Few colleges and college towns are as intertwined, geographically and historically, as Rollins College and Winter Park. But when the college recently announced its biggest off-campus building initiative in years — a cluster of three projects dubbed the Innovation Triangle — some locals instinctively balked.

“Rollins consumes City of Winter Park services and does not pay property taxes,” wrote one poster on a Facebook page devoted to discussions of city-related political issues.

This easily debunked view persists in some circles, and usually comes up whenever the college buys property located outside the boundaries of its 70-acre campus hugging Lake Virginia.

Since Rollins has been a player in the local commercial real estate market since the late ’90s, its economic impact on the city has been a relatively frequent topic of discussion.

On one point, there’s apparent unanimity. The presence of a prestigious liberal arts institution is confirmation of Winter Park’s stature as the cultural and intellectual mecca of Central Florida. It’s hard to put a price tag on that.

Still, the questions persist. Is the college a beguiling but costly jewel in Winter Park’s crown, valuable primarily for its prestige? Or is it a powerful economic engine whose presence is crucial to the community’s prosperity?

It’s fair to say that the relationship is symbiotic. But it’s not fair — or accurate — to say that Rollins doesn’t pay property taxes. What’s more, property taxes comprise only a fraction of the college’s contribution to the city’s ongoing prosperity.

“We haven’t commissioned a formal economic impact study in a number of years,” says Allan E. Keen, chairman and CEO of The Keewin Real Property Company and chair of the college’s board of trustees. “There just hasn’t been a need. In our view, the facts are pretty obvious.”

The last such report was in 2008. A 27-page tome by Pittsburgh-based Tripp Umbach estimated that in 2006, the college generated $56.9 million in economic activity for the City of Winter Park, $110.6 million for Orange County and $204.9 million for the State of Florida.

Tripp Umbach, like all such consultants, used complex calculations to determine the college’s direct and indirect economic impact. In addition to taxes paid and estimated local spending, it analyzed such factors as volunteer hours from students and faculty to quantify the college’s social and quality-of-life benefits.

Similar analyses are frequently used by local governments to justify use of taxpayer dollars for construction of high-profile projects such as sports facilities or convention centers. The resulting documents are generally obtuse to non-economists — and subject to suspicion because vested interests usually commission them.

However, a few easy-to-understand numbers related to Rollins offer an unambiguous and irrefutable overview of the college’s importance to the city’s economy.

DOLLARS AND CENTS

All Rollins-owned property in Winter Park is valued at a whopping $196,726,893, according to the college’s Office of Business and Finance and the Orange County Property Appraiser’s Office.

Property used for educational purposes — including the 70-acre main campus — is tax exempt. So last year, no taxes were paid on property valued at $117,322,856.

However, property not used for educational purposes, valued at $79,404,037, remained on the tax rolls. In 2017, the college ponied up $998,445 — an increase of $148,222 from 2015 — making it the city’s second-largest payer of property taxes.

At the current millage rate of $4.09 per $1,000 of taxable value, almost a third of that amount — $324,945 — bolstered the city’s general fund. The remainder went to Orange County and Orange County Public Schools. (The millage rate has remained unchanged for a decade, but valuations have soared.)

Within the city, only sprawling Winter Park Village, a major mixed-use development on U.S. Highway 17-92, had a higher property tax bill than Rollins. That’s because the college rarely changes the taxable status of its real estate purchases. And its commercial properties are taxed no differently than those owned by for-profit investors.

“So, people think Rollins doesn’t pay property taxes,” sighs Jeffrey Eisenbarth, the college’s recently retired vice president for business and finance. “That’s an urban legend. And it doesn’t seem to go away, no matter how many times we show and tell.”

In fact, the college’s property tax bill has soared since the Alfond Inn’s 2013 opening. The boutique hotel, which sits on a 3.3-acre parcel at the corner of New England and Interlachen avenues, is valued at $26,164,543. It received a property tax bill of $359,626 in 2017 — an increase of $98,510 from two years ago.

Of more than 60 properties bought by the college since 1993, 45 of them — or 75 percent — have remained on the tax rolls, adds Eisenbarth, who ended a productive 10-year stint at the college in May. He was replaced by Ed Kania, who held a comparable post at Davidson College in Davidson, North Carolina.

Likewise, Rollins-owned properties get no breaks when it comes to utilities, which have been owned by the city since a 2005 break from Florida Power & Light.

In the 12 months prior to September 2018, the college spent $2,257,517 on electricity, making it the city’s largest user. The college’s water bill — $153,310 — was behind only AdventHealth, formerly Winter Park Memorial Hospital.

Rollins employees and students clearly bolster local businesses, says Betsy Gardner Eckbert, president and CEO of the Winter Park Chamber of Commerce. “When students leave for the summer, we feel the impact downtown,” she says.

The college has 726 full-time-equivalent staffers and faculty members who earn a cumulative $71,801,893 per year. There are 3,093 students, including those enrolled in the College of Liberal Arts — the day school — and its two evening programs, the Hamilton Holt School and the Roy E. Crummer Graduate School of Business.

That’s a lot of money and a lot of people within walking distance of Winter Park’s busy Central Business District. And the college itself spends heavily on an array of products and services from local suppliers.

What would a formal economic impact study show now? Nine years ago, when Tripp Howard calculated $56.9 million, the college’s property taxes were just $140,000 and its payroll was just $46.4 million.

Since then, its property taxes have increased seven-fold — due in large part to development of the Alfond — and its payroll has leapt by 54 percent. Depending upon the methodology used, a consultant could likely justify a figure north of $100 million today.

And Gardner Eckbert notes that the college’s international students often have parents who are prime relocation prospects. The chamber has even initiated a “global membership” to keep moms and dads around the world connected to — and interested in — Winter Park

BUILDING ON SUCCESS

Rollins entered the commercial real estate arena in 1999, when it developed SunTrust Plaza and an accompanying parking garage on the 400 block of Park Avenue South. Not everyone was happy about it.

The college already owned the 2.5-acre site, upon which sat a three-story brick building that once housed the Winter Park Grade School, later Park Avenue Elementary. Rollins, which had bought the property in 1961, used the building for classrooms and offices. But by the late 1980s, it had fallen into disrepair and had become structurally unsafe.

The college announced plans to demolish the building — which had been built in 1916 — and redevelop the site. The move inflamed preservationists, some business owners and many longtime residents who had attended the school and retained a sentimental attachment to it.

Still, after much debate, SunTrust Plaza was opened as a three-story, 82,000-square-foot complex abutting an 850-space parking garage. Today’s tenants include Gap, Starbucks, Restoration Hardware and Merrill Lynch, as well as its namesake bank.

At 40 feet tall, the structure exceeds the city’s height limit by 10 feet. But with the third story partially recessed, it doesn’t feel out of scale with the rest of Park Avenue. And last year it generated $273,615 in property tax revenue.

Subsequently, Rollins began buying various commercial properties along the south side of West Fairbanks Avenue, from the campus entrance to the railroad tracks.

In 2012, it redeveloped Winter Park Plaza — a strip center anchored by Ethos, a vegetarian restaurant — and is now landlord to an array of businesses, from a waxing salon to a vitamin emporium.

The center’s original developers had defaulted on a $7 million note, and the college snapped it up for $2.8 million via an online auction. It generated $49,279 in property taxes last year.

Other college-owned commercial properties lining Fairbanks bring in considerably less, but all contribute proportionally, based upon their assessments. A few properties, however, have been removed from the tax rolls as they’ve been converted to educational use.

In 2015, for example, Rollins jumped across Fairbanks to buy its only property on the north side of the street — the building at 315 West Fairbanks that for years housed the law offices of the late Russell Troutman.

That building — which now houses the Hamilton Holt School — no longer generates tax revenue. Neither does 200 West Fairbanks, once home to a bar and restaurant and now site of the college bookstore.

In 2007, Rollins began buying up townhomes, corralling nine units on Orchard Avenue near Mead Botanical Garden. The college uses these and other scattered townhomes and single-family homes for faculty housing. New hires pay market rate for rent and may remain for a maximum of three years.

The homes remain on the tax rolls because they’re considered incidental to the college’s core educational mission. Faculty housing generated $81,981 in property taxes last year.

In the Central Business District, Rollins owns the Samuel B. Lawrence Center, a city block gifted to the college in 1994. A four-story commercial building on the site, home to Valley National Bank and other tenants, generated $89,530 in property taxes last year.

Although the Lawrence Center is slated for redevelopment through the Innovation Triangle initiative, the commercial building will stay and remain on the tax rolls.

A WIN WITH THE INN

Still, the biggest commercial project ever undertaken by the college was the Alfond. “I was on the job two months and got the job of hotel developer,” recalls Eisenbarth, who had been hired from a comparable post at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon.

The Alfond family — longtime college benefactors — had already committed to contributing $12.5 million for the project, with the condition that profits be used to provide scholarships and endow a scholarship fund. But $12.5 million wasn’t nearly enough to get the job done.

Instead of partnering with a developer, though, Eisenbarth and Keen recommended that the college finance the remainder with a $20 million loan from its reserves, to be repaid over 25 years at 4.5 percent interest.

In 2009, the college spent $9.9 million for a 3.3-acre parcel at the corner of New England and Interlachen avenues, just blocks from the campus.

On the site once stood the legendary Langford Hotel, a local landmark that closed in 2000 and was demolished in 2003. Ground was broken for the new hotel in November 2011, and its grand opening was in August 2013.

Almost immediately, the 112-room facility began earning rave reviews. Most recently, in Conde Nast Traveler’s annual Readers’ Choice Awards, it was rated No. 1 in Florida, No. 7 in the U.S. and No. 63 in the world. It also holds a AAA Four-Diamond rating.

But if you’re an accountant, you’ll be more impressed by the numbers. Last year, the Alfond grossed more than $16 million and earned an operating profit of more than $6 million.

From the net, the college was repaid $1.2 million. The remainder bolstered Alfond Scholars, a program established by the hotel’s namesake family. This agreement will continue for 25 years and is expected to eventually boost the scholarship endowment to $125 million.

FOR THE FUTURE

Keen says the college isn’t looking to buy more property unless it’s strategically placed near the campus or offers proximity to other college-owned assets. “We try to be a good neighbor,” he notes. “That’s why nobody builds anything prettier or better than we do.”

Not that they don’t try. Comparably sized colleges, particularly those in unremarkable towns or even rural areas, are increasingly promoting mixed-use commercial and residential development around their campuses to help lure students and faculty.

But such colleges rarely have the expertise — or the cash — to do it themselves. So they take on development partners who assume the risks (and reap most of the rewards).

However, creating an appealing college-town atmosphere around Rollins has never been necessary. It’s hard to improve on Winter Park just the way it is — and has been for generations.

So why is Rollins in the development business? Because it can be, for one reason, blessed as it is with resources, expertise and an enviable location.

But it’s also positioning itself for growth — perhaps decades from now — and in the meantime generating healthy returns in both asset value and profit. Not including the Alfond, the college’s commercial real estate ventures in 2017 grossed $4.7 million and netted $2.6 million — an eye-popping 55 percent margin.

“The campus is landlocked and lake-locked,” says Keen. “When we buy property, it isn’t to sell. Rollins has been here for 130 years, so we hope to keep what we buy basically forever. Obviously, that means we look further ahead than most buyers would.”

Eventually, Keen says, much of the real estate Rollins absorbs may be used for campus expansion. But “eventually,” in this context, may mean generations from now. In the meantime, profits are supplementing the college’s budget and allowing for more generous financial assistance programs than would otherwise be possible.

“The sole purpose of our commercial real estate holdings is to provide revenue to support financial aid for our students,” says President Grant Cornwell. “We’re committed to keeping Rollins financially accessible to qualified students without regard to their socioeconomic status. The only way we can do this is by having sources of revenue other than tuition to support our budget.”

That’s especially important, considering that Rollins is the most expensive college in the state, according to a survey in Business Insider. Tuition, room, board and other expenses amount to $67,110 per year — more than triple what a state university costs.

But very few actually spend that much. According to the college, the average financial aid package for students who show a demonstrated need is $35,000 — and more than 85 percent of students receive assistance in some form.

“It’s certainly not a trend for small liberal arts colleges to do what we’ve done, because no other small liberal arts college is located in Winter Park,” says Cornwell. “Unlike other colleges, we’re incredibly fortunate in that we happen to be situated in such a beautiful, charming and prosperous city.”

ROLLINS EARNS NATIONAL KUDOS

For the 24th consecutive year, U.S. News & World Report has ranked Rollins College among the top two regional universities in the South in its annual rankings of “Best Colleges.”

Rollins was ranked No. 2 among the 165 colleges and universities in that category, which encompasses schools that provide a full range of undergraduate and master’s-level programs. Elon University in Elon, North Carolina, finished first.

“Rollins is proud to be recognized so prominently among the nation’s best colleges year after year,” says Rollins President Grant Cornwell. “Our longevity at the top of this ranking is a testament to the college’s long tradition of academic excellence, the rigor of a Rollins education and the achievement of our innovative faculty and industrious students.”

The U.S. News & World Report rankings evaluate colleges and universities on 16 measures of academic quality, including such widely accepted indicators of excellence as student retention, graduation rates and qualifications of faculty members.

In addition to ranking among the top regional universities in the South, Rollins was recognized for its strong commitment to undergraduate teaching, its high proportion of international undergraduates and for having one of the best undergraduate business programs in the country.

The college was also named one of the South’s most innovative schools. And it made the list of schools whose 2017 graduates had the lightest debt loads. The average was $32,700 for those who completed undergraduate degree programs.

INNOVATION TRIANGLE IS MOVING FORWARD

Rollins recently announced — and then unexpectedly placed on temporary hold — plans for what it dubbed the Innovation Triangle, which involves redeveloping the Samuel B. Lawrence Center and expanding the Alfond Inn.

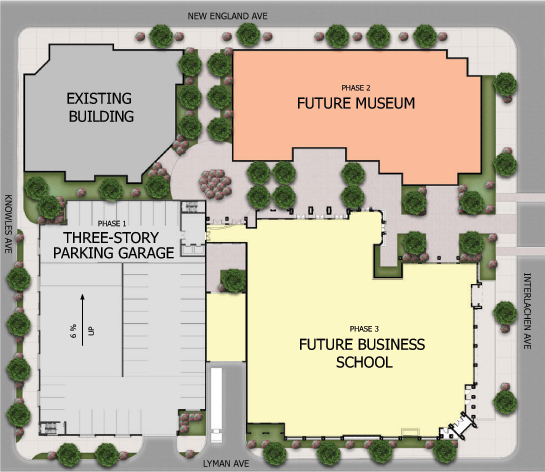

Occupying a city block in downtown Winter Park, the Lawrence Center — owned by the college since 1994 — is bounded on the north by New England Avenue, the south by Lyman Avenue, the west by Knowles Avenue and the east by Interlachen Avenue, across the street from the Alfond.

According to preliminary plans, the four-story, 40,000-square-foot building now occupied by Valley National Bank and other tenants would remain on the site’s northwest corner. Two new buildings — one housing the Roy E. Crummer Graduate School of Business and one housing the Cornell Fine Arts Museum — would be built on the southeast and northeast corners, respectively.

The Pioneer Building, on the southwest corner, would be razed and replaced by a two-story, three-level parking garage. The city had expressed interest in negotiating a public/private partnership that could have added one or two levels and at least 120 additional spaces of public parking.

However, in late August the college announced that it was delaying the Innovation Triangle projects “in order to explore and evaluate some cost-saving and project-sharing opportunities that will benefit the college and the community,” according to a statement.

Plans for the Alfond expansion were set to go before the Winter Park Planning & Zoning Commission in September. The Lawrence Center redevelopment was scheduled for consideration in October, when the college planned to seek a conditional use permit for the property’s site plan.

Later, once details for the buildings had been finalized, a zoning change from O-1 (office) to PQP (public, quasi-public) would have been required before the Lawrence Center could get underway.

Had the college changed course? Had the spectre of public opposition to city participation in a parking garage prompted a retrenchment?

“The hotel expansion, the business school and the museum are all absolutely going forward,” says Allan E. Keen, chairman and CEO of The Keewin Real Property Company and chair of the college’s board of trustees. “And they’re going forward apace. I regret it if anyone took our statement to mean there’d be a prolonged delay, or that we’d abandoned any of these strategic initiatives. We’re just working some details out.”

More specifically, college officials wanted to think through the parking options. While a garage at the Lawrence Center in which the city partnered might have been welcomed by visitors to the Central Business District, it wouldn’t alleviate the long-standing parking shortage on the main campus.

Soon to exacerbate the problem is a new $40 million student residential complex, which is being built to replace the mundane maintenance and storage buildings now occupying prime Lake Virginia real estate.

The housing is needed because the college is raising its two-year residency requirement to three years, moving juniors onto campus. When it all shakes out, college official estimate that about 200 more students will list 1000 Holt Avenue as their address.

Of course, most juniors already drive to class from wherever they live. But having them as full-time residents will mean more cars, more of the time, vying for space.

One of several possibilities being discussed is construction of a parking garage on a college-owned surface lot bordered by Fairbanks Avenue and Ollie Avenue, abutting Dinky Dock Park. If that happens, the spaces would be only for college use.

None of this has any relevance to the Alfond expansion, which has included in its design about 150 additional parking spaces in an underground garage. The hotel project was conceptually included as part of the Innovation Triangle but is unaffected by what happens — or doesn’t happen — in the Lawrence Center, according to Keen.

Plans call for the addition of 70 rooms to the 112-room hotel along with a 7,000-square-foot spa and health club, a 4,000-square-foot meeting space/gallery and 323 square feet of retail space.

“We want to do this expansion in the most efficient and effective way possible,” says Keen. “But all of the projects we’ve announced are moving ahead.”

Rollins President Grant Cornwell says that the Innovation Triangle initiative will strengthen three of the college’s major strategic assets by further integrating them into the community.

Cornwell notes that the Alfond clearly needs additional capacity for lodging and events. “What I hear from fellow Winter Park residents all the time is they can’t imagine Winter Park without the Alfond,” he says. “I also hear that they can never get a room. We know now is the right time to move forward with the proposed expansion.”

Having the museum and the business school join the hotel in a downtown location, he adds, will “impact business synergies and provide an enhanced arts and culture presence” in the Central Business District.

“Rollins greatly values our history and involvement with Winter Park,” Cornwell continues. “We’re proud that our being here and the programs we offer are high on the list of what makes Winter Park a great place to live and work.”

The Alfond and the Cornell are already soulmates, notes museum director Ena Heller. Ted and Barbara Alfond, both members of the Class of ’68, gave the college $12.5 million to jump-start construction of the hotel. They also donated a world-class contemporary art collection, pieces of which are displayed at the hotel on a rotating basis.

More space will allow more of the museum’s encyclopedic collection to be on view, Heller says. The current Cornell building, tucked away on the Rollins campus, is just 10,000 square feet. The proposed building is about 36,000 square feet.

“It’s very exciting,” notes Heller, who adds that the move will make the museum more inviting for the public and more conducive for teaching — which is crucial for a curricular museum with a college affiliation.

“There’ll be more galleries, room for lectures and a seamless connection between the museum and the Alfond,” she says. “The facility we have now is inadequate for events and classes.”

Best of all, upon completion of the new Cornell, both the northern and the southern reaches of the Central Business District will be anchored by world-class museums. The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, located on Park Avenue North, has been a major downtown draw since 1997.

The Crummer, which operates on the main campus from Roy E. Crummer Hall and the Bush Executive Center, will also be a benefit to the Central Business District, says Cornwell. Its new building is expected to be 80,000 square feet.

“The thought was to encourage linkages between the Crummer’s resources and those who run businesses in Winter Park,” he notes. “We see a natural synergy here that we can improve upon.”

The Innovation Triangle’s timetable is flexible, says Keen, but will happen as quickly as possible. Funding from an anonymous donor is already in place for the Alfond expansion, which is expected to cost between $35 and $45 million.

The Cornell and Crummer projects, however, will depend entirely upon fundraising. The business school could cost between $50 and $60 million and the museum between $30 and $40 million, all of which must be raised through philanthropy.

At first glance, Cornwell notes, a hotel, a museum and a business school appear to have little in common. But, he adds, placing the trio of projects under the Innovation Triangle umbrella makes sense for a place as eclectic as Rollins.

“As an educational institution, we constantly strive to stimulate new learning paradigms and encourage the application of new ideas to complex problems,” Cornwell says. “Specifically, the Innovation Triangle highlights the intersections of art, business and interdisciplinary teaching and learning.”