My family’s first night in Winter Park, 52 years ago this summer, was at a Holiday Inn at the corner of Lee Road and U.S. 17-92. The furniture for our house in Dommerich Estates hadn’t arrive yet, so we checked in and dined at Lum’s, a hot dog chain across the street, where Boston Market now stands.

The three-year-old Winter Park Mall — only the fourth air-conditioned indoor mall in Florida, anchored by J.C. Penny’s and Ivey’s — was across the street. Even more than a half-century ago, I don’t recall that stretch of U.S. 17-92 being called the Million-Dollar Mile very often.

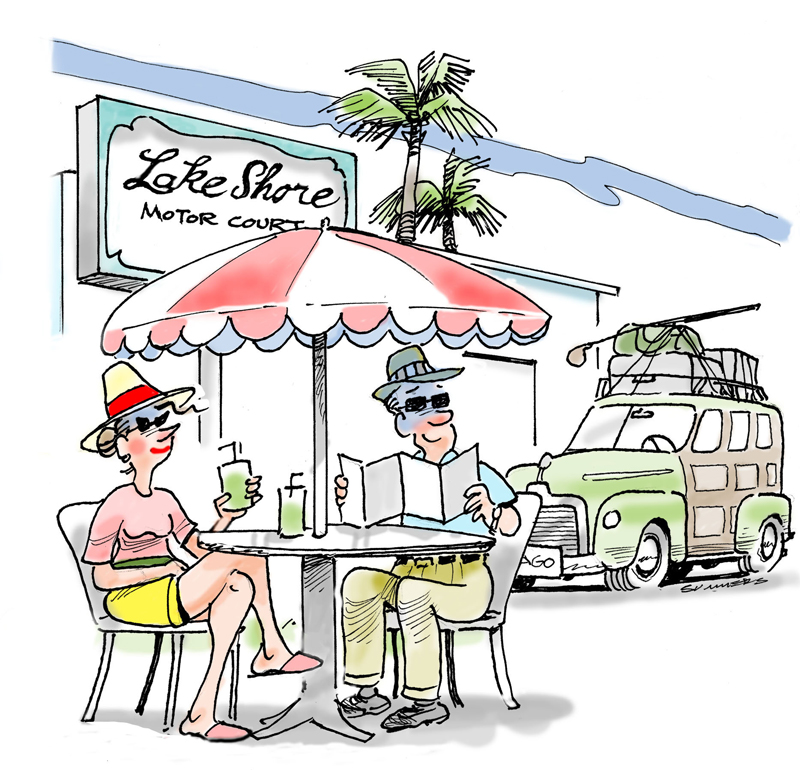

But in the 1930s and 1940s, middle-class families were flocking to more modest accommodations — including dozens of tourist cottages — along the stretch of highway that now boasts Trader Joe’s and dozens of other upscale shopping centers, some of which back up to a well-hidden Lake Killarney.

And by the 1950s, Winter Park was home to the swank and swinging Langford Resort Hotel, where the Empire Room supper club epitomized Rat Pack culture.

So it was a stroll down Memory Lane, if not the Million-Dollar Mile, when I visited the Winter Park History Museum to conduct interviews for an in-depth story on its current exhibition, Wish You Were Here: The Hotels & Motels of Winter Park. It runs through March of 2020, and the story runs in the next issue of Winter Park Magazine.

The cozy museum space, tucked into the old depot where the Farmers’ Market is now held — is packed with sometimes-kitschy ephemera from the city’s classic motels — including a re-created 1950s-style guest room using authentic furnishings, right down to the matchbooks and the Gideon Bible in the end-table drawer.

Also examined are the luxurious resort hotels that attracted monied Northerners to Winter Park in the late 1880s. There’s even a re-imagined Victorian-era children’s playroom of the sort where guests of the posh Seminole Hotel or Alabama Hotel might have stashed their youngsters while they were out boating.

A nostalgic highlight of the exhibition is the original piano from the Empire Room as well as the hotel’s poolside bar from which untold gallons of tropical drinks were served. And take time to read the wall panels, which are dense with vintage photographs and meticulously researched descriptions.

Linda Kulmann, the museum’s archivist and past board president, wrote the panels, which range from histories of early boarding houses to a locator map of mom-and-pop motels once located along the Million-Dollar Mile.

“There was a lively cultural and arts scene that seemed to attract people here,” says Kulmann when asked why visitors would choose a small inland city instead of heading to the beach. “But also, families from up north built long-term relationships with the motel owners and just kept coming back. Some of it was probably familiarity.”

Susan Skolfield, the museum’s executive director, says artifacts on display for the exhibition were donated or loaned. The Langford piano, for example, was loaned by the family that purchased it at auction when the hotel closed.

“Because our space is small, every item must mean something,” adds Skolfield, who says more than 20 volunteers began scouting for materials a year in advance of the exhibition’s opening. “We’re always creating as we go along.”

Kudos all around. The exhibition is wonderful and reinforces my impression that the Winter Park History Museum does more with fewer resources — the considerable talents of Skolfield and the museum’s legion of volunteers notwithstanding — than just about any organization in town.

Individually owned motels became cookie-cutter corporate properties designed to resemble downtown hotels. Holiday Inn, where we stayed decades ago, was an early example of such a franchise. Quality standards may have become more predictable, but the quirky charm of motel architecture from the 1920s through the 1950s was lost forever.

The Langford, located at the corner of New England and Interlachen avenues, was closed in 2000 and demolished in 2003. The upscale Alfond Inn, developed by Rollins College, now occupies this choice real estate.

These developments, along with the construction of Interstate 4 and the arrival of Disney World — which spurred construction of countless hotels on and around the attraction — led to the decline and, by the 1990s, the demise of motor courts along U.S. Highway 17-92.

“The small, family-owned motels, where friends meet on vacations and return year after year to the same kitchenettes and swimming pools, may soon go the way of downtown grocery stores and 35-cent gas,” wrote the Orlando Sentinel in 1979. “For the remaining ‘ma and pa’ motels along U.S. Highway 17-92 in Winter Park, the future appears bleak.”

When the iconic Mount Vernon Inn (110 South Orlando Avenue) was razed in 2015, Winter Park lost the last remnant of motel culture along the Million-Dollar Mile.

Today, the seven-figure moniker is more appropriate, although the dollar amount would need to increase by orders of magnitude to remain accurate. But Wish You Were Here does what the museum does best — it picks important but often-overlooked aspects of the city’s history and tells it like it was.

For a place that bills itself as the City of Culture and Heritage, the City of Winter Park’s support of the “heritage” part of the equation is minimal. Luckily, we have visionary people — we’ve always had people like that — who make certain we remember that Winter Park has always been special.

Although growth and change are inevitable, reminders of days gone by, like Wish You Were Here, are reminders that it’s up to us to keep it that way.

Randy Noles,

CEO/Editor/Publisher

randyn@winterparkpublishing.com