There’s a small, unassuming, black-and-white photograph of the late Fred Rogers on a hallway wall in Hume House, a preschool and child-development research center on the westernmost edge of the Rollins College campus.

The 1990 photo was taken during a visit to the center by the beloved Rollins grad, whose revolutionary PBS show for young children, Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, represented a one-man crusade to nurture their pilgrim hearts and minds — and to buffer both from the cacophony of the modern world.

In the photograph, Mr. Rogers sits in a chair encircled by children. He wears one of his trademark cardigans and beams with that front-porch glow of attentive delight the presence of children always inspired in him.

Something akin to that expression would surely cross his face if he could see what the old neighborhood is up to these days.

Guided by a multidisciplinary research team, Rollins students have been introducing preschoolers to the wisdom of the ancients, using traditional early-education activities to examine concepts that great philosophers sought to bring to early civilization: fairness, bravery, self-control, civility. It’s part of a multitasking enterprise meant to plant thoughtful seeds in both the younger and the older students.

Five years ago, as part of an initiative to incorporate elbow grease into the liberal arts, Rollins philosophy professor Erik Kenyon was asked to add a community outreach component to his classes.

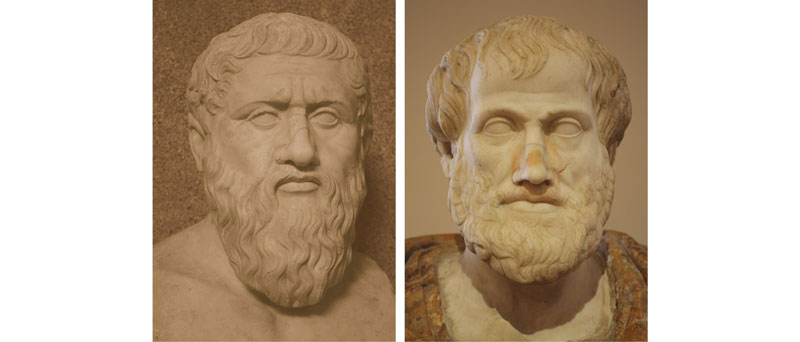

Kenyon, a youngish 38-year-old with striking blue eyes and a preppy haircut, is more likely to be taken for a student rather than a philosophy professor as he rides his bike to and from classes. In truth he is an old soul by association, so thoroughly marinated in ancient and medieval philosophy that a student once described him to me as “Aristotle reincarnated.”

Well, it’s one thing to channel Greek philosophers to a captive classroom audience. It’s another to trot your musty Hellenic homeboys around off campus. The notion seemed idealistic to Kenyon. Or as he put it: “I thought, ‘What am I supposed to do? Save the whales?’”

Then he remembered the work of colleagues elsewhere who developed the so-called “P4C” educational program. P4C stands for “philosophy for children” and consists of a series of lesson plans that can be used to introduce grade-school students to rudimentary philosophical concepts.

In 2015, Kenyon began incorporating P4C ideas into classes that called for his students to develop child-oriented philosophy lessons as part of their studies — then take them on the road. Things went smoothly when they worked with students at nearby elementary schools.

With preschoolers, not so much. Nothing in Augustine’s dialogues or Plato’s pedagogy addresses the existential realities of trying to engage a tribe of rambunctious 3- and 4-year-olds with lesson plans designed for elementary school students.

“There was a lot of running away and hiding in corners,” says Kenyon, of his team’s first visit to Hume House. “It was a disaster.” He looked to the center’s director, Diane Terorde-Doyle, and Rollins psychology professor and longtime Hume House crusader Sharon Carnahan for help.

“Children at this age think with their bodies,” offered Terorde-Doyle. Yet, added Carnahan, they’re perfectly capable of grasping abstractions: “They’re stone experts on friendship.”

So, hoping to connect with preschoolers on their own turf, the team began developing lesson plans rooted in physical activities; sharpened them to revolve around ethics, the branch of philosophy that addresses relationships and behavior; and focused on questions that addressed daily life from a preschool perspective — such as, “what makes a family?”

An obvious ingredient volunteered by the children in discussions one day was “love.” Then a little girl added a wise-beyond-her-years distinction.

“I agree that if there is a family, there is love,” she said. “But I disagree that if there is love, it has to be in a family.”

The moment convinced Kenyon the project was on track. “That’s the kind of thing that a college logic course wouldn’t get to around to until week four,” he says.

Overall, the effort prompted such a shift of perspective at Hume House that, this year, the three researchers published a book about their efforts, Ethics for the Very Young.

The book includes outlines of lesson plans meant to encourage children to “listen, think, and respond” in order to navigate their way through questions such as: What is bravery? What is a friend? What makes something fair or unfair? How do I agree, or disagree, with dignity?

All it takes is a quick visit to a couple of internet chat rooms to see that the culture at large could use a few lesson plans on that last one.

Michael McLeod is a contributing writer for Winter Park Magazine and an adjunct instructor in the English department at Rollins College.