More than a century ago, during the winter months, wealthy Northerners ensconced themselves at luxury resort hotels in fledgling Winter Park. Many visitors ended up investing in the community and ultimately moving here.

By the 1930s and 1940s, middle-class families were flocking to more modest accommodations — including tourist cottages — along U.S. Highway 17-92 (the colloquially named “Million-Dollar Mile”). And by the 1950s, Winter Park boasted the swank and swinging Langford Resort Hotel, where the Empire Room supper club epitomized Rat Pack culture.

The Winter Park History Museum, consequently, has been saluting the golden age of local hotels and motels in its current exhibition, Wish You Were Here: The Hotels & Motels of Winter Park. The exhibition runs until June 6, 2020.

The cozy museum space is packed with sometimes-kitschy ephemera from the city’s classic motels and motor courts — including a re-created guest room using authentic furnishings, right down to the matchbooks and the Gideon bible in the end-table drawer.

Also examined are the luxurious resort hotels that attracted monied Northerners to Winter Park in the late 1880s. There’s even a re-imagined Victorian-era children’s playroom of the sort where guests of the posh Seminole Hotel or Alabama Hotel might have stashed their youngsters while they were out boating.

A nostalgic highlight of the exhibition is the original piano from the Empire Room as well as the hotel’s poolside bar from which untold gallons of tropical drinks were served. And take time to read the wall panels, which are dense with vintage photographs and carefully researched descriptions.

Linda Kulmann, the museum’s archivist and past board president, wrote the panels, which range from histories of early boarding houses to a locator map of mom-and-pop motor courts once located along U.S. Highway 17-92 (also known as Orlando Avenue).

Susan Skolfield, the museum’s executive director, says artifacts on display for the exhibition were donated or loaned. The Langford piano, for example, was loaned by the family that purchased it at auction when the hotel closed.

“Because our space is small, every item has to mean something,” adds Skolfield, who says more than 20 volunteers began scouting for materials a year in advance of the exhibition’s opening. “We’re always creating as we go along.”

Helping to make the most of the space — which measures less than 1,000 square feet — is Camilo Velasquez, an art instructor at Valencia College, Rollins College and the Crealdé School of Art.

“You might say I’m the make-up man,” says Velasquez, who stages and designs most of the museum’s exhibitions. Creative use of lighting and object placement can make the compact venue appear larger, he says.

Home Away from Home

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the exhibition is the emphasis on the Million-Dollar Mile, which was a much more modest destination than its hyperbolic name suggests.

Its friendly vibe and affordably priced accommodations appealed to middle-class travelers, who for several decades created something of a subculture along U.S. Highway 17-92.

Which begs the question: Why did these visitors come to Winter Park instead of Orlando, a much larger city? Why, for that matter, did they come to Winter Park instead of New Smyrna Beach or Daytona Beach? Wouldn’t a vacationer driving from the icy Midwest or Northeast find a beach destination more appealing?

Of course, Winter Park had attractions of its own. There was quaint Park Avenue for shopping and a gorgeous Chain of Lakes for recreation. Rollins College, the state’s oldest institution of higher learning, enlivened the cultural scene for residents and visitors alike. And the beaches weren’t far away by car.

But the Million-Dollar Mile’s appeal may have had more to do with its folksy ambience. It was an unfussy home away from home, sans the snow.

“Families from up north built long-term relationships with the motor court owners and just kept coming back,” speculates Kulmann. “Some of it was probably familiarity.”

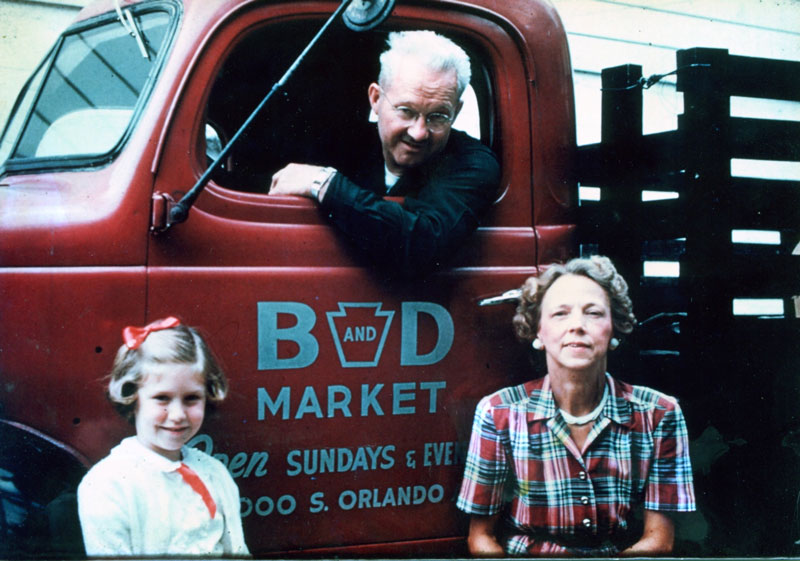

Local historian Joy Wallace Dickinson, whose grandparents owned a grocery store on the periphery of the Million-Dollar Mile — B and D Market, at 1000 South Orlando Avenue — agrees.

“People also tended to stay in places their friends told them about,” she says. “There were plenty of annual visitors who just enjoyed it here and spread the word among their friends. A kind of community developed.”

It didn’t hurt that Winter Park was a convenient place to stop en route to South Florida, Dickinson adds. “It’s right in the middle of the state,” she says. “I expect quite a few people who stayed along the Million-Dollar Mile were coming back from, or were on their way to, someplace else.”

Dickinson, who recently gave a presentation about Winter Park’s motor court heyday during the museum’s monthly membership meeting, noted that Orange Blossom Trail — today synonymous with sleaze — was once also dotted with family-oriented motels, including the eye-catching Wigwam Village, which was demolished in 1973.

Virtually all of Winter Park’s motor courts were mom-and-pop, meaning that they were literally owned and managed primarily by husbands and wives — many of whom lived and raised families in the motor courts that they managed.

For travelers, it was comforting to be greeted warmly by a hospitable couple who would meet them at the office door, personally escort them to their rooms or cottages, and help them unload their luggage.

Many were annual extended-stay customers who developed close friendships with the owners. The courtyards created a back-home familiarity as both owners and travelers gathered for evening conversations while children frolicked in courtyard pools and playgrounds.

Old acquaintances were renewed and new acquaintances were made as guests gathered to gossip and swap tales of their road experiences. They dined nearby at Anderson’s Restaurant, grabbed a burger at Roper’s Grill — which boasted one of the first “animated” neon signs in Central Florida — or enjoyed a sugar fix at the Donut Dinette.

If it was a special occasion, D’Agostino’s Villa Nova or the Imperial House — “where the royal rib reigns supreme” — offered more upscale options. In nearby Orlando, nightclubs advertised programs packed with comics and crooners.

It should be remembered, however, that such idyllic getaways were available only to white families in the Jim Crow era. Prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, African-American families often consulted The Negro Motorist Green Book to find lodgings, businesses and gas stations that would serve them. Likely, none in Winter Park would have been listed.

Wright’s Motor Lodge (300 South Orlando Avenue), built in the 1930s by Mr. and Mrs. Herbert B. Wright, was one of the first to be constructed along the Million-Dollar Mile. By the 1950s it was owned and operated by Mr. and Mrs. J. Stephan.

A postcard printed by the Stephans touted Wright’s — they hadn’t changed the name — as “the right place to stay.” Other advantages: “New fireproof buildings. Private baths with tile showers. Plenty of hot water at all times. Innerspring mattresses. Insulated rooms. Cool in summer, warm in winter. Cottages off the road.”

Down the road at 848 South Orlando Avenue — today the site of a Steak ’n Shake — was Baggett’s Cottages, described as “modern in every respect” with a location “in the midst of an orange grove where guests can pick their own oranges right off the tree.”

Other motor courts with identifiable owners included Dandee Cottages (103 North Orlando Avenue) owned by Mr. and Mrs. Edward Wittman; 17-92 Motor Court (401 North Orlando Avenue) owned by Mr. and Mrs. D.I. Sigman; Colonial Motor Court (400 South Orlando Avenue) owned by Mr. and Mrs. Jim Ward; and Greystone Manor Motor Court (700 South Orlando Avenue) owned by Mr. and Mrs. Carl Bleyl.

The Lake Shore Motor Court (215 South Orlando Avenue) exemplified the best of these mom-and-pop operations. It was a member of Quality Courts United — now the Choice Hotels International chain — which was formed in 1939 by seven independent owners who established mandatory quality standards and referred business to one another.

As it grew and morphed into a franchise, Quality Courts United also worked to overcome negative perceptions of motor courts as either seedy or hideouts for gangsters and other undesirables.

Members were endorsed by the American Automobile Association and received a stamp of approval from nationally known travel and food writer Duncan Hines.

In its brochures, the Lake Shore Motor Court touted its Quality Courts United membership as well as its playground and its private beach on Lake Killarney. Promised one promotional flyer: “The accommodations are certain to please the most fastidious of travelers and vacationers.”

Changing Times

The three-decade motor court era in Winter Park was not destined to last. Fundamental changes in the roadside-accommodation industry were well underway by the 1970s.

By the late 1950s, some motor courts had added second stories and offered amenities normally associated with downtown hotels. These larger accommodations were advertised as “motels,” a portmanteau of motor and hotel.

Individually owned motels became cookie-cutter corporate properties designed to resemble downtown hotels. Holiday Inn was an early example of such a franchise. Quality standards may have become more predictable, but the quirky charm of motel architecture from the 1920s through the 1950s was lost forever.

Additionally, multistory accommodations such as Winter Park’s legendary Langford Hotel contained all the amenities of a downtown hotel as well as parking facilities and an outdoor pool of the sort ordinarily associated with roadside motels and motor courts.

The Langford, located at the corner of New England and Interlachen avenues, was also within walking distance of Rollins and Park Avenue. It was closed in 2000 and demolished in 2003. The upscale Alfond Inn, developed by Rollins, now occupies this choice piece of real estate.

These developments, along with the construction of Interstate 4 and the arrival of Disney World — which spurred construction of countless hotels on and around the attraction — led to the decline and, by the 1990s, the demise of motels and motor courts along U.S. Highway 17-92.

“The small, family-owned motels, where friends meet on vacations and return year after year to the same kitchenettes and swimming pools, may soon go the way of downtown grocery stores and 35-cent gas,” wrote the Orlando Sentinel in 1979. “For the remaining ‘ma and pa’ motels along U.S. Highway 17-92 in Winter Park, the future appears bleak.”

When the iconic Mount Vernon Inn (110 South Orlando Avenue) was razed in 2015, Winter Park lost the last remnant of motel culture along the Million-Dollar Mile, which is now brimming with new dining and retail projects. These days, motorists can’t even see Lake Killarney from the traffic-choked highway.

There is, however, one remaining vestige of those simpler days: La Siesta Court was located at 325 South Orlando Avenue. Today it has retained its U-shaped bones but has been refashioned into a series of retail stores, including the popular Black Bean Deli.

Wish You Were Here, like all History Museum exhibitions, is free and open to the public — although donations are gladly accepted. The museum is in the Farmers’ Market building at 200 West New England Avenue.

Hours are Tuesday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. For more information, visit wphistory.org.

Portions of this story incorporate research by Jack Lane, professor emeritus of history at Rollins College.