Billy Collins is known for writing about everyday life with quirky sincerity. So, assuming “January in Florida” accurately reflects his state of mind, then the former two-term U.S. poet laureate — a much-traveled native New Yorker — seems to have adapted well to life in lush and laid-back Winter Park.

Collins — who is droll and self-deprecating — doesn’t take himself nearly as seriously as one might expect, given his stature as a literary icon. Or perhaps he does. “It’s mildly ironic,” he says. “The writer not taking himself that seriously distracts the reader from how seriously he takes himself.”

One thing, though, is certain. Even the most serious poets usually labor in obscurity, while the sometimes not-so-serious Collins churns out bestsellers and packs venues around the world.

He has been adopted by locals as their favorite resident celebrity — no offense to Carrot Top — and the most important writer to have a Winter Park address since novelist Irving Bacheller (Eben Holden: A Tale from the North Country) lived here before World War II.

Poet Robert Frost, who, like Collins, enjoyed enormous popularity during his lifetime, once said: “There is a kind of success called ‘of esteem,’ and it butters no parsnips.” Collins would undoubtedly agree.

January In Florida

The weather here does not feel

like the actual weather around me.

It seems more like the weather

someone would describe to me over the phone

while I sat in a chair by a window

as the snow piled up against the trees.

Yet here I am, barefoot on a dock,

lily pads and reeds in the foreground,

the sparkling lake beyond,

cypress and palm on the far shore,

and above it all, a soft blue empty sky.

The radio mentioned a high of 80,

but no matter how the day improves,

I will not pick up the phone

and call my friend in northern Minnesota

then listen patiently to his recent woes—

the thing with his secretary,

and the arrest of a nephew—

while I observe a pair of wading egrets

or the splashy landing of a pair of ducks.

Nor will I dangle my feet in the water

as I wait for as long as it takes

for him to get to that inescapable topic

that surely cannot be avoided much longer.

He counts among his biggest boosters people who don’t otherwise care for poetry, but are engaged by the humor and poignance that emanate from his comfortably hospitable verses. Such universal appeal is, in large part, why Collins always has plenty of butter for his parsnips.

“Billy is truly a national treasure, even an international one, and we are extraordinarily lucky he has landed with us,” says Gail Sinclair, executive director of the Winter Park Institute at Rollins College. “What a gift we’ve had, having him here.”

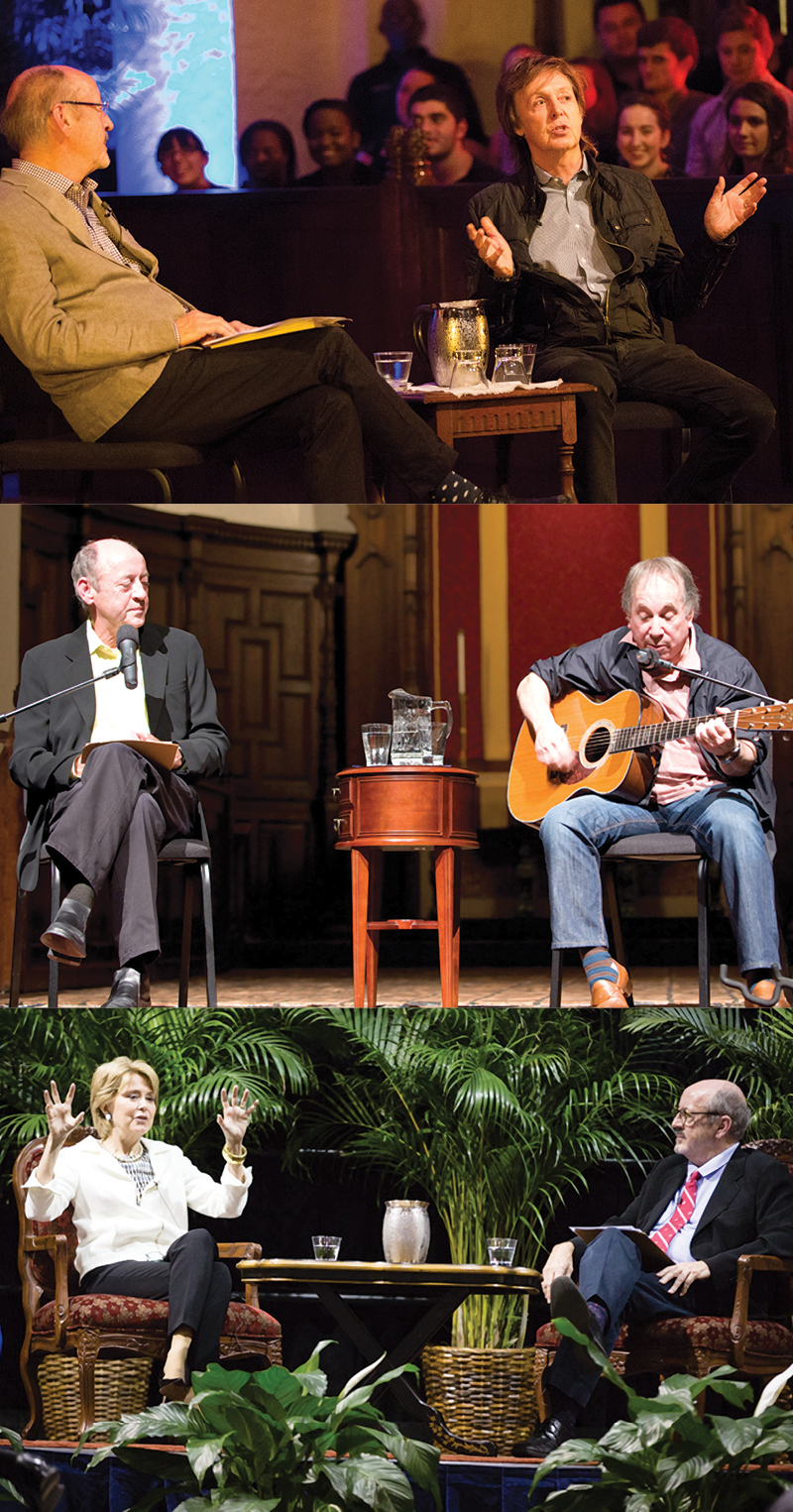

Sinclair often asks Collins, who holds the lofty title of senior distinguished fellow at the institute, “to consult his Rolodex, or whatever the electronic equivalent of that is,” and call upon friends to be part of the popular speaker series that she manages from offices in historic Osceola Lodge, once the seasonal home of Winter Park benefactor Charles Hosmer Morse.

Paul McCartney, Paul Simon and Garrison Keillor — now an unexpectedly controversial figure due to a sexual harassment allegation — have been among those who’ve happily obliged. Cartoonist Jules Feiffer, playwright Marsha Norman and TV journalist Jane Pauley also came to Winter Park at Collins’ behest.

“These days, I basically run the Billy Collins business,” says the 76-year-old poet, a wiry man with a balding pate and an on-again, off-again goatee.

Business is booming; Collins’ books — including last year’s The Rain in Portugal — typically land on the New York Times bestseller list, which is an anomaly for collections of poetry. Consequently, nearly every week finds Collins standing behind a lectern somewhere, reading his work and meeting his fans.

“I answer mail, respond speaking invitations, that sort of thing. But because I’m a writer, I make spare time in the morning to write. I sit in the same chair — sometimes with an encyclopedia — and read poems to get in the proper state of mind. Something usually results.”

Collins writes only in Fabio Ricci notebooks using Palomino Blackwing pencils — preferably the pearl edition. The lined notebook pages are filled with poems in various stages of completion, the scribbled words adorned with arrows and strikethroughs.

“I’ve never worked on a computer,” he says. “This way, I can make a mess on the page. Plus, I can leave behind a diagram of how the poem came together.”

One work in progress involves novelist Charlotte Bronte and naturalist John Muir — who share an April 21 birthday, but otherwise appear to have had little in common. That is, until now.

A POET’S PROGRESS

Collins was born in Manhattan and grew up in Queens and White Plains, New York. His father, William (Bill), worked for an insurance agency, while his mother, Katherine (Kay), was a nurse who quit her job to raise the couple’s only child.

Bill — a dapper extrovert who called his son “Champ” — brought home editions of Poetry magazine, which made an impression on the writerly youngster.

“Being a poet requires that you have a deep and sustaining interest in yourself,” says Collins, who remembers writing his first poem — it was about a sailboat he saw traversing the Hudson River — at about age 10. “So being an only child is perfect preparation for a career in poetry.”

After graduating from Archbishop Stepinac High School in White Plains, Collins attended the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, earning a B.A. in English. He then enrolled at the University of California, Riverside, earning an M.A. in English and a Ph.D. in Romantic poetry.

Collins, who had never been west of the Mississippi River, recalls driving cross-country to California in a Sunbeam Alpine convertible while reading Miss Lonelyhearts, a black comedy by Nathaniel West. He propped the book open on the steering while navigating pre-interstate two-land roads.

His first classroom post was as a teaching assistant at San Bernadino Community College. Then it was back to New York and Lehman College, part of the City University of New York (CUNY), where he taught English and composition. (Although he stopped teaching seven years ago, Collins remained affiliated with CUNY for a half-century, retiring last year as poet in residence.)

Teaching provided a steady paycheck, but Collins, from the time he was in high school, always thought of himself as first and foremost a poet. He assigned his students the task of memorizing a poem of their choosing, hoping that the work would remain with them for life.

EXPECT TO BE DELIGHTED

Collins’ first book of poetry, The Apple That Astonished Paris, was published in 1988. The collection included some of his most anthologized poems, including “Introduction to Poetry,” “Another Reason Why I Don’t Keep a Gun in the House” and “Advice to Writers.”

He also published poems in Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, The Paris Review and Poetry Magazine, refining along the way a witty and at times sentimental poetic persona that Collins refers to as his “writing self.” That self, Collins notes, is “monastic, detached, doesn’t have a job — he drinks tea and I drink coffee.”

In any case, Collins the writer has thus far produced 13 volumes of published poetry, while Collins the personality has appeared regularly on A Prairie Home Companion — the first time in 1998, after which his book sales skyrocketed — and on other NPR programs, including Fresh Air with Terry Gross. The TED Talk in which he recites two poems about the inner thoughts of dogs has garnered nearly 1.6 million views.

In some academic circles, being popular means being dismissed. Collins, though, makes no apologies for writing poetry that people from all walks of life can enjoy. Not long ago, at his annual standing-room-only public reading at Rollins, he summed up his philosophy — and revealed his worldview — when answering an audience member’s question about his approach to writing.

“Some people expect to be disappointed by life,” he said. “I expect to be delighted.” The crowd at Knowles Memorial Chapel was, well, delighted.

“If you break away from the pack and attract a broader audience, sometimes you’re derided by the very people who complain about a lack of readers for poetry,” Collins notes. “If being accessible means it’s easier to get into the poem, then I’d compare that to an accessible building. It’s easier to get into — but once you’re inside, all sorts of interesting things can happen.”

Says Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Stephen Dunn: “We seem to always know where we are in a Billy Collins poem, but not necessarily where he’s going. He doesn’t hide things from us, as I think lesser poets do. He allows us to overhear, clearly, what he himself has discovered.”

A typical Collins poem opens unambiguously enough. Take the one at the top of this story. Just don’t take it for granted. The scene may be a placid lake but, as usual, there’s something underneath the surface. In this case, it’s a contradiction — one that’s never resolved: The speaker feels both perfectly at home and somehow out of place.

Perhaps a bit like Collins himself. He’s thrilled to be in Winter Park, of course, but you get the impression that he’d sooner give up the lofty titles that have come his way than give up the 914 prefix — Westchester County, in the Hudson Valley — still on his cell phone.

AN UNANTICIPATED ELEGY

Collins was still teaching at Lehman College in 2001 when he was asked by Librarian of Congress James Billingham to serve as the country’s poet laureate. “Such a thing never occurred to me,” he says. “I didn’t think I was serious enough.”

The primary duty of a poet laureate, according to the Library of Congress, is to deliver a couple of lectures and “to raise the national consciousness to a greater appreciation of the reading and writing of poetry.”

However, most poet laureates use their bully pulpits to launch poetry-related initiatives of their own creation. For Collins, it was “Poetry 180,” for which he selected 180 poems — one for each day of the school year — to be read and discussed in high schools.

But after September 11, 2001, the largely honorary post gained unanticipated gravity. As the first anniversary of the terrorist attacks approached, Collins was asked to write a poem commemorating the victims — and to read it before a joint session of Congress held in New York City.

“I didn’t think I was up to it,” he recalls. “I said, ‘I don’t think I can. I write poems about walking the dog.’ But I promised that I would show up and read something. It was my sense of Catholic responsibility.”

Collins — in his usual gentle, comforting tone — delivered a masterful elegy called “The Names,” which alphabetically incorporated the surnames of those who had been killed. As cameras scanned the audience of lawmakers, it was clear that many were holding back tears. The poem concludes with a heart-wrenching finale:

Alphabet of names in a green field.

Names in the small tracks of birds.

Names lifted from a hat.

Or balanced on the tip of the tongue.

Names wheeled into the dim warehouse of memory.

So many names, there is barely room on the walls of the heart.

Collins, not wishing to appear exploitative, initially refused to include “The Names” in any of his books. It first appeared in The Poets Laureate Anthology, released by the Library of Congress in 2010. It was finally published in a Collins anthology when Aimless Love was released in 2013.

WHAT HE DID FOR LOVE

Winter Park wasn’t on Collins’ radar until 2002, when he did a reading at Valencia College — then Valencia Community College — and met attorney Susannah Gilman, who had previously written him a fan letter. Well, a fan email to be more precise.

In the book-signing line, when Gilman’s turn came, she reminded Collins about the correspondence. Then, much to her amazement, the poet pulled a printed copy out of his jacket pocket. At the time, both were near the end of troubled first marriages. They struck up a friendship that became a romance — at first, a long-distance one.

“I kept reminding Billy that he could live anywhere he wanted,” says Gilman, a writer of poetry, essays and fiction who blogs on a site called The Gloria Siren (a play on the name Gloria Steinem). “He had this idea of Central Florida being all about Disney. So, I took him to Winter Park and it reminded him of the villages he knew in upstate New York.”

Everything fell into place in 2008, when Collins accepted the position of senior distinguished fellow at the fledgling Winter Park Institute. His affiliation gave the institute instant credibility. And his celebrity status attracted — and still attracts — big-name guest speakers.

Collins and Gilman spend their days bicycling, reading, writing and golfing. Gilman, who no longer practices law so she can accompany Collins to his far-flung speaking engagements, admits that it isn’t easy writing poetry when you’re living with a poet laureate.

But the two critique one another’s work, and Gilman describes Collins as “tough, but very encouraging.”

When Collins isn’t writing or traveling, he enjoys the company of friends — some famous, some not. He looks forward to a longstanding annual golf getaway in Arizona with comedy writer Brian Doyle Murray, literary agent Chris Callahan and poker writer John Stravinsky, grandson of the legendary composer.

He enjoys jazz — no surprise there — but also listens to bluegrass and classic country music, favoring Hank Williams, Buck Owens and the harmonies of the Everly Brothers.

LION IN THE SUBTROPICS

Prestigious organizations are always bestowing upon Collins awards of one kind or another, which indicates that his work — appealing to novices though it may be — is held in equally high esteem by most credentialed arbiters of what’s truly worthy.

Accolades include the Mark Twain Prize for Humor in Poetry — he was the inaugural recipient — as well as fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. In 1992, he was chosen by the New York Public Library to serve as “Literary Lion.”

Last year, Collins was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters, an honor society of the country’s 250 leading architects, artists, composers and writers. Founding members included William Merritt Chase, Kenyon Cox, Daniel Chester French, Childe Hassam, Henry James, Theodore Roosevelt, Elihu Vedder and Woodrow Wilson.

More frequently these days, Winter Park settings are appearing in Collins’ work. “Cemetery Ride,” which was published in the Atlantic and later included in Aimless Love, is about a bicycle excursion through the city’s historic Palm Cemetery, during which the poet greets many of the permanent occupants by name and speculates about their lives.

My new copper-colored bicycle

is looking pretty fine under a blue sky

as I pedal along a sandy path

in the Palm Cemetery here in Florida,

wheeling past the headstones of the Lyons,

the Campbells, the Vesers, and the Davenports,

Arthur and Ethel, who outlived him by eleven years

I slow down even more to notice,

but not so much as to fall sideways on the ground.

And here’s a guy named Happy Grant

next to his wife Jean in their endless bed.

Annie Sue Simms is right there and sounds

a lot more fun than Theodosia S. Hawley.

And good afternoon, Emily Polasek,

and to you too, George and Jane Cooper,

facing each other in profile, two sides of a coin.

I wish I could take you all for a ride

in my wire basket on this glorious April day,

not a thing as simple as your name, Bill Smith,

even trickier than Clarence Augustus Coddington.

Then how about just you, Bernice Owens?

Would you gather up your voluminous skirts

then ride sidesaddle on the crossbar

and tell me what happened between 1863 and 1931?

I’ll even let you ring the silver bell.

But if you’re not ready, I can always ask

Amanda Collier to rise from her long sleep

beneath the swaying gray beards of Spanish moss

and ride with me along these sandy paths

so I can listen to her strange laughter

as some crows flap in the blue overhead

and the spokes of my wheels catch the dazzling sun.

Gilman agrees that Collins has public and private personalities. The private version, she insists, is even more endearing than the charmingly rumpled figure who disarms audiences with his wit and warmth.

“When I go to Billy’s readings, I’m never nervous for him,” she says. “He’s a pro. He can read the audience. And after it’s over, I can say, ‘I get to go home with that guy.’”

“Home,” in this case, being Winter Park.

Lucky for her. Lucky for us.

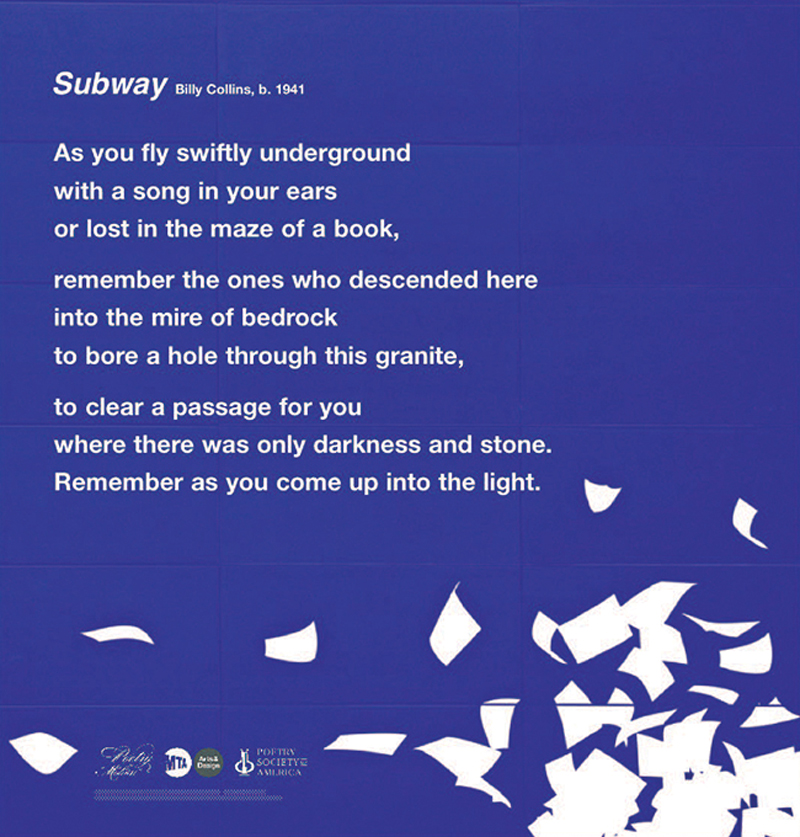

UNDERGROUND POET

A New Yorker to the core, Billy Collins is especially quite proud of a poem that will never make it into one of his books: Called “Subway,” it was commissioned by the Metropolitan Transit Authority though its “Poetry in Motion” program to mark the opening of the new Second Avenue subway line on the Upper East Side.

The poem — an ode to the workers who labored to build the city’s mind-boggling subway system — was reproduced on a commemorative poster designed by graphic artist Sarah Sze.

If you’re lucky, you might’ve gotten a signed poster from Collins himself — who’s a past New York State poet laureate. Earlier this year, he was in the Big Apple distributing them out to surprised commuters.

Otherwise, you can find the bright blue posters decorating subway cars throughout the busiest underground transit system in the Western Hemisphere.

“We invited Billy Collins to write a poem since his way with words speaks to all New Yorkers, with a purity of thought that gets to the meaning in a way we all understand,” says Sandra Bloodworth, director of MTA Arts & Design, which runs the Poetry in Motion program. “And he does it with a lyrical brilliance.”