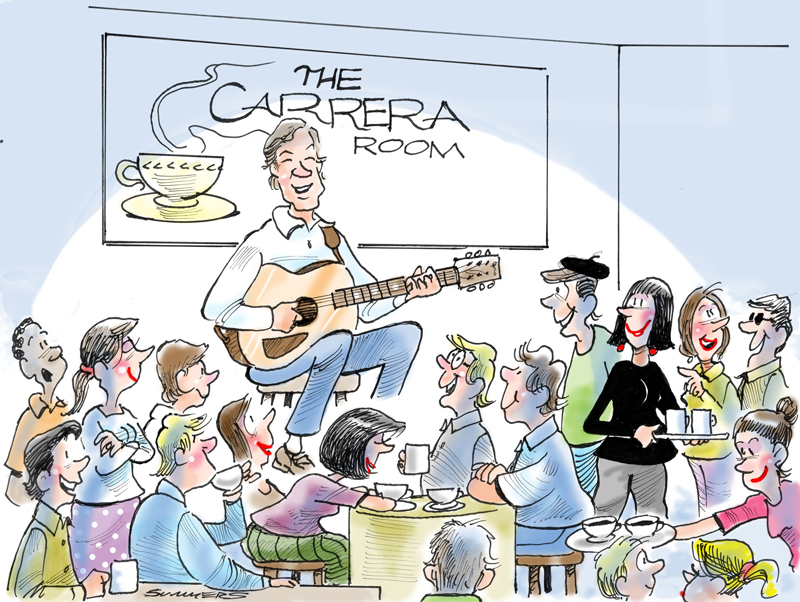

Pete and Barbara Hodgin came up with an idea to draw nighttime crowds to their eatery at 534 South Park Avenue. The cool kids were listening to folk music in the early ’60s. Hippies hadn’t yet supplanted beatniks and the British Invasion was yet to come.

So, on Fridays and Saturdays from 9 p.m. to 1 a.m., Hodgin’s Restaurant — which served breakfast, lunch and dinner seven days a week — morphed into the Carrera Room, a coffeehouse for young folkies.

“There was a hard-core folk scene here in those days,” says Chip Weston, a Winter Park artist and entrepreneur who was a student at Rollins College from 1966 through 1970 and played guitar with a band called the Drambouies. “Around purists, you didn’t dare play anything other than folk music.”

The Carrera Room was a walkable distance from Gamble and Maggie Rogers’ home on Knowles Avenue. The scene naturally attracted Rogers, who had run his own short-lived coffeehouse, the Baffled Knight, in Tallahassee.

His partner in that venture was Paul Champion, an Earl Scruggs protégé who would go on to become a bluegrass legend in his own right.

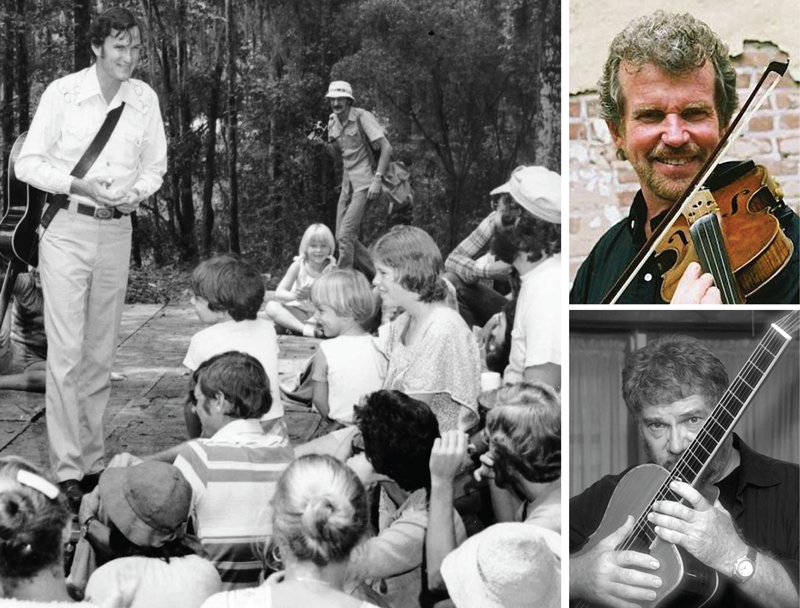

“We just wanted to see Gamble because he was such a good picker and singer,” recalls Gainesville-based musician Alan Stowell, who has toured with such stars as Don McLean and Maria Muldaur, often playing fiddle as well as guitar.

Stowell credits Rogers with igniting his passion for the guitar starting at the Carrera Room. But the music didn’t necessarily end at 1 a.m.

“We’d go to Gamble’s house and have sessions,” adds Stowell. “It was great.” In those days Stowell and his jug band would rehearse in Central Park, just blocks away from the Carrera Room. In time, Rogers would find his way over to see what they were doing. “Off stage he was very generous,” Stowell said. “Gamble was very supportive of other musicians.”

Indeed, Rogers found plenty to support in his hometown: “There’s more good guitar players in Winter Park than any place I’ve ever been,” he once stated after having achieved a measure of national fame.

When Park Avenue rent got too high, the Hodgins moved their operation to 643 North Orange Avenue, just west of Rollins College. That’s where the new and expanded Carrera Room was born.

In a 1967 interview with the Orlando Sentinel, Barbara Hodgin called the young people who gathered to listen to local and touring folk singers “the best bunch of kids in the area.”

One of the locals was Jeanie Fitchen. She was just 14 when Barbara Hodgin gave her a chance to perform — and to get paid for it.

“Barbara often hired me at $8 a night to host open-mic night,” recalls Fitchen, who today lives in Cocoa and continues to perform at folk festivals. “Little did she know I would have gladly paid her to let me sing on that tiny stage.”

On those music-filled Fridays and Saturdays, the Carrera Room offered a wide variety of coffee, tea and frappes costing from 40 to 65 cents. Gracing the menu were drawings of important and controversial folk artists of the day: Joan Baez, Charles White and Pete Seeger.

In time, the Carrera Room became known as a place to see important national acts passing through town such as Fred Neil, a mainstay of the Greenwich Village folk scene and writer of such hits as “Candy Man” for Roy Orbison.

When Lakeland guitarist Rick Norcross decided to open his own coffeehouse near the campus of Florida Southern College, where he was a student, he called it the “Other Room.”

“I named it as an alternative local version of — and in honor of — the Carrera Room in Winter Park,” says Norcross, who now tours New England with a popular Western swing band, Rick & the Ramblers.

“Certainly, it was tongue in cheek,” he adds. “But it was also named out of respect for the position that the Carrera Room held in the hearts of aspiring folk singers in the early 1960s.”

One of those aspiring folk singers would go on to become the godfather of country rock. His name was Gram Parsons, a Winter Haven native who performed at the Carrera Room with his folk quartet, the Shilos.

And there were others. Bernie Leadon, then just age 17, impressed Carrera Room patrons with his banjo prowess. Within a few years Leadon was playing alongside Parsons and Chris Hillman in the Flying Burrito Brothers. He later co-founded ’70s rock supergroup the Eagles.

By this time, Rogers had become a mainstay at the Carrera Room and other local venues, such as the Beef & Bottle on Park Avenue and Dubsdread Country Club in Orlando. A hometown folkie hero, he always performed before packed houses.

Rogers’ repertoire included such songs as “Deep River Blues” and “Two Little Boys.” Instrumentals included “Cannonball Rag,” written by Merle Travis, his musical hero and the man whose guitar style he emulated.

Rogers — who by now had begun to attract attention in Greenwich Village folk circles and hung with the likes of Phil Ochs and Bob Dylan —worked to bring big-name national acts to Winter Park.

In the summer of ’65, Stowell accompanied Rogers to Rollins, where the pair persuaded administrators to sponsor a Carrera Room concert by all-time banjo great Don Reno and his Tennessee Cut-ups. The band barely fit on the venue’s tiny stage.

Reno, who went on to compose 500 songs and be inducted into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame, was perhaps the biggest name to headline the Carrera Room. “I was on the edge of my seat all night,” Stowell recalls.

After the show, the group headed to Rogers’ house, where the jam session lasted well into the wee hours. Rogers wanted to encourage Stowell and asked him to perform a song for Reno and his sidemen.

“Alan, play Cleopatra’s Caravan for Don,” Rogers urged his friend. Stowell obliged — and to this day feels embarrassed by the version he delivered. “Don was nice and complimented me,” he says.

Despite the coming of the Beatles and an invasion of electrified singer-songwriters both British and American, the Carrera Room, like the Flick and the Gaslight South coffeehouses in Miami, remained folk genre strongholds well into the late ’60s.

Mount Dora musician, writer and comedian Jim Carlton came into Rogers’ expansive orbit in 1967.

“Gamble was a big deal locally even then,” says Carlton, who began his music career in 1962 with Parsons and Jim Stafford in a rock band called The Legends. “He had such a likeable personality and was beginning to make a name for himself.”

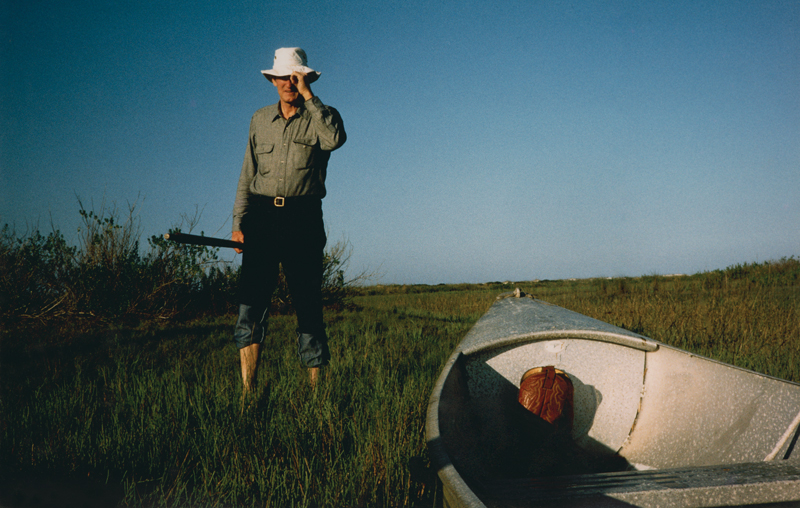

Carlton says Rogers never obsessed over achieving major commercial success, choosing instead to develop and refine his nuanced, drawn-out tales of Florida rogues and backwater haunts.

“Gamble and I would get on the phone and talk for hours,” says Carlton. “He had a vintage Martin guitar but made me promise not to tell him what it was worth.”

Most musicians, it seems, would want to know such information — for insurance purposes, if nothing else. Rogers, however, was not most musicians. “I’m not a collector,” he explained to Carlton. “For me, it’s a tool — and that’s its real value.”

The Carrera Room — and the restaurant that anchored it — closed in 1970. For most longtime locals, it has faded in time like much of greater Orlando’s pre-Disney history. But not for performers who still ply their trade, such as Stowell, Fitchen, Norcross and Carlton.

Rogers, too, lives on in the memories of fans, friends and family. So, too, do the memories of such Florida folk icons as Paul Champion, Will McLean and Jim Ballew. They made their mark in a bygone era when live music was everywhere.

“Gamble was just special,” recalls Weston. “There were a lot of us who didn’t know if we were going to make our careers in music or not. But we knew Gamble was the real deal.”

Weston recalls taking a girlfriend to one of Rogers’ shows. She professed to dislike folk music and went along only grudgingly. “She ended up loving it,” says Weston. “Gamble had such magnetism. If you gave him five seconds, he had you.”

AN UNCOMPROMISED LIFE

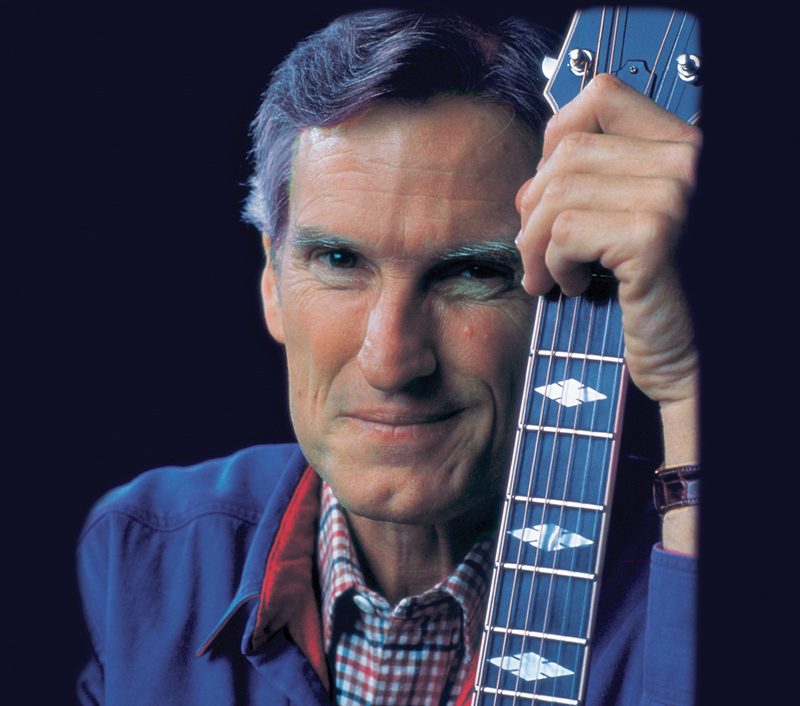

One sentence sums up the character of Winter Park native James Gamble Rogers IV, the Florida troubadour who died trying to save a drowning tourist whom he didn’t know: “He was interested enough in strangers to give his life for one.”

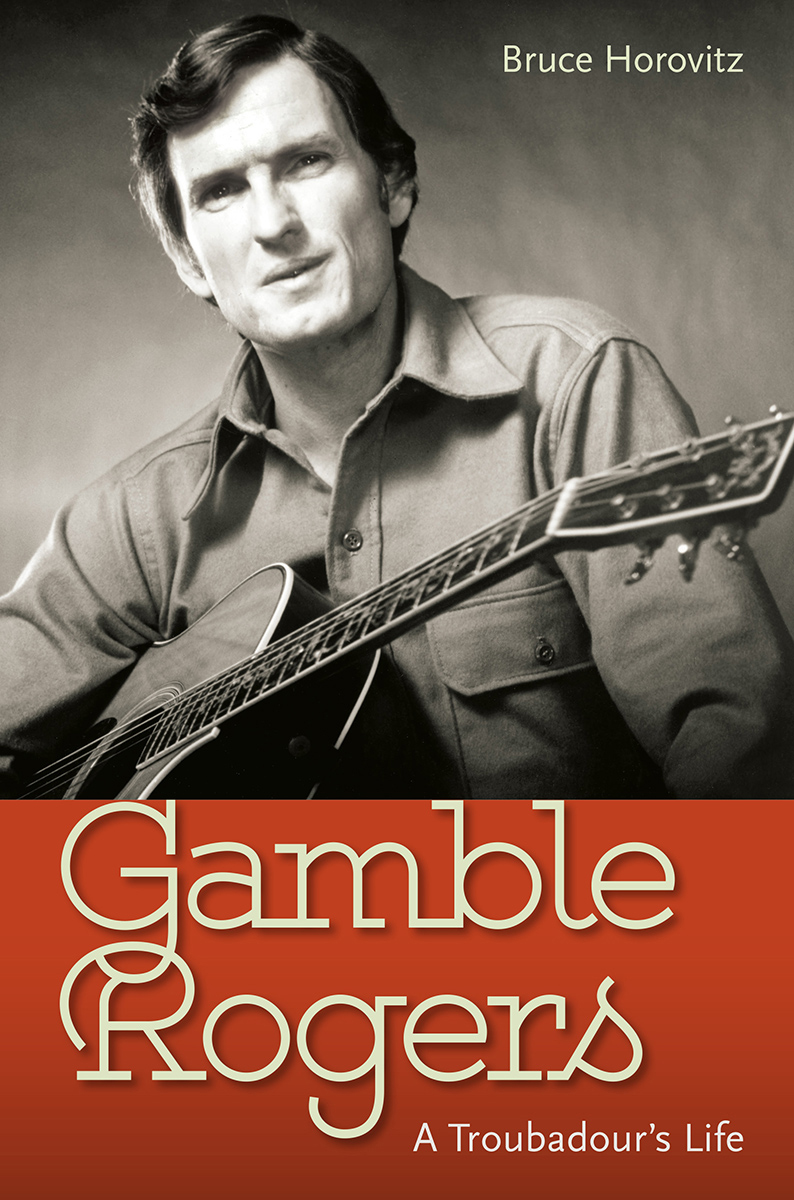

That’s one of many poignant quotes in Bruce Horovitz’s breezy new biography, Gamble Rogers: A Troubadour’s Life (University of Florida Press).

A biography of this authentically Floridian singer and storyteller — known early in his career as “Jimmy” Rogers — is long overdue. And Horovitz’s work is an easy-to-digest introduction to the man who was considered by many to be Florida’s unofficial musical ambassador.

Still, completionists who hold Rogers in high esteem to this day may not find A Troubadour’s Life — which can be read in a sitting or two — dense enough to sum up the life and career of a bona fide legend.

Then again, it would take several volumes to really do the subject justice.

You need not enjoy folk music or tall tales to admire Rogers, who was the eldest son of renowned local architect James Gamble Rogers II. He died a hero in 1991, in the rough surf near his beloved St. Augustine, trying to rescue a total stranger flailing in the Atlantic Ocean undertow.

Rogers, 54, didn’t swim well, and a chronic spinal malady all but ensured that his charge into the raging ocean on an inflatable raft would be a suicide mission. No matter, friends say. The sight of a drowning man and his young daughter screaming for help left him no choice but to try.

Ordinary people mattered to Rogers. He was once approached in a parking lot by a man — yet another stranger — who asked a favor. His wife was near death from cancer and might be bolstered by even a brief visit from her favorite singer.

Rogers, never one for half measures, ended up performing a long bedside concert for an audience of two. Never mind that he’d just finished a grueling tour and was looking forward to getting home to his own wife and children.

Despite such heart-tugging stories, A Troubadour’s Life is neither maudlin nor overly sentimental — nor should it be. There’s far too much to celebrate in Rogers’ life and legacy.

He gave up what was sure to be a comfortable life pursuing a career in architecture in the footsteps of his famous father to celebrate rural Florida with whimsical stories, evocative songs and skillful guitar-picking.

For nearly 30 years, he presented a genre-defying one-man show that took him from raucous bars to intimate listening rooms to the stage of Carnegie Hall with bluegrass legend Doc Watson.

But he started in Winter Park at local coffeehouses such as the Carrera Room, located first on Park Avenue and later relocated to Orange Avenue, where The Porch restaurant and sports bar now sits.

It was the early ’60s, and from Greenwich Village to Coconut Grove, folk music was everywhere. Vanilla acts like the Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul and Mary ruled the charts. Dylan had yet to plug in, and the Beatles were unknown in the U.S.

By 1966, Rogers moved to New England to pursue an opportunity in architecture at a Boston firm. But he was waylaid by an audition in Greenwich Village, where his formidable guitar-picking skills landed him in a nationally known touring act, the Serendipity Singers.

Rogers lasted long enough to learn that ensembles didn’t suit his style. From then on, he followed his passion down a long, sometimes bumpy road of one-nighters as a spinner of folksy yarns and an influencer of more commercially successful artists such as Jimmy Buffett.

A contemporary of other Florida folk legends such as Paul Champion and Will McLean, Rogers conjured up stories from fictional Oklawaha County, and delivered them in a preacher’s cadence as delighted audiences marveled at his linguistic pyrotechnics.

In A Troubadour’s Life, the many shining sides of Rogers are emphasized. The conflicts with his family over choosing life as an artist, and the toll his peripatetic career took on his relationships, not so much.

There are also some factual errors. For example, Horovitz writes that Rogers saw Elvis Presley perform in 1953. Elvis was, in fact, driving a truck in 1953 and didn’t play Orlando until 1955. It’s a small error, but anyone who writes a book about popular music ought to know some basic Elvis history.

More significantly, Horovitz gets it wrong about ownership of the Carrera Room. It was not run by Rogers’ first wife, Maggie, as Horovitz states. It was opened as an offshoot of Hodgin’s Restaurant by Pete and Barbara Hodgin, whose invaluable contributions to the local folk scene are unmentioned.

Still, if you didn’t know of Rogers and his homespun tales, you’ll come away from this book wishing that you did.

Of course, his drawn-out orations weren’t suited for commercial radio or television. Horovitz writes that Rogers once auditioned for the Smothers Brothers but didn’t get the gig. What he did best simply couldn’t be done in two or three minutes.

Rogers received widespread exposure only through NPR, where he was a current-events commentator on All Things Considered in 1976 and 1977, and then again in 1981 and 1982. One of his monologues, “The Great Maitland Turkey Farm Massacre of 1953” was included in Susan Stamberg’s book, Every Night at Five: The Best of all Things Considered.

Although Rogers never came close to becoming a household name, he was content flying just below the radar. He toured the country in a green Mustang and held court on his home turf — the rough-and-tumble Tradewinds bar in St. Augustine.

In the aftermath of his death, the state Legislature created the Gamble Rogers Memorial State Recreation Area, a 144-acre park on Flagler Beach between the Atlantic Ocean and the Intracoastal Waterway.

St. Johns County opened Gamble Rogers Middle School near St. Augustine in 1994, and the state’s Division of Cultural Affairs named Rogers to the Florida Artists Hall of Fame in 1998.

Lately, however, some have questioned whether Rogers is well-enough-known to still have a school and state park named after him. Errors notwithstanding, Horovitz’s diligent work and dozens of primary-source interviews are more than enough to help us all gladly beg to differ.

—Bob Kealing

Bob Kealing is a musicologist and author. His most recent book is Elvis Ignited, The Rise of an Icon in Florida (University Press of Florida).