For years, a friend and I have enjoyed late-evening walks through the older Orlando neighborhoods near our home, grumbling now and then when we pass yet another modern two-story being built over the tear-down ruins of yet another favorite old-Florida bungalow.

Hope there’s at least one we don’t have to worry about.

It’s in College Park, two blocks west of Edgewater Drive at the corner of Shady Lane and Clouser Avenue, protected on one side by a 250-year-old live oak with the stoic majesty of a palace guard and on the other by a green, gold-lettered historic marker that reads, in part:

JACK KEROUAC HOUSE

Writer Jack Kerouac (1922–1969) lived and wrote in this ’20s tin-roofed house between 1957 and 1958. It was here that Kerouac received instant fame for publication of his bestselling book, On the Road, which brought him acclaim and controversy as the voice of the Beat Generation.

If you’re looking for a literary shrine with gravitas, curb appeal, a fancy gift shop and tours every hour on the hour, you’ll have to look elsewhere. Orlando’s only famous-author milepost is an unpretentious affair, with sturdy hardwood floors and an old-fashioned, howdy-neighbor front porch.

The house might have disappeared altogether had it not been for Bob Kealing, who was a WESH-TV journalist in the mid-1990s when he discovered its beat-generation heritage and wrote a magazine article and book about its former resident.

Those efforts inspired The Kerouac Project, a grassroots effort among historic preservationists who purchased the residence and transformed it into a social hub for local bibliophiles and a revolving residence for authors — four of whom are selected from roughly 300 applicants from the U.S. and around the world to spend three months here focusing on works of their own.

“There’s something empowering in this house. You can feel it,” says Austin, Texas, author Chelsey Clammer, who worked on several autobiographical essays — and saw one of them published — during her recent residency.

Kerouac was still unknown when he came to Orlando from New York City after finally finding a publisher for On the Road, his autobiographical road-trip novel that described a 1940s freight-train-jumping expedition punctuated by jazz, poetry, sex, drug use and spiritual ruminations.

The bungalow was sectioned off into two units at the time, and the adventuresome yet chronically shy Kerouac holed up in a narrow, $35-a-month apartment in the back with a roommate: his mother. Kealing still marvels at the irony of it: “Here was this hitchhiking avatar of personal discovery, living in the suburbs of Orlando with his mom.”

While On the Road was on the road to becoming both celebrated and vilified as a counterculture manifesto, Kerouac lived in relative anonymity while cranking out stream-of-consciousness prose for a sequel, The Dharma Bums.

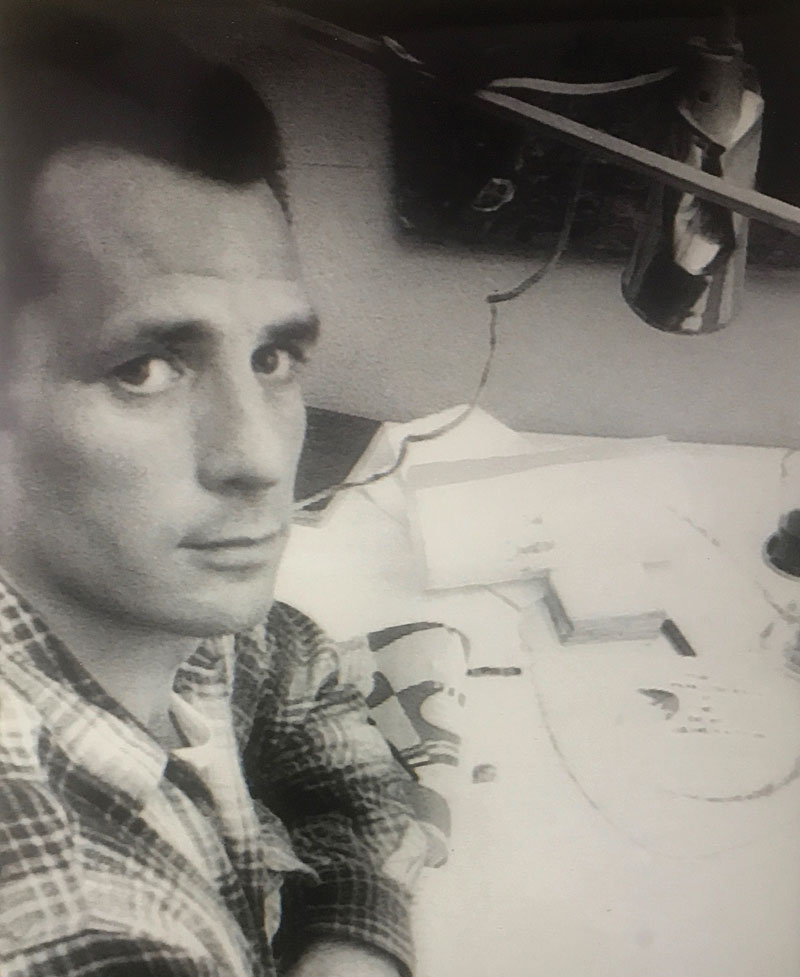

A series of black-and-white photos from a mid-1950s magazine article, which shows him hovering over a portable typewriter, now hangs on the wall of the tiny bedroom where he worked, lending an atmosphere of literary industry to the apartment.

So does a well-worn, padded rocker that Kerouac may have used while ruminating. A hobbit-sized back door opens onto a citrus orchard where he foraged for tangerines and sometimes spent nights sleeping under the stars.

It’s all very neatly maintained, though over time the bungalow has inevitably settled; there’s a steep enough tilt to the floor to test your sea legs. That’s why some TLC is needed.

“The house is sinking in the back,” says Vanessa Blakeslee, a local fiction writer and Rollins College adjunct instructor who’s a Kerouac Project volunteer. “Our challenge these days is making Central Floridians more aware of its historic import — and finding funds to stabilize the home.”

Maintenance, utilities and operating expenses of the nonprofit enterprise are covered by application fees for the residency program and rental income from a second house on the property. That’s not enough for larger expenses.

This decade will mark several anniversaries for the Kerouac Project. The residency program has been in operation for 20 years. The bungalow itself will celebrate its 100th birthday in 2025.

And all you have to do is to take another look at that historic marker to realize that we’re fast approaching an even more significant milestone: the century mark of Jack Kerouac’s birth.

For information about the Kerouac Project and how you can contribute, visit kerouacproject.org. I can’t think of a better way to celebrate these Kerouac-related anniversaries than by helping to shore up the bungalow that served, however briefly, as the author’s refuge.

Michael McLeod, mmcleod@rollins.edu, is a contributing writer for Winter Park Magazine and an adjunct instructor in the English department at Rollins College.