The sixtysomething man who answered the door at his subur–ban Winter Park home — barefoot, balding, moon-faced with a fringy white beard, baggy algae-green shorts, a blousy Route 66-themed shirt tenting a modest paunch — would never be mistaken for “The Most Interesting Man in the World.”

Instead of the daring dandy in those ubiquitous Dos Equis beer commercials, Edward Meyer looks to me like a guy waiting in line at the DMV. A regular Joe named Ed. But for 33 years, Meyer held arguably The Most Interesting Job in the World — believe it, or not!

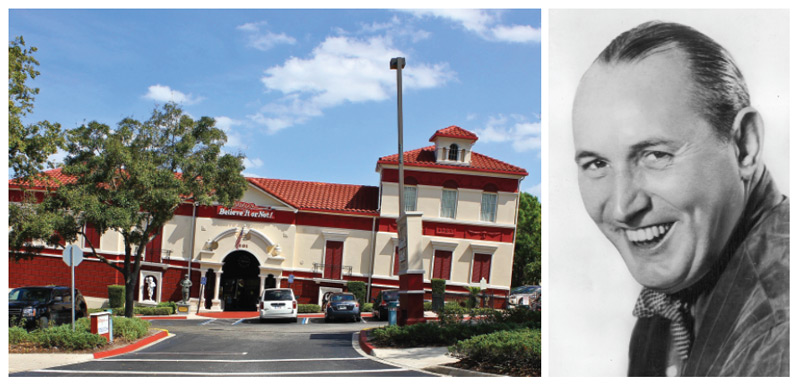

In fact, that’s exactly where Meyer worked. Ripley Entertainment Inc., a division of the Jim Pattison Group, is a global company with annual attendance of more than 12 million in 30-plus museums (the company calls them “odditoriums”), including the delightfully dizzying off-kilter building on International Drive in Orlando.

As vice president of archives and exhibits for the Ripley empire — which also includes books, games and a syndicated television show — Meyer visited six continents, 42 countries and 47 states.

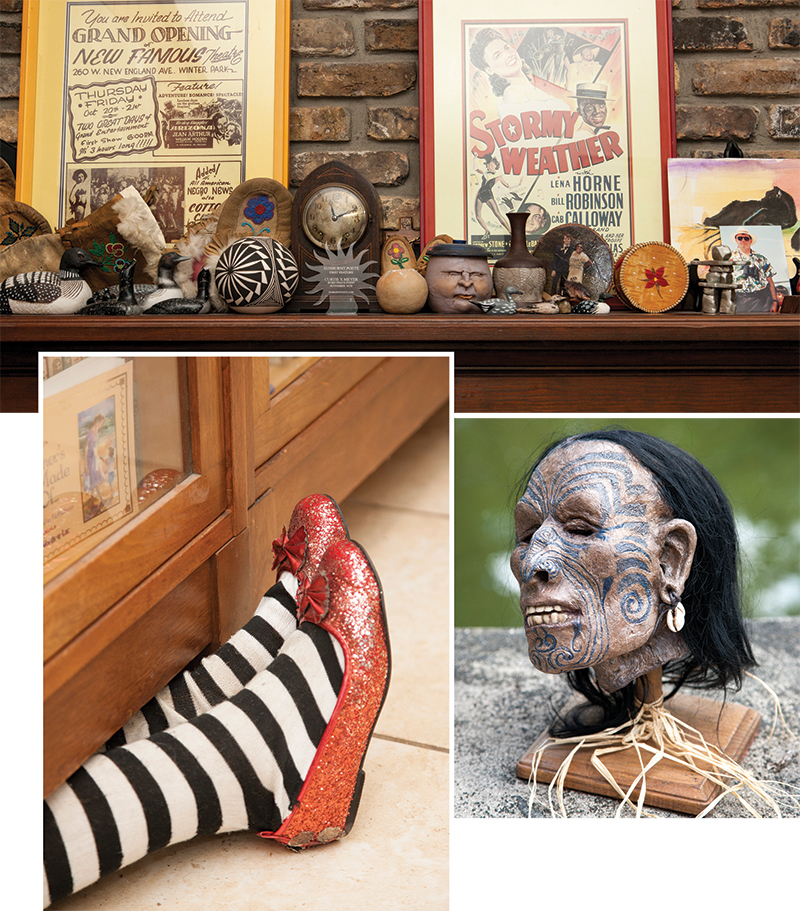

And he came back with intriguing, grotesque, disturbing, awesome, revolting and, yes, often unbelievable objects — from shrunken heads and conjoined farm animals to a portrait of Abraham Lincoln in Duct tape and a bovine hairball the size of large grapefruit.

I ask a question Meyer has probably answered many times before. Is “Believe It or Not” a boast, or is the “or Not” a caveat meant to provide wiggle room on authenticity?

“It’s a boast,” Meyer insists. “We would not put our name on it unless we were 100 percent convinced it was real. These things are so weird, we know you’re going to have doubts. But despite the title, you should believe it.”

Meyer, 63, retired in June of last year due partly to festering friction among Ripley executives over his paying $5 million at auction in 2016 for the dress Marilyn Monroe wore to croon “Happy Birthday” to President John F. Kennedy at Madison Square Garden in 1962. The company owner had OK’d the purchase, Meyer says, but other higher-ups begged to differ, and he was uncomfortable in the crossfire.

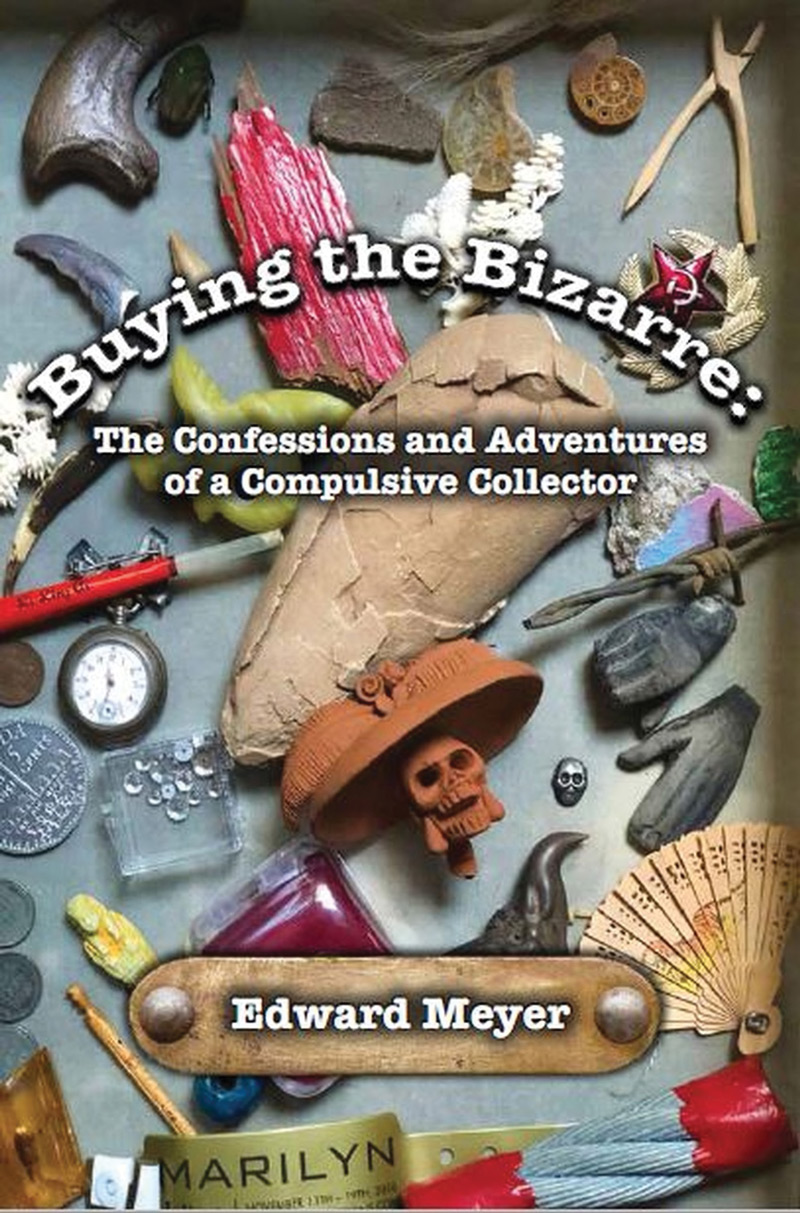

L’affaire de dress is recounted in minute and colorful detail in Meyer’s memoir, Buying the Bizarre: Confessions of a Compulsive Collector, published in May. But such are the staggering volume and variety of his Ripley adventures that the story of what Meyer calls “the most significant pop culture piece in history” doesn’t appear until chapter 74 of the 547-page saga.

“I’m the guy who spent over five million dollars on a dress that didn’t even fit me,” Meyer writes with wry, self-deprecating humor that marks his storytelling.

In a fond farewell to Meyer on the Ripley’s website, the company credits him with acquiring well over 500 artifacts a year for 33 years, which equals, at a minimum, 16,500 objects.

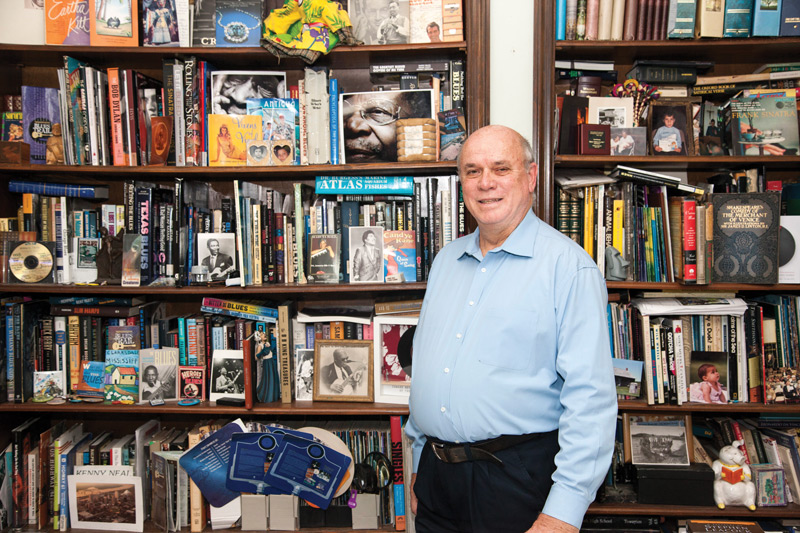

At first glance, it appears that all 16,500 are stored in his home. Seated in a beaded African throne at the table where he does his writing on a laptop, Meyer scans the expansive family room in which every inch of wall and shelf space is taken.

“My house is a disaster area,” Meyer says, noting a half-complete renovation awaiting an MIA contractor. “My desk was a disaster area, but I know where everything is. There’s an organizational thing in here that most people couldn’t comprehend by seeing it. I never liked to put things away, because I was sure I was going to need them. I liked to have as much as possible within reach.”

In his book, Meyer insists that his home is not a museum despite “six chock-full glass display cases, African statuary, tribal masks, exotic rugs including a full-length Tibetan tiger rug made from yak hair, a vial of dust from a Martian meteorite, a few old valuable coins and stamps, over 200 framed pieces of art … and an antique map of Iceland.”

Deep breath.

And then there’s the personal stuff: a pocket watch collection, a bookshelf shrine to baseball and 13 racks containing thousands of record albums and CDs. Meyer recently put the finishing touches on the manuscript of his second book, A Man and the Blues: A Love Story, an ode to his passion for African-American blues.

Then there are more than a dozen large bookshelves “filled with everything I’ve ever read, and then some.”

CHAMPS AND CHUMPS

Meyer grew up in Toronto reading the Believe It or Not! cartoon panel, which debuted in 1918 in The New York Globe under the name Champs and Chumps and featured oddities from the world of athletics — not surprising, since the 28-year-old creator Robert Ripley had been a sportswriter.

Ripley began adding non-sports items to the column and a year later settled on Believe It or Not!, the cornerstone of an entertainment empire. Catnip though Believe It or Not! was to a young boy’s brain, the cartoon did not inspire Meyer to make Ripley’s wacky wonderland his career. And why would it? Few read Believe It or Not! and think “job opportunity!”

Meyer’s career goal was grounded in deeply mundane reality — an orderly, hushed utterly believable universe. He wanted to be a librarian. “Most people wouldn’t believe it,” he says. “My high school teachers thought I was crazy. ‘What do you mean, you want to be a librarian?’”

What’s unbelievable is that nearly everything about Meyer’s early years, including the nerdy ambition, appears to have been uncanny preparation for his future job as buyer of the bizarre for Ripley’s. “I believe that 100 percent,” he says. “I thought about it a lot writing the book.”

Meyer’s mother, Sylvia, imbued him with a love of books and an omnivorous hunger for knowledge — birds, flowers, insects, trees, mummies, history, poetry, dinosaurs. He and his sister were expected to check out three books a week from the library.

“At the time, travel wasn’t all that available to me,” Meyer recalls. “Armchair travel, that’s really what it was all about. There was a librarian in grade school, Mrs. Taffe, that really put that in my head — that there’s a world in this building at your fingertips.”

Visiting exotic locales wasn’t in the family budget, but Canada afforded frequent low-cost road trips — camping only, no motels — that gave Meyer a Ripleyesque taste for the awesome, weird and tacky.

“We did things that other families didn’t do,” he says. “We went to unusual places and I absorbed it all.” At a roadside nature attraction, they fed a chained bear a blueberry pie. At a trading post in Banff, Alberta, they were mesmerized by a Fiji Island mermaid. They visited forts, graveyards, museums, monuments and welcome centers.

Still, all the fateful basic training for an unbelievable career with the oddball empire might have gone for naught but for a serendipitous moment that pointed Meyer to his destination.

It was spring 1978, and Meyer had just completed the final exam for his undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto with plans to enroll in the graduate library science program in the fall. In the meantime, he needed a summer job.

After dozens of fruitless visits, he had all but given up on the campus office for student employment. But a friend insisted that he give it one final try and dragged him through the doorway. Once inside, sunlight through a window appeared to illuminate an innocuous 5-by-5 card tacked to a bulletin board. The card read: “Wanted: Library Science Student to catalog cartoons for Ripley International, 10 Price Street, Downtown, Toronto.”

Meyer could scarcely believe his good fortune. “I loved cataloging, as I assume most would-be librarians do, and I loved cartoons,” he recalls. “So, it sounded like the perfect job.” The world lost a librarian but Believe It or Not! gained a successor to Robert Ripley, who was the company’s first and only buyer until his death in 1949.

Since Ripley’s untimely passing, the company had acquired only 74 new items. But in 1985, Meyer was promoted from archivist to hunter-buyer of exhibits. At the time, he recalls, there were eight Ripley museums containing only artifacts snared by Ripley himself.

The new owner, Jim Pattison Sr., wanted to build more museums. And Pattison, one of Canada’s wealthiest men, had the resources to do as he wished. His net worth in 2018 was estimated to be some $5.7 billion, and his company included such diversified holdings as truck dealerships, radio and television stations and the Guinness Book of World Records.

“We probably had enough [objects] to build two more museums at most,” Meyer recalls. “[Pattison] said, ‘That’s not good enough — I want to build two a year. Somebody has to go buy more stuff.’ My job changed overnight.”

SKIN IN THE GAME

During his first year, Meyer bought 485 objects. The most significant, he says, was a small patch of skin from a young Englishman who had murdered his teenaged lover in the 1700s by striking her with a flung rock. He was hanged then dissected in hopes of discovering the source of his evil.

The skin, which Meyer purchased for $300, was signed by the doctor who performed the dissection. “It’s just a tiny piece,” he says, “but if you ever see it, you’ll remember it.”

I’ll just bet. That’s true, for me, of the archetypal Ripley object: the shrunken head. It’s creepier and more unsettling than the iconic two-headed calf or “Mike” the headless rooster that toured sideshows for 18 years because, well, they’re farm animals.

The downsized human head — such as the one from Ecuador at the Orlando odditorium — hits a bit too close to home. There, but for the grace of God, goes my own deflated noggin.

“A lot people assume it’s not real,” Meyer says. “And almost universally no one understands how it can be done. It’s very simple. You remove the skull. You cannot shrink bone, but you can shrink skin because it’s basically just leather.”

To convince skeptics, Meyer made a film, a vivid re-enactment of the head-shrinking process for the exhibit. Let’s just say it’s not a popcorn movie. It did convince me — not to visit Ecuador anytime soon.

“I hope you liked the film,” he says. “I spent a lot of time making it. I bought the heads shown in it. The head in the Orlando museum is the best one in the company.”

(In 33 years of transporting unsettling objects, Meyer was stopped only once by airport security. “I had trouble getting into Ireland because I had a shrunken head in my suitcase,” he recalls. “They had never dealt with that before, so it was an interesting day.”)

Marilyn Monroe had been an object of fascination for Meyer since his teens. “I was spellbound by her beauty and sensuality,” he writes in his memoir. He was just the man to do Ripley’s bidding when the dress came up for auction in 1999 at legendary Christie’s Auction House in New York.

But he lost out that day. The “hammer price” was $1.1 million, topping Meyer’s final bid of $1 million. He came home with consolation prizes from the Monroe collection including a sweater ($150,000), a traveling makeup case ($240,000) and six snapshots of Monroe’s dog, “Maf” (short for Mafia), a gift from Frank Sinatra ($200,000).

Meyer wasn’t going to miss again when the dress hit the auction block in 2016 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills. Confident that he had Pattison’s support, Meyer kept raising his paddle until the hammer came down on his bid of $4 million. Julien’s 22 percent commission and taxes pushed the price tag to $5 million, the most by far Ripley’s had ever paid for an artifact.

Quibbling and second-guessing in the executive suite ensued. “I’m in the middle,” Meyer says. “My life became not as pleasant as it should be for a full year afterwards. It’s not the only reason I retired, but it was a big part of it.”

Ironically, one of Meyer’s proudest acquisitions didn’t cost Ripley a dime. That’s fortunate, since packing and shipping was a bear. Have you ever priced shipping a large quantity of concrete overseas? I’m guessing not. Meyer, however, has.

Three days after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, Meyer rushed to Germany with an empty suitcase and a hammer and chisel in hopes of bringing back some literal pieces of history. The suitcase proved inadequate for the 10-by-10-foot sections of wall he secured, 16 slabs adorned by the most artful spray painting. (One of the sections is on display at the Orlando odditorium.)

The addition met with resistance from some people, Meyer says: “More than once we were chastised, ‘Why is this in Ripley’s? It belongs somewhere else.’ There are no rules to what goes in a Ripley’s museum other than it’s unique. I felt I was preserving history.”

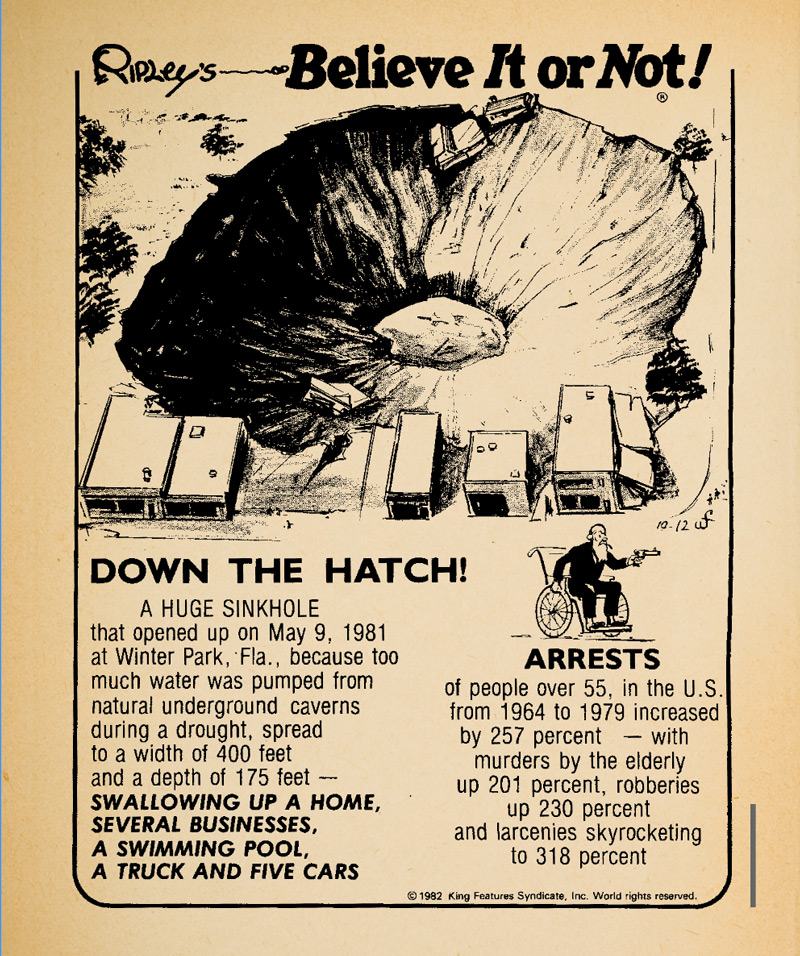

Speaking of the Orlando odditorium, which was built in 1992, it was Meyer’s stroke of genius to suggest a design that makes it appear the building is sliding into a sinkhole. His inspiration came from a Ripley cartoon featuring the Winter Park sinkhole of 1981. The cartoon ran long before there was any thought of an Orlando odditorium.

In 1993, a year after the I-Drive opening, Ripley moved its corporate headquarters from Toronto to Orlando. “The reason we looked at Orlando is that it already had Disney,” says Meyer. “Not a whole lot else, but it had Disney. We thought: ‘This is an entertainment city. Our company can grow there.’ For the company, it was a very, very good decision instantly.”

Orlando and Ripley did indeed seem to be a marriage made in pop-culture heaven. Yet, it almost didn’t happen. Meyer was on the five-person search committee scouting possible new locations.

“We were very seriously looking at Los Angeles,” he says. “We were literally on the ground in Los Angeles the day of the Rodney King episode, and that changed our mind on Los Angeles.” King was the construction worker beaten in 1992 by police, who were subsequently acquitted of using excessive force. The beating sparked six days of rioting during which 63 people were killed.

“We also looked at Dallas, New York and Chicago,” Meyer says. “Orlando was at the bottom of everyone’s list but turned out to be the right spot.” The vote to move to Orlando was 3-2, with Meyer in the minority.

“I was all for moving to California,” he says. “Orlando in my mind was still a little town. Compared to Toronto, 26 years ago, Orlando was the boondocks. I struggled with it. It took me a good two years to call this home.”

Meyer’s most pressing concern was education. He and his wife, Giliane, had school-age children, Curtis and Celeste. “Florida was rated number 48 out of 50,” Meyer says. “I didn’t want my kids growing up in a place that didn’t give your kids a decent education. I knew two people in Florida at the time and both said the only good [public] schools are in Winter Park. We never even looked anywhere else.”

Curtis, now 35, and Celeste, 32, attended Brookshire Elementary, Glenridge Middle and Winter Park High. “I’ve always been the coolest dad in the neighborhood,” Meyer laughs. “I’ve done lots of school presentations and show-and-tell for many classes. I took valuable stuff and let kids touch it. I’d wrap an anaconda skin around them, put tiger shark jaws over their heads.”

Pity the parent on career day who had to follow Meyer’s act. “Yeah, I’d blow ‘em out of the water,” he says. “The fireman has a chance, but the doctor and accountant might as well go home before they start. I was a major hit for years and years. They almost cried when I said I don’t think I can do it this year because I don’t have access to the stuff anymore.”

For about 25 years, from age 25 to 50, Meyer nearly qualified as a Ripley’s exhibit himself. He had a morphing two-toned beard — brown and red, then brown and white — the result of a childhood pigment condition.

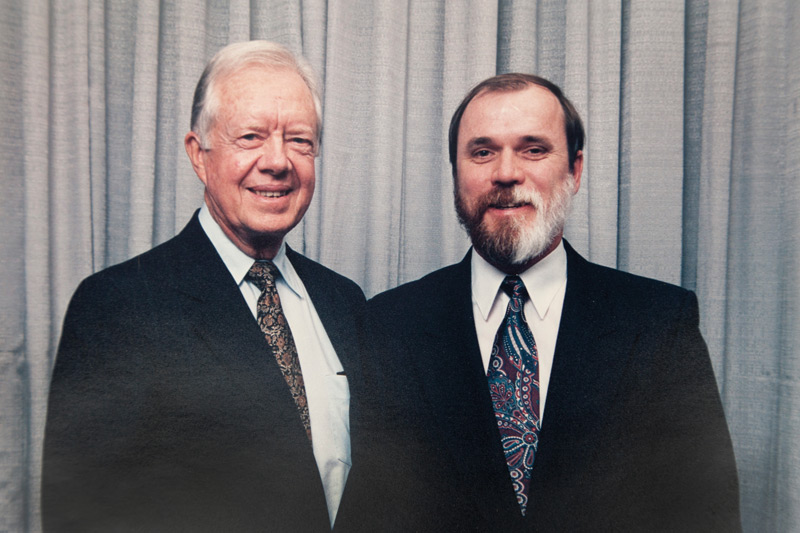

“It took me years to convince people it was real,” he says. “For many years people thought I got my job because of the beard. Sometimes I would tell them the truth, sometimes I wouldn’t. That beard got me to a lot of places. I’ve met six presidents. I met Jimmy Carter twice, several years apart, and that’s what he remembered: ‘You’re the guy with the two-toned beard!’”

Not anymore. Meyer’s beard, if he didn’t shave, would be uniformly white — a badge of seniority. Teasingly, I asked the man who’s visited 42 countries if he looks forward to traveling in retirement.

“Yeah, I do,” he says. “There are still places I want to go for sure, like Egypt. But I don’t know if I can afford to travel. I spent too much on things. I haven’t been real good at saving.”

So, believe it or not, Edward Meyer, once holder of The Most Interesting Job in the World, is now like so many of us nondescript retirees — just another housebound guy in cargo shorts waiting for the contractor to show up.

Maybe the only way Meyer will get to Egypt is via his armchair. But he lives in a museum (might as well admit it, Ed), his own personal odditorium, surrounded by the things he loves. And what his childhood librarian in Toronto said is true of all that Edward Meyer surveys from his beaded African throne:

“There’s a world in this building that’s at your fingertips.”