Researched By Kimberley Mould and Daena Creel

Photo Restoration By Will Setzer, Design7 Studios

Through the decades, various people of fame and fortune have called Winter Park home, contributing successively to the town’s wide reputation today as a canopied oasis of culture and fine living. They have been actresses and comedians, business executives and television personalities, poet laureates and NBA stars.

Perhaps the first in this distinguished list was Isabella Macdonald Alden, a Victorian literary celebrity known to her readers as “Pansy.” The world-renowned children’s writer moved with her husband and son to Winter Park in 1886, when developers Loring Chase and Oliver Chapman had barely completed platting the town and opening roads. Population was under 300.

Alden’s ornate three-story home at the corner of Interlachen and Lyman avenues, known as the “Pansy Cottage,” became a hub of local culture. Alden considered her family to be “Florida pioneers [who] located in the new little town of Winter Park as the most desirable town to build a home.”

Her husband, Presbyterian minister Gustavus Rossenberg Alden, became a trustee of Rollins College, and her son, Raymond, attended the college and went on to an illustrious academic career.

Alden, an educated woman with a missionary’s quiet zeal, possessed both the talent and skill to impart life lessons through her Christian books and stories. In this churchgoing era, she became an international publishing phenomenon — and the synergy of the media platforms in which her work appeared was positively Disneyesque.

She wrote hundreds of stories for both young children and young adults, edited dozens of compilations and penned more than 70 full-length novels — some translated into French, German, Russian and even Japanese. The books sold hundreds of thousands of copies, easily making her one of the genre’s most popular authors.

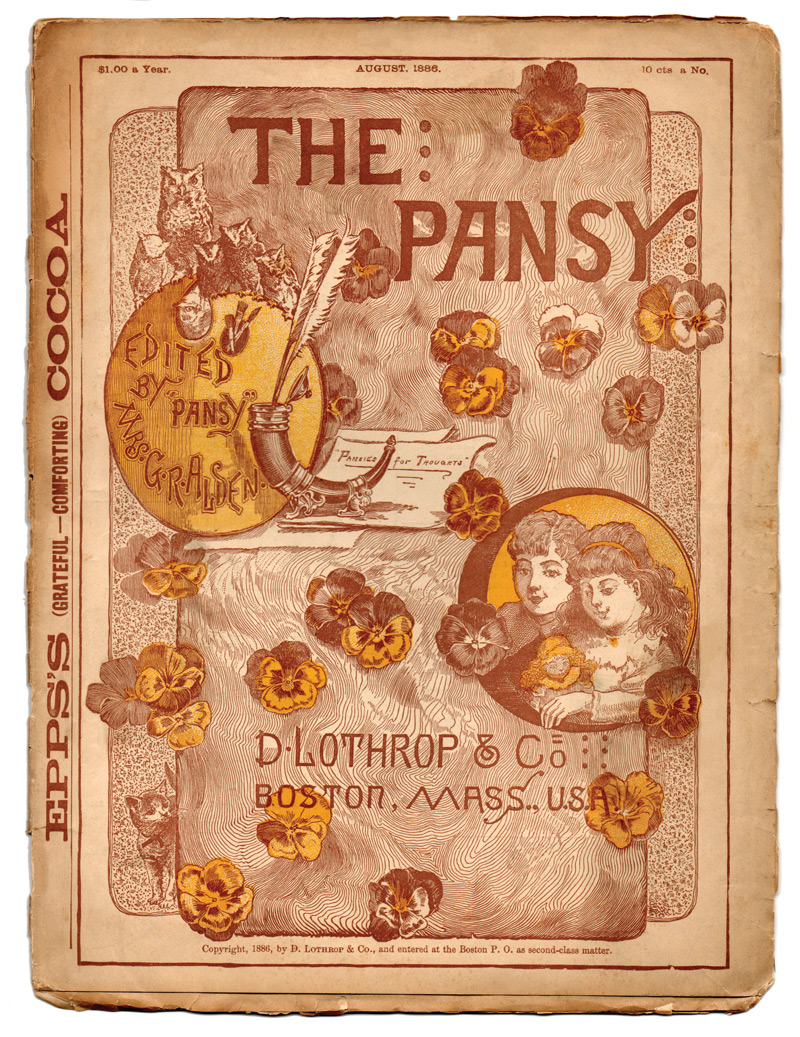

Alden also edited a widely circulated magazine for children called The Pansy. It featured her own serialized stories and those written by friends and family, as well as literature and educational articles on topics such as world history, geography, science, literature and botany. And her fiction was a favorite of Sunday-school teachers and church librarians.

She often said, “I dedicate my pen to the direct and continuous effort to win others for Christ and help others to closer fellowship with him.” At the height of her career, Alden received thousands of fan letters each week from her young readers and did her best to respond personally to as many as she could.

Children who subscribed to The Pansy could join the “Pansy Society,” which encouraged members to work hard at overcoming a single fault “For Jesus’ Sake.”

Alden produced Sunday school lessons for the Westminster Teacher, a publication of the Presbyterian Church, and wrote for or served on the editorial staff of periodicals such as Trained Motherhood, The Advance, The Interior and Herald and Presbyter — a weekly Presbyterian newspaper.

She contributed stories and was a regular columnist for two weekly youth papers, Christian Endeavor World and its counterpart, Junior Christian Endeavor World.

“She wove her stories around common, everyday [lives], until all her characters became alive and real to those who read,” wrote Grace Livingston Hill, Alden’s niece and a novelist whose first published book was written in Winter Park.

Alden even had her own board game, “Divided Wisdom: A Game Based on Hymns and Bible Proverbs.” She was included among other well-known writers in two editions of the “Authors” card game, too.

The author often endorsed the work of others, including Dr. Mary Wood-Allen, whose 1905 facts-of-life tome What A Young Girl Ought to Know she described as “just the book to teach what most people do not know how to teach, being scientific yet simple, and plain-spoken yet delicate.”

The so-called “Pansy Books” and their creator are all but forgotten now, except by dedicated bibliophiles who collect early editions for their rarity rather than their literary quality. Alden’s works were out of print for decades until a Christian publishing house released a handful of edited and abridged titles in the 1990s.

In 1981, Elizabeth Eschbach wrote in the Orange County Historical Quarterly: “Somewhat simplistically by today’s worldly sensibilities, Alden’s books emphasized the perils of popular amusements, the evils of worldly temptations, necessity of abstinence and self-sacrifice and the trials of leading a good Christian life.”

Nonetheless, there has been a resurgence of interest today, and a small-but-loyal following is growing on social media. Nearly all of Alden’s novels have been re-released as high-quality ebooks, ready for modern readers to discover.

If the Pansy books don’t hold up particularly well as literature, they do hearken back to a simpler time, both in the United States and in the quaint Central Florida town where the author and her family spent many of their happiest and most productive years.

Isabella Macdonald Alden was born November 3, 1841, in Rochester, New York. Her parents, Isaac and Myra Spafford Macdonald, instilled in their six children a commitment to moral and social reform. Late in life, Alden wrote that her father “in all his lifetime struggled with the handicap of a suffering body, and sometimes found it burdensome to meet the daily expenses of a large family.”

However, she added, “looking back, we all knew — and I, left here alone, the others having all reached home before me, know — that there could never have been a more faithful, conscientious, earnest, loving father and mother than God gave to us.”

Precocious Isabella began her schooling at home and showed an early propensity for writing. She recalled that as a child she “possessed a temper that was easily set aflame, and a will of my own that took careful training to educate.” Her father tasked her with keeping a daily journal. That routine not only helped to calm her stormy temper, it also set into motion her life’s work.

The youngster’s first published story, Our Old Clock, appeared in a Gloversville, New York, newspaper that her brother-in-law edited when she was just 10 years old. The byline read simply, “Pansy.”

The distinctive nom de plume, Alden recalled in her autobiography Memories of Yesterdays, “had to do with a certain tea party connected with my childhood.” Her mother wanted to rest before her guests arrived, and Isabella wanted to be helpful. Knowing that five or six pansies were to decorate each place setting, she went out to the garden and picked every one, pulling off the stems.

Her mother, who had planned on making pansy bouquets for her guests, scolded her daughter, and Isabella began to cry. Her father intervened. “Didn’t you hear her tell you to look in her apron and see what a lot of work she had saved you? Can’t you see how she thought it out?”

The outcome was this: “I was kissed and told that Mother did not believe I meant to be naughty. She washed my face and brushed my hair and dressed me herself in my best white dress… and my familiar home-name ‘Pansy’ dates from those stemless ones of the long ago.”

After those early days of home schooling, Isabella attended the Oneida Seminary in Oneida, New York. It was here that she met Theodosia Maria Toll Foster, charmingly nicknamed “Docia,”

Foster would become Isabella’s best friend, collaborator and ultimately go on to write more than 30 of her own books as “Faye Huntington.” After graduating from Oneida Seminary, Alden promptly joined the faculty in 1860 and, a few years later, taught in Auburn, New York.

It was Docia who, in 1864, helped start the Pansy phenomenon. She surreptitiously rescued and submitted a manuscript that her friend had written and then set aside, believing it to be unworthy.

Helen Lester had been written at Docia’s urging in response to a contest sponsored by the Cincinnati-based American Reform Tract and Book Society, which published and distributed evangelical materials. The organization was seeking the best children’s holiday gift book setting forth the principles of Christianity.

In her autobiography, Alden recalls telling Docia, in no uncertain terms, that her decision to abandon the story was final. “If I can’t write a better story than that, it proves I ought never to write at all,” she said. “Tear the thing into bits and throw it into the grate with the other rubbish. I’ll set fire to them tonight.”

Docia, who told her friend that she was “acting like a born idiot,” then appeared to drop the subject. Two months later, however, Alden received a $50 check and notification that her story had won first prize.

Chastened but delighted, Alden later recalled her reaction: “Shall I make an attempt at describing the hour of bewilderment, amazement, embarrassment, oddly mingled with delight, which followed the first reading of that letter?”

Alden sent autographed copies of Helen Lester — and the prize money — to her parents. One of these rare copies of Helen Lester resides in the archives at Rollins College’s Olin Library, signed in her own hand, “A birthday gift to my dear father from his daughter Pansy.”

In the story, Helen, known as “Nellie,” is a darling but imperfect child whose once-wayward older brother, Cleveland, undergoes a religious conversion that he is eager to share with his siblings and his wealthy, worldly parents.

For example, while headed home from a prayer meeting that has stirred his little sister, Cleveland says: “Oh, Nellie, I want you to be a Christian. I don’t want you to grow up without loving this dear Savior who loves you so much. I want you to learn to pray; to learn to ask Jesus every day to take care of you; to help you to love him more than anybody else.”

Shortly after Helen Lester appeared, the young author met her future husband over a piece of her Thanksgiving pumpkin pie. She was living at Auburn Theological Seminary with her sister and brother-in-law, Charles Livingston, who was studying for the ministry.

After their holiday dinner, Charles took a walk to see if there were any lonely students about campus and returned with Gustavus Rossenberg Alden.

The couple married in 1866 and moved to Almond, New York, where Reverend Alden pastored a church. Other assignments would take them to Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C. As she assisted her husband in his work, Alden found constant inspiration. “Whenever things went wrong,” she recalled, “I went home and wrote a book to make them come out right.”

Alden seemed to truly find her niche after the publication in 1870 of Ester Ried: Asleep and Awake. Ester, who toils grudgingly at her family’s New York boardinghouse, believes herself to be “a Christian in name only” until she visits a cousin, Abbie, who teaches her to base her life on God’s word.

The book begat a series featuring the same character and her relatives, with the final installment published in 1906. Like Helen before her, Ester comes to realize that carefully reading the Bible and following its precepts is the only prescription for her attitude problem.

“That is what has been the trouble with me,” Ester tells herself. “I’ve neglected my duty…well, the first opportunity then that I have — or no — I’ll stop now, this minute, and read a chapter in the Bible and pray; there is nothing like the present moment for keeping a good resolution.”

The Herald and Presbyter magazine, owned by Monfort & Company, serialized many of Alden’s book-length stories, including Ester Reid and several of its sequels, then published them in book form.

In 1874, Alden and Monfort founded The Pansy, a monthly magazine that cost just 25 cents a year. As the magazine and its readership grew, it was described as “a finely illustrated monthly, containing 35 to 40 pages of reading matter from the pens of the best writers especially prepared for the boys and girls of the world.”

The editor was identified only as “Pansy,” but by then that name was well-known in the world of children’s Sunday-school literature. By the end of its first year, The Pansy had more than 20,000 subscribers and would be published for another 21 years.

Alden’s productivity was all the more remarkable given that she suffered from severe migraines and could work only a few hours each day. Mornings were her sacred time for writing, and between the rapid clicks of the typewriter and sharp ring of its bell, there was “scarcely a pause for thought,” according to her niece, Grace.

“Much of her thinking is done when going about her house attending to small duties, making her bed, or putting to rights a room,” Grace wrote in an April 21, 1892, article called “Pansy at Home” for The Golden Rule magazine. “When she sits down to write, her thoughts are drilled like a well-ordered army, ready to march at the word.”

On March 30, 1873, in New Hartford, New York, the Aldens’ only son was born. As a child, Raymond Macdonald Alden suffered with frail health and doctors advised a move south to a warmer climate.

The family decided to join Alden’s sister, Marcia Macdonald Livingston, and brother-in-law, Reverend Charles Montgomery Livingston, in Winter Park in 1886. In late 1885, Reverend Livingston had been called as a Presbyterian “Home Missions Pastor” to Seneca and Sorrento churches in Lake County.

The Pansy Cottage was completed in the fall of 1888, although the term “cottage” was a bit of a misnomer for the Alden home. A lavish, three-story Victorian masterpiece built from virgin pine, it was replete with verandas, turrets and every architectural flavor of gingerbread. Almost every room had a fireplace.

The Aldens lived in Winter Park until 1891. The Alden house, which eventually became the Interlachen Inn, survived as a local landmark until 1955. Winter Park promoters eagerly touted the fact that one of the country’s most popular authors, who could have lived anywhere, had selected “the bright New England town on the Florida frontier.”

An 1888 brochure listed Alden among the literary luminaries who called Winter Park home and described Pansy Cottage as “a center of literary, religious and civic activity.”

The Aldens became involved in a variety of community betterment causes. Reverend Alden was elected to the Rollins board of trustees, and the family helped found the Winter Park Public Library and the local chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

The WCTU was one of Alden’s favorite organizations. Although abstinence is a long-lost cause, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, per-capita alcohol consumption was far higher than it is today and was blamed for such problems as spousal abuse and child abandonment.

Alden had been deeply affected by an event in her childhood in which a baby from a family she had known suffered permanent brain damage after being kicked by a drunken father. The temperance theme appears throughout many of her books. Notably, the WCTU was involved in such social issues as suffrage and public health.

The Aldens joined the city’s First Congregational Church, which had founded Rollins in 1885 and attracted a socially prominent congregation. Raymond began his studies in the college’s Preparatory Department but eventually transferred to Columbian University (now George Washington University) in Washington, D.C. He also studied at Harvard and at the University of Pennsylvania, where he earned a Ph.D. in English in 1898.

In an early Rollins promotional pamphlet, Reverend Alden is quoted saying, “My son went to Florida as an invalid, by the advice of his physician; he left with health fully restored.” Raymond taught English at Penn as well as Columbia, Harvard and Stanford.

He would later chair the English department at the University of Illinois and become one of the world’s preeminent scholars of Shakespeare. He would be awarded an honorary degree in literature from Rollins in 1910.

Alden used the influence she had to herald Rollins. In the August 1888 issue of The Pansy, she wrote an entire column about the college, imploring her “many thousand helpers” to “tell every Northern friend you have that in Winter Park, Orange County, Florida, is a college; … a real honest, well-built well-managed college with four good buildings.”

Alden frequently used envelopes advertising Rollins to respond to letters from her readers.

Alden had a long association with the organization that became the prestigious Chautauqua Institution in New York. The grassroots adult-education movement was named for the lake where its first meetings were held. Though Chautauqua expanded in time to include secular topics, it had its origins in 1874 as a summer assembly of Sunday School teachers.

Alden and her family spent summers either at Chautauqua or traveling to various Sunday School assemblies or regional Chautauquas as speakers. One of her series of books, The Chautauqua Girls, is based on summer days spent at those meetings.

Chautauqua meetings were initially held only at the New York compound, but eventually there were large-scale gatherings throughout the country spotlighting speakers, teachers, musicians, entertainers, preachers and subject-matter experts.

In fact, Reverend and Mrs. Alden and their niece, Grace, were frequently a part of the Florida Chautauqua meetings, including those at Mount Dora and DeFuniak Springs. Eventually, a “Pansy Cottage” was built in DeFuniak Springs, too.

By 1891, the Aldens’ time in Winter Park had come to an end. On December 5, the local paper reported that “Rev. G. R. Alden is in town looking after his Winter Park interests and sending some of his belongings to his new home in Washington, D.C. His change of residence reminds one of the familiar saying: ‘Another good man gone wrong.’”

The family moved to Washington, D.C., to accept the call to a church there while Raymond studied at Columbian University. The books continued, however, including Four Mothers at Chautauqua and the final installment of the Ester Ried series.

In 1924, at the age of 83, Alden suffered the loss of her husband, her sister, Marcia, and her son, whose deaths were separated by only six months. Distraught, she moved to Palo Alto, California, to live with her daughter-in-law and five grandchildren.

A concerned Hill suggested that Alden might want to revisit Ester Ried, but Alden demurred. “I am not capable of writing a story suited to the tastes of present-day young people,” she wrote. “They would smoke a cigarette over the first chapter and toss it aside as a back number. I haven’t faith in them, nor in my ability to help them.”

Jean Kerr, whose biography of Hill describes Alden’s final days, wrote: “Lonely for those who had gone before her and saddened by the godless trends of the modern world, she found her escape in her memories of the golden days that were past: memories of school-mates, of family gatherings, of the old Chautauqua assemblies, of satisfying work and pleasant associations.”

Disillusioned but unwilling to cap her pen for a final time, Alden began work on her autobiography. Memories of Yesterdays was incomplete when she died on Aug. 5, 1930, at the age of 89. Her beloved niece, Grace, finished the book.

Although her passing received national coverage, she had lived longer than her audience. One critic wrote: “Isabella Alden has suffered the fate of all those who survive beyond their own day and attract attention only as anachronisms on the modern scene.”

A piece published in the St. Louis Star was more kind: “But what’s the use of judging this once popular author by modern tastes and standards? … Were their efforts wasted? We don’t believe it. Nobody need be too sure that the present generation wouldn’t be better off if once in a while it sat down with a Pansy book in its hands…”

Isabella Macdonald Alden made the news again in December 1993 when Winter Park City Commissioner Rachel Murrah was shopping on Park Avenue for a red holiday coat and noticed a book in Talbots’ display window. The book, which was meant purely for decoration, was an early edition of Esther Ried: Asleep and Awake. Recognizing the author’s name, Murrah persuaded the store to donate it to the Winter Park Public Library.

“What do you call this? Serendipity?” said Renae Bennett, then the library’s historian, in an interview with the Orlando Sentinel. “We’re thrilled.”

The items on display in the Winter Park Talbots, like those in the 339 other Talbots across the country, had been bought in lots from antique dealers through the company’s Boston headquarters. The fact that a Pansy Book ended up in its Winter Park store was an extraordinary coincidence and a reminder: Pansy, after all, still has something to say.

Amazing Grace

Pansy’s niece combined romance and piety in her own best-sellers.

Isabella “Pansy” Alden was already a household name across the U.S. when she arrived in Winter Park. But it was here that her niece, Grace Livingston Hill, took the first steps in becoming her Auntie Belle’s literary legacy.

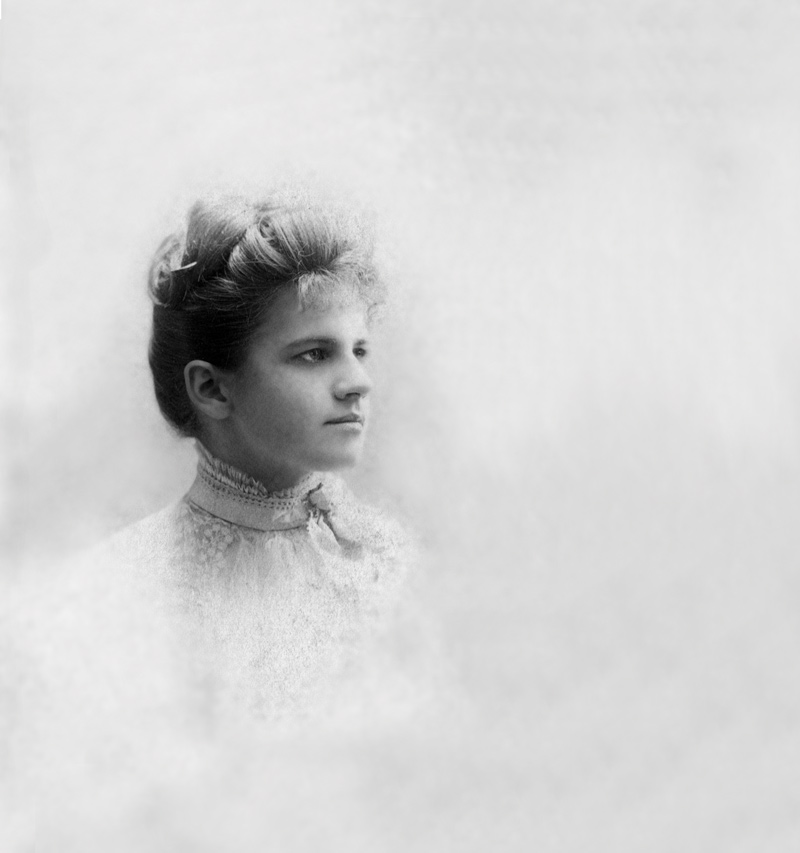

Grace, whose fame as a novelist would eventually eclipse Isabella’s, came to Winter Park in 1885 at age 20 with her parents, Reverend C.M. Livingston and Marcia Macdonald Livingston, who was Isabella’s sister.

Afflicted with a respiratory condition, Grace’s father had been given a leave of absence from his pastorate in Campbell, New York, to see if a “more congenial climate” could restore his health.

The Livingstons subsequently encouraged Isabella and her husband, Rev. G.R. Alden, to join them in Winter Park, where their invalid son, Raymond, could grow stronger — and they had made a happy home.

The two families spent a great deal of time together, working in what might be called the family business. Everyone — including Grace and young Raymond — wrote stories or regular columns for Isabella’s children’s magazine, The Pansy.

Loring Chase, one of the founders of Winter Park, noted that “literary merit seems to belong to almost every member of the family, and thousands have been delighted with the pen pictures of not only Dr. Alden and Pansy, but of Reverend and Mrs. Livingston, Miss Grace Livingston and Raymond Alden. They all work industriously to give to the youth of our land good moral reading, as the excellent reputation of their writings attest.”

Grace adored her aunt. “As long ago as I can remember, there was always a radiant being who was next to my mother and father in my heart, and who seemed to be a sort of combination of fairy godmother and saint,” she wrote years later.

Isabella, wrote Grace, was “beautiful, wise and wonderful; I treasured her smiles, copied her ways and breathlessly listened to all she had to say, sitting at her feet worshipfully.”

Her aunt’s financial success no doubt also made an impression on Grace. In the late 19th century, society viewed the arts as a respectable vocation for women. Hill wanted to earn money to help her family travel.

The move to Florida did wonders for Reverend Livingston’s throat, but Grace, restless, longed for summers in New York on the shore of Chautauqua Lake, where she grew up attending the popular camp meetings that combined religious instruction with cultural and literary offerings.

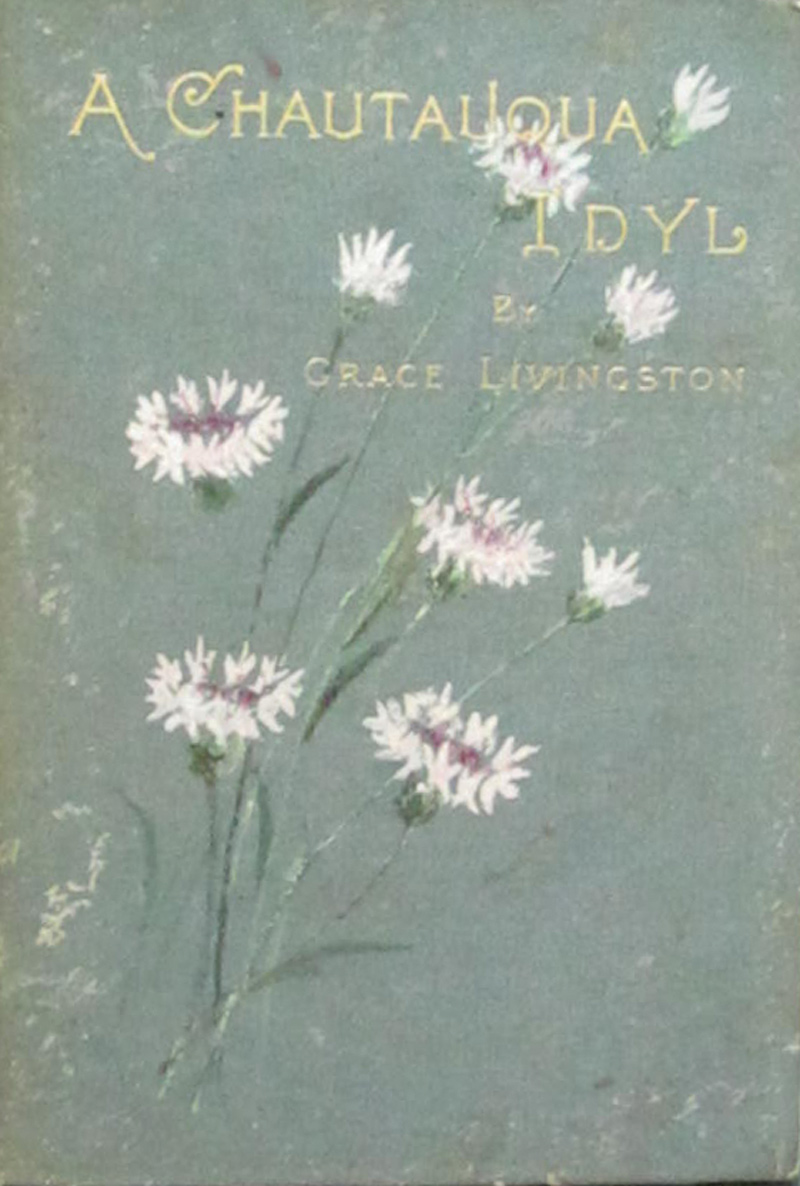

The meager salary of a home missions pastor made a trip north prohibitive. Looking to her aunt as a role model, it only seemed natural that Grace, too, could publish a novel. For its subject, she chose her beloved Chautauqua.

A Chautauqua Idyl tells the story of “the birds and the trees and the running brooks” deciding to have their own Chautauqua-style meetings. The unique imagery and simplicity of Grace’s writing caught the attention of her aunt’s publisher, and once the contract was signed, there was enough money available for the Livingstons to make the journey. The book was published in 1887.

Grace would publish several more volumes during her years in Winter Park. A daily devotional called Pansies for Thoughts combined passages from her aunt’s “Pansy Books” with Scripture verses for each day of the year.

She also wrote a children’s book, A Little Servant, and contributed chapters to two family efforts: A Sevenfold Trouble and The Kaleidoscope, which included a chapter contributed by a Rollins professor and would-be but ultimately unsuccessful suitor, Dr. Frederick Starr.

Grace herself was sought out by Rollins College, but not for her gifts with the English language. Admired for her athleticism, she was asked in 1889 to join the faculty as an instructor in calisthenics and heavy gymnastics — at no salary.

She readily accepted, later writing that “the days spent in Winter Park with the dear Rollins students will ever stand out as a sweet and delightful experience.”

The new Lyman Gymnasium, where her classes were held, was an attraction unto itself. But Grace’s sessions also began to draw large crowds of spectators. According to the Florida Times-Union, “the system of calisthenics and gymnastics…is very pretty, and from 5 o’clock each afternoon the guests’ galleries are thronged with a delighted audience.”

It’s no wonder the galleries were full. Rollins was one of the few places in the 1890s where a woman instructor led vigorous physical education classes, including “club swinging, fencing, free work, wand, dumb-bell and hoop exercises.” One of the most notable and entertaining was “Greek posing” for young men and women.

Reverend and Mrs. Livingston left Florida in 1892 after receiving a call to pastor a Maryland church. Grace went with them and a few months later married Rev. T.G.F. Hill. It was as Grace Livingston Hill that she would become familiar to generations of readers.

But there’s no doubt that Grace kept Winter Park close to her heart, and in her writing, she sometimes hearkened back to her Florida sojourn. If there is a “dear old aunt” in a Grace Livingston Hill book, she, who usually wore “becoming shades of gray,” is almost always based on Pansy.

Among Grace’s books with Florida settings, two stand out.

The Story of a Whim (1903), a gentle romance, appeared first as a serial in The Golden Rule magazine. Its setting among the orange groves in fictional Pine Ridge, Florida, was no doubt inspired by the fact that her uncle, Reverend Alden, owned 12 acres of citrus between Winter Park and Maitland. The town near the groves was modeled after Sorrento, where the church building at which Reverend Livingston pastored still stands and holds services today.

In Lo, Michael (1913), Rollins itself serves as the backdrop. As the book opens, an angry mob is gathered outside the Manhattan home of Delevan Endicott, president of a failed bank. A shot rings out and a newsboy, nicknamed Mikky, throws himself in the bullet’s path to save the life of Endicott’s young daughter, Starr.

In gratitude, Endicott sends the unpolished but angelic lad to a small school in Florida, unnamed in the book but clearly based on Rollins.

Years later, Endicott and Starr travel to the college town for a visit. Grace’s memory of Winter Park’s early days is sprinkled throughout the narrative, and readers can almost see the Dinky Line station in the twilight or Rogers House (Winter Park’s first hotel, today the site of The Cloisters condominiums.) across the way:

Starr, as she walked on the inside of the board sidewalk and looked down at the small pink and white and crimson pea blossoms growing broad-cast, and then up at the tallness of the great pines, felt a kind of awe stealing upon her. But here in this quiet spot, where the tiny station, the post office, the grocery and a few scattered dwellings with the lights of the great tourists’ hotel gleaming in the distance, seemed all there was of human habitation; and where the sky was wide and even to bewilderment; she seemed suddenly to realize the difference from New York.

Now an enthusiastic and exemplary student, Mikky gives his benefactor and his pretty daughter a tour of the campus — and modern readers a glimpse at Rollins life over a century ago:

“That’s the chapel, and beyond are the study and recitation rooms. The next is the dining hall and servant’s quarters, and over on that side of the campus is our dormitory. My window looks down on the lake. Every morning I go before breakfast for a swim.”

Finally, he shares a Florida sunset with the girl he saved so long ago:

Starr followed his eager words, and saw the sun slipping, slipping like a great ruby disc behind the fringe of palm and pine and oak that bordered the little lake below the campus; saw the wild bird dart from the thicket into the clear amber of the sky above, utter its sweet weird call, and drop again into the fine brown shadows of the living picture; watched, fascinated as the sun slipped lower, lower, to the half now, and now less than half. Breathless they both stood … and watched the wonder of the day turn into night.

Grace’s charmed life took a tragic turn in 1899, when her husband died suddenly after just seven years of marriage. Her father died just a few months later. With her mother and two daughters, ages 2 and 6, to support, she took a cue from her aunt and redoubled her effort at writing.

In less than a decade, despite a failed second marriage to Flavious Josephus Lutz, a church organist 15 years her junior, she was a best-selling author with a lifetime contract from J.B. Lippincott Co.

Her protagonists were most often young Christian women or those who converted to Christianity during the course of the story. Grace’s ability to appeal to secular audiences by combining romantic themes with an ever-present gospel message was key to her ongoing popularity.

New Grace Livingston Hill books appeared three times a year for much of her career and have never been out of print. Prior to the advent of talkies, three were adapted as films. She ultimately wrote more than 100 novels and dozens more short stories, with book sales steadily approaching the 100 million mark today.

Grace died in 1947 at 82. Her final book, Mary Arden, was completed by her daughter, Ruth Livingston Hill Munce, a St. Petersburg resident who founded The Grace Livingston Memorial School in1953, today the Keswick Christian School.

Outside of the Christian realm, Grace’s books never received much critical praise. Many called them “formula” or “fluff” or even “out-and-out escapism.” But as with her aunt, who viewed her work as a calling, that never bothered Grace:

“I have had no desire to find favor with critics. I knew my Lord could look after these things wherever He wanted my work to reach lost souls.”

A Matter of Dress, or Undress, at Rollins

As a popular young physical education instructor at Rollins College in its nascent years, future novelist Grace Livingston had some thoroughly modern ideas. At least one caused the old guard alarm.

In a letter to the college four decades later, she recalled an 1891 incident that she considered to be “exceedingly amusing in the light of present-day freedom and daring in the matter of dress, or rather undress.”

She wanted her female students to wear uniforms. She suggested dark blue serge suits with long-sleeved, sailor-collared blouses. The controversy arose over the “divided skirt” — think culottes — which would be fastened just below the knee. Grace described them as “very neat and graceful, worn with long black stockings and gymnasium sneakers.”

It was hardly a revolutionary concept. At the time, many girls who participated in athletics of one kind or another, primarily riding, wore split skirts, which allowed for greater freedom of movement while preserving modesty.

“I was to appear formally before the faculty to talk over the matter of costume for the gymnasium work, and it never occurred to me that it was going to be a difficult task to get what I had requested,” Grace wrote.

After all, she had “been brought up in a most conservative manner as to attire, and I was heartily in accord with my father and mother on the subject. So I was much amazed to find that all but two or three of the faculty were very doubtful and failed to give way at my eager description of its modesty and appropriateness.”

Grace “waxed eloquent” about the proposal, noting that the gym uniforms were, in fact, more conservative than much of what her students donned outside of class.

Seeing that her arguments were making little headway, she shocked the prim professors by making an audacious offer: “Why, I have it on now and I can show it to you. I’ll step into the hall and take off this skirt and come back and let you see how it looks.”

One of the female teachers “tried to protest, but I whisked into the hall before they could stop me and walked back in my gymnasium dress, and in reality, it was a pretty graceful affair. Even now it might be thought so. But the affect [sic] on the troubled faculty was astounding.”

Grace watched as the attendees “sat in a circle with downcast eyes, hands in their laps, feeling perhaps that a great crisis in college affairs was upon them. Only the two brave ladies who had been privileged to see the skirt before, and were in hearty accord with me about it, looked up with serene countenances and smiled upon me.”

The others, she recalled, began to cast “furtive sideways glances, first at my toes, and then cautiously letting their frightened eyes travel upward till they got the whole effect. They one by one drew sighs of relief and permitted their eyes to resume a normal outlook on the world once more.”

Dr. Edward Hooker, the college’s first president and minister of the First Congregational Church of Winter Park, finally broke the awkward silence. “I think,” he said, “that this dress is much more modest than the garb that is worn in social life. I can see nothing whatever objectionable in it. In fact, I heartily approve it.”

Thus ended the “great crisis,” and soon thereafter girls could be seen hurrying across the campus wearing the sensible, graceful garb. “Nobody thought any more about it,” Grace wrote.