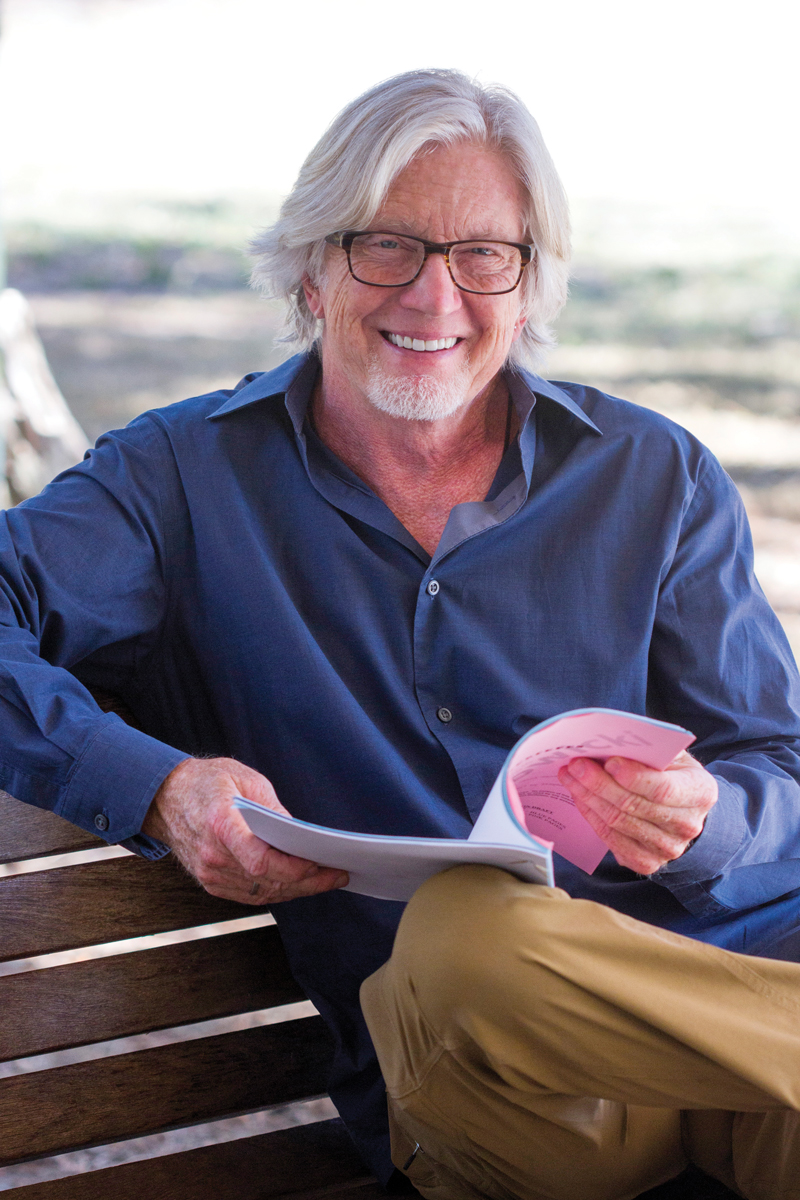

Actor Tom Nowicki is often recognized. Sometimes, he’s recognized as Kris Kristofferson, with whom he appeared in 2011’s Dolphin Tale, a hit family drama that also starred Harry Connick Jr., Ashley Judd and Morgan Freeman.

Nowicki and Kristofferson bear a passing resemblance to one another, particularly when Nowicki’s reddish hair — lightened to white from exposure to swimming-pool chlorine — is worn shoulder-length.

But more often these days he’s recognized as himself, from featured roles in dozens of films and television programs spanning a career that’s approaching the 40-year mark. “Hey, look,” says a woman at sipping a latte at the Park Avenue Starbucks. “That’s Tom, the actor.”

More precisely, that’s Tom, our actor.

Amanda Bearse (Married with Children), Davis Gaines (Phantom of the Opera) and Billy Gardell (Mike and Molly) — all of whom boast deep Winter Park roots — are more widely known. But none is as prolific. And only Nowicki has continued living locally — despite professional pressure to move someplace else.

Nowicki admits that having a New York or a Los Angeles address would be advantageous in his line of work. But perhaps not as advantageous as it once was.

Most films these days are made in Canada, Georgia, North Carolina and other places where, unlike Florida, filmmakers are offered significant incentives. He’d be racking up frequent-flyer miles regardless.

“It’s great to be able to work and then come back to a place I can call home,” says Nowicki, 61, whose family moved to Winter Park from Detroit in 1968. “It’s so easy to live here. It’s friendly and accessible and green.”

Then he adds, only partially in jest: “Lake Baldwin Park is great; maybe that’s really the reason I stay here.” The park is a 23-acre waterfront expanse, 11 acres of which are dedicated to off-leash dogs.

‘I KNOW THAT FACE’

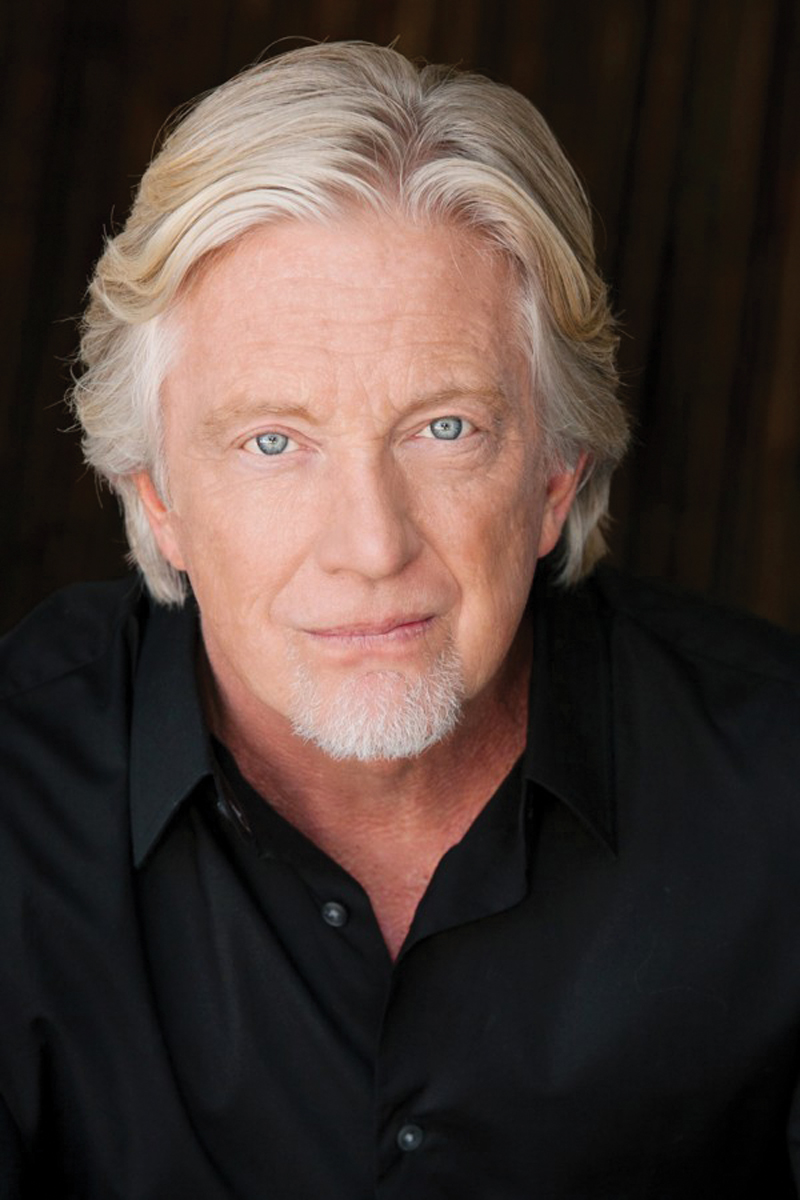

Nowicki has been in so many television programs — more than 100 credits and counting — that a dedicated couch surfer might see him portraying a hapless prosecutor on rerun of Matlock, and then, with the click of a button, see him again, this time portraying a Russian spy on a rerun of Burn Notice.

He’s also been in at least 50 feature films, covering an array of genres — comedy, drama, action, science fiction and horror. But perhaps his most high-profile role in recent years was in the biographical sports drama The Blind Side (2009), starring Sandra Bullock, who won an Academy Award for her role as Leigh Ann Tohey.

Tohey, you’ll recall, is a successful interior designer who becomes the adoptive mother of a promising football prospect, Michael Oher (Quinten Aaron).

Nowicki portrays the uncompromising literature teacher whose class Oher must pass to become eligible for a college scholarship. Later that year, the character was later parodied by Seth Myers during the 2009 ESPY (Excellence in Sports Performance) Awards, broadcast on ABC. Oher was played by Peyton Manning.

“That was quite a moment, seeing your role become part of a comedy skit,” says Nowicki. “Seth was great, but they could have called me and had the real guy.” (Spoiler alert: Oher goes on to become an All-American at Old Miss, and plays for eight seasons in the NFL.)

But for every Blind Side-style blockbuster — which Nowicki says pays the bills — there’ve been meatier roles in edgy independent productions, stints on network and cable television programs and even stretches as a pro wrestling heel and a caddish roller-derby mogul.

More recently, Nowicki landed a recurring role on Manhunt: Unabomber, a Discovery Channel miniseries in which he portrayed dogged FBI agent Tom McDaniel, who tracked Ted Kaczynski into the Montana wilderness.

He now has a recurring role in Mr. Mercedes, a television adaptation of Stephen King’s hard-boiled detective novel of the same name. The show airs on Audience TV, a streaming service available through AT&T U-verse or DirecTV.

Coming up, Nowicki will portray a French mesmerist in The Path, a Hulu original series, and has several theatrical films and a new TV series — Lodge 49, produced by Academy Award-nominated actor Paul Giamatti — in post-production.

Nowicki has done voiceover work, produced several art-house films and appeared in countless plays, tackling roles that range from Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire to a gay concentration-camp prisoner in Martin Sherman’s Bent.

Once a regional theater regular, Nowicki is more selective about his stage work these days. The money isn’t very good, for starters. And it can be tough to sell an agent on the idea of a long-term theater commitment if a much more lucrative gig in a film or a television program might be just around the corner.

Still, Nowicki says the gig he enjoyed the most was at the American Stage Theater Company in St. Petersburg. He portrayed the mysterious Mr. Lockhart — actually, the devil himself — in a 2010 production of The Seafarer, playwright Conor McPherson’s dark and drunken Christmas-themed comedy.

“I was asked to do the show, and at first thought I was a terrible choice for the role,” he recalls. “But it all came together in a magical way. It was eight shows a week in a three-week run — and I never got tired of going to work. That’s the best gauge I can give you for how much I enjoyed it.”

A true actor’s actor whom casting directors know will wring the most from any role he tackles, Nowicki has never wanted for steady work. He typically stays busy at least 30 weeks a year, and — despite the usual ups and downs — has never experienced a truly alarming dry spell.

Major star stature has seemed tantalizingly within reach several times. For example, in 2000 Nowicki beat out Corbin Bernsen (L.A. Law, Psych) for a leading role in L.A. Confidential, a television pilot based on the Academy Award-winning 1997 film.

The pilot starred Kiefer Sutherland, who at 24 was already an established film star. It was praised by Entertainment Weekly as “the show to watch” for the coming season. “I felt like that was where my entire career was leading,” Nowicki recalls. “I thought it was my time and my moment.”

However, the networks — perhaps daunted by the expense of shooting a series set in 1950s Los Angeles — passed on the project. Sutherland went on the following spring to star in the Fox espionage thriller 24. Nowicki, who had figured L.A. Confidential would run for five or six seasons — went back to Winter Park.

He was discouraged — as all actors have been — but undaunted. He continued to audition, and to approach every role offered to him with undiminished seriousness and professionalism.

DERFLINGER’S DISCIPLE

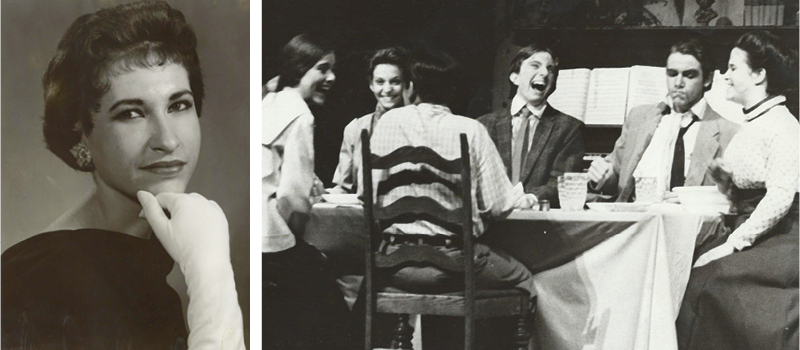

Nowicki’s prodigious work ethic was the result of training by Ann Derflinger, the legendary drama teacher at Winter Park High School who inspired him, encouraged him — and terrified him.

The formidable Derflinger, who died of cancer in 1984 — and for whom the school’s auditorium is today named — influenced hundreds of Winter Park High School graduates, whether they pursued acting as a career or not.

“I was scared of her at first,” recalls Nowicki of the 5-foot-tall dynamo who exerted — and still exerts — an outsized influence in his life. “I think I’d be a little scared of her now. She believed in the theater. When you got praise from her — which was rare — it was exhilarating. It was as though she, and she alone, spoke for the theater gods. Her approval meant everything.”

Derflinger, who had graduated from Rollins College and enjoyed a brief career as a stage actress before deciding to teach, was a meticulously stylish woman known to favor strong perfume. That scent, plus the rapid-fire clip-clop of her high heels, warned backstage slackers of her approach.

“I can even still smell her,” says Nowicki, who adds that Derflinger’s insistence that nothing less than 100 percent commitment was acceptable — even in high school productions — continues to guide him. “She knew how much it meant. That’s stayed with me.”

Nowicki, who keeps Derflinger’s professional head shot by his bed, counts his best-actor “Derfie” award — which was given annually at the school for outstanding achievement in student plays — among his most cherished possessions.

His first Winter Park High School role was as Reverend Hale in a 1972 production of The Crucible. He had never acted before — his career goal was to be a doctor — and had only auditioned because doing so, he was told, would earn him an extra credit in his literature class.

“The experience was an utter shock,” Nowicki recalls. “Standing in the wings, waiting to go, was electric and relaxing at the same time. I knew I’d found what I had to do for the rest of my life.” His lead role as Richard, the errant son in Eugene O’Neil’s Ah! Wilderness, earned him his coveted Derfie.

Derflinger, who was also known to idolize actor Paul Newman, encouraged Nowicki to study drama at Yale University, at least in part because Newman had studied there.

What Derflinger apparently didn’t realize — nor did Nowicki, until he arrived in New Haven as a freshman — was that Yale had recently dropped its undergraduate theater program. There were student productions — Nowicki directed two of them — and the chance to audit classes at the renowned Yale School of Drama. But that was exclusively a graduate program.

“So, I found myself in the classics department, studying in Greek,” Nowicki says. “The classes were tiny, and the faculty members were ridiculously brilliant. I’d learn as more having dinner at their homes than I’s learn in a classroom.”

CLANDESTINE CRITIC

But Nowicki was frustrated by the lack of an undergraduate theater program. So, in 1977 he took a year off and returned to Winter Park, where he began appearing in plays at Rollins, which sometimes used non-student actors in its productions.

There, he fell under the influence of another memorable character, theater director Robert Jurgens, who cast him The Runner Stumbles, The Norman Conquest and One Flew Over the Cookoo’s Nest at the Annie Russell Theater.

“Dr. Jurgens was really cunning about his process,” says Nowicki. “He pretended to be this gruff, no-navel-gazing kind of guy. But his work was as deep as anybody’s. And he taught young, self-absorbed actors a critical lesson: The real craft of acting, along with honesty and passion, is being loud and clear enough that the audience can recognize all the clever things you’re doing.”

Nowicki graduated from Yale in 1978 with a degree in English literature — Greek had simply become too difficult, he says — then was off to London, where he studied Shakespearean and classical acting at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art.

“I loved London so much that I begged every female classmate to marry me, so I could get a visa and stay,” Nowicki says. “But despite what you might hear about British schoolgirls, they’re not easily fooled.” He returned to Winter Park to plot his next move.

While appearing in local plays, he began a just-for-fun stint as theater critic for the Winter Park Outlook, a weekly newspaper. He wrote under a pseudonym, Rupert Birkin, and his reviews were incisive and, to some in the local theater community, insufferable.

For example, Birkin was banned from Once Upon a Stage Dinner Theater in College Park after he penned a review comparing the flag-waving patriotism of 1776, the theater’s current offering, to “a Marxist pageant.” The long-defunct venue’s owner told the newspaper’s editor that Birkin was “a pompous jerk.”

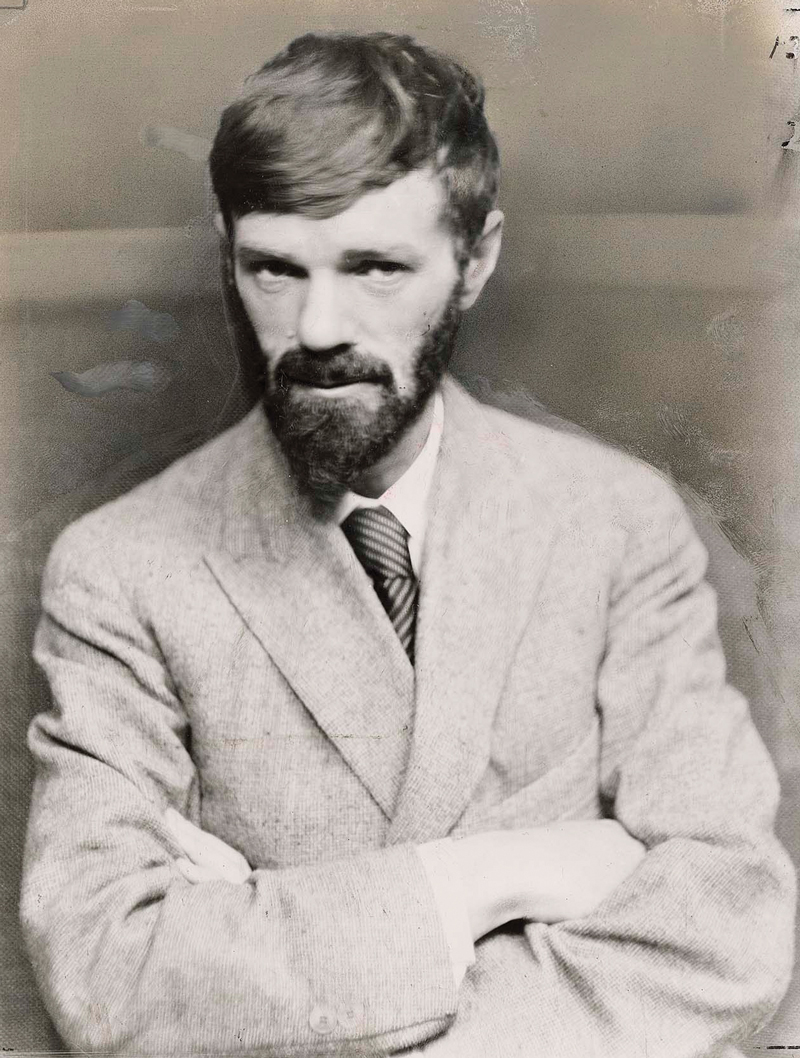

Birkin is, in fact, a character in D.H. Lawrence’s 1920 novel Women in Love. Nowicki even selected a drawing of Lawrence to accompany his column, assuming that some savvy reader would make the connection. None did — and the wickedly witty Birkin became a minor local celebrity before mysteriously resigning his post at what he termed “the drama desk.”

“I knew I couldn’t write under my own name,” says Nowicki. “I was acting with some of these people around town, and anything I had to say, good or bad, would make things tricky. It was a good choice, as it happened, since I discovered that I had a fairly profound mean streak — at least while posing as a critic.”

Still, Nowicki adds, it was interesting to write character as Birkin, whom he describes as “this overwrought, braying jackass who spared no one. And I did try to even things up with the loftiest praise, where it was deserved — although I may have failed in that regard.”

Nowicki then began auditioning for plays statewide. There were, at the time, 30 professional theaters “that paid enough for a 24-year-old.” He got his Actors’ Equity card in 1980, which he marks as the beginning of his professional career.

Nowicki’s first film role was in 1984’s Harry & Son, which starred Paul Newman and Robbie Benson. The film was directed by Newman, whom Nowicki remembers as gracious and surprisingly tolerant of the nervous rookie who accidentally backed a Corvette into a bank of lights. Recalls Nowicki: “I was sure I was going to be whipped or fired — or both.”

In fact, Nowicki became friendly with Newman, and told him about Derflinger, who was by now gravely ill: “Paul said, ‘Tom, have got a script?’ I got my script and took it to his trailer. On it he wrote a long, personal note to Miss Derflinger, thanking her for the work she’d done inspiring young actors. He even signed a photograph — something he almost never did — and me to give it to her.”

Back in Winter Park, Nowicki presented the script and picture to Derflinger, who was hospitalized. “That was the first time I’d ever seen her not entirely poised,” he says. Derflinger died just months later, at just 44, and was buried in Winter Park’s Palm Cemetery.

DIALOGUE AND DROP-KICKS

Nowicki’s early career was a heady time, when some community leaders were touting Orlando as “Hollywood East.” A handful of films were shot here — none of them very distinguished — and Nowicki was in most of them: from Ernest Saves Christmas (1988) with Jim Varney to The Waterboy (1998) with Adam Sandler. His role in Parenthood, the 1989 family comedy starring Steve Martin, didn’t make the final cut.

But Nowicki’s most interesting work, at the time, wasn’t in television or film: it was in the “squared circle,” as the late Gordon Solie, the dean of professional wrestling announcers, described the enclosure in which musclebound behemoths enact carefully scripted — but often bloody — matches that featured body slams, arm locks, drop kicks, sleeper holds and figure-four leglocks.

In 1987, Nowicki noticed a classified ad for a “wrestling school.” He was intrigued — it was not then widely known just how choreographed professional wrestling was — and enrolled. After all, wrestling was nothing if not theatrical.

The game 165-pound actor was taught the tricks of the trade by Rocky Montana, a grizzled heel (villain, in wrestling parlance) whose small-time Dixie Wrestling Alliance staged matches in local armories and high school gyms. The seemingly mismatched pair became close, and Nowicki was welcomed into the carny culture that wrestling exemplifies.

“I just thought [wrestling] would be fun to go and do, and write about,” says Nowicki, who at the time contributed freelance stories about topics that interested him to local magazines. “And it was.”

The tale of Nowicki’s association with the Dixie Wrestling Alliance became a hilarious — and at times poignant — magazine piece that described his rough-and-tumble training regimen.

But it also sympathetically explored the sometimes-desperate dreams of grappling glory harbored by about a dozen other students, all of whom grew up idolizing the likes of Dusty Rhodes and Rick Flair.

The piece, which ran in the Orlando Sentinel’s Sunday magazine section, described the reaction Nowicki received when he announced his intention to pursue wrestling:

“When I confided this new inspiration to family and friends, the response was a near-unanimous sneer. One or two worried about my health, primarily physical. Only my mother was unconcerned: She understood me to say I was going to ‘resting’ school, which she thought redundant in my case, but at least indicated I wanted to do something well.”

He did do well, although not as a wrestler. He obviously didn’t have the size to credibly match up against a would-be Hulk Hogan. But his acting chops served him well as a manager — the character who ostensibly guides the careers of other wrestlers, usually heels, and routinely interferes in their matches.

And so it was that the pompous “Lord Larry Oliver” became a fixture at Dixie Wrestling Alliance matches, shouting insults at jeering crowds — using a condescending British accent, of course — and employing foreign objects to gore the opponents of his evil minions.

Nowicki quickly recognized that wrestling could appeal to playgoers with a sense of humor. He persuaded Montana to stage a program of matches at Theater Downtown, an Orlando performance venue frequented by arts-loving hipsters.

A full house enjoyed the no-holds-barred evening, which presaged by a decade the wholesale melding of wrestling and show business by Vince MacMahon Jr. and the World Wrestling Federation.

Sadly — or perhaps fortunately, at least for him — Nowicki’s wrestling career was ended by injuries he sustained during a Battle Royale, in which a cadre of wrestlers attempt to toss one another over the top rope. The last man standing is declared the winner — but that man was not Lord Larry Oliver, who suffered several broken ribs as the result of a hard fall.

Later, from 1999 to 2001, Nowicki’s wrestling background informed his portrayal of the disreputable Kenneth Loge III on Spike TV’s RollerJam, a glitzy revival of the down-and-dirty roller derby programs that were popular in the 1950s.

The self-righteous Loge — billed as “the most hated man in sports” — was “commissioner” of the World Skating League, and one of three triplets fighting for control of the league. Nowicki also played brothers Benny and Lenny as well as their mother, Drucilla. The show, which borrowed many familiar wrestling tropes, was filmed at Universal Studios Florida.

Even Sen. John McCain wanted in on the fun. During the 2000 presidential primaries, McCain’s campaign contacted producers to ask if Loge would appear alongside the eventual GOP nominee at a rally in Florida. Why anyone believed that this pairing would bolster McCain’s chances remains a mystery.

“We told them that [Loge] had already endorsed Pat Buchanan,” says Nowicki, who figured that the irascible right-wing windbag would be precisely the sort of character that the overbearing roller derby mogul would have supported for the presidency.

AN ACTOR’S ACTOR

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Nowicki had recurring roles in The New Leave it to Beaver, Superboy and Swamp Thing, all of which were shot in Orlando. He later played a Russian astronaut in The Cape, a series filmed in and around Cape Canaveral in Brevard County.

There was also a slew of made-for-television movies, and longish stints on NBC’s Matlock and the USA Network’s Necessary Roughness.

Nowicki’s big-budget theatrical credits included Remember the Titans (2000), a feel-good football flick starring Denzel Washington, and The Punisher (2004), a vigilante action thriller based on the Marvel Comics character of the same name.

In The Punisher, Nowicki played a machine-gun toting bad guy who gets his comeuppance. In fact, his character’s brutal onscreen slaying was ranked by Fangora magazine as among the “Top 10 Deaths in Film History.”

Since then, it’s been an unbroken string of indie movies and television appearances. In fact, between his recent projects and reruns, Nowicki has become almost ubiquitous on television.

“There aren’t too many actors in Florida who can say they make a living doing nothing other than acting,” says Traci Danielle, president of Orlando-based Brevard Talent Group, one of the agencies that represents Nowicki.

“I like to work with actors who have that chameleon-like quality, and Tom does,” adds Danielle, whose roster includes about 75 clients. “He can play anything. He’s part of my A-team — which means he can consistently close the deal.”

Nowicki’s New York agent, Justin Busch of Clear Talent Group, agrees: “Tom is a really transformative character actor,” Busch says. “He can play an upscale CEO, or a blue-collar, down-on-his-luck guy. Not everyone can pull off that dichotomy.”

It’s Nowicki’s personal qualities make him an even better actor, Danielle says: “Tom’s such a great human being. He’s so humble, and he has real empathy. He’s the type of guy who, if he had just had a dollar, would give it to somebody else who he thought needed it more.”

Or, he might use it to help aging or injured animals. In 2001 Nowicki co-founded — with his friend, Winter Park resident Kristina Lake Latimer — a business called Hip Dog Canine Hydrotherapy & Fitness, which offers swim therapy for dogs that have mobility issues as a result of conditions such as arthritis and amputation.

In 2011, the pair turned the operation — which did too much pro bono work to ever be profitable — over to Beverly and Peter McCartt, who expanded its services to include conditioning and weight-loss programs for dogs.

“I found out I was the world’s worst businessman,” says Nowicki, who still swims with the company’s furry clients when he’s in town. “Beverly and Peter have done so much more with it; they’ve turned it from something aspirational to something truly real.”

When Nowicki isn’t traveling, he can usually be found at Lake Baldwin Park accompanied by Dexter, his one-eyed springer spaniel. “Having dogs has changed my life in profound ways,” says Nowicki, who adopted his first dog, a sainted Labrador retriever mix whom he named Shea, in 1994.

Shea, in fact, provided the impetus for Nowicki — and like-minded locals with dogs who liked to romp — to successfully lobby the city for creation of an off-leash park in the little-used tract then known as Fleet Peeples Park. They formed a nonprofit, now known the Friends of Lake Baldwin Park, to protect and enhance the wooded waterfront space.

In Shea’s day, dogs weren’t welcomed on most sets. Now, though, Nowicki is able to take Dexter with him on some dog-friendly shoots.

What does the future hold for Winter Park’s most visible resident actor? All Nowicki can say for certain is that he’ll continue to perform.

“I’ve never had another serious job, besides acting,” he notes. “And I’ve never wavered or had any thought of finding something else to do. I’m at the stage of my career where I still have a chance to be a big dog — and if not, at least I can provide support to a different big dog.”