When Winter Park-based sculptor Barbara Sorensen rummages through the aisles at Miller’s Hardware, she isn’t looking for obscure widgets to repair household appliances, or chemical concoctions to remove mold from her bathroom grout.

She’s looking for artistic inspiration.

“I think at first the staff thought I was a little nuts,” says the ebullient Sorensen, a lively and stylish woman who laughs easily and seems decades younger than her 72 years. “But I found some wonderful material that really works for me.”

At Miller’s Hardware?

The densely packed store is, in fact, where Sorensen discovered tubular aluminum foil ductwork manufactured for use in clothes dryer exhaust systems.

Excited by the creative possibilities, she ordered boxloads of the stuff. And why not? It’s lightweight, easy to bend and shape, and can be torn almost as easily as paper.

“Miller’s Hardware is great,” says Sorensen, who is surely one of only a handful of locals who consider the legendary handyman haven to be an art-supply store in disguise. “Any time I can give them a plug, I do.”

The pedestrian but pliable ductwork — torn into crumpled squares, mounted on wood and painted white — has been repurposed as an immense but whimsical installation at the Orlando International Airport.

Ripples in White, which is part of OIA’s expansive permanent art collection, can be seen at the new South Airport Automatic People Mover Complex.

No one who has followed Sorensen’s career should be surprised that she has figured out a way to create timeless art using a hardware-store item that, for most of us, serves no purpose apart from removing lint.

Since her earliest work — mystically infused “Pandora’s boxes” inspired by the Greek myth — Sorensen has consistently been inspired by the sheer joy of moving, molding and manipulating materials.

“My work is about the landscape and the environment,” she says. “My process is about how the earth was formed. I look at the landscape, interpret it and reinterpret it, processing it within. Then I give it back, transformed.”

Along the way, whether creating richly textured clay chalices, imposing bronze goddesses, weighty clusters of shields or colorful wire structures that she calls “dwellings,” her work seems both primal and contemporary.

And, unlike most art, Sorensen’s creations cry out to be touched. In fact, visitors are invited to feel the ridges, patterns and pebbles that make the art both a visual and a tactile experience.

Sorensen — with husband Gary and two young daughters — moved to Winter Park 35 years ago because, she says, “we just didn’t like the weather in Wisconsin.”

But she didn’t become a working artist right away.

Sorensen had earned an art education degree from the University of Wisconsin, Madison — where she studied under renowned ceramic artist Don Reitz — and had been a high school art teacher prior to relocating.

Once in Florida, however, she became “a car-pool mom,” putting her career on hold while raising children. But by the time the youngsters left for college, she had accrued a decade’s worth of pent-up creativity — and was ready to unleash it.

She soon found herself in the pottery studio of Stetson University art professor Dan Gunderson — another Reitz disciple — whom she cites as a major influence on her work.

“When Barbara switched gears, she put the same passion for parenting into her artwork,” wrote Gunderson in 2010, when he curated an exhibition dedicated to her work. “One look at her resumé will prove that she did all the right things. She had the drive to make it happen.”

In 1994 and 1997, respectively, her sculptures were spotlighted at the Albertson-Peterson Gallery in Winter Park and Orlando City Hall. In 1999, the Cornell Fine Art Museum at Rollins College staged Barbara Sorensen: Sculpture as Environment.

“That all got my adrenaline going,” says Sorensen, who seems to have an unlimited supply of the hormone coursing through her veins. Throughout the next decade, museums and private collectors around the country began clamoring for her work.

That’s partly because Sorensen was no ordinary potter. She had found new ways of expressing her artistic vision through primal, heavily textured and highly symbolic forms.

During family ski trips, she studied at Snowmass Village, near Aspen, at the Anderson Ranch Arts Center. There she connected with another soon-to-be mentor, ceramic artist Paul Soldner, who encouraged her to work on a larger scale and “helped me to find my own voice as an artist.”

Soldner, she adds, “told me to give myself permission to experiment and to grow.”

Workshops at Anderson Ranch, Sorensen recalls, consisted of “critiquing, going out for meals and firing kilns on those beautiful days and nights that only Aspen has. I remember a lot of sharing of ideas, of new and important turning points in my work, epiphanies and new directions.”

While out west, Sorensen also soaked up the stunning natural environment during long hikes, and “used the kiln to repeat nature’s formation.” Eventually, the family bought a condominium in Snowmass Village, where the family still spends part of the year.

Sorensen’s works, according to New York-based art critic Eleanor Heartney, “are rich with meaning — simultaneously referring to the landscape, acting as metaphors for time and embodying ideas pregnant with ceremonial and elemental implications.”

Goddesses — their elongated bodies twisting and stretching skyward — are breathtaking allusions to such forces of nature as whirling winds, erosion and ultimate decay. But they’re unquestionably beautiful; alluring in their slim, precarious balance.

Pandora’s boxes often feature lids embedded with actual gems and golden surfaces. Chalices, sometimes delicately poised on tiny bases, are adorned with colorful flounces that hint at the gowns of Minoan maidens.

Encrusted half-moons of clay become formidable shields, their surfaces gloriously ornamented with runes, pebbles, circles, incisions, crests and boldly colored bands. Most even bear the artist’s fingerprints.

Works from Sorensen’s boat-inspired series rest on floors or are suspended as if by magic from ceilings, casting ghostly multiple shadows and representing, perhaps, a journey between life and death.

Sorensen — whose work can be found in countless private and corporate collections — was never particularly fond of making flawless pottery on a wheel; she prefers to pull, twist, stretch and squeeze the clay, and to experiment with glazes, textures and unexpected enhancements.

Clay, in fact, isn’t the only medium she has mastered.

Wire “dwellings” are airy, colorful installations that look like X-rays of three-dimensional clay forms, while another series, inspired by wind, features strands of rope swirled to resemble tiny funnel clouds.

Other series reflect natural phenomena, such as the subtle shifting of sand dunes and the impact of wind and water on the striated stone outcroppings in Utah’s Zion National Park.

Works reflecting these assorted themes can be seen throughout Sorensen’s Windsong home — hanging on the wall, occupying nooks and crannies, and standing guard over gardens and a backyard swimming pool.

She works mostly in her garage, although she has warehouse space for materials in the Orange Blossom Trail area.

“My work isn’t the normal stuff that people turn out in clay,” she says. “And I’m always discovering new things. For example, clay had become sort of limiting. That’s when I went to Miller’s Hardware and found the dryer ducting.”

Although Sorensen’s work is prized everywhere, it’s particularly revered locally.

In 2010, the Museum of Florida Art in Deland staged Barbara Sorensen: Topographies, which was curated by Gunderson — her onetime professor. It was, at that time, the most complete overview of her work ever assembled.

An expanded version of Topographies came to the Orlando Museum of Art in 2012. The dramatic entrance to the exhibit was a cluster of stoneware speleothems — stalactite and stalagmite formations — that rose from the ground and descended from the ceiling.

More recently, the Mennello Museum of American Art unveiled a permanent display of Sorensen’s sculptures — including an enchanting “Chalice Forest” — on the facility’s grounds.

Inside the museum hung Ripples in White, which was spotted by a fellow Winter Parker: Carolyn Fennell, senior director of public affairs and community relations at OIA. Fennell thought the piece would be ideal for OIA and suggested that it be acquired by the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority.

“I’ve followed Barbara’s work for years,” says Fennell, who thought Ripples in White would be ideal for OIA’s collection since it evokes the calming vibe of the region’s many lakes. “There’s so much anxiety associated with travel, and we know that an art piece can really offer relief.”

Sorensen says she thrilled to have her work in OIA’s collection: “After all, Orlando is my town, so I couldn’t be more proud. It’s so exciting.”

What’s next for Sorensen? She isn’t slowing down, although she says she doesn’t do much heavy lifting any more — she has an assistant for that — and primarily concentrates on commissioned work.

She isn’t finished with metallic ductwork, she adds, although you never know what new medium she may encounter during her next visit to Miller’s Hardware.

Notes Sorensen: “If people acquire my art, that enables me to make more. And even though I’ve fulfilled a lot of my goals, I’m still discovering new things and think I still have something to say.”

AN ARTFUL WELCOME

One of the most extraordinary collections of Florida-themed art isn’t in a museum. It’s in the Orlando International Airport. And more than 44 million people every year see at least some of it.

“Art is a growing focus of airports,” says Carolyn Fennell, a longtime Winter Park resident and senior director of public affairs and community relations for the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority. “They’re moving from being simply receptacles to being welcoming gateways. More and more, you’ll see airports creating a sense of place through art.”

Fennell says that’s more important than ever because of the increased anxiety associated with air travel. “Art can offer relief,” Fennell says, while also highlighting what’s special about the region.

At OIA, most of the art — floor mosaics, sculptural installations, and an array of large-scale paintings and photographs — focuses on the natural environment.

Not all the works are literal representations. Winter Park-based sculptor Barbara Sorensen’s recently installed Ripples in White, which can be seen at the new South Airport Automatic People Mover Complex, is fashioned from crumpled clothes dryer duct material. But it calls to mind ripples of water seen in the region’s thousands of lakes.

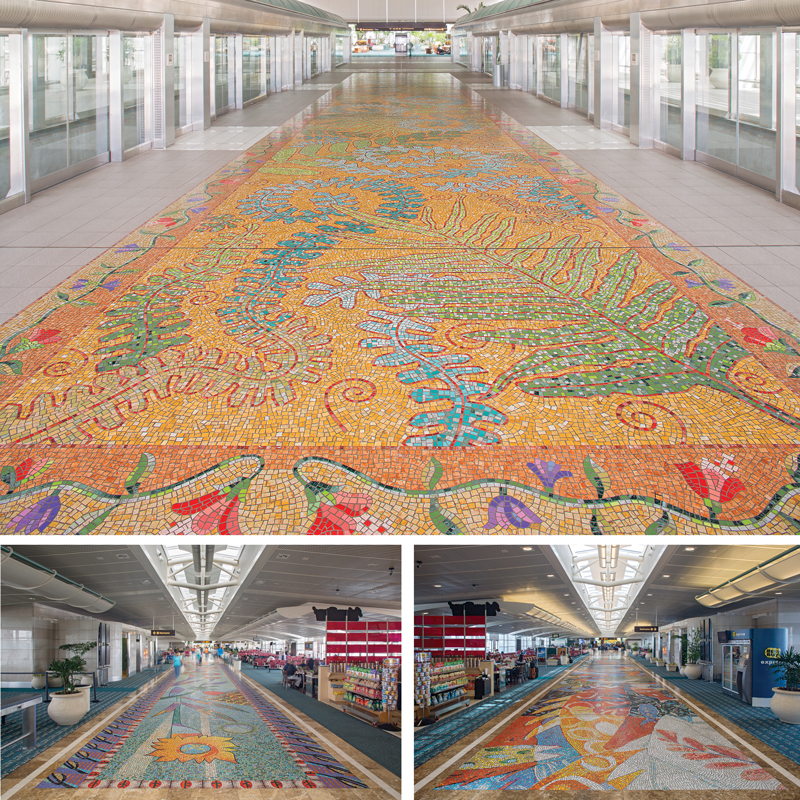

Ripples in White hangs on a wall. But Wellness Garden, installed late last year at the west end of the A-Side of the Main Terminal, is on the floor. It’s South Dakota-based artist Scott Parsons’ 28-by-32-foot homage to the region’s rich agricultural history.

Subsequent epoxy-terrazzo “welcome mats” will showcase technology, attractions and the space industry.

About half the artists whose work appears in the OIA collection are from Florida. Three, in addition to Sorensen, have Winter Park roots. All created vivid floor mosaics that have by now been admired — and trod upon — by millions.

Henry Sinn’s Field of Ferns, located in Terminal A near the tram, features a variety of stylized ferns in turquoise, green and other colors against a vivid yellow background.

Grady Kimsey’s Florascape, located in Terminal A near Gates 123 and 124, is brimming with wildflowers and sunshine. It’s a favorite with children, who can often be seen carefully traversing the stems or jumping from flower to flower, hopscotch style.

Victor Bokas’ Florida Vacation, located in Terminal A near Gate 103, is nautically themed, dominated by abstract fish. A segment of that piece was used by OIA on a collectible trading card as part of a program sponsored by the Airports Council International.

Art has been integral to OIA ever since the facility opened in 1981. And a portion of construction funding for expansions and improvements is still earmarked for art acquisition. Today, OIA’s collection is among the largest public art collections in the Southeast.

“Our art collection from ceiling to floor has been recognized locally and nationally,” says Frank Kruppenbacher, OIA’s chairman. “We’ve always said this airport is more than an airport. It’s a reflection of the experiences of Central Florida.”

Adds Fennell: “We want our art to reflect the Orlando experience. When you arrive here, we want you to know you’re in Florida just by looking at the art.”

— Randy Noles