clothes on them,” intones Book, 82, as he sits by the crackling fireplace in the parlor of his Maitland home, built in 1876 and furnished with eclectic museum pieces. “That’s why when Rollins College performed Equus, we renamed the Annie Russell Theatre the Fannie Hustle Theater.”

Book helped rally community opposition to the college’s 1979 staging of the 1973 drama by Peter Shaffer, which tells the story of Martin Dysart, a psychiatrist who attempts to treat a young man who has a pathological religious (and sexual) fascination with horses.

Equus, which won two Tony Awards in 1975 (Best Play and Best Direction), includes a five-minute nude scene between the young man, Alan Strang, and a young woman, Jill Mason. The two, who are together in a stable, fail at consummating a tryst when Alan is shaken by noise from the animals — whom he later blinds using a spike.

In the 40-plus years since the Equus controversy, Book has neither mellowed nor harbored second thoughts. “I don’t regret my stand on it,” he says. “You know, liberal detergent has two ingredients — an ounce of truth and a gallon of brainwashing. Just because someone thinks something is right doesn’t make it’s right.”

Book only doubled down on his moral crusades in the ensuing years. But for producing director Jeff Storer and student actors David Lee McClure (Alan) and Darla Briganti (Jill), the brouhaha shaped their worldviews and taught them that freedom of expression becomes even more precious when you must fight for it. All three faced the threat of arrest until just hours before the curtain was set to rise on opening night.

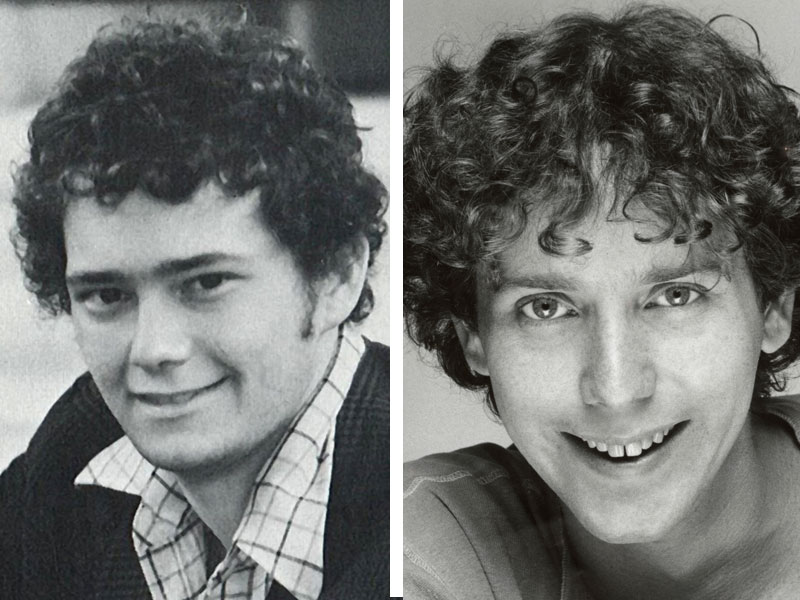

“For me, Equus was a transcendent experience,” says McClure, who after a two-decade acting career turned his professional attention to the promotion of spirits and became a “senior master of whiskey” for Empire Merchants, a leading wine and liquor distributor in Metro New York. “At first, I felt like just a teenager being quashed by the man. But Equus made me understand that a play could be important and that you could prevail. It was a huge influence on my life.”

Briganti, who continued to perform and later opened an acting school in the Florida Panhandle, agrees: “The whole thing brought the campus together, and I felt such a sense of support and community. It freed me as a person and gave me confidence in who I was.”

Storer, who went on to a distinguished career as a director and for 31 years operated an edgy community theater in Durham, North Carolina, still finds himself becoming emotional when discussing Equus: “I had never been in a position where I had to stand up for art that I believed in. But making that choice changed my life.”

OH, BY THE WAY …

Fervor for artistic expression notwithstanding, Equus wouldn’t have gone on without the support of Rollins President Thaddeus Seymour, who had been on the job less than a year when the controversy erupted. Even so, it almost opened in a significantly altered form after Seymour initially sought to pacify protestors.

Robert Juergens, director of the college’s department of theater arts, had given Seymour a head’s up that Equus had been slated for “the Annie’s” 1979 season. Seymour assured Juergens that he supported the decision to present the play, which had been a critical success on Broadway.

It had also been a critical success in Orlando. A touring production by Gainesville’s Hippodrome Theatre had run for seven performances the previous year — without incident — at Orlando’s Great Southern Music Hall.

“I said, ‘Bob, one thing I would urge is that you be sure your ticketholders understand [that the play includes on-stage nudity], so that nobody gets blindsided and grandmothers, or whatever, aren’t embarrassed,’” recalled Seymour in a 2005 oral history interview.

He added: “And be sure the actors have been in touch with their families, so you don’t have some mother say, ‘You know, this old goat of a director made my daughter take her clothes off in front of that audience.’”

Seymour, though, was surely trepidatious. He valued town-gown relations, and later admitted that Equus was “an issue I didn’t need” so early in his presidency — just as the community was sizing him up.

He also prized collegiality, and recalled that his time as dean of students at Dartmouth College had been marred only by student demonstrations — one of which involved his preplanned ejection from the administration building by protestors. Rollins, he had assumed, would be a much less turbulent place.

Further, the director of Equus wasn’t going to be an old goat — it was going to be Storer, a 26-year-old Rollins graduate who was an assistant professor of theater and, by his own admission, more than a little naïve about the tolerance of some Winter Parkers for edgy theatrical experiences that involved nude teenagers.

Says Storer: “We thought, ‘Wow! Isn’t this great? Winter Park can do this sophisticated work and have no complaints.’” He held auditions for the roles of Alan and Jill behind the curtain on the Annie Russell stage and made certain that parents were on board before any garments were shed.

McClure, a sophomore and son of a senior associate minister at the First Presbyterian Church of Winter Park, had the backing of his parents. “My dad was a liberal and fought with churches,” says McClure. “He thought it was great not because of the nudity but because of the art.”

Briganti, an Altamonte Springs freshman whose parents were more dubious, nonetheless supported their live-at-home daughter’s aspirations and likewise did not object. Perhaps not surprisingly, she recalls, more students auditioned for the role of Alan than for the role of Jill — which attracted the interest of only three young actresses.

“I suppose a female willing to [appear nude] could gain something of a reputation among male students,” Briganti says. “But I was a serious artist. It was all handled so professionally that I never felt uncomfortable at Rollins.”

POLICING EXPRESSION

Rehearsals, with McClure and Briganti clothed for the controversial scene, began. “We all worked our butts off,” says Storer, who was relieved when only four letters of protest resulted from a preemptory mailing to the theater’s 1,700 season subscribers. Then, however, everyone else got wind of seemingly unsavory goings-on at the Annie.

On April 18, the Orlando Sentinel ran a story headlined “Nude Scene in Rollins Play Stirs Only Mild Protest.” Seymour told reporter Jody Feltus — in retrospect, rather defensively — that the decision to schedule Equus was made prior to his hiring. “I feel it is my obligation to defend their decision,” he added, because the college “is an intellectually free environment.”

Storer added: “I have faith in the maturity of our audience. I have to. There will always be those who object to nudity — period. They will drape a towel around a nude statue. I can’t change their minds.”

Public nudity? And protests were only “mild?” Sentinel readers, most of whom had never attended a play at the Annie and none of whom would be compelled to attend Equus, were horrified. Still, only 18 people — some of them, perhaps, members of Book’s congregation at the Northside Church of Christ — lodged informal complaints at City Hall.

Response remained muted, but it was enough to prompt officials to act. On May 1, a letter written by Frederic B. O’Neal, assistant city attorney, was delivered to a shaken Storer on campus by an armed, uniformed police officer. “I couldn’t believe it,” says Storer. “I had never been arrested for anything in my life.”

Winter Park had an ordinance, the letter explained, that made it “unlawful for any person within the corporate limits of the city to be found in a state of nudity.” (The language of the ordinance, which is still on the books, appears to make no exception for bathing.)

Further, the letter stated, it was unlawful to solicit nudity — and Storer, as director, could be charged with that offense. O’Neal added that in his opinion the nude scene “could be presented with the use of feigned rather than actual nudity, thereby allowing the play to be presented without risking a violation of the law by anyone.”

The play was scheduled to open on May 3, and authorities had threatened to arrest two students and the director if it was performed as written. City commissioners, however, were divided on the issue. Byron Villwok said he accepted nudity in paintings, but not in films and performances because people “jump around and are in motion.”

Jerome Donnelly found the situation absurd and opined that police should concentrate on “real issues” such as robberies. Harold Roberts agreed, calling the controversy “much ado about nothing … no one is forced to go down there.”

The decision to threaten arrest appears to have been advocated by City Attorney Richard Trismen, who the previous week had met with Police Chief Ray Beary, City Manager David Harden and Assistant State Attorney Lawson Lamar to discuss how to respond. “It will be up to the city attorney if the play will be closed down or not,” Beary told the Sentinel.

On campus, Seymour struggled to find a compromise. “I am appalled by the harassment of the young actors and the director by members of the community,” he said. The perennially genial president also deplored the way in which some city officials equated a serious dramatic production with a topless bar.

Although it wasn’t reported at the time, the potential felons — and in Briganti’s case, her family — had all received threatening or obscene anonymous calls. “People called up my parents to tell them what a slut I was,” recalls Briganti. “They didn’t deserve that kind of treatment.”

Still, a reluctant Seymour instructed Storer to find a way to cover the actors. Juergens, though, was appalled, telling the Sentinel that “this action says much about the city’s attitude toward artistic freedom. It is lamentable.” In the meantime, outrage was growing among students and members of the faculty.

Storer, in a grudging attempt to comply with the city’s mandate, whisked his actors away on a frenetic shopping excursion to Park Avenue to buy appropriate flesh-colored clothing — perhaps lingerie for Briganti and a bathing suit for McClure. Briganti says that being scantily clad made the scene seem, for the first time to her, like pornography.

The first-year director had already begun composing a speech to be delivered following curtain call pointing out that the play had been censored. “Clothing the scene is akin to putting a top hat on a horse,” he would have said — had the speech been necessary.

Storer also wrote a press statement that was never released. It read, in part: “Winter Park has long held itself as a citadel of artistic expression. The question remains: At what point does legal censorship govern the artistic merits of a work? We as educators try to create an environment in which students are allowed artistic and intellectual freedom. It is this freedom we feel has been compromised.”

Briganti kept a low profile, but McClure was more vocal, telling the Sentinel that he would be willing to risk arrest by disrobing. “I remember going down in the basement of the theater and just screaming, the way only a teenager can,” he says.

AMUSEMENT TO OUTRAGE

On May 2 — with the curtain set to rise in fewer than 24 hours — Arnold Wettstein, a professor of religion and dean of the Knowles Memorial Chapel, addressed about 300 students and faculty members at a “town meeting” held in the campus’s Bush Auditorium. Wettstein told the overflow crowd that his feelings had evolved “from amusement to anger to outrage to humiliation.”

An occasional performer in productions at the Annie, Wettstein compared tampering with Equus to the vandalism several years earlier of the Pieta in the Sistine Chapel. “If you work in the theater, you know what it is to devote time and interest to transfer a dead script into something of meaning, value and significance then to see it smashed into fragments,” he said.

Seymour, who was warmly received at the meeting, began his remarks by seeking to justify clothing the actors as a despicable but necessity measure to protect Storer, McClure and Briganti. “When someone looks me in the eye, I want to be able to say that Rollins obeyed the law,” he added. “I’ve spent too much of my life protecting orderly change.” Seymour noted, however, that no one could prevent speeches from the stage following each performance.

However, the college community was in no mood to settle for speeches. Other faculty members rose to decry the anti-nudity ordinance and its application to Equus, and urged Seymour to challenge the city and guarantee legal representation to anyone arrested. Finally, a student suggested that the college seek legal advice on the possibility of getting a judge to issue a restraining order against the city.

Seymour, himself a performer who presented magic shows, was adept at reading a room. His response, answered with a thunderous ovation, was, “I will proceed accordingly.”

Hundreds of students then marched from the college to City Hall, where they presented Harden with a petition that asked officials to reconsider their interpretation of Equus as a violation of the city’s anti-nudity ordinance and allow the play to continue without interference from police.

The protestors also draped a bra and panties over the statue of a nude woman fronting City Hall. The replica of Forest Idyl, by famed sculptor Albin Polasek, had stood on municipal property since 1965. Presumably Villwok hadn’t advocated for the work’s removal because it didn’t “jump around.”

Still, Seymour had a problem: The city attorney and the college attorney — Richard Trismen — were one in the same. So Seymour asked legendary local lawyer Kenneth Murrah, who had volunteered to help the college, about going to court and seeking a restraining order. Murrah got right to work.

On May 4, just hours before the curtain was set to rise, U.S. District Judge John A. Reed presided over a hastily called hearing in a downtown Orlando courtroom. Ironically, Reed had two tickets for Equus and wondered aloud if this conflict of interest should prevent him from ruling at all.

Attorney Lee Sasser, an associate of Murrah’s, said: “Your Honor, Dr. Seymour, president of Rollins, is in the courtroom, and I know if you requested it, he would fully refund your tickets for tonight.” Replied Reed: “OK. But you’ll have to explain this to my wife.”

The judge issued a temporary restraining order that allowed the show to go on without immediate legal consequences for the participants — but he did not, as the college had hoped, rule that the ordinance was unconstitutional. Theoretically, arrests could be made later, when the order expired.

Ultimately, however, the city and the college agreed that state law — which made exceptions for educational activities and had already been ruled constitutional — would take precedence over the local ordinance where artistic expression was concerned. The college’s suit against the city was dropped in August.

On opening night, Seymour noted a handful of picketers on campus led by the ubiquitous John Butler Book. “I remember one of the signs distinctly,” said Seymour, who always laughed when he repeated the story. “It read, ‘Seymour Wants to See More!’”

If Book’s campaign had any effect, it was to sell more tickets. Houses were packed and reviews were generally good, although the Sentinel’s headline read, “Rollins’ ‘Equus’ Competent, But Lacks Excitement.”

Writer Sumner Rand found Storer’s direction “too literal,” but opined that “the nude scene is not downplayed, nor is it sensationalized. It flows naturally in the context of a psychiatric examination and, symbolically at least, demonstrates the vulnerability of Alan.” McClure, added Rand, “gives a bravura performance.”

Charley Reese, the newspaper’s arch-conservative columnist, accused the college of grandstanding by calling attention to the nude scene and bellowed that “artistic integrity and academic freedom, for that matter, should not be construed as licenses to do whatever one damn well pleases.”

SECOND ACTS

Following Equus, McClure was pleased to find that his campus coolness quotient had increased exponentially. “I went from being a history major who worked in the scene shop to being a celebrity in this little town,” he says. “I was at the center of this incendiary issue that everybody was interested in. It was crazy.”

McClure changed his major to theater and revelled in being called “Spike,” a nickname based on the instrument his Equus character used to maim horses. “Spike” McClure is the name he has gone by ever since.

After graduating from Rollins in 1981, McClure earned an MFA in acting from Ohio State University and moved to Manhattan, where he appeared in productions at the Public Theater and on Broadway at the Circle in the Square Theater. He even returned to Rollins in 1988 to play the lead in Tom Stoppard’s comic-drama The Real Thing.

During several Los Angeles sojourns, McClure landed some film roles. But after marrying and having a child in 1998, he gave up acting and joined the wine and spirits industry. “I couldn’t believe you could actually get a job doing what I do,” says McClure.

Briganti left Rollins after her sophomore year because she had been offered a full scholarship to the University of Florida, where she graduated in 1982 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in acting. She spent the next 30-plus years as an actor, singer, dancer, director, choreographer and acting coach. In 2010, she opened an acting school for children and adults in Destin.

Briganti says she was at first “angry that the media sensationalized the situation” surrounding Equus. But her anger was replaced by empowerment, thanks to the collective support of the campus and the excitement of standing up for artistic freedom. “I thought, ‘Wow! This is what the ’60s must have been like,” she says.

McClure and Briganti both praise Storer for his unflagging professionalism and Seymour — a relatively new president — for his courage in standing up with them despite what appeared to be significant community opposition.

Storer left Rollins the following year (1981) and enrolled in Trinity University’s MFA program, which is housed at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Dallas Theater Center. He, too, went on to enjoy a long career as an actor, director, playwright, producer and professor in the department of theater studies at Duke University.

In 1987, Storer and his partner — later husband — Ed Hunt, founded Manbitesdog Theater in Durham, North Carolina, where they staged often-controversial contemporary plays until they decided to close the venue in 2018.

“It was a tremendously emotional time,” says Storer of his Equus days. “I had to keep it together. But the experience shaped the rest of my life. I believe that we as a society have to support art that we value, or it will go away.”

Equus may have had a huge impact on Storer, McClure and Briganti, but it was just one of many social scourges battled by Book, who in 1991 was arrested and charged with disrupting a freedom of expression forum held at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum.

Details are murky, but apparently Book brought a video camera to the meeting, where photography was prohibited because the artwork on display was copyrighted. Heated words were exchanged, and Book was taken into custody when police were called. Prosecutors dropped the charges a month later, and Book sued the City of Winter Park. (The case was ultimately settled.)

In 1993, Book became the only pastor in the state’s history to have his opening prayer expunged from the records of the Florida Senate. The six-minute oration — delivered as even the most conservative lawmakers squirmed — decried homosexuality, necrophilia, liberals in general and even public schools, where he lamented that “reading, writing and arithmetic have been replaced by romance, reproduction and revolution.”

Sunday liquor sales, the Equal Rights Amendment, Mel Gibson’s film The Last Temptation of Christ and scandal-ridden televangelists such as Jim and Tammy Bakker have been targets of Book’s wrath. In person, though, he’s surprisingly chatty and likeable even as he spouts opinions that range from absurd to offensive.

As far as Equus is concerned, Book says that at least the college learned its lesson and never tried anything as outrageous again. When told that Equus was, in fact, staged for a second time at Rollins in 2007, he expressed genuine surprise: “Really? Well, I didn’t know about it. If I had, I’d have sure been there.”