The death of a 91-year-old man is never truly a surprise. So when word came last October that Thaddeus Seymour, 12th president of Rollins College and arguably the most beloved citizen of Winter Park, had passed away following a year of precarious health, the reaction was grief, naturally, tempered by gratitude for a life well lived.

Even so, and despite ample time to prepare for the inevitable, it quickly became apparent that the community simply wasn’t ready to let him go — at least not yet. Shared one poster on social media: “It feels like someone turned out a light.”

Exactly. Of the hundreds of tributes Seymour received in the coming days, none better described the collective realization that this giant of a man — whose booming voice and irrepressible spirit were as integral to the city as its lakes, its brick streets and its cultural institutions — was truly gone.

But Seymour’s influence will be felt for generations to come, in ways large and small. He directly impacted many thousands of lives through his long career as a college administrator and later as a civic activist whose interests ranged from historic preservation to affordable housing. His effectiveness in those roles was magnified by his humor and humanity.

So genuine was Seymour’s ebullience that nearly everyone who met him left the encounter feeling better about themselves and more hopeful about the world in general. “Let’s face it: Thad was a quick read,” says Billy Collins, the former two-term U.S. Poet Laureate and now Senior Distinguished Fellow at the college’s Winter Park Institute.

“It took only a minute of exposure to the man to be pulled into the magnetic field of his spirited personality,” adds Collins, whose witty and gently profound poetry Seymour enjoyed and sometimes shared with friends on typewritten, laminated cards. “To be in his company was to be uplifted and enlivened; you couldn’t help bring a little bit of his brightness away with you.”

Inspirational personalities, though, aren’t always effective administrators. Not so with Seymour, who was without question among the 135-year-old college’s most consequential presidents. He placed the struggling institution on sound financial footing while reinforcing its traditional liberal arts mission during an eventful 12-year stint that ended when he stepped down — but not away — in 1990.

Fortunately for Winter Park, Seymour would spend nearly three additional decades lavishing attention on the community.

Seymour and his wife, Polly, were named Citizens of the Year by the Winter Park Chamber of Commerce in 1997. But the award would have been just as appropriate the following year — or in any of the 20-plus productive years still to come.

Winter Parkers who agreed on little else remained united in the belief that the Seymours — whose 71-year marriage appeared to have struck an ideal balance between romance and friendship — were community treasures. Even when Seymour publicly endorsed candidates for city commission, no one questioned his motives.

“I always appreciated Thad’s thoughtfulness, his consideration and his role as a valued statesman of Winter Park,” says Mayor Steve Leary, who knows a thing or two about how rough-and-tumble local politics can be. “He took this status seriously and was always a gentleman to all parties — regardless of your position on a topic.”

If there was a dark side to Seymour, he never showed it in public. “Dad was pretty much the same guy in every setting,” says Thaddeus Seymour Jr., eldest son and now acting president of the University of Central Florida, who describes his father as“a mentor, a great moral compass and a best friend.”

Dinnertime conversations at the Seymour household, he recalls, were often prompted by one of his father’s favorite questions: “What was your best thing today?” The premise — that whatever else may have happened, there was always something for which to be grateful — epitomized Seymour’s view of the world.

“I’ll forever cherish the fact that I got to have a dad like that,” says the younger Seymour, one of four surviving siblings including son Sam and daughters Liz and Abigail. “Yes, he understood that his words carried weight. But he had such genuine humility. He would be surprised by the outpouring.”

TADDEO THE GREAT

Thaddeus Seymour, born in New York City in 1928, was the son of Lola Virginia Vickers and Whitney North Seymour, assistant solicitor general in the Hoover administration and later president of the American Bar Association.

As a child, Seymour was fascinated by magic and frequented Manhattan’s Tannen’s Magic Shop — which was founded in 1925 and remains in operation.

He honed his sleight-of-hand skills, and as a young man spent a summer traveling the carnival circuit with his equally tall older brother, the late Whitney North Seymour Jr., who would become U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York.

“[Magic] has been a happy part of my life,” said Seymour — who dubbed himself “Taddeo the Great” when performing solo — during a lengthy 2005 oral history interview for the college’s Olin Library. “And part of the fun is, it’s intended to bring people pleasure. There’s nothing unkind about it. Nobody loses in magic.”

Seymour attended private schools as a youngster and enrolled at Princeton University in New Jersey when he was just 16. He unceremoniously flunked out after a year, but excelled as an athlete on the school’s nationally ranked crew team.

After a year of “growing up and getting my bearings,” Seymour returned to Princeton and did well. He might have graduated from there, but chose instead to marry Polly Gnagy, his childhood sweetheart. Because Princeton didn’t allow married students, the couple moved west, to be near Polly’s family.

Seymour enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley and completed an undergraduate degree in English literature. He earned a master’s degree and Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill after completing a dissertation called “Literature and the South Seas Bubble.”

The bubble in question was a 1720 financial crash in Great Britain. “It’s a wonderful graduate topic because nobody knows anything about it,” said Seymour. “I discovered in my little paper that some major literary figures had had an association with it. It was great fun.”

In 1954, Seymour became an English professor and later dean of students at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, where in the turbulent 1960s protestors tried to shout down a speech by Alabama Governor George Wallace and later surrounded and jostled the vehicle in which Wallace was being driven.

Seymour, certainly no fan of Wallace’s, issued a public apology, regretting that “certain Dartmouth undergraduates so flagrantly abused the cardinal principle of an academic community by infringing on your rights as a guest on our campus.”

In 1969, students occupied the administration building to protest the Vietnam War and the on-campus presence of an ROTC chapter — which was, ironically, already being phased out. Working behind the scenes, Seymour had agreed in advance to allow his ejection from the building by protestors.

“I had already signed a contract at Wabash,” said Seymour, referring to Wabash College, where he had been named president. “I was the youngest and biggest, and it sort of fell to me to be the one who was forcibly evicted.”

At that point, it was determined, the college would seek an injunction barring further occupation of the building. Police would be called only if the students violated a court order by refusing to leave. And even then, negotiation would replace confrontation.

A grainy news photograph shows a young man hustling the compliant — and seemingly bemused — dean from his office. At a muscular 6-foot-5, Seymour, a volunteer coach of the university’s crew team, dwarfs his spindly captor.

Students — including members of the militant Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) — and authorities orchestrated an anticlimactic exit that resulted in 45 erstwhile occupiers being charged with criminal contempt and serving 30-day jail sentences.

Seymour remained proud of the fact that, unlike similar situations at campuses across the U.S., the Dartmouth incident wasn’t marred by bloodshed. “No violence, no tear gas,” Seymour said. “It came out as it should have.”

Dartmouth’s deft handling of a potentially incendiary situation won praise from a New Hampshire representative in the Congressional Record. But Seymour, although he was sympathetic to the students, later admitted that the incivility on display troubled him deeply.

Nearly 50 years later, in 2018, Seymour reconnected with the young man in the photograph. David Green, now a Boston-based national distributor of water filtration systems, visited the Seymours in Winter Park and dined with them at their home on Lake Virginia.

“David has been a special teacher,” Seymour later posted on Facebook. “His friendship has taught me the importance and the rewards of reconciliation.”

Wabash College, a small (800-student) all-male liberal arts college in Crawfordsville, Indiana, was an ideal fit for the congenial Seymour. “Very personal, very good humored,” he said. “[Our children] grew up in a traditional Midwestern county seat … a small town in a county that exports more corn and hogs than any county I can think of.”

But, although Wabash was a more placid place than Dartmouth, it wasn’t lost on Seymour that the college had run through five presidents in six years, one of whom had suffered a nervous breakdown and one of whom was “a fancy guy” who had been hired from Harvard and had failed to adapt to the down-home culture.

Noted Seymour: “More than anything else, [Wabash] wanted a sense of self-worth and a sense of stability and continuity. And that’s exactly what I wanted after what we’d been through.”

The laid-back ambiance at Wabash allowed Seymour’s more whimsical side to come to the fore. A lover of distinctive if sometimes eccentric college traditions, he started a holiday called Elmore Day to honor a notoriously bad Indiana poet named James Buchanan Elmore.

As part of the festivities, to which townspeople were invited, Seymour would read aloud Elmore’s florid works — including “The Wreck of the Monon” and “When Katie Gathers the Greens” — at an outdoor assembly. He was also prone to bound from the bleachers and lead raucous, fist-pumping cheers at basketball and football games.

But Seymour’s tenure at Wabash was all business when it needed to be. During his nine-year presidency, he raised nearly $32 million during one two-and-a-half-year span — said by The New York Times to have been “the most successful small college campaign in the history of higher education.”

Then in 1977, Seymour told the trustees that he would be leaving in 1978, the year of his 50th birthday. He didn’t yet have another job but “had begun to fantasize about what to do next; about what adventure would be right for us.”

Many prestigious institutions were interested in talking to the quirky but charismatic leader who had brought support and stability to an out-of-the-way college in the rural Midwest — and not only colleges were calling. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art also interviewed Seymour for its presidency.

But Rollins proved particularly intriguing because it faced many of the same challenges as had Wabash. “I would have to say,” Seymour recalled, “as I look at my career in education, all of that was simply preparation for Rollins.”

Seymour was amused — and likely not surprised — to learn that the first action taken by the Wabash faculty upon his departure was to eliminate Elmore Day.

BIG MAN, BIG IDEAS

When Seymour arrived in Winter Park in 1978, he was described by the Orlando Sentinel as “about as different from his predecessor as a Hush Puppy is from a patent-leather loafer.”

The previous president had been Jack Critchfield, a button-down personality who went on to a successful career in private business, becoming president of Winter Park Telephone, then group vice president and ultimately CEO of the $3.5 billion Florida Progress Corporation (whose subsidiaries included Florida Power).

Seymour was likely not displeased with the oddly apt comparison to casual footwear. He, in fact, often wore sneakers with his khakis and blue blazer (he also favored bowties) and quickly energized the campus with his larger-than-life personality.

“If you’re going to be a liberal arts college, you’ve got to be a liberal arts college,” was Seymour’s mantra as he sought to lift the somewhat threadbare institution out of the financial and intellectual doldrums.

“When I saw [Rollins], I saw a physical plant in quite serious disrepair,” said Seymour. “I saw a place that was embarrassed by its Jolly Rolly Colly reputation. I saw a place that needed to feel loved. It needed to feel good about itself.”

Seymour, looking ahead to the college’s centennial, appointed the blandly labeled College Planning Committee in 1978. The group — led by Daniel R. DeNicola, dean of education and associate professor of philosophy — would spend the next year and a half evaluating programs and setting a five-year institutional agenda.

By 1985, its centennial year, Seymour wanted Jolly Rolly Colly to be nothing less than “the finest small college in the Southeast, standing among the finest small colleges in the country.”

“We felt very strongly that in the planning process we needed to be clear about what liberal arts education was,” said Seymour. “Liberal arts education was not the majority of your students studying business and the second-largest group studying communication, which is what was going on.”

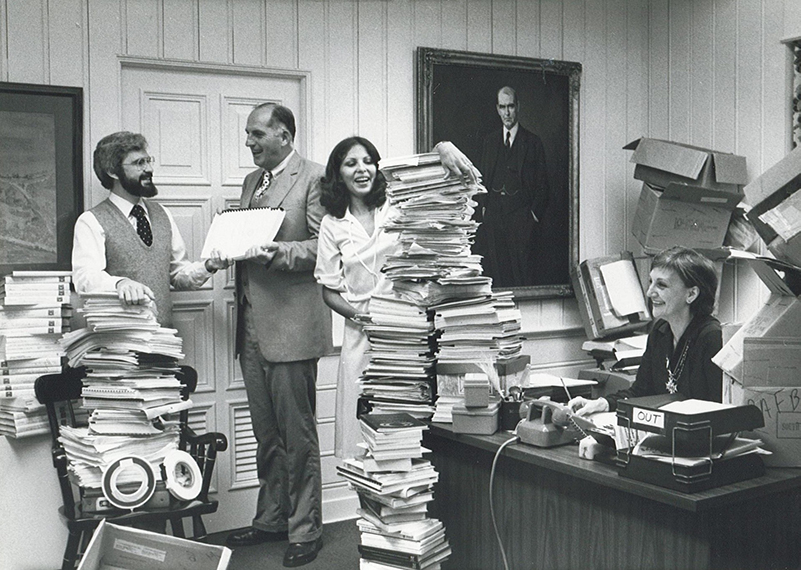

When the 500-page Report of the College Planning Committee was released in October 1980, its most daring recommendation was to eliminate the popular undergraduate business administration major — a move that pleased liberal arts purists but, not surprisingly, displeased students majoring in business administration.

“Any time you have a shift in an organization, you have naysayers,” says Seymour Jr. “Dad used to say that moving a college is like moving a cemetery — you get no help from the inhabitants.”

Business administration, the report concluded, was rightly a graduate-level subject. If the undergraduate program was dropped — except as a minor — then the Crummer Graduate School of Business could seek accreditation from the prestigious Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. (AASB accreditation was granted in 1985.)

“Dad had a vision for Rollins,” adds Seymour Jr. “He was so confident in the future of the place that he stayed true to that vision. When that happens, obstruction eventually melts away.”

In 1987, a Master of Liberal Studies program was introduced and the School of Continuing Education — where the curriculum had been revamped to be more reflective of the traditional day school — was renamed the Hamilton Holt School in honor of the college’s legendary eighth president.

As the 1980s wound down, Seymour could look back over a decade of successes. A $33 million capital campaign was successfully completed, and the college’s endowment doubled, to nearly $20 million. Faculty salaries had risen by 80 percent.

Olin Library was built with a $4.7 million grant from the Olin Foundation. Other physical plant additions and improvements included Cornell Hall ($4.5 million), Alfond Stadium ($1.5 million) and a renovation of Mills Memorial Hall (now Kathleen W. Rollins Hall) as a learning resource center and student government offices ($1.8 million).

Four endowed chairs were added: Classics — a favorite of Seymour’s, who delighted in its popularity — Latin American and Caribbean Studies, English Literature, and Finance in the Crummer School. Time, Newsweek and U.S. News & World Report now covered the college not for its controversies or its gimmicks but for its academic prowess.

The business administration major returned in 2011. Generally, however, the trajectory set by Seymour has continued through today, with Rollins ranked No. 1 among regional universities in the South in U.S. News & World Report’s 2020 rankings of “Best Colleges.” It has been ranked No. 1 or No. 2 for 25 consecutive years.

“Thad was larger than life,” says Rita Bornstein, who succeeded Seymour as president in 1990. “He was a big man. He thought big, he acted big, and had big ideas and ambitions. Thad pulled and pushed Rollins to be better and better. That’s his legacy.”

Bornstein recalls that following Seymour’s retirement, when he began a new career as an English professor, he asked her for a favorite poem that he might share with his incoming group of freshmen.

She selected a work by Marge Piercy, “To Be of Use,” which he loved and shared widely on one of his laminated cards. “I still cherish mine,” says Bornstein, who adds that the words remind her of Seymour’s time at Rollins:

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart,

Who pull like water buffalo, with massive patience,

Who strain in the mud and the muck to move things forward,

Who do what has to be done, again and again.

It’s unknown how many such cards are still nestled in purses, wallets and dresser drawers. But Seymour surely dispensed many hundreds featuring favored poems, including “Dust of Snow” by Robert Frost. If “To Be of Use” described Seymour’s work ethic, then “Dust of Snow” explained his eternal optimism, without which he could never have accomplished so much:

The way a crow

Shook down on me

The dust of snow

From a hemlock tree

Has given my heart

A change of mood

And saved some part

Of a day I had rued.

SUDDENLY SEYMOUR

It didn’t take long for the campus and the community to get a sense of Seymour. During the first year of his presidency he revived Fox Day, a whimsical all-campus holiday declared spontaneously each spring at the president’s discretion. Fox Day, established in 1956 by President Hugh McKean, had been eliminated in 1970.

“It was understandably a very frivolous activity at a time when the nation was addressing the war,” Seymour said. “If you took a day off, it was to talk about a moratorium for peace or address substantive moral issues. When the Vietnam War ended, we didn’t have to feel guilty about having fun again.”

Later that year, Seymour was compelled to defend freedom of expression when the city threatened to arrest director Jeff Storer and actors David McClure and Darla Briganti from the cast of Equus, which contained a 10-minute nude scene. The play was slated to open within a few weeks at the Annie Russell Theatre.

The brouhaha began when the Orlando Sentinel ran a story about the notably muted response from season subscribers, who had been alerted in advance to the nude scene. “I have faith in the maturity of our audience,” Storer told reporter Jody Feltus, who also quoted Seymour as being supportive of the production because the college “is an intellectually free environment.”

But when about a dozen people lodged complaints, city officials vowed to enforce a vague 1912 ordinance that prohibited nudity and, strictly speaking, would have made bathing in one’s home illegal. In response, about 400 students marched on City Hall and draped a nude statue with panties and a bra.

On May 3, Seymour, who had earlier that day reluctantly agreed to order the troublesome scene altered, presided over an all-campus meeting during which he announced a change of heart. He now expressed support for performing the play as written, and promised legal representation for anyone arrested.

Still, did anyone really have to go to jail? Because the city attorney and the college attorney — Richard Trismen — were one in the same, Seymour asked legendary local lawyer Kenneth Murrah, who had volunteered to help the college, about going to court and seeking a restraining order against the city.

On May 4, just hours before the curtain was set to rise, U.S. District Judge John A. Reed presided over a hastily called hearing. Ironically, Reed had two tickets for Equus and wondered aloud if this conflict of interest should prevent him from ruling at all.

Attorney Lee Sasser, an associate of Murrah’s, said: “Your Honor, Dr. Seymour, president of Rollins, is in the courtroom, and I know if you requested it, he would fully refund your tickets for tonight.” Replied Reed: “OK. But you’ll have to explain this to my wife.”

The judge issued a temporary restraining order that allowed the show to go on without immediate legal consequences for the participants — but he did not, as the college had hoped, rule that the ordinance was unconstitutional. Theoretically, arrests could be made later, when the order expired. Ultimately, however, neither party pursued the matter further.

That night, Seymour noted a handful of picketers on campus led by Rev. John Butler Book, a fire-and-brimstone fundamentalist who led a small church in Winter Park. “I remember one of the signs distinctly,” he said, always laughing when he repeated the story. “It read, ‘Seymour Wants to See More!’”

While shaping the college’s future, Seymour also bolstered appreciation for its past. He oversaw renovation of Pinehurst Cottage, the campus’s oldest building, and had it placed on the Winter Park Register of Historic Places.

In addition, he revitalized and rededicated the neglected Walk of Fame, which had been launched in 1929 by President Hamilton Holt, and added commemorative stones for such diverse figures as folklorist Zora Neale Hurston, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Chief Osceola, leader of the Seminoles.

In 1985, Seymour presided over the college’s yearlong centennial celebration, which he later described as “the most fun I ever had.” It began with the dedication of Olin Library and continued through the ensuing months with such activities as picnics, performances and panel discussions.

But of the most significance to Seymour was the college’s centennial-year decision to divest from companies that did business with apartheid-era South Africa. On the day of the trustees’ annual meeting, students called attention to the hot-button issue by setting up shanty-style housing on the Mills Lawn. Trustees had to walk past the makeshift village to get to Mills Memorial Hall.

“Now, for Rollins that was big,” Seymour recalled. “And I was so proud of that part of the coming of age — not just of shedding the Jolly Rolly Colly [image] … not just of being in U.S. News & World Report, but of having the conscience to act out of a principle about the endowment.”

However, most students and community members have memories of Seymour that are more related to personal interactions. “Dad Thad” — a moniker that was also used at Princeton and Wabash — was a peripatetic presence on campus and in the community.

But Seymour was also an easily accessible administrator who was never too busy for a private chat with anyone who wanted to see him. Perhaps more accurately, he was nearly always too busy — but made time regardless.

And he carried around silver dollars to bestow upon surprised students whom he had spied doing a good deed — even something as simple as picking up trash. “It didn’t count if they saw me coming and faked it,” he insisted.

Seymour seemed entirely lacking in presidential affectations. He washed cars, led square dances, marched in parades and even donned tights to portray King Arthur in the Rollins College Renaissance and Baroque Festival. He also performed his magic act at the beginning of each academic year during a show staged at the Annie Russell Theatre by the Rollins Players.

The student ensemble usually introduced Seymour by singing “Suddenly Seymour,” from the stage musical Little Shop of Horrors. “The words were just so perfect,” says Alice Fairfax, a theater major who is today public relations manager at the Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts.

Suddenly Seymour, is standing beside me.

He don’t give me orders, he don’t condescend.

Suddenly Seymour, is here to provide me,

sweet understanding, Seymour’s my friend.

Often, Seymour personally conducted campus tours for groups of potential students. Fairfax, who lived in Lyman Hall on the third floor overlooking Mills Lawn, remembers one Saturday morning in 1985 when she overhead a distinctive voice extolling the college’s virtues and opened her window to see what was happening.

Seymour, who happened to glance upward, spied Fairfax and immediately decided that an impromptu scene from Romeo and Juliet would enliven the proceedings.

“He didn’t miss a beat, and called out to me, ‘But soft, what light through yonder window breaks?’” recalls Fairfax, who was, of course, expected to respond as Juliet with, “O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?” Taken by surprise, however, she didn’t remember the lines.

Seymour later typed the iconic exchange on a three-by-five card and instructed Fairfax to tape it to her window so she would be prepared the next time. “Anytime he was leading a tour, I would be at my open window and we would do the scene for prospective students,” says Fairfax, who still carries the card as a memento.

When Seymour stepped down from the presidency in 1990, he simply said that “it’s time for a change at Rollins College, which deserves new ideas and inspirations, new vision and leadership. It’s also a time for a change for me.” He would return to the classroom, he said, and teach English.

It was assumed that Seymour, as befitting a former president, would choose to lead a handful of workshops for advanced students. Instead, he tackled freshman English courses — which in short order were wait-listed because of their popularity.

For a semester, Seymour was part of a “master learner” program in which he took biology and pre-calculus courses with undergraduates. “I want to see if there’s still a tune left in the old violin,” said Seymour when asked why, at age 63, he would try to master subjects that had bedeviled him as a young man. He was proud of the B’s he earned.

Seymour ultimately spent 14 post-presidential years at the college as a part-time professor. “I was able to devote myself … totally to what I’d set out to do in the first place,” he said when he formally retired in 2005. “I couldn’t be more grateful for the privilege. I mean that.”

CITIZEN THAD

For Seymour, “retirement” meant lavishing even more attention on Winter Park. “Those involved in education should demonstrate to their students concern for their communities,” he said. “It’s the best form of teaching by example.”

Throughout his career, wherever he lived, Seymour made it a point to become a stalwart of civic life. In Winter Park, among many other volunteer committees, he chaired the board of trustees of the Winter Park Public Library, and in 1995 helped Polly found the library’s New Leaf Bookstore, now named in her honor.

Later, Seymour was energized by an effort that seemed to call for the skills of a magician. In order to save the Capen-Showalter House from demolition, funds had to be raised to float the historic residence — via barge and in pieces — across Lake Osceola to the grounds of the Albin Polasek Museum & Sculpture Gardens, where it would be reassembled and restored.

Preservation Capen, co-chaired by Seymour and former State Attorney Lawson Lamar, rallied the community and the relocation was completed in 2013. Two years later, the circa-1885 home was opened as a community events center.

For many, spearheading such an audacious effort would qualify as a legacy project. But for Seymour, dozens of less showy homes built by Habitat for Humanity of Winter Park-Maitland were even more important. Seymour chaired the worldwide nonprofit’s local affiliate since it was started in 1993.

Seymour’s involvement originated with Hal George, founder of Parkland Homes and a 1976 Rollins graduate, who had been concerned about the lack of affordable housing in and around Winter Park.

“From the very beginning, Thad was our leader and our public face,” says George, who still serves as president of the organization. “He could be found on work sites, chairing our board meetings, raising funds for homes and doing anything that was needed to ensure our success.”

Seymour also presided over the heart-tugging ceremonies when ground was broken and homes were completed — consistently awing the low-key George with his effortless eloquence.

“Thad was truly magical,” says George. “Not only because he was a magician, but magical in the sense that he made things happen — and he inspired people to do things they didn’t know they were capable of doing.”

Accolades continued to pile up in recent years. Seymour was a finalist for the Orlando Sentinel’s Central Floridian of the Year in 2013. And the Seymours were individually named to Winter Park Magazine’s Most Influential People list: Thad in 2015 and Polly in 2017.

“Frankly, I never thought of myself as influential, except that I’m pretty tall and have a loud voice,” said Seymour when accepting the magazine’s award. “It was the role of college president that provided the influence. I always tried to take that seriously because the college is, and always has been, such an essential part of the character of the community.”

The Seymours dealt forthrightly with an unthinkable tragedy in 2014 when their daughter Mary, 56, a mental health counselor and gifted writer who had for years struggled with bipolar disorder, took her own life in North Carolina using a gun that she had legally purchased earlier that day.

Another daughter, Liz, wrote movingly about the loss of her sister in the Triad City Beat, a respected alternative newspaper distributed in Greensboro and Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The article frankly described Mary’s illness and delivered an indictment of the porous process that allowed her to so easily obtain a gun license.

“That was the hardest part of my dad’s life,” says Seymour Jr. “But there was no hesitation on his part when it came to speaking out. He wanted something constructive to come of it.” Several times, the elder Seymour posted a Facebook link to Liz’s article along with a brief but urgent plea — most recently last September.

“I just learned that yesterday was Gun Suicide Day,” he wrote. “It was reported that there were 800 gun suicides last year. Our dear Mary died that way, and I feel compelled to post again this powerful article by our daughter, Liz. I hope you will take the time to read it. We must take action.”

In 2016, the entire community got an opportunity to thank the Seymours, who were told that they had been invited to a “unity party,” the purpose of which was to heal divisions that had resulted from a contentious city election. Of course, they probably knew better.

But they were gracious enough to attend anyway — and to feign surprise when it turned out that the party, attended by hundreds on the grounds of the Polasek Museum & Sculpture Gardens, was to honor them.

In fact, the “unity party” descriptor wasn’t entirely untrue. Affection for the couple had been a nonpartisan issue in the community for decades. “Thad was the most go-to guy in this town,” says public relations executive Jane Hames, who was the volunteer president of the Winter Park Chamber of Commerce when Seymour was hired by Rollins.

Locals had respected the conservative, corporate style of Jack Critchfield, says Hames. But the buoyant Seymour, she notes, was almost immediately both respected and loved — “and he responded in kind by giving himself to us all.”

Hames recalls Seymour’s favorite admonition to fellow community volunteers: “Do you know the difference between being involved and being committed? If you had bacon and eggs for breakfast this morning, the chicken was involved — but the pig was committed.”

The “surprise” celebration, which Hames dubbed the Seymour Family Reunion, involved support from 21 local nonprofit organizations whom Hames had asked to participate. It was certainly not a hard sell: “Whoever I was on the phone with, the result was that we both cried.”

Under a tent facing Lake Osceola, the crowd listened to a Dixieland jazz combo, enjoyed tricks from strolling magicians, feasted on catered cuisine and shared seemingly countless stories

The Seymours, at turns deeply moved and laugh-out-loud entertained by a series of sometimes tongue-in-cheek (but always sincere) speeches, accepted one plaudit after another with their usual combination of modesty and good humor.

During the event, Winter Park Mayor Steve Leary declared May 1 Thaddeus Seymour Day. Rollins President Grant Cornwell presented the couple with a framed silver coin of the sort Seymour randomly handed out on campus when rewarding good deeds.

Debbie Komanski, executive director of the Polasek, gave Seymour a small replica of Man Carving His Own Destiny, a sculpture on the property. The figure, she said, represented Seymour’s indomitable spirit — which she observed firsthand during the Capen-Showalter House campaign.

Hal George announced that the next Habitat for Humanity home built in Winter Park — the 53rd overall — would be dubbed the Thad Seymour House. “We’ll try to do a better job on that one,” deadpanned George.

And Diana Silvey, then program director for the Winter Park Health Foundation (now vice president of programming for the recently opened Center for Health & Wellbeing), noted that Seymour had been a longtime volunteer for the organization. But, she added, “we know that the wind beneath his wings this whole time has been Polly.”

Without much prompting, Seymour was persuaded to sing “The Dinky Line Song,” which dates to the 1890s and bemoans the notorious unreliability of the ramshackle railroad that ran between Orlando and Winter Park and had a Victorian-style depot on Ollie Avenue, near today’s Dinky Dock Park on Lake Virginia:

Oh, some folks say that the Dinky won’t run.

But listen, let me tell you what the Dinky done done.

She left Orlando at half past one.

And she reached Rollins College at the setting of the sun.

Seymour had belted out that delightful ditty dozens if not hundreds of times at community presentations, campus gatherings or just for friends. It was silly, of course, but it was also an homage to local history. No wonder he enjoyed singing it so much.

He had even performed “The Dinky Line Song” backed by a rock band. Chip Weston, a local artist and activist, recalls playing a set with his combo in Central Park as part of a fundraiser during the Capen-Showalter House campaign. Says Weston: “Thad came onstage and did the song with great aplomb.”

THE NEXT ADVENTURE

During the past several years, both Seymours had been hospitalized for an array of age-related illnesses. They were frustrated when they were unable to participate in civic events but lovingly tended to one another at their home in Westminster Winter Park.

Then, as the old magician began to inexorably fail, his family gathered around him to help ease his transition to the next adventure. Yet, at times Seymour rallied. Just days before his death, he asked Hal George to arrange a meeting with Winter Park Magazine to encourage more publicity for upcoming Habitat for Humanity projects.

On October 21, Liz Seymour posted an update about her father’s condition on his Facebook page — and Winter Parkers began to steel themselves for the inevitable:

“Please send a loving thought to my parents as they come to the end of their long and wonderful partnership. My dad is very weak and under hospice care; my mother spends a lot of time lying next to him in bed holding his hand. He is as sweet and funny and loving as ever, but tired. I’m down in Florida with them, so grateful for this precious, tender time together.”

Seymour, unrivaled as Winter Park’s First Citizen, slipped peacefully away five days later, enveloped by love from his large extended family and from the communities where his presence still resonated decades later — including Princeton and Crawfordsville.

“Thad was a great man and a great president of Rollins,” says Allan Keen, a 1970 Rollins graduate who was appointed to the board of trustees by Seymour in 1989. “His large physical presence and love of the liberal arts, guided by his warm and sincere personality, made a mark on the college and its history.”

Adds President Grant Cornwell: “Thad has been a friend and mentor since the moment I accepted the position [at Rollins]. It was so good to be able to talk about the history of the college and current issues with one who shared a love for the institution and profound optimism for its future. I valued Thad as a wise counselor and as one of the kindest, most good-hearted people I have ever known.”

Billy Collins, as expected, describes Seymour using poetry — more specifically William Wordsworth’s “The Rainbow,” which contains the much-quoted line “the Child is father of the Man.”

“[The phrase] is shorthand for the thought of the poem, which is the poet’s wish that his heart will continue to leap up in adulthood as it did in his childhood,” says Collins. “The child will teach the man how to do this — how to sustain this spontaneous love of his natural environment.”

Adds Collins: “There was a lot of child in the man Thaddeus Seymour. His enthusiasms were often as boisterous as a child’s. If something caught his interest, he was all in. His energy was contagious. ‘Come on with me,’ he seemed to say like a benevolent Pied Piper. ‘You’ll feel better about yourself if you get off the bench and onto the playing field.’”

Collins — who, like Seymour, began his career as an English teacher — recalls an observation from William Carlos Williams about poetry: “Men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.” Seymour, says Collins, was not one of those men. “He died suffused with poetry.”

My father teaches poetry

to yawn-eyed college students

who think T.S. Eliot

is some kind of department store.

He captures their attention

with the skill of a magician —

Now you see it, now you don’t —

teaching them the fleeting ways

of symbol and metaphor.

My father didn’t read poetry

until later in his life

when the solid stomp of prose

finally failed to rouse him.

He sought out a frailer form,

wisped and condensed,

fraught, metered, and sly —

with new-gathered understanding

that life was knowable as light.

My father sends poetry

to his friends and children,

letting the words of Whitman,

Frost, Collins, Dickinson,

speak the meter of his heart,

the depth and breadth of feelings

too precious to commit

to ordinary words.

My father is poetry

as he rises each day,

beginning fresh stanzas

without regretful glance

at limping rhymes or scuttled lines,

moving forward with the measured speed

of a life-lived, graced

with the language of joy.

— Mary Seymour, 2002

This poem was read aloud at Seymour’s memorial service by his granddaughter, Maddie Seymour, daughter of Thaddeus Seymour Jr. and Katie Glockner Seymour.

A Pretty Good Magician for a College President

By Daniel R. DeNicola

I had the great pleasure of working with Thad Seymour in various positions in academic administration and institutional planning during the years of his presidency. From the outset, I had great respect for his leadership — and it is one of the great privileges of my life that we developed a close, lifelong friendship through those years. What I owe him, personally and professionally, is enormous.

He touched — and shaped — so many lives. I have known many college presidents, but I have never known anyone to get more joy, more pure fun, out of doing the work of the presidency.

Thad loved the idea of building each year’s class and believed that among the diversity of the academically gifted, we should always have a banjo player, a magician and singers to form a glee club. For a while, he kept a balloon-inflating machine in his office. He always kept a pocket of silver dollars to give spontaneously when, unobserved, he witnessed someone pick up litter on campus.

His smile and knee-smacking laugh were contagious. He clearly adored Polly and generously shared his family. He also loved his magic. He once considered adding a motto to his business card: Should it read, “A pretty good magician for a college president,” or the reverse?

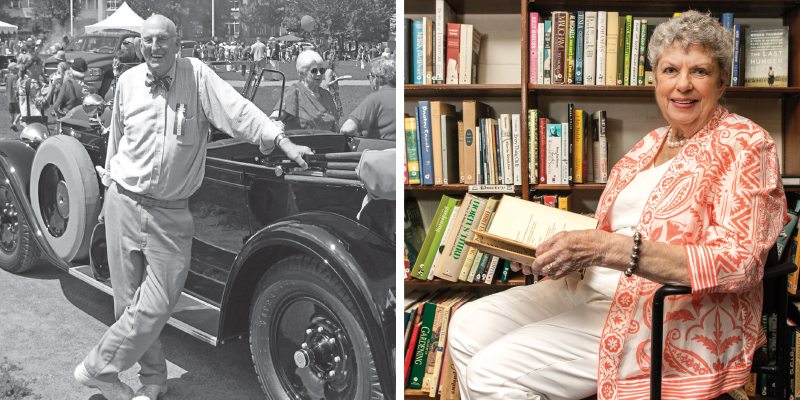

From early on, Thad loved convertibles — including the family’s heirloom 1929 Packard touring car and his well-worn VW Beetle. He also loved the rituals of holidays and celebrations, and reinstated Fox Day at Rollins to encourage every member of the college community to enjoy the beautiful setting and the wonderful people on campus.

Not all plans worked, of course. Thad wanted a Latin diploma for Rollins undergraduates, and we worked together with a classicist — deciding, for example, whether the student “earned” or the faculty and trustees “bestowed” his or her degree. But student reaction suggested that we would need to print an English version as well.

Thad also wanted the diploma to be on genuine parchment vellum. But true parchment, we learned, is amazingly expensive. And it involves sheepskin, which brought the proposal to the attention of animal-rights activists on campus. That, in turn, inspired Thad’s tongue-in-cheek proposal for a “Mostly Mutton Concert” with a program ranging from “Sheep May Safely Graze” to “It Had to be Ewe.” Ultimately, no lamb was skinned.

When Thad had just arrived at Rollins, a solicitous assistant wanted to be sure the new president would be pleased with the arrangements for a formal dinner. She had many questions and kept seeking decisions about the details: the decorations, the music, the seating, the meal.

After much discussion about the menu, she asked, “Do you want to have mashed or home-fried potatoes?” Thad replied, “You know, I have only two or three good decisions a day in me, and if I have to spend one of them on the potatoes…” The assistant got the message, and thereafter all he needed to say was “potatoes.”

A college president receives a lot of crank letters, and Thad once shared his technique for dealing with them — a technique I admit to having borrowed. He would write a simple letter of reply: “Dear ____: You may be right. Sincerely, Thad Seymour.”

Thad’s leadership was strong and gentle. A directive was rare; he was more likely to say, “If I were doing that, I would…” and the message was understood. Anger was unthinkable. He was a thoughtful optimist; he trusted and entrusted — and you wanted to be worthy of that trust.

Though Thad had a keen institutional vision, amazing writing and speaking skills and impressive accomplishments throughout his long career, what made him so special was a deep if light-hearted wisdom, a sense of what really matters — in the college, in the community and in life.

I am so grateful to have these and so many more cherished memories of Thad and of Polly. I still see him, greeting arriving guests at his home by throwing open the door, and in that hearty voice, booming, “Welcome, friends!”

Dan DeNicola is professor emeritus of philosophy at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. He came to Rollins in 1969 as an instructor of philosophy and eventually became dean of the faculty and later provost before chairing the Department of Philosophy and Religion until 1996, when he became provost at Gettysburg College. At Rollins, DeNicola also chaired the College Planning Committee formed by Seymour in 1979 to clarify the college’s mission and evaluate its programs. Recalled Seymour in 2005: “In my 51 years in higher education, the person I have valued the most is Dan. Knowing how important planning was — and knowing that Dan was the brightest, most enlightened, most engaging person I have known in my professional years — I asked him to head the committee. I depended on him, I turned to him, I was guided by him, I was educated by him. I count him as the major figure in my administration.”

In Memorium

WENDY CHOIJI

Living well on borrowed time.

Beloved Central Florida news anchor Wendy Chioji, whose courageous public battle with cancer inspired untold numbers of people, lived in Winter Park from 1993 to 2008. During that time, she was often spotted working out at the Winter Park YMCA, jogging along Cady Way Trail or cheering for the Rollins College Tars men’s basketball team.

And it was a Winter Park-based company, Bolder Media, that ensured Chioji would continue to have a platform for her story — and for telling the stories of others — even after she relocated to Park City, Utah, to pursue a life of vigorous outdoor adventure and extensive world travel.

Chioji, who died in October at age 57, finally succumbed — but not before setting an example on how to live each day to the fullest. Her exuberance for life will be her legacy, says Marc Middleton, founder of Bolder Media Group and a former colleague of Chioji’s at WESH-Channel 2.

“Wendy’s words and her actions were a constant reminder of the beauty of life, the value of time and the importance of friendship,” says Middleton, whose company produces the Growing Bolder television and radio programs. “If we not only remember those lessons but actually live them — then Wendy continues to live on through us.”

A California native, Chioji grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland, and graduated from Indiana University with a degree in broadcast reporting. She joined WESH in 1988 as a reporter and eventually worked her way up to the anchor desk.

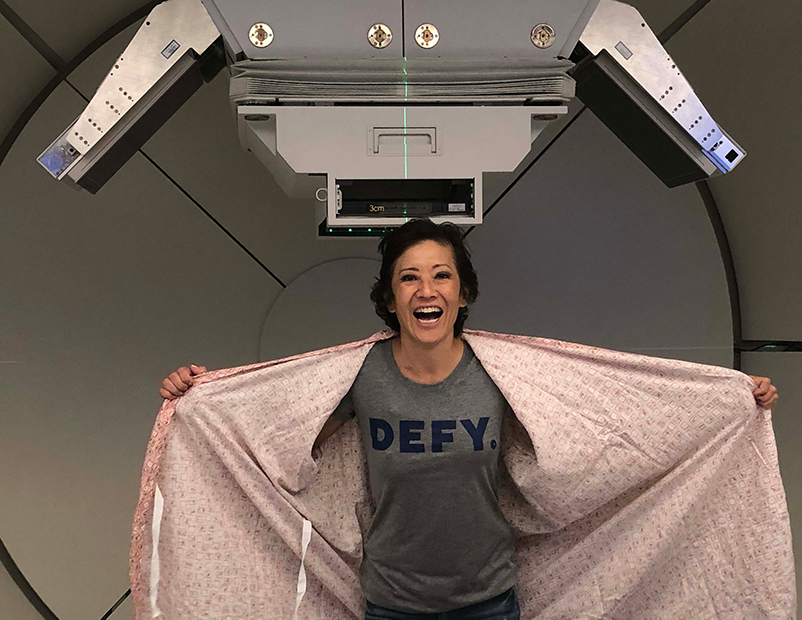

In 2001, she made a brave on-air announcement that she had Stage II breast cancer at age 39. Her response then, as it was for the rest of her life, was to battle the disease with all the strength and savvy she could muster while embracing life even more fiercely and joyfully.

After moving to Utah in 2008, Chioji swam, cycled and ran — completing five Ironman distance triathlons, dozens of half-Ironman distance races and shorter races of various kinds. Although it appeared that she had beaten breast cancer, a more devastating diagnosis came in 2013.

Chioji, a routine MRI had revealed, now had Stage II thymic carcinoma, a rare, aggressive cancer apparently unrelated to her previous bouts. Just a few weeks after undergoing radiation, chemotherapy and surgery, however, she and other cancer survivors and advocates climbed Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest peak in Africa.

Her zealous defiance of such punishing health obstacles made Chioji the perfect fit for Growing Bolder. She also co-anchored Bolder Media’s Surviving & Thriving show, a quarterly broadcast that chronicled the lives of people coping with various serious illnesses. It aired first on WKMG-Channel 6 and in 2016 moved to WESH.

The thymic carcinoma, which had initially responded to treatment, recurred in the fall of 2014. Chioji continued to fight — to “defy,” as she often put it — and was accepted into a clinical trials program at the National Cancer Institute in Maryland.

In her final blog, September 25, she recounted her chemotherapy at NIH, her fear of losing her hair, her sleepless nights, her fatigue, her refusal of hospice — and yes, her optimism and gratitude.

“I am grateful I have lived well on my borrowed time for five years this Labor Day,” she wrote. “I am hopeful I’ll borrow five more.”

Chioji was bolstered by the positivity of her legion of followers, and they were bolstered by hers. One of her closest friends was Mike Gonick, a broker associate with the Winter Park office of Premier Sotheby’s International Realty. He often joined her on overseas trips and was constantly amazed at her unflagging enthusiasm — and at her feats of daring.

“Wendy would bungee jump in Africa, when it looked like there was at least a 50 percent chance that you’d die doing it,” says Gonick. “She was never showing off, though. She was sending the message: ‘I’m doing this; what are you doing?’”

— Catherine Hinman

DEFY WITH WENDY

Wendy Chioji was a tireless fundraiser for Pelotonia, a nonprofit that raises money to fund innovative cancer research. It was this research that continued to give her hope and empowered her to live with passion and purpose. Growing Bolder is honoring Chioji’s wishes by producing a special edition T-shirt emblazoned with her personal mantra: DEFY. Proceeds will be donated in Chioji’s name to Pelotonia. You can buy a shirt at wendychioji.com.

LOU FREY

A bipartisan civic champion.

Former U.S. Congressman Lou Frey Jr. loved his family, his country and baseball. Although he was at times a national figure, Winter Park was the congenial consensus builder’s home base for almost 60 years prior to his death in October at age 85.

At their Genius Drive home on Lake Mizell, Frey and his wife of 63 years, Marcia, held ritual Sunday dinners that were open to their five children, seven grandchildren and assorted friends who enjoyed the company and the opportunity to engage in civil, informed discussions of pressing issues.

Frey, however, was sometimes known to sneak away to watch a ballgame on television. And who could blame him? He had certainly earned some down time.

During his five terms in the U.S. Congress, the results-oriented Republican had, by some accounts, made a billion-dollar-plus impact on life in Central Florida. But it was likely his passion for civic affairs and amiable discourse that most endeared him to the public.

For 20 years on 90.7 WMFE — first on The Notebook and then on Intersection — he bantered cordially with Democratic analyst Dick Batchelor, a former member of the Florida House of Representatives, about state and local politics. Voices were never raised, and listeners always learned something — not the least of which was that friends could still agreeably disagree.

Frey got things done through bipartisanship. “He was a bring-people-together congressman,” said former Democratic U.S. Senator Bill Nelson at a public memorial service, held at St. John Lutheran Church in Winter Park.

Julia Frey, his eldest child and an Orlando attorney, said her father believed that the surest path to a better world was through the next generation. “He was interested in getting kids educated, involved in the political process, involved in the community,” she says.

To that end, Frey founded the Lou Frey Institute of Politics and Government at the University of Central Florida to advocate for civic education and to encourage public awareness and engagement.

The New Jersey native, who was the first in his family to graduate from high school, once aspired to be a baseball coach. But after a stint in the U.S. Navy, he earned a law degree from the University of Michigan Law School.

Frey began his career in Central Florida, where his parents had earlier settled, in 1961 as the assistant county solicitor for Orange County. Longtime locals will remember his partnership in the law firm of Gurney, Skolfield & Frey, with offices on Park Avenue, and later Mateer, Frey, Young & Harbert, with offices in Orlando.

At age 34, Frey was elected to Congress, serving what was then the 5th but is now the 9th District for five terms from 1969 to 1979. During that time, he sat on the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee, the Science and Technology Committee and the Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control.

Frey was the first chairman of the Republican Task Force on Drug Abuse, and in 1969 helped author Congress Looks at the Campus with 22 other House members led by Representative William E. “Bill” Brock of Tennessee. The Brock Report became the basis for the 18-year-old vote and expansion of various college loan programs.

He was also a standout shortstop on the baseball team fielded by House Republicans and was named the GOP’s Most Valuable Player three times between 1968 and 1978. His image even appeared on a baseball card celebrating the Congressional game alongside Major League legend Willie Mays.

Afterward, Frey launched unsuccessful bids for the U.S. Senate and for governor, but never returned to elective office. Until his retirement in 2016, he was senior shareholder emeritus with the law firm Lowndes, Drosdick, Doster, Kantor & Reed.

Notably, Frey is considered a founding father of Orlando International Airport. He successfully appealed to President Richard M. Nixon to allow the City of Orlando to take over the former McCoy Air Force Base property and turn it into a commercial airfield. The price was only $1.

Frey’s legacy also includes ensuring that Kennedy Space Center became the home of the Space Shuttle, and the creation of Spessard Holland Seashore Park, now Canaveral National Seashore Park. He and Democratic U.S. Representative Bill Chappell co-sponsored legislation creating the park.

Although he practiced law for a living, Frey was never far removed from current events through his radio commentary, his books and his institute. He wrote and co-edited two books: Inside the House: Former Members Reveal How Congress Really Works (2001) and Political Rules of the Road: Representatives, Senators and Presidents Share Their Rules for Success in Congress, Politics, and Life (2009).

Frey, according to the institute, was “always a participant, never a spectator.” In his optimistic, inclusive leadership style, he set an example that will be forever relevant and remembered.

— Catherine Hinman