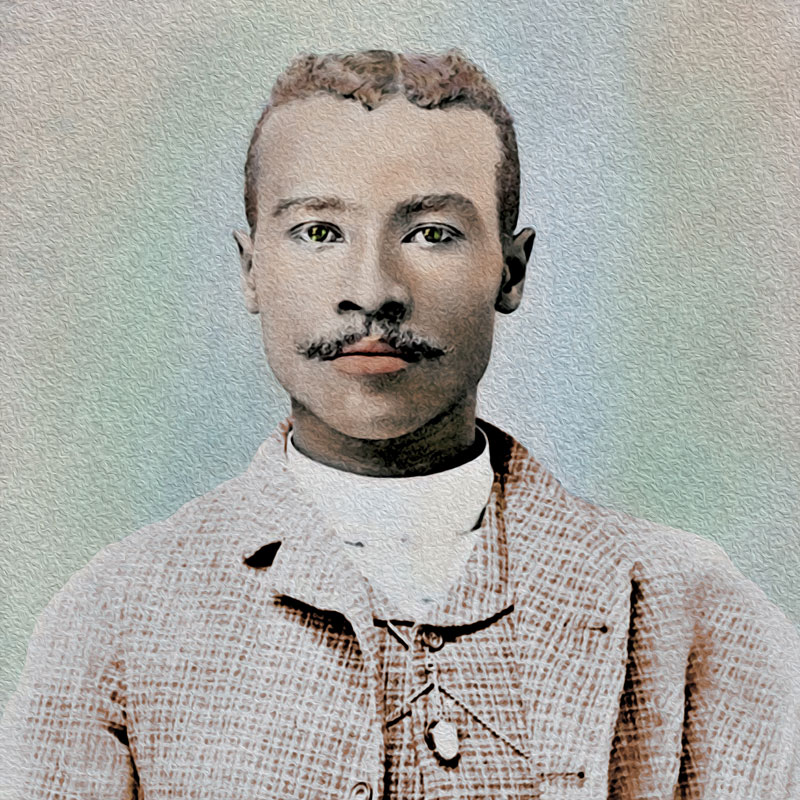

Valencia College has had a campus on the west side of Winter Park since 1996. But it’s reaching back more than a century to recognize one of the Hannibal Square neighborhood’s most important historical figures — newspaper editor and activist Gustavus C. “Gus” Henderson.

Last year, the college presented its first Gus Henderson Scholarships to a pair of deserving locals. In addition to demonstrating a financial need, recipients of the $1,000 awards must be graduates of Winter Park High School and enrolled at Valencia College’s Winter Park Campus. Going forward, older students who wish to return to college will also be eligible.

Fairolyn Livingston, chief historian at the Hannibal Square Heritage Center — which preserves and celebrates the history of the traditionally African-American west side — suggested that the scholarship program be named for Henderson, whose efforts were instrumental in the incorporation of Winter Park in 1887.

“Gus was successful because he valued the written word and education,” says Livingston, who notes that Henderson published the first newspaper in Winter Park, the Winter Park Advocate. (Lochmeade, a newspaper that preceded Henderson’s, was headquartered in Maitland.)

In fact, Valencia had previously set aside scholarships for residents of the west side — but the program had somehow fallen through the cracks. Newspaper clippings from the late 1990s indicate that the college had once offered as many as a half-dozen such awards annually until the program ceased.

One impetus for the original scholarship program was community relations. When the college bought its facility at 850 West Morse Boulevard in 1996, the property was rezoned from residential and office to public/quasi-public.

Many west side residents objected because of traffic concerns, and the Winter Park Planning and Zoning Board recommended against the rezoning due to opposition from the neighborhood. City commissioners, however, voted to grant the zoning change.

At the time, the college agreed to offer scholarships for west side residents — and followed through for several years. But no agreement was put in writing, and the program vanished as college administrations changed and memories faded.

Livingston and other community leaders hadn’t forgotten, though. For years they had been directing potential students to Valencia with instructions to inquire about the scholarships. But at the college there was no record of the program’s existence and no dedicated funding source. The usual response was, “Gus who?”

The program’s demise usually wasn’t an insurmountable issue, says Sue Foreman, past chairperson of the Valencia College Foundation, a nonprofit organization that raises scholarship funds from private sources. “Other scholarships were available, so the students were assisted. But no one knew about this earlier program.”

So in 2018, Foreman convened a committee consisting of Livingston; Mary Daniels, a docent at the Hannibal Square Heritage Center; Lee Rambeau Kemp, a community activist; and Elisa Mora, a guidance counselor at Winter Park High School.

Other members included Ronnie Moore, assistant director of the city’s parks and recreation department; Elizabeth “Betsy” Swart, an adjunct professor of sociology at the University of Central Florida; and Anne Thomas, mentor coordinator at Winter Park High School.

The group, called the Gus Henderson Committee, decided to formally revive the scholarship program and to adopt Livingston’s suggestion to name the effort for Henderson, whose importance to the city’s history is not generally well known — but should be.

“It’s wonderful to be able to tell this story through the scholarship program,” says Foreman. “Especially because we’re able to spotlight a person whose name should be remembered.”

WHY GUS MATTERED

Henderson was a newspaper publisher, an entrepreneur and a civic activist who rallied his neighbors and was instrumental in making certain that a contentious referendum to incorporate Winter Park passed in 1887.

Like many African Americans during the 1880s, Henderson and his family moved here because Winter Park was thought to be a relatively enlightened place where they could own their own homes — albeit only on the west side’s designated “colored lots” — and control their own destinies.

The politically savvy Henderson, who had been a traveling salesman, started a print shop and later established the Advocate, a weekly newspaper that primarily covered activities in the Hannibal Square neighborhood but was equally well-read east of the railroad tracks.

Henderson, working alongside city founders Loring Chase and Oliver Chapman, was instrumental in turning out voters from Hannibal Square, which resulted in the incorporation of Winter Park and the election of two African-American commissioners in 1887.

“If it were not for Henderson’s efforts, the incorporation of Winter Park would not have taken place on October 12, 1887, and Hannibal Square may not have originally been included within the town limits of Winter Park,” Livingston says.

The victory, however, would be relatively short lived. Henderson was an ardent Republican, as were most African Americans at the time. So, when Winter Park was incorporated with boundaries encompassing Hannibal Square, the political balance of power shifted.

William C. Comstock, a grain merchant from Chicago, led an effort in 1893 by Democrats to de-annex the close-knit neighborhood. Although Winter Park’s elected officials refused to change the boundaries, the Florida Legislature did so over their opposition.

In the pages of the Advocate, an anonymous editorial writer — probably Henderson — wondered how Comstock and his associates “could sign their names to such an undermining petition, and one showing such bitterness toward the colored population of this town … there never was a more bitter spirit in existence against the colored people than what is hid behind this scheme.”

Hannibal Square was not a part of incorporated Winter Park again until 1925, when local leaders sought a change in status from town (fewer than 300 registered voters) to city (300 or more registered voters). Henderson moved to Orlando in 1906 and died there in 1915. His legacy, however, lives on through the west side’s continuing pride and activism.

BRIDGING THE DIVIDE

Winter Park is thought to be an affluent place — and it generally is. But areas of scarcity still exist, and there are substantial numbers of working poor who find Valencia’s modest $103 per credit hour tuition beyond their reach without assistance. It surprises many to learn that 40 percent of Winter Park High School students qualify for free or reduced lunch prices.

So, the Gus Henderson Scholarship serves a dual purpose: It honors a community leader and provides a lifeline for young people seeking higher education.

The first set of scholarships were made possible by a donation from St. Margaret Mary Catholic Church’s Bridging the Color Divide Program. The program began in 2018 with a daylong conference related to an Advent service and grew into a communitywide effort to bring about compassion and understanding.

“In Winter Park, the railroad tracks have historically been a color divide between black and white neighborhoods, historically forming a barrier across which black residents had to retreat by sundown,” says Swart, who in addition to teaching serves as the group’s parish coordinator.

Bridging the Color Divide, Swart notes, “works to replace that barrier with bridges of justice and community” between the west side and the east side.

Today, the group boasts participants from a diverse assortment of local churches from both sides of the tracks as well as the Hannibal Square Heritage Center.

The first two recipients, Valencia students Tonya Carlisle-Francis and Aaliyah Medina, say they plan to pay it forward once they complete their educations.

Carlisle-Francis, whose goal is to earn a bachelor’s degree in business administration, hopes eventually to open a center to care for seniors and children. “I want to help my community here in Winter Park and give back the support that was given to me,” she says.

Medina says she’d like to someday become a child psychologist, hopefully at Nemours Children’s Hospital. “It’s because of assistance like the Gus Henderson Scholarship that I can try and change the world, one child, at a time,” she adds.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

To donate to the Gus Henderson Scholarship, visit the Valencia College Foundation’s website at valencia.org/gushenderson. You can mail a contribution to: Gus Henderson Scholarship, Valencia College Foundation, 1768 Park Center Drive, Orlando, Florida, 32835.

In addition to a roster of individual donors — including Henderson’s oldest living grandson — governmental agencies and foundations are stepping up. Among them are the Winter Park Community Redevelopment Agency and The Joe & Sarah Galloway Foundation, both of which have contributed grants to bolster the fund.

All contributions are tax deductible, and 100 percent of every dollar donated goes directly to the scholarship. More money raised means more scholarships can be awarded later this year and beyond.

Adds Terri Daniels, executive dean of Valencia’s Winter Park Campus: “The Gus Henderson Scholarship will honor [Henderson’s] memory of community service by ensuring that our residents have the resources needed to pursue academic goals that will have a long-term, positive impact.”