When I was 12 years old, the age now of my youngest son, I became enthralled with astronomy. It was 1980, and I was living with my family in South Dakota, where the night sky was — and presumably still is — a spectacular sight to behold. It was easy to see the Milky Way once your eyes adjusted to the dark. And the view from horizon to horizon was almost entirely unencumbered.

At the same time, the Voyager 1 and 2 missions to Jupiter and Saturn were underway. In school, we saw incredible images that these spacecraft transmitted back to Earth from the outer solar system. To a sixth-grader with a big imagination, the impact was profound.

It was serendipitous, then, that in 1980 Carl Sagan’s brilliant TV series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage premiered on PBS. Every Sunday evening for 13 weeks, I was transfixed by a program that would eventually be seen by 500 million people worldwide.

The New York Times referred to the premier of Cosmos as “a watershed moment for science-themed television programming.” It was certainly a watershed moment for me. To this day I remain fascinated by the mysteries of the universe.

One of Sagan’s greatest gifts was as a communicator of science. I was so enthralled that I became a huge Sagan fanboy and wrote him a letter at Cornell University, where he was a professor of astronomy and director of the Laboratory for Planetary Studies.

I didn’t hear back from the celebrity scientist, who died in 1996. And, with the passage of time, the memory of what, exactly, I had written to my hero had become as hazy as the surface of Titan (Saturn’s largest moon, about which Sagan advanced theories later proved to be true).

Then, last year, the letter resurfaced in an unexpected and extraordinary way.

One day while working at home, I received a message on Facebook from a young woman who said that she was a senior at Yale working on a thesis about Sagan and Cosmos.

She had been in Washington, D.C., at the Library of Congress, which in 2012 took possession of nearly 800 boxes filled with documents — more than 500,000 items, including letters, journals, photographs, book drafts and more — that Sagan had collected during his lifetime.

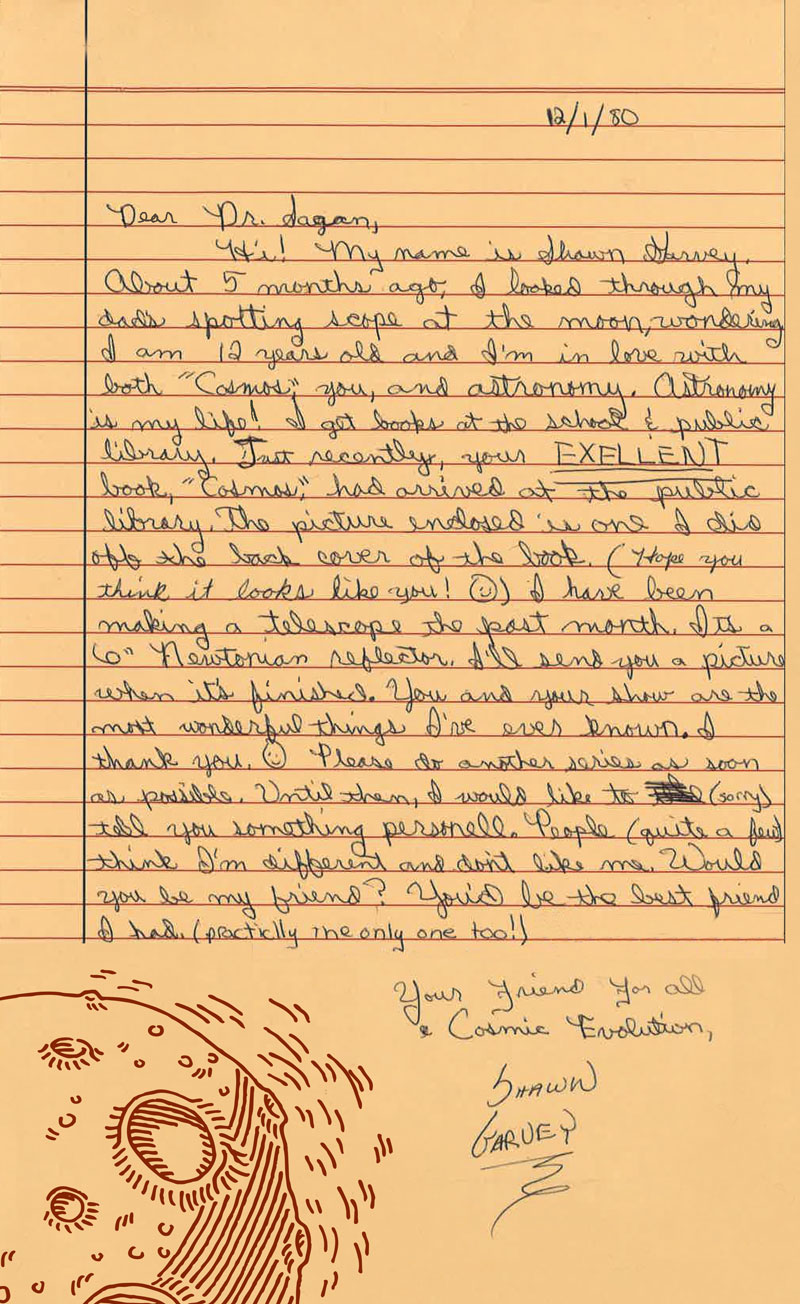

Among Sagan’s correspondence, the young woman had happened upon a fan letter from a 12-year-old boy named Shawn Garvey. She wanted to know if I was the same Shawn Garvey whose words covering two sheets of lined notebook paper had made her cry in the documents room.

Astounded, I confirmed that I was, indeed, the writer. But why, I wondered, had a preteen boy’s fan letter made her cry? I asked her to kindly scan this childhood relic and email it to me.

Upon receiving the image, decades receded and memories rushed back. It was emotional — a little uncomfortable, perhaps — but it reminded me of who I was as a sixth-grader in Vermillion, struggling to find his way.

My spelling wasn’t perfect, but my penmanship was as neat as my capabilities allowed. I gushed to Sagan about being a fan of his and of Cosmos. (“You and your show are the most wonderful things I’ve ever known.”) Then I veered into “something personell.” Or, as I would spell it today, something “personal.”

“People (quite a few) think I’m different and don’t like me,” I wrote. “Would you be my friend? You’d be the best friend I had (practically the only one, too!)”

I had absolutely no memory of writing a letter so raw to a stranger. Perhaps it speaks to Sagan’s relatability that I felt as though I could confide in him. Certainly, I remembered having those feelings throughout much of middle school. Sitting in the garage reading the words of a younger me, I thought about my own sons.

I don’t know why Sagan kept the letter (and an accompanying pencil portrait I created using a photograph from a Cosmos book jacket as a reference). But it’s a blessing to have it back after so many years.

Now, when my boys come home from school and describe their struggles — the same struggles that most middle-schoolers experience — I can share with them a letter showing that I experienced the same anxieties at their age.

Used as a teaching tool, the letter demonstrates that there is a future reality in which things do, in fact, get better. We can grow into lives that we couldn’t have imagined when we were in the throes of adolescence and experiencing the discomfort, fear, insecurity and uncertainty that comes with growing up.

The person my sons see today is Daddy — a grown man who is blessed with a loving family. He pastors a historic church in a beautiful city located conveniently near Disney World. He doesn’t need much persuasion to play the guitar and sing in front of an audience.

Now, though, they can also know the Daddy who existed long before he was Daddy to them. They can know the 12-year-old boy who often felt alone, but found joy in the grand mysteries of the cosmos and the scientist from Cornell who made him feel connected to it all.

Shawn Garvey is the senior minister at the First Congregational Church of Winter Park.