When Winter Park Publishing Company LLC moved its offices last year, we found ourselves occupying a building in which I had worked 35 years before — for perhaps the most interesting and impactful small business that ever hung out a shingle in this town.

If memory serves, although the interior of 201 West Canton Avenue has been reconfigured, I’m now sitting in the former office of my erstwhile boss — a man whom I count as a personal hero, and whose philosophy has for decades guided how I approach work.

The business was Philip Crosby Associates (PCA). In the company’s heyday, when major American manufacturers were fighting to overcome the perception — the reality, in fact — that their products were inferior to those made overseas, it was Crosby, an internationally known business philosopher, whose guidance was sought by beleaguered executives.

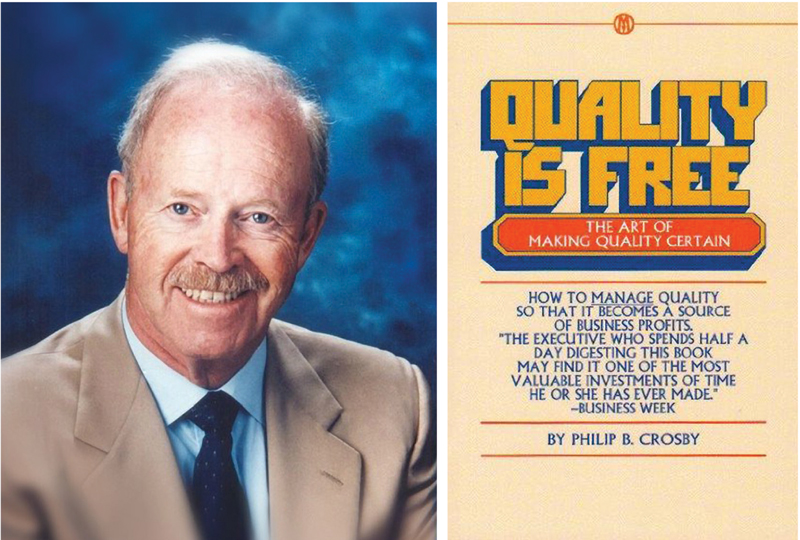

Each week, hundreds of corporate bigwigs from around the country — and around the world — traveled to Winter Park to attend Crosby’s “Quality College” for five days of lectures from and discussions with the man who had written the 1979 business bestseller Quality is Free and had invented the concept of “zero defects” in manufacturing.

Crosby was entertaining and inspirational — although he despised comparisons to motivational speakers. One trade publication described him as “the fun uncle of the quality revolution,” which was a clever if incomplete descriptor. This fun uncle had been worldwide vice president for quality at ITT.

As PCA grew, and bright young acolytes were trained to teach his concepts, Crosby began holding impromptu confabs with Quality College attendees, for whom he was something of a rock star. “Quality can’t be controlled,” Crosby would proclaim. “It has to be caused, starting at the top.”

This was important stuff for American industry. But it was also important for Winter Park. First, it showcased the city to countless influencers, many of whom undoubtedly returned for more leisurely visits with their families.

Every day, Quality College attendees lunched en masse at Park Avenue restaurants. Rooms at the Mount Vernon Inn were booked solid for months in advance. Crosby — who looked like Teddy Roosevelt in a power suit — lavished patronage on hundreds of local vendors, all of whom were proud to be selected by a company synonymous with the best of everything.

Of course, the word “quality” meant something different to Crosby than it did to most of us. To him, quality meant simply conformance to requirements — whatever those requirements might be. A Chevette that met all the requirements of a Chevette was every bit as much a quality car as a Cadillac that met all the requirements of a Cadillac.

Further, he preached, it was always cheaper to “do it right the first time” than to assume, as most American companies did, that errors would invariably occur. The expense of implementing a zero-defects policy would always be recouped, he contended, by eliminating waste and do-overs.

PCA eventually came to employ some 300 people, all of them well paid and even pampered. Top executives drove company Cadillacs (General Motors was a major client) and everyone from the custodian to the COO believed that they were performing both a job and a patriotic service.

But, when I joined, PCA hadn’t yet reached those heights. I had written a story about Crosby for a local newspaper, and he seemed impressed that I appeared to understand his message. Would I be interested in coming to work for him and starting a company newspaper?

Not a newsletter, he emphasized. A real weekly newspaper, like a small city would have, with stories about the company and its people. I thought about it — for about 10 seconds. A few weeks later, I was editor of This Week at PCA — a tabloid with an initial press run of about 45 copies. The boss even gave me a nickname: “Scoop.”

PCA had a remarkable run, surviving economic downturns and flavor-of-the-month management trends. But it couldn’t survive Alexander Proudfoot PLC, a U.K.-based consultancy that bought the company in 1989 and ran it into the ground.

Crosby rescued the company’s remnants in 1997. But he died at age 75 in 2001, before he could complete his reclamation project.

There’s still a Philip Crosby Associates in Boston, but the latest iteration seemingly has no website and several calls succeeded only in reaching an automated voicemail service.

I like to think Phil would enjoy Winter Park Magazine. I expect he would appreciate the fact we strive (not always successfully) to eliminate defects and do it right the first time.

Randy Noles

CEO/Editor/Publisher

randyn@winterparkpublishing.com