If Gail Sinclair and Ernest Hemingway had been contemporaries, it’s doubtful that the pair would have hung out much together. Sinclair, executive director of the Winter Park Institute at Rollins College, is a sweet-natured, soft-spoken scholar who loves analyzing literature and contemplating nature.

Hemingway, of course, was a hard-driving, hard-drinking, larger-than-life alpha male who hunted big game on the savannah, cheered toreadors as they slaughtered bulls, rushed to war zones and pummeled opponents senseless in boxing matches.

But Papa’s internal demons won the final bout in 1961, when the writer of The Sun Also Rises.(1926), A Farewell to Arms (1929), For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940) and The Old Man and the Sea (1951) blew his brains out with a double-barreled shotgun.

Sinclair is among the most respected Hemingway experts in the U.S., having notched seemingly countless publications and presentations about the iconic author. She’s also a longtime officer in the Ernest Hemingway Society and Foundation and is on the editorial board of The Hemingway Review.

You can imagine, then, Sinclair’s excitement when she discovered that Carol Hemingway, Ernest’s youngest sister, had attended Rollins from 1930 through 1932.

Sinclair learned about the connection at a 2002 Hemingway Society conference in Stresa, Italy, where she sat in on a presentation by Donald Junkins from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Junkins showed a videotaped interview with Carol Hemingway Gardner — who at age 91 was the author’s only surviving sibling.

“During the interview she mentioned Rollins twice,” recalls Sinclair, who had been a visiting assistant professor of literature at the college for two years. “As soon as I got back, I got her address from the alumni office and wrote her, asking if we could speak.”

Sinclair heard back from Gardner’s daughter, who said that her mother was willing to be interviewed. Within two weeks, Sinclair boarded a flight to Hartford, Connecticut — the nearest city with an airport — and drove for an hour and a half to historic Sheffield, Massachusetts, in Berkshire County.

“I called Mrs. Gardner’s home and told her who I was and that I wanted to confirm our meeting,” recalls Sinclair. “She was very polite and said, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, but I couldn’t possibly meet with you. I already have an appointment.’ For a minute I thought the trip had been for naught. But I realized that the appointment she was referring to was with me.”

Sinclair spent several hours with Gardner — who had not seen or spoken to her famous brother since a nasty falling out in 1932 — and found the retired schoolteacher to be hospitable but content to live outside the spotlight.

Few in Sheffield even knew that Gardner’s maiden name was Hemingway.

“She did have very fond memories of Rollins,” says Sinclair, who gave Gardner a book about the college’s history. Shortly following the interview, Gardner broke a hip and her health declined rapidly. She died just weeks later.

Sinclair later filled in the details about young Carol’s tumultuous time at Rollins — and her irrevocable split with Ernest — through private correspondence and archival records.

TUMULTUOUS TERM

Carol attended college in Winter Park so she could more easily visit Ernest, who had a home in Key West. Ernest, 12 years Carol’s senior, had become her legal guardian following the suicide of their father, a physician, in Oak Park, Illinois.

A free spirit not unlike her brother, Carol’s unconventional behavior apparently raised eyebrows right away. Sympathetic English professor Kathleen Sproul was concerned enough to write President Hamilton Holt, who was traveling at the time.

Sproul — whose detective novels included Death and the Professors — lamented to Holt that “certain influential people” considered Carol to be an undesirable sort of student.

“Colleges for many years have done their best to strangle the creative mind and to set up taboos about the individual who can’t help being different from the run of society,” she wrote. “That difference is precious! Rollins, which can be a very great college, ought to try to conserve the greatness of her students.”

Replied Holt: “Don’t worry about Carol Hemingway. It is good that we have clashes of opinion at Rollins provided it does not lead to factional animosities. I like the girl, and if you find that some people are trying to depress her, do your share to express her, or get her to express herself, which is better.”

What prompted Sproul’s adamant defense is unknown. But Carol would soon give the campus plenty to have clashes of opinion about.

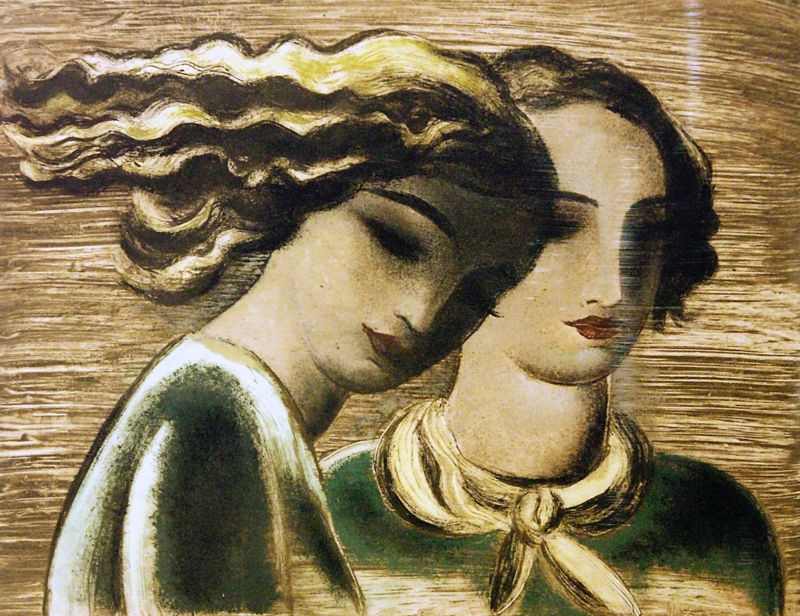

In 1931 she wrote “The Girls” for The Flamingo, a student literary magazine. The 600-word short story — deftly told using the terse but multilayered language popularized by her brother — seemed to imply a same-sex romantic relationship between two androgynously named friends, Lou and Glen.

However, it was Carol’s torrid relationship with John “Jack” Fentress Gardner, who had transferred to Rollins from Princeton, that rankled college officials and caused her famous older brother — no shrinking violet — to become uncharacteristically prudish.

Complicating matters, Carol and Jack appear to have cohabitated in Lakeside Cottage, a campus dormitory. When this transgression became known in late 1932, Carol left Winter Park for Vienna, Austria, where Jack joined her in early 1933.

PRUDISH PAPA

Ernest despised Jack — though he may well have despised any suitor — and sent his sister scathing and hurtful letters, one of which accused her, without evidence, of saving money for an abortion.

That Hemingway behaved like a jackass isn’t shocking — he was often cruel to those closest to him — but the depth of his vitriol toward his cherished youngest sister remains jarring today. The siblings never again communicated.

Jack and Carol were married in 1933 and tried to re-enroll at Rollins as a couple. But Holt — who positioned himself as a progressive but often behaved as a patriarch — was having none of it. In a memo to Dean Winslow Anderson he wrote:

“I don’t think we should let Jack Gardner and Carol come back even if they pay the full tuition. … I think the thing to do is write Carol and her husband why we cannot take them back, namely, that we had direct evidence that they were living together in Lakeside [a college dormatory] before they left.”

Nevertheless, despite Holt and Hemingway, love prevailed over long odds.

Jack became an author and educator who wrote about spiritualism, transcendentalism and anthroposophy (a philosophy based upon Austrian esotericist Rudolf Steiner’s belief that an objective, intellectually comprehensible spiritual world exists.)

He was the longtime headmaster of the Waldorf School of Garden City on New York’s Long Island. Waldorf schools — which use curricula based upon Steiner’s theories of child development — seek to develop intellectual, artistic and practical skills while cultivating imagination and creativity.

John “Jack” Fentress Gardner died in 1998. He and Carol Hemingway Gardner — who didn’t attend her brother’s funeral and, sadly given her obvious aptitude, never wrote for publication again — were married for 65 years.

Quite a story, all right. It might have been written as a work of fiction by Hemingway or perhaps F. Scott Fitzgerald, another Lost Generation icon about whom Sinclair has academic expertise. She serves on the board of directors of the F. Scott Fitzgerald Society.

SCHOLARLY SLEUTH

Hemingway and Fitzgerald make rarified company for a girl born in rural Wisconsin to parents who didn’t graduate from high school. But Sinclair, always a voracious learner, earned an undergraduate degree in education and a master’s degree in English from the University of Missouri Kansas City.

In 1977 she married her high-school sweetheart, an ambitious young conductor named John Sinclair. “My first date with John was a blind date,” she recalls. “I remember thinking, ‘This guy is going to go places, and I want to go, too.’”

Luckily, they didn’t have to go too many places before putting down roots in Winter Park. In 1985, after a stop at East Texas Baptist University, John was named chair of the department of music at Rollins. In 1990 he also became artistic director of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park.

The Sinclairs share a fierce Midwestern work ethic. While John became one of the region’s most high-profile arts personalities, Gail taught American literature at Boone High School and earned a Ph.D. in English from the University of South Florida in Tampa.

She commuted to classes — a 180-mile round trip. “That was before cellphones,” she says. “I considered that drive to be my night off.”

In 2007, after years as an adjunct and a visiting assistant professor, she was named executive director of the Winter Park Institute at Rollins College, which runs a popular speaker series. She also teaches in the college’s Master of Liberal Studies program.

Sinclair — whose favorite books are To Kill a Mockingbird and The Great Gatsby — has a professorial demeanor but is also self-deprecating and wryly funny. She’s proud of her Ph.D. but recognizes that great literature and classical music are thought by some to be superfluous — and even a bit snooty.

The couple’s young niece, for example, once told her teacher that her aunt and uncle were doctors and might be able talk about their work with the class during Career Day.

Recalls Sinclair: “The teacher asked what kind of doctors we were, and after thinking about it for a moment, our niece replied, ‘I don’t know, but I don’t think they’re the kind that help anybody.’”

It’s true, Sinclair says, that reading a good book isn’t likely to cure cancer. But that doesn’t mean literature — and, of course, music — isn’t crucial to societal health.

Adds Sinclair: “John and I comfort ourselves by educating young men and women, many of whom will be significant in concrete ways — the change makers and helpers, as Fred Rogers would say.” (The Sinclairs were close to the beloved Rogers, a 1953 Rollins graduate known worldwide for Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.)

“But we also know that the arts are a necessary influence in history’s great civilizations — and music and literature are key elements in that realm,” she adds. “This may be an exalted way of justifying what we do for a living. But like medicine’s creed, we at least do no harm, and hopefully we provide some benefit.”

TWO GIRLS

BY CAROL HEMINGWAY

They sat on the third-floor fire escape of the dormitory and let their legs hang over the edge. Lou, slim-shouldered, hunched over her cigarette, and Glen leaned on one elbow and swung first one leg then the other with a slow rhythm. With large shallow eyes she watched Lou.

“The way you smoke is killing,” she said. You’re pretending to inhale. Don’t just hold the smoke in your mouth; draw some in and then let it out slowly,”

Lou still stared at the lake, puffed with a violent intake of breath, and started coughing. Glen didn’t laugh.

“I don’t care if I do look silly. Inhaling is bad for you anyway.”

“Listen. How do you ever expect to enjoy smoking if you don’t do it properly? You’re always talking about enjoying life. You’re a funny one. I’m not trying to kill you.”

Lou obediently tried again.

“I do want to enjoy things,” she said. “I want to enjoy everything in the whole world. I’ve been enjoying the lake.” She looked out over the water. “This morning there was a faint mist on it like the delicate film left by breath on a mirror. This afternoon I loved it. The steady sun made it look warm as a silent friendly companion. Last night it was —”

“Gosh, don’t start raving about the lake last night. I was out canoeing with that beast. There was just too damn much of your lake last night. I didn’t think I’d ever get home.” Glen lay back, pulled her knees up, and braced her heels against the edge of the platform.

“But Glen, didn’t you notice last night how the lake seemed to leer. It was repulsive as a cesspool. The stars were cool and disinterested, and there was a languid, insulting-sort-of breeze. I guess I just imagined a lot of things, sitting here by myself. I felt so very much alone.”

“You sweet kid. But for hell sake don’t get pensive. I’m not in the mood for pensiveness. Lighting another cigarette, she said “I wish I had a horse down here. I’d like to take him out in a gallop down all the long straight roads I could find.”

She stood up, looked down at Lou, and then far past her. There was a silence.

“Listen,” she stated with decision. “I’ve heard people say there’s something funny between us. It’s not good to have stories like that going around.” She looked down at Lou. “Because there isn’t anything, is there?”

Lou looked up at her cigarette and then continued to gaze at the water. She flicked her cigarette away.

“I wish I could see where the falling stars land,” she said, looking at the bright tip glowing on the ground. “I’m so tired. I don’t think I’ll be able to sleep. I’m going to stay here. You can go in if you want to,” She was still watching the ground. She quivered slightly.

“It’s funny the way you can’t get away from yourself in the dark,” she went on. “It’s much easier to hide in the light. In the dark real fears take advantage.”

“Look out. You’ll be quoting in a minute.”

There was a violent convulsion of Lou’s body. Glen grabbed her around the waist.

“Say, you came near falling off,” Glen said.

“I’m a little dizzy, I guess.” She relaxed a little in Glen’s strong circle of arms.

“Poor little kid,” said Glen. “I’ll carry you in to bed.”