Winter Park’s most high-profile rite of spring is the Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival, which was held for the 60th year on March 15, 16 and 17 in Central Park. As many as 300,000 people, according to estimates, jammed the downtown business district to tour what has for decades been one of the most prestigious juried outdoor art extravaganzas in the Southeast.

Many locals wouldn’t miss it. Many others steer clear because they can’t abide the crowds. In either case, few can remember a time when there wasn’t an art festival in Winter Park. And fewer still know how it all began. So, as the 60th annual event wraps up, it seems an appropriate time to explore its at-times tumultuous history.

Remember 1960? Dwight D. Eisenhower was still president of the United States. But John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon were headed for the Democratic and Republican nominations, setting up an epic battle that would culminate with a narrow win for the young senator from Massachusetts.

The tumult associated with the ’60s — Vietnam, assassinations, mass protests, racial unrest, the sexual revolution and more — was largely yet to come.

Beatniks weren’t yet hippies, and Elvis — back home from serving in the U.S. Army in Germany — notched two of the year’s Top 10 records: “It’s Now or Never” and “Stuck on You.”

Along Park Avenue, you could see a movie at the Colony Theater, check out the latest fashions at Proctor Center and scarf down an ice-cream sundae at Irvine’s Pharmacy or the Yum Yum Shop.

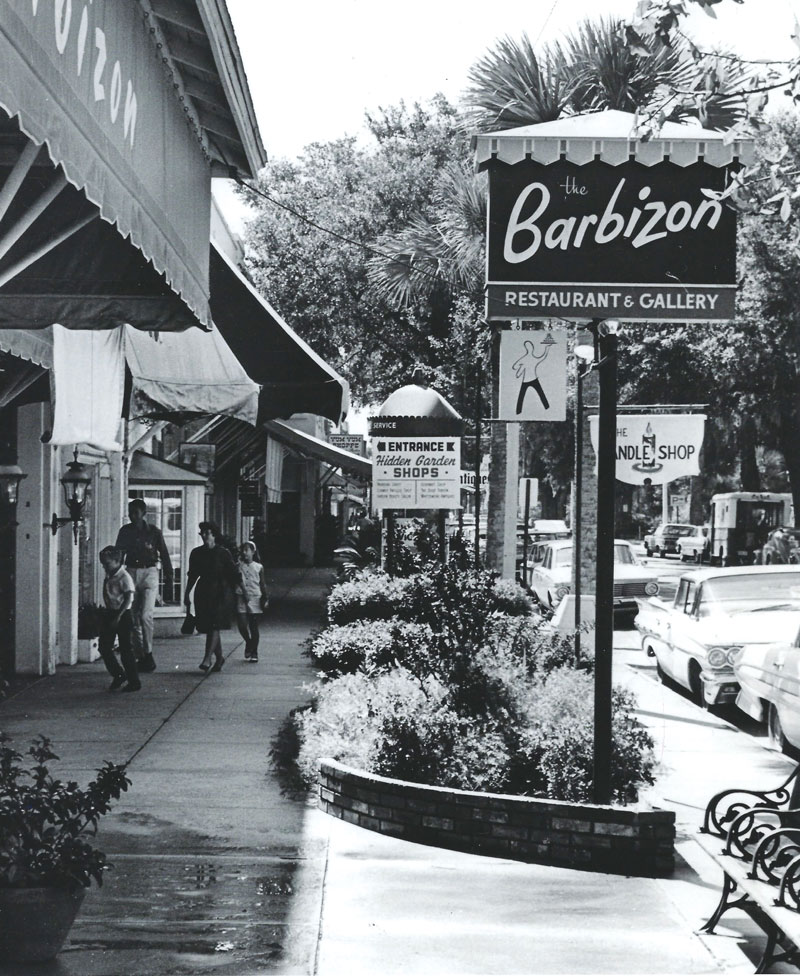

But in January of that year, local history was made at the Barbizon Restaurant and Gallery — located at the corner of Park and Canton avenues, where Boca is now — when a group of friends who met regularly to while away slow afternoons hatched an audacious idea.

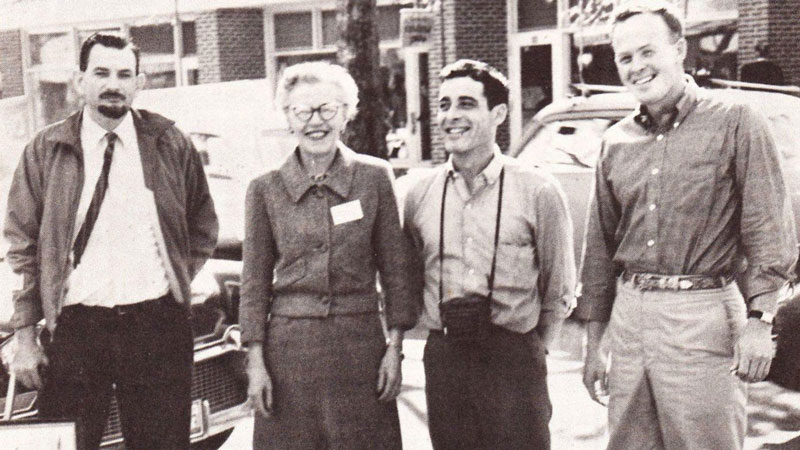

Those present were Darwin Nichols, a potter who owned the restaurant, and artists Robert Anderson and Don Sill, who shared a nearby studio in the Hidden Gardens. Perhaps there were others — accounts vary — but Nichols mentioned only Anderson and Sill in a 2009 interview with Winter Park Magazine. All three have died in the past decade.

In any case, those present reached a consensus that an outdoor art festival could be pulled together in a short time.

Said Nichols: “We were sitting there having a glass of wine and we were thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if we had a place where nonprofessional people — those not accomplished enough to be in galleries — could show their work?’”

It only made sense. Local artists already displayed paintings at the Barbizon, where diners could buy them right off the walls. Plus, the gallery-packed city had a longstanding reputation as an artists’ colony.

But organizational savvy was needed, so the friends recruited, among others, Edith Tadd Little, a patron of the arts — indeed, an artist herself — and for a time owner of an interior design business on Park Avenue.

Little’s involvement all but assured success. A civic leader and booster of cultural causes, she had been designated “Mrs. Winter Park” in 1959 by the city commission. Revered for her energy and organizational acumen, some local businesspeople had affectionately nicknamed her “The General.”

Among Little’s artistic credentials: She decorated the interior of the Annie Russell Theatre on the campus of Rollins College, even creating the stencils and painting the elaborate designs that adorn the ceiling.

“Mother’s original idea was to have the festival for all the local artists and the art departments of all the schools, from kindergarten through college,” recalled the late Sally Behre, Little’s daughter, in a 1987 oral history interview with the Winter Park History Museum.

But The General — who died in June 1960, just months after the inaugural event — was too ill to lead the charge. (From 1965 through 1968, the Best of Show award would be named the Edith Tadd Little Medal in her memory.)

Jean Oliphant, another formidable mover and shaker, chaired a hastily formed 18-member festival committee — its meetings were held in the Barbizon’s Blue Room — on which Little and about a dozen others served. (Oliphant, who died in 1990, would become known as “The Mother of the Sidewalk Art Festival.” Although some news stories place her at the initial “bull session” with Nichols, Anderson and Sill, it’s more likely that she joined the effort immediately thereafter.)

Nichols agreed to kick in $50. Soon, Park Avenue merchants — delighted at the prospect of drawing potential customers to the quaint but sometimes-sleepy business district — stepped up to help defray expenses for what was initially billed, rather generically, as a “Sidewalk Art Show.”

Bohemian Rhapsody

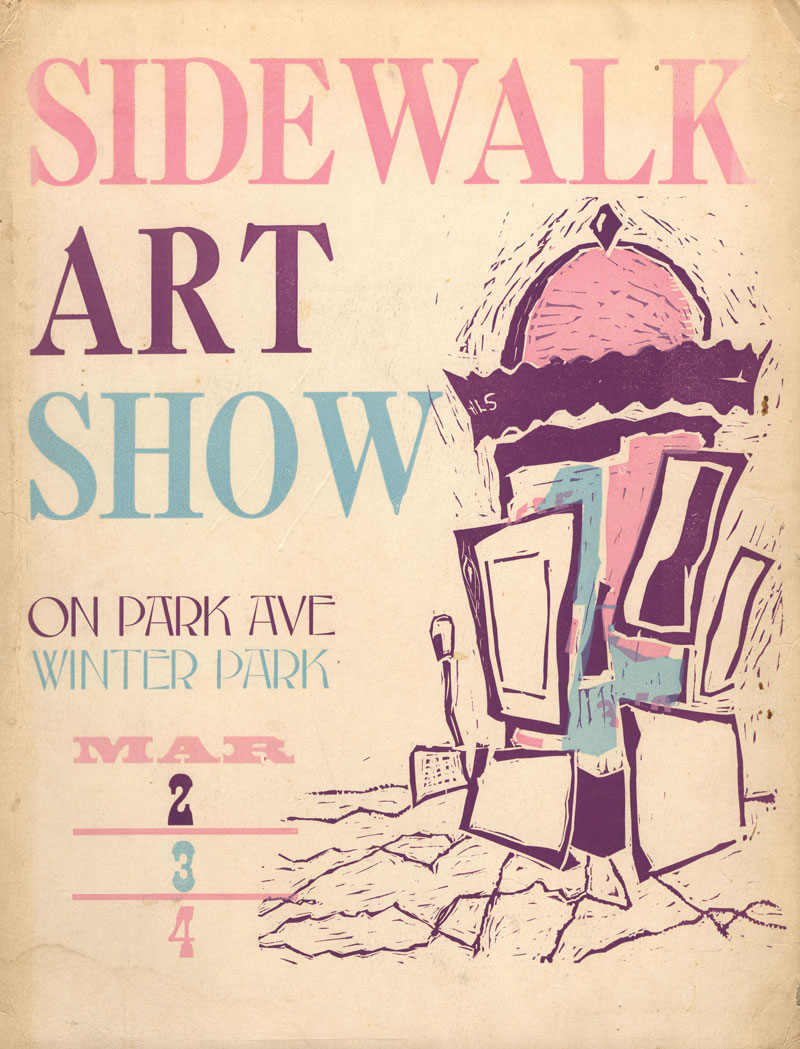

In early February 1960, the Orlando Evening Star announced the news with the headline: “Date Set for ‘Arty’ Park Ave. Three Days of Bohemia.” Just three weeks later, on March 3, 4 and 5 (Wednesday, Thursday and Friday), the inaugural event was held.

For artists, promptness was the most important requirement. The first 90 to apply were accepted, and there was no entry fee. Regardless, thousands showed up to see painters, weavers and even makers of puppets and sundials. Schoolchildren also exhibited their creations.

“None of us were prepared for the onslaught of people coming,” said Nichols, who died in 2016. He had clearly underestimated the allure of picture-postcard-pretty Park Avenue on a spring afternoon.

“It was the windiest day I think we’d had in a long time,” noted Behre in the 1987 interview. Her young students from the Jack and Jill Kindergarten hung their paintings from a clothesline and chased them down when sharp gusts sent their colorful creations soaring.

“[Artists] just had easels,” Behre recalled. “They didn’t have booths or anything like they have today. They would stack [their work] up at night, and Boy Scouts took turns sleeping in the park and patrolling the place.”

By all accounts, despite the indiscriminate selection process, some very good work was displayed.

The 1960 Best of Show winner — an oil painting of a foreboding forest by DeLand artist Arnold Loren Hicks — was selected by attendees who filled out ballots. A grateful Hicks — who had sold four of his paintings over the weekend — donated his $40 windfall back to the festival to help ensure that it would continue.

It proved to be a wise investment; Hicks would win again in 1961, when the festival was compressed into two days and moved to Friday and Saturday. (From 1964 forward, it was a three-day event beginning on the third Friday in March.)

Hicks, like all Best of Show winners, has an interesting backstory. By 1960, he was primarily a landscape painter. Early in his career, however, he painted lurid covers for pulp magazines and was a cartoonist for the legendary Classics Illustrated comic-book series.

But Hicks wasn’t the only cartoonist-turned-fine-artist in the first festival. Frank King (“Gasoline Alley’’), Les Turner (“Captain Easy”) and Roy Crane (“Buzz Sawyer’’) also displayed the products of their painterly pursuits. All three lived in Winter Park.

Another notable entrant — one whose participation instantly cemented the festival’s cultural credibility — was Jeannette Genius McKean, who displayed a selection of geometric abstracts.

McKean was the granddaughter of industrialist and Winter Park benefactor Charles Hosmer Morse, in whose honor she named the Morse Gallery of Art on the Rollins campus. That museum would later become the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art on North Park Avenue.

An accomplished businesswoman in her own right, McKean owned the Center Street Gallery, which showcased up-and-coming Florida artists, and was president of the Winter Park Land Company, which managed her grandfather’s vast holdings.

She was married to Hugh F. McKean, a former art professor who had become president of Rollins in 1951. A nod from the McKeans — Winter Park’s original power couple and the embodiment of its artistic ambience — would have been important to festival organizers.

The puzzle pieces came together. Yes, the event was hurriedly staged, but its supporters and organizers were civic dynamos who knew how to make things happen. Still, not even the most ardent boosters could have predicted what was to come.

In 2019, the Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival encompassed 225 artists vying for sales and a share of $74,500 in prize money. National publications such as Sunshine Artist, Art Fair Calendar and Art Fair Source Book frequently place the event at or near the top of their rankings.

“I don’t know why it caught on like it did,” said Nichols in 2009. “I guess Winter Park is just an artsy place.”

Best of the Best

While much about today’s festival is the same as it was 60 festivals ago, much is also different. Most notably, it’s no longer a showcase for enthusiastic local hobbyists.

The juried event has for decades attracted roughly three times as many applicants as it has exhibit spaces. Participants and winners are selected by an independent trio of highly credentialed experts from outside Central Florida.

But despite its size and sophistication, the whole shebang is still run by volunteers who’ve turned festival production into, well, an art form. The umbrella organization is called Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival Inc., a 501(c)4 not-for-profit corporation that consists of about 40 people on its board and executive committee.

And there’s plenty for everyone to do. Despite its seat-of-the-pants starting point, the event quickly morphed from a casual weekend stroll in the park into a full-fledged regional happening with multiple components.

In the early ’60s, entertainment began to be an important part of the festival experience. Students from the Royal School of Dance performed an original ballet, while nightclub entertainer and restaurateur Chappy McDonald tickled the ivories and sang.

There were folksingers — including Gamble Rogers IV, the iconic architect’s son who would go on to have a legendary career as a balladeer — as well as high school bands, jazz combos, barbershop quartets and symphony orchestras.

The number of artists also grew — there were 240 in 1963 and 300 in 1964, when the Best of Show winner earned a whopping $500. That year, the festival promoted itself as an event where “every artist and craftsman has an opportunity to show his creative ability.”

Soon, that egalitarian approach would change.

Crowds swelled, with up to 200,000 estimated in 1964, when outside judging was introduced. Park Avenue was closed to traffic for the first time in 1965. That year, an illustration of a festival scene was featured on the cover of the Winter Park Telephone Company’s city directory.

Local institutions began donating money or sponsoring major awards, including First National Bank of Winter Park, Minute Maid, the Tupperware Company and the Winter Park Telephone Company. Other companies sponsored various category-specific awards.

The “is it really art?” question inevitably arose in the ’60s, when crocheting, knitting, millinery, clothing and picture frames were prohibited. Painting, of course, was really art, as were crafts such as ceramics, mosaics, pottery, weaving and wood carving. (Decorated eggs were explicitly judged not to be art in 1969 — a decision that didn’t go over easy with the artist seeking to display them.)

By 1966 the number of participating artists had mushroomed to 600, and the festival encompassed Park Avenue from Fairbanks Avenue all the way north to Canton Avenue and throughout Central Park.

But, as far as outdoor art festivals are concerned, bigger isn’t always better. A consensus emerged that the event had become simply too overwhelming for attendees to enjoy, and it was scaled back to 425 artists the following year. (It was capped at 225 artists in 2009.)

The Winter Park Chamber of Commerce sponsored the festival from 1963 through 1966. The City of Winter Park — eager to control what had become the city’s most notable event — created a commission consisting of current volunteers and political appointees to take over festival operations in 1967.

Founding member Jean Oliphant’s husband, Frank, was a city commissioner who supported the idea. “Frank told Jean, ‘If you have a brain in your head, you’ll involve the city in your little ladies’ festival,’” recalls Jean Sprimont, a festival board member since 1987.

(This arrangement persisted until 1989, when complications stemming from Florida’s Sunshine Law — which required that all governmental meetings be advertised and open to the public — made planning too ponderous. “We had to be able to talk to one another,” says Carole Moreland, a festival board member since 1978. “Under those circumstances, we couldn’t get anything done.”)

In 1969, the festival began the tradition of buying the Best of Show-winning work and donating it to the city. A year later, the “first come, first served” selection process was dropped. Applicants were required to submit three color slides for screening by judges — and competition became fierce.

By 1972, some local artists had begun to complain that too many out-of-towners were invited to exhibit, while locals — taxpaying citizens, mind you — were excluded. Mayor Dan Hunter, perhaps naively, said he had hoped “to keep politics out of the festival.” Still, he agreed to listen to the aggrieved artists.

Ultimately, however, festival jurors were permitted to continue considering only the quality of the artist’s work — not whether the application carried a 32789 zip code — as their primary criteria.

“This wasn’t what we call a Sunday painter’s show,” said architect Keith Reeves, who served as a festival chairman in the ’70s and spoke to Winter Park Magazine in 2009. “Everybody felt like that if this show was going to have any merit or recognition that it had to truly be a juried art show — that you just couldn’t be a favorite son and get in.”

In the wake of that controversy, painter Sissie Barr led an effort to start a festival that would showcase only Florida artists. The Winter Park Autumn Art Festival debuted 1974 and was sponsored by the now-defunct Winter Park Sun-Herald. By the ’80s, it was co-sponsored by the Crealdé School of Art and the Winter Park Chamber of Commerce.

Now sponsored exclusively by the chamber, the autumn festival was moved from Central Park to the Rollins campus. It was later staged in Island Lake Park and finally found its way back to Central Park, where it has become an October tradition and remains the only juried outdoor festival featuring only Florida artists.

Where’s Dorothy?

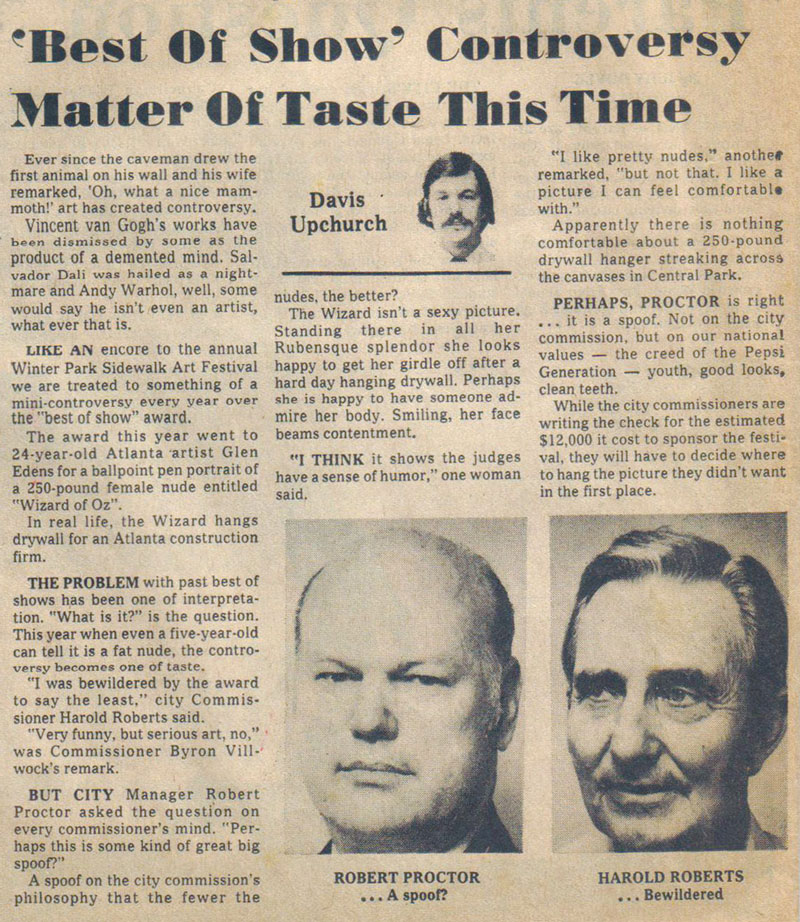

In festival lore, 1975 will always be remembered as the year of the naked lady.

Glen Eden, a 24-year-old art school student from Atlanta, won the festival’s Best of Show award and the $1,000 prize it carried with The Wizard of Oz, a photo-realistic ballpoint pen drawing of a rotund middle-aged woman wearing nothing but a shocked expression.

The woman, said Eden, was a real person named Dorothy, who was a wallboard installer whom he had met at his apartment complex.

Prior to 1978, works that snared Best of Show honors were displayed in City Hall. (Today, the Best of Show Collection hangs in the Winter Park Public Library.) But there was no chance — none whatsoever — that city commissioners were going to display a drawing that showed full-frontal nudity, regardless of the model’s physique.

“It’s the kind of thing you’d hang on your refrigerator door to keep from opening it,” as Commissioner Byron Villwock described the work to an Orlando Sentinel reporter in stories headlined, “City Hall Can’t Bare New Portrait” and “‘Best of Show’ Controversy a Matter of Taste This Time.”

Because the city wouldn’t give Dorothy a home, Reeves adopted her and displayed Eden’s award-winning work in his own home until the furor died down. The drawing did eventually hang in the library for several years — but mysteriously disappeared in 1982.

Oh, you can still see it — sort of. A reproduction of the provocative image can be seen in the library, lurking in an obscure corner on the third floor. It’s faded from exposure to sunlight and much smaller than the poster-sized original.

Dorothy’s presence, diminished as it may be, is thanks to Robert Melanson, library director for 25 years until his retirement in 2012. In 1994, he asked Phil Eschbach, owner of Eschbach Photography, to take a picture of a photocopy stored in the library’s archives. He then had the picture framed and hung.

“The library was supposed to be the repository of Best of Show winners, and this one wasn’t there,” says Melanson, who never saw the original and had only heard stories about the brouhaha. “I didn’t believe that whoever took it ought to be allowed to censor the collection.”

What became of the original remains a mystery, although it has been speculated that someone connected with the city — and therefore someone with access to the library after hours — must have been involved.

“Ever since cavemen drew the first animal on the wall, art has created controversy,” wrote the late Elizabeth Bradley Bentley in her lively book, A Side Walk with the Art Festival, published to commemorate the festival’s 20th year. “There is nothing like a good controversy to show how such an important thing as art can still get us all riled up.”

Also in 1975, city grant money dried up and the festival was expected to become self-supporting. An emphasis was placed on raising money through application fees for artists, franchise fees for food vendors and the sale of merchandise, such as posters and T-shirts.

In 1979, tensions among art festival board members boiled over when the results of an election for executive committee offices — including president and vice president — were disputed.

About half the group resigned over the turmoil, which saw Bruce Cucuel, then director of drawing and painting at the Crealdé School of Art, unseat previous president Gerry Shepp, then executive director of the Maitland Art Center.

Among those who remained to rally the troops: Jean Oliphant, treasurer and founding member whose institutional knowledge proved invaluable as eager newcomers were welcomed to lead the festival into its third decade.

The event never missed a beat. Or if it did, artists and spectators never noticed. To commemorate the festival’s 25th year in 1984, the Albin Polasek Foundation gave the city a recast version of the late sculptor’s iconic statue, Emily, to be placed in a circular fountain in north Central Park now called “The Emily Fountain.”

The original Emily is on the grounds of the Albin Polasek Museum & Sculpture Gardens on Osceola Avenue. Like Dorothy, Emily is unclothed, although her bare breasts sparked no apparent outrage at the time. The statue was, however, vandalized the following year and recast.

All That Jazz

Musical entertainment has always been a part of the festival, but in the early days it consisted primarily of local performers and performing arts troupes. Periodically, the Florida Symphony Orchestra — which went defunct in 1993 — would present a Sunday afternoon concert.

But entertainers were forced to perform either on the lawn or from makeshift stages (including, on several occasions, the beds of pickup trucks). In 1980, the symphony threatened to pull out of its Sunday afternoon performance for fear that inclement weather might ruin its instruments.

The resourceful Cucuel rented a large parachute and strung it over tree branches in the northeast quadrant of the park to provide cover for the musicians. The show went on, but clearly a more permanent solution was needed.

Enter the Rotary Club of Winter Park, which in 1982 funded construction of the permanent — and covered — Centennial Performing Arts Stage in north Central Park. (The stage’s seldom-used original name honors the city’s centennial, which was celebrated that year.)

In 1983, the stage debuted as the centerpiece for “Friday Family Night,” which featured the Ballet Royal and Family Tree, a local folk trio that had an avid following at Harper’s Tavern, Uncle Waldo’s and other Winter Park venues.

In subsequent years, though, the genre was all jazz, with headliners such as Herbie Mann (1986), Dave Brubeck (1987), Al Hirt (1988), Ramsey Lewis (1991), The Rippingtons (1993), Grover Washington Jr. (1997) and Boney James (1998).

Entertainment was initially funded by the festival, which recruited such sponsors as Barnett Bank, MetLife HealthCare Network, Pioneer Savings Bank, Sun Banks and the Winter Park Telephone Company.

Only once since construction of the stage was there no Friday night concert. In 1989, some previous sponsors — most notably Sun Banks — decided instead to support the newly launched United Arts of Central Florida.

United Arts was conceived by Orlando Mayor Bill Frederick as a more cohesive way of helping to fund a consortium of cultural groups that were each chasing the same donors. The festival, however, was not among the initial dozen United Arts beneficiaries.

Nonetheless, the event was back the following year with Scottish-born jazz saxophonist Richard Elliot, who had just launched a solo career after a decade with the funk group Tower of Power.

Perhaps no performer brought out fans in such huge numbers as vocalist Michael Franks of “Popsicle Toes” fame did in 1994. Franks was such a draw that people overflowed onto the train tracks running parallel to the park.

The emphasis on jazz was primarily due to the involvement of WLOQ-FM, a smooth-jazz radio station owned by the late John Gross, who had been recruited to the festival board because of his entertainment industry expertise.

In the early ’90s, WLOQ and Sonny Abelardo Productions assumed responsibility for the entire weekend of entertainment, including the opening-night concert, which had previously been organized by a committee consisting of festival board members.

When Southwest Airlines began flying out of Orlando International Airport in 1998, Gross secured a $45,000 entertainment sponsorship from the airline that involved both a presence at the festival and cross-promotion with the radio station. That arrangement would continue for 11 years, solidifying the entertainment budget.

It certainly didn’t hurt that the well-connected Abelardo had managed or produced many of the musicians he booked. In 1999, for example, he paired Grammy-winning pianist/composer Bob James, whom he managed, with acoustic guitarist Earl Klugh.

The 2012 festival featuring saxophonist Warren Hill was Abelardo’s last, ending a 22-year run that firmly established the event as a showcase for world-class jazz artists. “I did it as a tribute to John [Gross],” Abelardo says of his final contribution to the festival’s legacy.

“Sonny had contacts and incredible friendship with these bands,” says Chip Weston, a festival board member before going to work for the City of Winter Park as director of economic and cultural development from 2001-2008. “I wish people had a grasp of how fortunate they were to have had him.”

Weston remembers city officials growing concerned that the concerts were drawing too many people.

“The city didn’t want the jazz concerts being too popular, because people spilled over onto the train tracks,” recalls Weston. “We had to coordinate with other cities to let us know when trains were coming. And we had to stop bands from playing when trains approached. I remember kicking people off the tracks with their bottles of wine and picnic baskets.”

Following Gross’ death and the shuttering of WLOQ in 2012, Wayne Osley, president of Oz Media Productions, has run the show, arranging everything from the Friday afternoon opening acts, which feature young up-and-comers, to the evening’s main event. (This year’s headliner was Mindi Abair and the Boneshakers.)

Osley also organizes the Saturday lineup — which features an eclectic array of primarily local artists — as well as the Sunday afternoon finale. (This year, jazz took a holiday on Sunday when the festival booked the Orlando Philharmonic Orchestra for a concert in its Pops Series.)

While the closing of the radio station meant smaller sponsorship budgets for procuring talent, Osley says he doesn’t have any problems booking touring jazz musicians whose fans would gladly pay to see them.

“Jazz artists are the easiest people to work with,” says Osley, next year’s co-president of the festival executive committee. He says he usually has about $35,000 to work with for the entire weekend — about 15 shows in all. Everyone who performs gets paid, he adds.

For Tim Coons, the festival’s weekend of concerts offers an opportunity to introduce young acts who could one day make it big like the boy bands he has worked with in the past.

Coons, a 1976 Rollins graduate and president of Orlando-based Cheiron Records, has a knack for bird dogging up-and-coming performers.

He was the original producer of the Backstreet Boys and helped develop NSYNC. His most recent contribution to the boy band genre was Far Young. “I was slammed with boy groups for about 10 years,” he says.

Coons has been inserting twenty-something singers into the festival’s entertainment lineup since 2014. He brought in Far Young spinoff and former American Idol contestant Eben Franckewitz in 2015 and ’16.

This year he booked three aspiring stars with strong social media followings — Saagar Ace, Sydney Rhame and Alani Claire — to perform Friday afternoon.

“It’s a great place for young kids to develop in front of a big crowd,” says Coons, whose home near Rollins doubles as a studio. “It’s not like the crowd is there for them. It’s just less pressure. It’s just a very chill event.”

“Like a Jam Sandwich”

Or maybe the real magic of the Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival is how chill it appears to artists and visitors, who don’t see the year-round planning sessions and frantic rush in the final weeks to finalize details.

“It helps that many of us are close friends,” says Carolyn Bird, a festival board member since 1975. “We know each other’s strengths and weaknesses.” Adds Carol Wisler, a festival board member since 1985: “There’s such great camaraderie; we all know funny stories — some we’d like to admit and some we wouldn’t.”

Many of those funny stories are in the 20th-anniversary book by Elizabeth Bradley Bentley, who died in 1994. Toward the conclusion, she beautifully captures the spirit of the festival and its volunteers:

“As the years went by, my main wish was for health to make the work a pleasure, wealth enough to purchase the art I simply could not live without, faith enough to make myself believe the examples I’d purchased were good (though some did look better hung upside down). And to be needed and wanted to work for the festival. I want to spread it over my face like a kid eating a jam sandwich.”