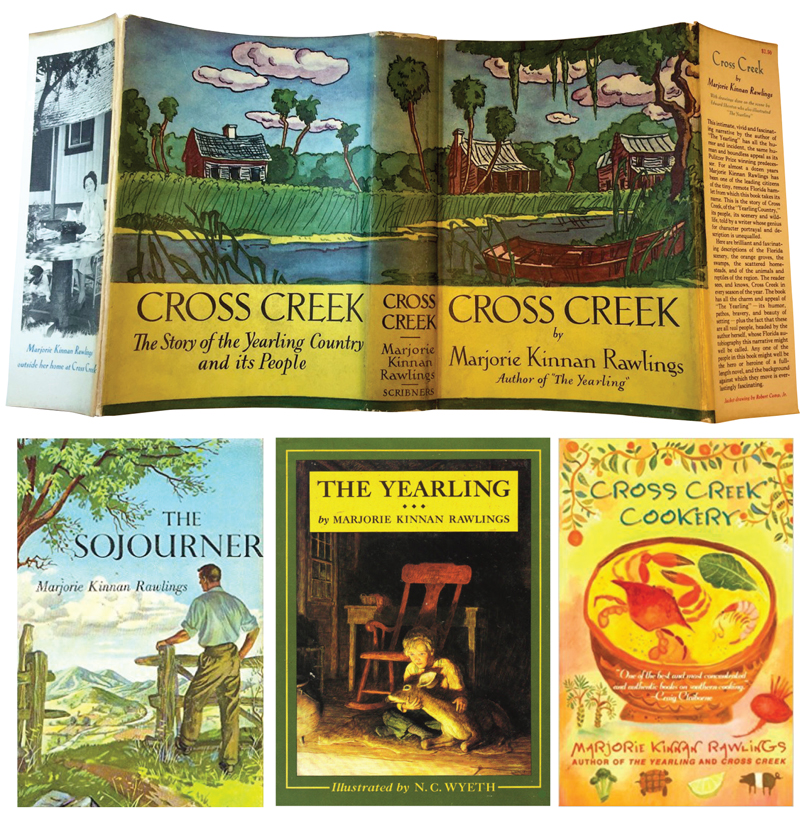

No one who reads Cross Creek can doubt that Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings had genuine affection for the quirky Crackers who inhabited the all-but-untamed north Florida outpost where she owned a ramshackle farmhouse and a 72-acre citrus grove.

But when a crotchety resident of Island Grove — a tiny hamlet near Cross Creek — sued Rawlings for $100,000 over what she correctly believed to be an unflattering depiction in the 1942 bestseller, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author’s Rollins College admirers mobilized in her defense.

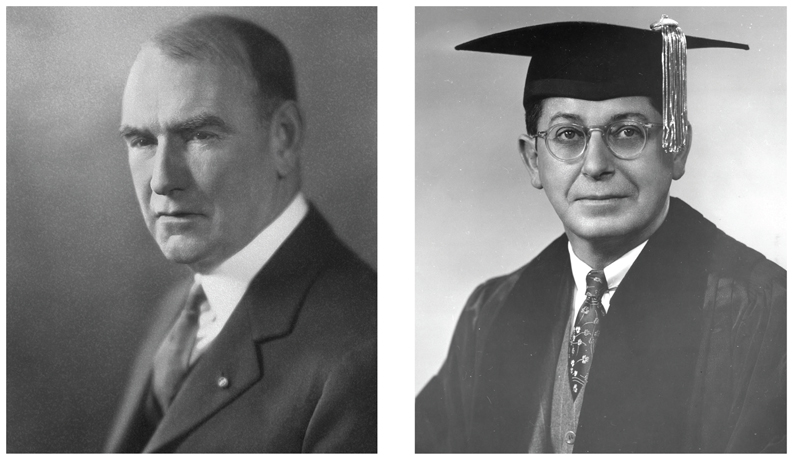

Rawlings had many connections with the Winter Park liberal arts institution, not the least of which was a friendship with legendary President Hamilton Holt and venerable Professor of History Alfred J. Hanna, who participated in the infamous lawsuit as a witness for Rawlings.

In yet another unlikely local connection, prominent Winter Park attorney Ralph V. “Terry” Hadley III was born in Island Grove and is the great-nephew of the colorful complainant — a feisty social worker named Zelma Cason.

As a child and a young man, Hadley — now a shareholder in Swann Hadley Stump Dietrich & Spears — enjoyed summer visits to his Aunt Zelma’s tin-roofed home. She took him hunting and fishing and let him tag along to her office at the Gainesville branch of the State Welfare Board. “Aunt Zelma was just fun to be around,” he recalls, adding that she “was a tough old bird who could cuss the bark off a tree.”

Hadley also met Rawlings — whom he knew as “Marge” — and describes her as a warm, down-to-earth woman who, despite her fame, was entirely unpretentious.

Cason and Rawlings had been close, until the publication of Cross Creek soured the friendship and led to a colorful courtroom donnybrook that ultimately established an important precedent: that privacy was a right in the State of Florida.

Hadley’s first encounter with Rawlings was in 1946, when he was 4 years old. The much-publicized trial had concluded but the appellate process was underway when Hadley’s mother (and Zelma’s niece), Clare, engineered a potentially fraught meeting between the warring parties.

It happened in Crescent Beach, where the Hadley family was vacationing. Rawlings owned a cottage nearby, and Cason rented modest quarters within walking distance. But neither knew that the other had been invited by Clare to drop by.

“My mother was a peacekeeper,” says Hadley. “Everybody hated to see Marge and Aunt Zelma fighting. She was trying to be a bridge over troubled water.”

The ploy didn’t work — at least, not then.

According to Elizabeth Silverthorne, author of 1988’s Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings: Sojourner at Cross Creek, Rawlings arrived with her husband, Norton Baskin, and was surprised to find Cason and her young great-nephew already there.

Although no spontaneous fence-mending occurred and the appeal continued, everyone appears to have made the best of what was surely a tense situation.

Writes Silverthorne: “Marjorie apologized for her housecoat and Zelma apologized for her bare feet. Then they had a drink together and Zelma and Norton joined forces to tease Clare’s little Terry into eating his supper. They discussed Cason family matters, and at one point Zelma said, ‘Marge, you’d be just crazy about Terry if you knew him.’”

Later, according to Silverthorne, Rawlings described the episode to her attorney as “utterly weird.” Oblivious to the drama unfolding around him, “little Terry” finished his supper as the adults chatted politely despite bitter ongoing litigation.

Cason and Rawlings had dug in as a matter of principle. Neither was willing to back down. “Marge and Aunt Zelma were just great characters,” recalls Hadley. “That’s why when they fought, it was knock-down, drag-out.”

The courtroom clash between Rawlings — a beloved national figure — and the aggrieved but abrasive Cason was intensely personal. But it was also as entertaining a spectacle as any that ever unfolded in the sweltering Alachua County Courthouse.

And it was important. The outcome, settled only after a precedent-setting ruling by the Florida Supreme Court, has implications for writers regarding the legal pitfalls of using real people — specifically those who aren’t public figures — as characters.

More broadly, the case speaks to ethical issues around cultural appropriation. The concept was introduced in academia as a scholarly critique of colonialism. But in recent years, anti-appropriation rhetoric has been used to bludgeon everything from art to literature to clothing.

Often, such criticisms go too far. Still, it could be argued that Cross Creek is the very definition of cultural appropriation, at least as the term is understood today. Rawlings, though, would surely deny any intent to exploit — and would insist that Cracker culture was her culture, too.

Which, of course, it was — but by adoption and with plenty of built-in escape mechanisms. The author, who portrayed herself as a workaday Cross Creek denizen not unlike her backwoods neighbors, was never truly one of the people about whom she wrote so vividly.

A literary celebrity and a sophisticated, college-educated Yankee — her distaste for that descriptor, and all it implied, notwithstanding — Rawlings had won a Pulitzer Prize in 1939 for her novel The Yearling.

She could abandon hardscrabble Cross Creek any time for a posh apartment at the Castle Warden Hotel in St. Augustine, managed by her husband, or for her cozy Crescent Beach cottage.

Her neighbors were her house servants, her grove workers, her charitable beneficiaries and her hunting and fishing companions. To the extent that class and race permitted, she considered many of them to be her friends — but on an essentially transactional level.

When she entertained, her gourmet meals were savored not by the impoverished rustics who provided fodder for her lively stories but by renowned authors, erudite professors and the occasional movie star.

Although she worked her land as though her very survival was at stake and eagerly immersed herself in Creek camaraderie and contention, she remained “a kind of reportorial visitor from another planet,” contends Samuel I. Bellman in 1974’s Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, a biography that was part of a series spotlighting notable American authors.

“For all its pastoral quality, Cross Creek reflects a wider range of experience than the bucolic, or even the bucolic seen through urban eyes; there is the dimension of privilege that gives the book its particular character,” Bellman writes.

Privilege may explain why Rawlings so badly misjudged the prideful Cason.

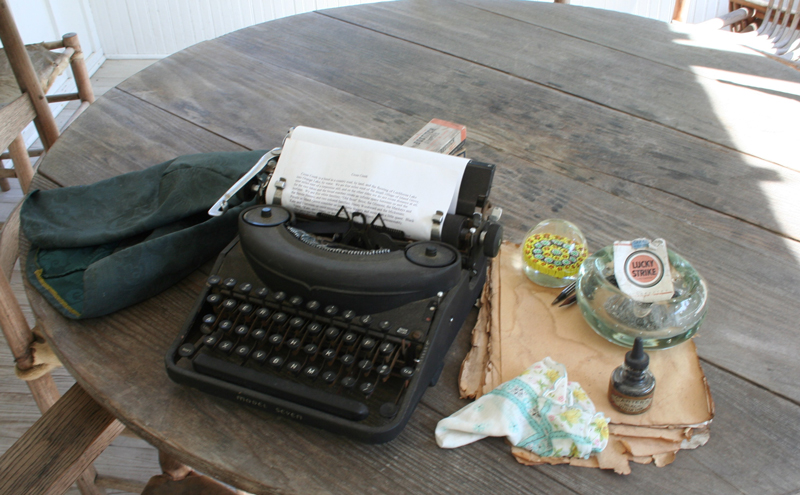

At issue was “The Census,” a chapter in Cross Creek that recounts an eventful horseback census-taking excursion upon which Rawlings accompanies Cason. They visit ramshackle homes deep in the swamps while Cason offers colorful commentary.

In “The Census,” Rawlings bluntly characterizes Cason, who would have been about 40 at the time, as “an ageless spinster resembling an angry and efficient canary … I cannot decide whether she should have been a man or a mother.”

It only gets worse: “She combines the more violent characteristics of [a man and a mother] and those who ask for or accept her manifold ministrations think nothing of being cursed loudly at the very instant of being tenderly fed, clothed, nursed or guided through their troubles.”

Although in her later testimony Rawlings would artfully, if dubiously, explain that the incendiary comments were meant to be compliments, she must surely have known that no woman in that place and time — and, indeed, few now — would consider spinster to be a term of affection, nor would they wish to be described as masculine or profane.

Ironically, either adjective could just as easily be applied to the bawdy, hard-drinking Rawlings, in whom such qualities were generally thought to be charming and eccentric.

Rawlings, it seems, had been seduced by her own celebrity, believing that a cleverly crafted insult from an author of her stature would be deemed flattering, not hurtful.

Tragically, considering the consequences, she could easily have diffused the situation, avoiding five years of needless expense and emotional exhaustion that resulted in reduced output and, arguably, early death.

Cason’s precise motives for filing the suit — apart from embarrassment — have remained a subject of speculation. Could it have been money? Rawlings earned significant income from Cross Creek, at least in part by making a laughingstock of the officious Cason, a fact that likely accentuated her erstwhile friend’s outrage.

But Cason doesn’t appear to have cared much for money. Hadley, her great-nephew, believes that Rawlings had simply “hurt Aunt Zelma’s feelings.”

Cason, he recalls, “was a very caring person, but didn’t have much tolerance for people who engaged in a lot of baloney. That’s not the term she would have used. She was very salty of tongue.”

Hadley says Rawlings was likely shocked that Cason filed suit “because she knew Aunt Zelma was a tough old bird, and figured it would just roll right off her back. But Aunt Zelma felt that this was a betrayal, and it just got to her.”

In any case, Cason’s 11-page, four-count declaration, which included a claim of libel, was filed on January 8, 1943, in the Alachua County Circuit Court. It named Rawlings and Baskin as co-defendants, since husbands were then jointly liable for the torts of their wives.

Cason was represented by Kate Walton, one of the first five women to be admitted to the Florida Bar, and her father, J.V. Walton, in whose Palatka practice she worked.

The lawsuit, for which Cason sought $100,000 in damages, was at first dismissed by Judge John A.H. Murphree, and then appealed to the Florida Supreme Court with an emphasis on the invasion of privacy claim.

In the appeal, Kate Walton argued that every citizen, apart from public figures, has a reasonable expectation of privacy and “the positive right to be left alone.”

The court agreed with Murphree’s dismissal of three counts, but ruled that Cason was entitled to be heard on her invasion of privacy claim. For the first time in Florida history, the court had recognized invasion of privacy as a redressable civil wrong.

A petition for a rehearing made by Rawlings’ tenacious lawyer, Philip May of Jacksonville, was denied, and Rawlings adamantly rejected May’s suggestion that she offer Cason a settlement.

Her reasons “were both personal and professional, closely tied to the emotions generated by the suit and Marjorie’s sense of duty as a writer,” according to Patricia Acton, who wrote 1988’s Invasion of Privacy: The Cross Creek Trial of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings.

May and Rawlings, preparing for an epic battle with “my friend Zelma,” then hired larger-than-life Gainesville lawyer Sigsbee Scruggs to assist the defense in Murphree’s typically quiet Gainesville courtroom.

No one could have predicted that a final resolution would take more than five years to achieve — and that the ultimate outcome would leave everyone dissatisfied.

Although the Florida Supreme Court had recognized that invasion of privacy was actionable, it had not yet ruled on a case that established a right to privacy for everyday people outside the limelight.

May and Scruggs sensed that the court, if given an opportunity, was predisposed to issue just such a ruling. Consequently, they sought to position Cason as a public figure whose activities were “of legitimate public interest.” If that were true, then any right to privacy, even if it existed, would not be applicable in her case.

In addition, they made the rather outrageous contention Cross Creek was so important — so universally praised — that it should be exempt from such nonsense as invasion of privacy claims.

Scribner’s, Cross Creek’s publisher, was ostensibly supportive, but didn’t offer to defray Rawlings’ legal fees — a fact that was disappointing to Rawlings, since editor Maxwell Perkins had specifically suggested that she elaborate on her relatively tame description of Cason.

Prior to the publication of Cross Creek, the author had written to Perkins regarding the possibility of just such a predicament: “These people are my friends and neighbors, and I would not be unkind for anything, and though they are simple folk, there is the possible libel danger to think of. What do you think of this aspect of the material?”

Perkins had replied that he saw little reason for concern “because of the character of the people … but you are the one who must be the judge.”

Rawlings, to make certain, had sought assurances from two people about whom she had written: Tom Glisson and “Mr. Martin,” the man with whom she had feuded after shooting and feasting upon his errant pig.

Neither man — even Mr. Martin, the only person whose acquiescence Rawlings had feared was uncertain — had objected to their stories and descriptions being published in Cross Creek.

Of course, Glisson and Mr. Martin couldn’t speak for the entire community — although Rawlings seemed to assume that their approval was tantamount to universal consent.

Less surprisingly, there was never any concern expressed by either Rawlings or Perkins that the African-Americans depicted in Cross Creek might object to having their stories shared and to being described in derogatory terms.

Henry, Adrenna and Geechee — human beings whom Rawlings knew, not fictional characters whom she invented — are described using racially charged language that’s shocking to a modern reader.

Rawlings, in her telling, treats blacks with kindness and charity. But a paternal brand of racism imbues even her ethereal descriptions of Martha, the “dusky fate, spinning away at the threads of our Creek existence.”

Although Rawlings had developed a friendship with African-American folklorist Zora Neale Hurston, her racial attitudes remain troubling even to scholars who contend that her views evolved — or at least were progressive for the time.

In her 1993 memoir, Idella: Marjorie Rawlings’ “Perfect Maid,” Idella Parker recalls that when Hurston visited Rawlings at Cross Creek she was asked to spend the night in the tenant house — despite having spent the day drinking and laughing with her host.

Perhaps, then, any number of African-Americans who lived in Cross Creek might have wished to take legal action against the famous white woman who had ridiculed and demeaned them in her widely read work.

Because of pervasive racism, however, no black person was likely to be taken seriously in an invasion of privacy claim. As a white woman, Cason could at least get a hearing.

Cason v. Baskin, which got underway on May 20, 1946, was every bit the circus one might expect.

The Miami Herald, in a preview, announced that “Cross Creek, with its original real-life cast — definitely not a motion picture — moves into [Gainesville] Monday for an indefinite run in the circuit court room here … Just about every other figure in the book except Dora, the Jersey cow, has been called as a witness.”

Following jury selection — none of the prospective jurors, to Rawlings’ amusement, had read Cross Creek, although it had already been a Book-of-the-Month Club selection — J.V. Walton delivered an opening argument for the plaintiff.

“Miss Zelma Cason is an ordinary citizen of Island Grove,” he said, “and went about the ordinary affairs of life and her pleasures and business, avoiding that which would point her out as above or apart from persons of her community.”

But that was before the notoriety of Cross Creek, in which “things that have been written about Miss Cason … are so intimate and of such a nature that as a matter of law it violates her right of privacy and entitles her to an affirmative verdict for nominal damages.”

He added that substantial damages should be awarded if it could be proven that Cason’s physical and mental health had been impacted by the ordeal. Even if Rawlings’ description of Cason was entirely true, he reminded jurors, it was not a defense against invasion of privacy.

Scruggs followed, insisting that Rawlings could not have felt malice toward a woman whom she considered to be a friend, and that Cason “knew, or should have known, that she would become a character, herself, in a book pertaining to the people of that community; the plaintiff, herself, being one of the outstanding parties in that community.”

Further, Scruggs insisted, “no sensible, or normal, or reasonable person could possibly have been offended by what was written about her in the book.” Cason, he concluded, had suffered no damages and was entitled to no compensation — nominal or substantial.

While Scruggs’ argument that Rawlings held no malice toward Cason seems plausible, considering their long but sometimes volatile friendship, it otherwise strains credulity.

How could Cason have “known, or should have known” that she would appear as a character in one of Rawlings’ books? What reasonable person would not have been offended at the description Rawlings offered?

Relevant or not, the truth of the description — and the contrast on the witness stand between the peevish Cason and the eloquent Rawlings —carried the day, albeit temporarily, for Rawlings.

Cason offered curt responses, indicating that she had been ridiculed both in public and at her job with the State Welfare Board. As a result, she claimed, she suffered from “an ulcerated stomach” that required a strict diet.

But upon cross-examination, Cason was evasive about her use of profanity, and several prosecution witnesses tried unconvincingly to portray her as meek and unobtrusive, eliciting chuckles from spectators who knew better.

The defense countered with witnesses who described Cason as officious, foul-mouthed and embroiled in local politics, buttressing the contention that she could be considered a public figure.

Shifting focus from Cason to Rawlings, the defense called Hanna, the Rollins history professor, who testified that Cross Creek was “of tremendous importance, in view of its honest and its true and its comprehensive description of an important section of Florida; it’s an accurate delineation of characters, a sympathetic and truthful description in every way; one of compelling importance.”

Hanna was undoubtedly sincere — but he was also returning a favor. Rawlings, at the time of the trial, was publicly praising the professor’s new book, A Prince in Their Midst, which documented the adventures of Achille Murat, the nephew of Napoleon I, who had sought his fortune in Florida after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo.

Reviewing A Prince in Their Midst for the New York Herald Tribune, Rawlings had called it “a fascinating book that should appeal to readers who might be intrigued by a factual story of a European prince pioneering in America, claiming milk and whiskey as cure-alls … traveling through the Florida jungle with slaves, cattle and a pet owl, weighing royalty against the American idea.”

Given their mutual interest in over-the-top Florida characters, it’s easy to see why Rawlings and Hanna had become such fast friends. Certainly, Hanna did his best to position Rawlings as an iconic, unassailable figure who enjoyed “an international reputation as an interpreter of life.”

Hanna’s scholarly if hyperbolic testimony — and that of Dr. Clifford P. Lyons, a professor of English literature at the University of Florida —tried to advance the dubious notion that Cross Creek’s literary value immunized it from litigation.

The Waltons, though, weren’t even conceding that Cross Creek was a good book. During cross-examination and through the testimony of several easily offended witnesses, they attempted to discredit it as vulgar due to its descriptions of animal mating and dog excrement.

Cason fumed as Dessie Smith and Tom Glisson testified that they were pleased with their portrayals in Cross Creek, and that the description of Cason was, in their view, accurate. Said Glisson: “I figured it was a pretty good description of her, maybe with a lot of truth, the same as what she wrote about me.”

Five other witnesses — three of whom had been depicted in the book and two of whom had heard Cason use profanity — were prepared to testify for the defense, but weren’t called. Their testimony, it was ruled, would have been superfluous.

May then called his star witness, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, to the stand. “[Rawlings] was more than just a local celebrity to those awaiting her trial testimony,” writes Acton. “She was, they knew, a world-famous author and a colleague of the literary greats. She was also an earthy, friendly and funny woman. It was obvious that Zelma was swimming against a sympathetic current running strongly in favor of her opponent.”

Under May’s questioning, Rawlings kept a straight face while deconstructing the offending description of Cason phrase by phrase, insisting that it was meant only as a tribute to a caring and competent woman for whom she had nothing but admiration.

J.V. Walton’s cross-examination couldn’t trip Rawlings up, although he managed to elicit the fact that her net worth had swelled to $124,000 — the equivalent of approximately $1.5 million in 2018.

May, sensing an opportunity, lobbed Rawlings a softball question. Did she write for money?

Her reply: “No. [I write] because it is in my blood and bones to write, you might say. I have done it so long. It is the thing I do, that’s all; just as another man wants to be a carpenter, or something of the sort; and to interpret the Florida country that I love so, and the Florida people, to the best of my ability; and if it is received well and if it sells … it is simply good fortune.”

Good fortune indeed. The prickly Cason never had a chance against the beloved author and local luminary. On May 28, 1946, after two hours of closing arguments and a 15-page charge to the jury, a ruling in favor of Rawlings was reached. The jury had deliberated just 28 minutes.

Wrote Hanna to Rawlings: “To refer to [the lawsuit] as a damn shame is to make a statement of supreme under emphasis. You will realize then, how elated we were over the outcome. I was, of course, more than glad to testify; I only wish I could have thought of the many things to inject into the testimony that occurred to me, too late.”

As it turned out, however, Hanna had already said far too much.

On September 14, the Waltons filed a second appeal to the Florida Supreme Court. The case was argued by May, representing Rawlings, and Kate Walton, representing Cason.

On May 23, 1947, almost a year following the Gainesville verdict, the court ruled that Cason had, in fact, proved her invasion of privacy claim, and was not a public figure whose privacy rights had been relinquished.

Furthermore, the court ruled, Murphree had confused the jury by allowing evidence of Rawlings’ eminence, which was irrelevant to Cason’s claim. Hanna’s fawning testimony — and that of others who had lauded Cross Creek as a masterpiece and its author as an international literary icon — was specifically cited as being prejudicial.

However, the court found that Cason had failed to prove harm from the notoriety or that Rawlings had acted with malice. The judgment for Rawlings was reversed, and a new trial ordered with the stipulation that Cason could recover only nominal damages if she won.

Kate Walton — who had sought a rehearing, which was denied — proposed to May that both parties stipulate to damages of $1 plus court costs and end the matter.

May encouraged Rawlings to declare a moral victory and move on. Rawlings, still seething, mulled an appeal to the United States Supreme Court as a matter of principle and on behalf of all writers.

Ultimately, however, both lawyers appeared before Murphree and mercifully concluded Cason v. Baskin. It was August 9, 1948 — more than five years after the case was first introduced.

Cross Creek would be Rawlings’ last book about Florida. Exhausted by the trial and beset by health problems, she would die on December 14, 1953, at age 57. Cason died on May 20, 1963, at age 73.

Both are buried in the Antioch Cemetery near Island Grove, within a few feet of one another.

Five years of expense and exacerbation could almost certainly have been avoided had Rawlings toned down the harsh description of Cason or had she created an equally memorable composite character, altering a few recognizable details and changing the character’s name.

No sacred literary principle would have been violated by taking these pragmatic pre-emptive steps. Cross Creek, after all, wasn’t reportage; it was described by Rawlings herself as “a limited, selective autobiography” that was based on fact but wasn’t always strictly factual.

Despite the right to privacy, it’s unusual for a writer to lose an invasion of privacy case when malice isn’t proven. Revelatory memoirs, for example, would be impossible to write if such suits were easily winnable.

Still, Cason v. Baskin still gives writers reason to pause before they unleash literary vendettas against obscure antagonists or characterize real people in works that aren’t meant to be definitive or reportorial.

Amy Cook, an attorney who blogs for Writer’s Digest, says: “Writers don’t get sued very often — and thanks to the First Amendment, even when they do, they usually prevail. But you don’t want to put yourself into a position to endure any sort of lawsuit, even if the odds are you’d end up victorious.”

Kiri Blakeley, a contributor to Forbes magazine, advises writers who are depicting real people to tell their subjects in advance and perhaps allow them to read the copy prior to publication, as Rawlings did in at least two instances: “If you take out the ‘gotcha!’ factor when you write about them, you usually diffuse their ire.”

Critic David L. Ulin asks a question that Rawlings would have done well to consider: “What do we owe our subjects? Do we have the right to tell their stories at all? Such complications become more vivid when we consider them through the lens of privilege: the privilege of the storyteller to control or shape the narrative.”

In writing Cross Creek, Rawlings had fundamentally altered her relationship with “the simple people” surrounding her.

Now they realized that they weren’t merely friends and neighbors, but potential literary characters. Their private lives were open to exploitation — a word not used lightly — by a noted author for private gain.

In the wake of the trial, some may have become more guarded and less authentic in Rawlings’ presence. Others, hoping to earn a measure of fame, may have behaved in a more outlandish manner than usual in a bid to catch her attention.

Marion Winik, who has written six memoirs, notes: “The act of writing about another person occurs not just in the world of literature but in real life. It cannot help but change your relationship, and this should be the first thing you think about.”

The purity of Cross Creek could never be recaptured, and Rawlings had only herself — and her cavalier attitude regarding the feelings of her once-guileless subjects — to blame.

The relationship between Rawlings and Cason in the aftermath of the legal battle was for years the subject of speculation among Rawlings scholars.

But Hadley, who today owns a 72-acre blueberry farm in Cross Creek dubbed “Aunt Zelma’s,” says the pair reconciled — and he can prove it. In 2009, he discovered two previously unknown letters from Rawlings to Cason confirming that the strong-willed women had renewed their bond.

“They made amends,” Hadley says. “Of course, it was never the same as before.” One of the conciliatory letters had been stashed in a strongbox at Cason’s Island Grove home, which Hadley eventually inherited. The other was among the personal papers of Hadley’s father, insurance executive Ralph “Bump” Hadley, who died in 2004.

The letters “demonstrate an intimacy and a shared history between the two,” says Leslie Kemp Poole, an assistant professor of environmental studies at Rollins and executive director of the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Society. The tone is chatty, funny, newsy, gossipy and at times poignant — as letters between longtime friends generally are.

Poole and Carol Courtney Hadley, wife of Terry Hadley, published the correspondence as part of a 2012 article for the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Journal of Florida Literature. Its unambiguous title: “Marjorie and Zelma: Friendship Restored.”

In the first letter, written from Cross Creek, Rawlings alludes to visiting Cason when seeking comfort regarding the terminal illness of her beloved former brother-in-law, Jim Rawlings.

In the second letter, written from her home in New York, Rawlings describes a dream in which she was ill and “[you] came to me with flowers, and you drove away such strange enemies … I felt you must be thinking about me, too.”

It was a sweet, hopeful sentiment — and one that was undoubtedly true.

PRESERVING CRACKER CULTURE

The Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Society celebrates and promotes the life and works of this Pulitzer Prize-winning author who opened the eyes of Americans to the beauty of rural Florida and the hardscrabble lives of the people who lived there.

Leslie Kemp Poole, an assistant professor of environmental studies at Rollins College, is the executive director of the organization — continuing the college’s historic ties with the author of Cross Creek and The Yearling.

Rawlings and her husband, Charles, both journalists, moved to a ramshackle wooden farmhouse in the north Florida hamlet of Cross Creek in 1928. They hoped to dedicate their lives to writing with an income supplemented by fruit from their 72-acre orange grove.

Rawlings felt an immediate spiritual connection: “When I came to the Creek, and knew the old grove and farmhouse at once as home, there was some terror such as one feels in the first recognition of a human love, for the joining of person to places, as of person to person, is a commitment to shared sorrow, even as to shared joy.”

That feeling was not shared by Charles, who left the area after a few years. The marriage ended in divorce.

Rawlings, however, had found her calling in the natural and human community, located on the edge of what was then called the Big Scrub — now the Ocala National Forest.

“We at the Creek need and have found only very simple things,” she later wrote in Cross Creek. “We need above all, I think, a certain remoteness from urban confusion, and while this can be found in other places, Cross Creek offers it with such beauty and grace that once entangled with it, no other place seems possible to us, just as when truly in love none other offers the comfort of the beloved.”

Spending time with local residents while listening and recording their tales inspired Rawlings’ work, which was soon being published in magazines and books.

Her tale of a young boy and his pet fawn, The Yearling, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1939, and many of her books set in the area received critical and public acclaim. Her home is now a historic state park and has been designated a national landmark.

For many, Rawlings’ works evoke a Florida and a way of life that is rapidly disappearing.

“She reminds us of what Florida once was and how the land shaped the people who fought to make a living in the early twentieth century,” says Poole. “Her books are in many ways timeless. I’ve read them at different stages of my life, and they always speak to me about the human spirit and the immense beauty of our state.”

Philip S. May Jr., whose father served as Rawlings’ attorney, founded the society to honor, preserve and encourage an ongoing interest in the author’s works.

The first official meeting of the group was in 1987, followed the next year with the organization’s first annual meeting. This year, the 160-member group met in Mount Dora for a two-day conference that featured an array of academic speakers as well as writers — professionals and students — who have been inspired by Rawlings’ work.

Next March, the group will meet in Tarpon Springs. The public is welcome to attend. Visit rawlingssociety.org for more information about the Marjorie Rawlings Society and its activities.

RAWLINGS AT ROLLINS

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was a frequent visitor to Winter Park — a town about as unlike Cross Creek as any imaginable — and Rollins College.

She enjoyed friendships with President Hamilton Holt — with whom she frequently corresponded — and Professor of History Alfred J. Hanna, who testified on her behalf during the infamous Cross Creek invasion of privacy suit by Zelma Cason.

Rawlings had received an honorary doctor of literature degree from the college in 1939, and had spoken at its whimsically named Animated Magazine in 1934, 1937, 1938, 1941 and 1945.

Rawlings and Holt corresponded over a 16-year span that ended only during Holt’s final illness.

“You are a very remarkable woman; I wish to know better what goes on in your head,” Holt wrote Rawlings in 1938. Rawlings, referencing her books, replied: “Why, bless us, South Moon Under and Golden Apples and The Yearling are inside my head!”

John “Jack” Rich, a Rollins student who later became the college’s dean of admissions, served as an escort for Rawlings during her 1938 campus visit.

In a 2005 oral history interview conducted by Wenxian Zhang, head of archives and special collections at the Olin Library, Rich recalled Rawlings as “a delightful woman, and so interesting,”

He also remembered the delight Rawlings took in using bawdy language. “If she had as many as two cocktails, she started to swear like a trooper,” Rich said. “Just for the fun of it! ‘You bastard, you! So nice to see you!’ Something like that. Of course, the students loved her.”